- Watts Riots

-

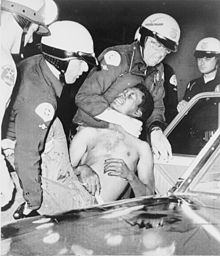

The term Watts Riots of 1965 refers to a large-scale civil disturbance which lasted 5 days in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, in August 1965. By the time the riot subsided, 34 people had been killed, 1,032 injured, and 3,438 arrested. It was the most severe riot in the city's history until the Los Angeles riots of 1992.

Contents

Background

The riots began on August 11, 1965, in Watts, a neighborhood in Los Angeles, when Lee Minikus, a California Highway Patrol motorcycle officer, pulled over African American Marquette Frye on suspicion of driving while intoxicated. Minikus was convinced Frye was under the influence and radioed for his car to be impounded. Frye and Minikus had an altercation over the impound and events escalated. A crowd of onlookers steadily grew from dozens to hundreds.[1]

In response to the altercation and what was considered to be racially targeted force on the part of Minikus, the mob became violent, throwing rocks and other objects while shouting at the police officers. A struggle ensued shortly resulting in the arrest of Marquette and Ronald Frye, as well as their mother.

Though the riots began in August, there had previously been a buildup of racial tension in the area.

Looting

Watts suffered from various forms and degrees of damage from the residents' looting and vandalism that seriously threatened the security of the city. Some participants chose to intensify the level of violence by starting physical fights with police, blocking the firemen of the Los Angeles Fire Department from their safety duties, or even beating white motorists. Others joined the riot by breaking into stores, stealing whatever they could, and some setting the stores on fire.[2]

LAPD Police Chief William Parker also fueled the radicalized tension that already threatened to combust, by publicly labeling the people he saw involved in the riots as "monkeys in the zoo".[2] Overall, an estimated $40 million in damage was caused as almost 1,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed. Most of the physical damage was confined to white-owned businesses that were said to have caused resentment in the neighborhood due to perceived unfairness. Homes were not attacked, although some caught fire due to proximity to other fires.[citation needed]

Day-by-day breakdown

Wednesday, August 11

- A Caucasian California highway patrolman, Lee Minikus, arrested Marquette Frye at around 7 p.m. after Frye failed his sobriety tests.

- By 7:23 all three Fryes—Marquette, his brother Ronald, and their mother—had been arrested as a crowd of a couple hundred gathered around the scene.

- The police withdrew by 7:40, leaving behind an angered, tense crowd.

- For the last 4 hours of the night, the mob stoned cars and threatened police in the area.

Thursday, August 12

- Black leaders such as preachers, teachers, and businessmen tried to restore order in the community after a night of rampage, telling people to stay indoors.

- Around 10 a.m. community workers and officers called residents in the area, telling them to remain in their houses.

- At 2 p.m. a community meeting was held, at which members representing different neighborhood groups discussed solutions to the problem at hand; the meeting failed.

Friday, August 13

- At 8 a.m. rioting grew.

Saturday, August 14

- By 1 a.m. there were around 100 fire brigades in the areas, trying to put out fires started by rioters.

- Over 3,000 national guardsmen had joined the police by this time in trying to maintain order on the streets.

- By midnight there were around 13,900 guardsmen in the area.

Sunday, August 15

- The riots died down, leaving around $40 million in property damage.

- Churches, community groups, and government agencies gave out aid.

- The vandalism ceased and the curfew was lifted by Tuesday, August 17

- By the following Sunday, a week later, less than 300 national guardsmen remained to help out with the aftermath.

Businesses & Private Buildings Public Buildings Total Damaged/burned: 258 Damaged/burned: 14 Total:272 Looted: 192 Total:192 Both damaged/burned & looted: 288 Total:288 Destroyed: 267 Destroyed: 1 Total:268 Total: 977 Government intervention

Eventually, the California National Guard was called to active duty to assist in controlling the rioting. On Friday night, a battalion of the 160th Infantry and the 1st Reconnaissance Squadron of the 18th Armored Cavalry were sent into the riot area (about 2,000 men). Two days later, the remainder of the 40th Armored Division was sent into the riot zone. A day after that, units from northern California arrived (a total of around 15,000 troops). These National Guardsmen put a cordon around a vast region of South Central Los Angeles, and the rioting was largely over by Sunday.

Due to the seriousness of the riots, martial law had been declared. Sergeant Ben Dunn said "The streets of Watts resembled an all-out war zone in some far-off foreign country, it bore no resemblance to the United States of America". The initial commander of National Guard troops was Colonel Bud Taylor, then a motorcycle patrolman with the Los Angeles Police Department, who in effect became superior to Chief of Police Parker. National Guard units from Northern California were also called in, including Major General Clarence H. Pease, former commanding general of the National Guard's 40th Infantry Division.

