- David (Donatello)

-

- This article is about the sculptures by Donatello, for other uses see David (disambiguation).

David is the name of two statues by Italian early Renaissance sculptor Donatello.

Contents

The biblical text

The story of David and Goliath comes from 1 Samuel 17. The Israelites are fighting the Philistines, whose best warrior - Goliath - repeatedly offers to meet the Israelites' best warrior in man-to-man combat to decide the whole battle. None of the trained Israelite soldiers is brave enough to fight the giant Goliath, until David - a shepherd boy who is too young to be a soldier - accepts the challenge. Saul, the Israelite leader, offers David armor and weapons, but the boy is untrained and refuses them. Instead, he goes out with his slingshot, and confronts the enemy. He hits Goliath in the head with a stone, knocking the giant down, and then grabs Goliath's sword and cuts off his head. The Philistines honorably retired as pacted and the Israelites are saved. David's special strength comes from God, and the story illustrates the triumph of good over evil.[1]

The marble David

Donatello was first commissioned to carve a statue of David in 1408. The commission came from the operai of the cathedral of Florence, who intended to decorate the buttresses of the tribunes of the cathedral with 12 statues of prophets. Nanni di Banco was commissioned to carve a marble statue of Isaiah, at the same scale, in the same year. One of the statues was lifted into place in 1409, but was found to be too small to be easily visible from the ground and was taken down; both statues then languished in the workshop of the opera for several years.[2] In 1416 the Signoria of Florence commanded that the David be sent to their palazzo; evidently the young David was seen as an effective political symbol, as well as a religious hero. Donatello was asked to make some adjustments to the statue (perhaps to make him look less like a prophet), and a pedestal with an inscription was made for it: PRO PATRIA FORTITER DIMICANTIBUS ETIAM ADVERSUS TERRIBILISSIMOS HOSTES DII PRAESTANT AUXILIUM (To those who fight bravely for the fatherland the gods lend aid even against the most terrible foes).[3]

The marble David is Donatello's earliest known important commission, and it is a work closely tied to tradition, giving few signs of the innovative approach to representation that the artist would develop as he matured. Although the positioning of the legs hints at a classical contrapposto, the figure stands in an elegant Gothic sway that surely derives from Ghiberti. The face is curiously blank (curiously, that is, if one expects naturalism, but very typical of the Gothic style), and David seems almost unaware of the head of his vanquished foe that rests between his feet. Some scholars have seen an element of personality - a kind of cockiness - suggested by the twist of the torso and the akimbo placement of the left arm,[4] but overall the effect of the figure is rather bland.

The bronze David

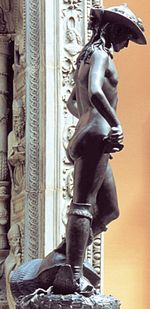

Donatello's bronze statue of David (circa 1440s) is famous as the first unsupported standing work of bronze cast during the Renaissance, and the first freestanding nude male sculpture made since antiquity. It depicts David with an enigmatic smile, posed with his foot on Goliath's severed head just after defeating the giant. The youth is completely naked, apart from a laurel-topped hat and boots, bearing the sword of Goliath. There are no documents related to the commission or production of the bronze David. The earliest secure reference to the statue occurred in 1469, when it was described at the center of the courtyard of the Medici Palace in Florence. The Medici were exiled from Florence in 1494, and the statue was moved to the courtyard of the Palazzo della Signoria (the marble David was already in the palazzo). It was moved to the Pitti Palace in the 17th century, to the Uffizi in 1777, and then finally, in 1865, to the Bargello museum, where it remains today.[5]

According to Vasari, the statue stood on a column designed by Desiderio da Settignano in the middle of the courtyard of the Palazzo Medici; an inscription seems to have explained the statue's significance as a political monument: "Victor est quisquis patriam tuetur/Frangit immanis Deus hostis iras/En puer grandem domuit tiramnum/Vincite cives" (The victor is whoever defends the fatherland. God crushes the wrath of an enormous foe. Behold! A boy overcame a great tyrant. Conquer, o citizens.)[6] Although a political meaning for the statue is widely accepted, exactly what that meaning is has been a matter of considerable debate among scholars.[7]

Most scholars assume the statue was commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici, but the date of its creation is unknown and widely disputed; suggested dates vary from the 1420s to the 1460s (Donatello died in 1466), with the majority opinion recently falling in the 1440s, when the new Medici Palace designed by Michelozzo was under construction.[8] The iconography of the bronze David follows that of