Post-riot commentary

As this area was known to be under much racial and social tension, debates have surfaced over what really happened in Watts. Reactions and reasoning about the Watts incident greatly vary because those affected by and participating in the chaos that followed the original arrest were from a diverse crowd. The government tried to help by releasing The McCone Report, claiming that it was a detailed study of the riot, but it turned out to be a short summary with just 15 pages of the report devoted to actually describing the whole event.[3]

More opinions and explanations then appeared as other sources attempted to explain the causes as well. Public opinion polls have shown that around the same percentage of people believed that the riots were linked to Communist groups as those that blame social problems like unemployment and prejudice as the cause.[4] Those opinions concerning racism and discrimination emerged only three years after hearings conducted by a committee of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights took place in Los Angeles to assess the condition of relations between the police force and minorities. The purpose of these hearings was also to make a ruling on the discrimination case against the police for their mistreatment of Black Muslims.[5] These different arguments and opinions still continue to promote these debates over the underlying cause of Watts Riots.[2] Martin Luther King Jr. spoke two days after the riots happened in Watts.

A California gubernatorial commission (under Gov. Pat Brown) investigated the riots, identifying the causes as high unemployment, poor schools, and other inferior living conditions. Subsequently, the government made little effort to address the problems or repair damages. The riots were also a response to Proposition 14, a constitutional amendment sponsored by the California Real Estate Association that had in effect repealed the Rumford Fair Housing Act.[6]

Cultural references

- The film Menace ll society features the riots.

- The film There Goes My Baby features the riots.

- The novel The New Centurions, by Joseph Wambaugh, not only culminates in the Watts Riot but examines the negative impact of racist police in minority communities in the years preceding it.

- Frank Zappa wrote a lyrical commentary inspired by the Watts Riots, entitled "Trouble Every Day", containing such lines as "Wednesday I watched the riot / Seen the cops out on the street / Watched 'em throwin' rocks and stuff /And chokin' in the heat". The song was originally released on his debut album Freak Out! (with the original Mothers of Invention), and later slightly rewritten as "More Trouble Every Day", available on Roxy and Elsewhere and The Best Band You Never Heard In Your Life.

- The 1990 film Heat Wave depicts the Watts Riots from the perspective of journalist Bob Richardson as a resident of Watts and a reporter of the riots for the LA Times.

- The producers of the "Planet of the Apes" franchise stated that the riots were the inspiration for the ape uprising in the film "Conquest of the Planet of the Apes"[7]

See also

- 1992 Los Angeles riots

- Rodney King

- Billy G. Mills (born 1929), Los Angeles City Councilman, 1963–74, investigated Watts Riots

- Urban riots

- Watts Prophets

- Wattstax

- Zoot Suit Riots

Further reading

- Cohen, Jerry and William S. Murphy, Burn, Baby, Burn! The Los Angeles Race Riot, August 1965, New York: Dutton, 1966.

- Conot, Robert, Rivers of Blood, Years of Darkness, New York: Bantam, 1967.

- Guy Debord, Decline and Fall of the Spectacle-Commodity Economy, 1965. A situationist interpretation of the riots

- Horne, Gerald, Fire This Time: The Watts Uprising and the 1960s, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995.

- Thomas Pynchon, "A Journey into the Mind of Watts", 1966. full text

- Violence in the City—An End or a Beginning?, A Report by the Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots, 1965, John McCone, Chairman, Warren M. Christopher, Vice Chairman. Official Report online\

- David O' Sears The politics of violence: The new urban Blacks and the Watts riot

- Clayton D. Clingan Watts Riots

- Paul Bullock Watts: The Aftermath New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1969

- Johny Otis Listen to the Lambs. New York: W.W. Norton and Co.. 1968

Footnotes

- ^ 1 Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Race, Space, and Riots in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ^ a b c Oberschall, Anthony. "The Los Angeles Riot of August 1965" Social Problems 15.3 (1968): 322–341.

- ^ Jeffries,Vincent & Ransford, H. Edward. "Interracial Social Contact and Middle-Class White Reaction to the Watts Riot". Social Problems 16.3 (1969): 312–324.

- ^ Jeffries,Vincent & Ransford, H. Edward. "Interracial Social Contact and Middle-Class White Reaction to the Watts Riot". Social Problems 16.3 (1969): 312–324.

- ^ Jeffries,Vincent & Ransford, H. Edward. "Interracial Social Contact and Middle-Class White Reaction to the Watts Riot". Social Problems 16.3 (1969): 312–324.

- ^ Tracy Domingo, Miracle at Malibu Materialized, Graphic, November 14, 2002

- ^ Abramovich, Alex (2001-07-20). "The Apes of Wrath - By Alex Abramovich - Slate Magazine". Slate.com. http://www.slate.com/id/112241/. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

References

- Division of Fair Employment Practices, California Department of Industrial Relations (1966). Negroes and Mexican Americans in South and East Los Angeles. San Francisco: State of California, Division of Fair Employment Practices. p. 2.

External links

- http://www.usc.edu/libraries/archives/la/watts.html

- http://www.usc.edu/libraries/archives/cityinstress/

- http://www.pbs.org/hueypnewton/times/times_watts.html

- http://www.lasell.edu/images/userImages/fweil/Page_495/watts_riot.pdf[dead link]

- http://www.usc.edu/libraries/archives/cityinstress/mccone/

- http://detroits-great-rebellion.com/Watts---1965.html

Categories:- 1965 in the United States

- History of California

- History of Los Angeles, California

- 1965 riots

- Crime in Los Angeles, California

- African American riots in the United States

- Civil rights movement during the Lyndon B. Johnson Administration

- Urban decay in the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.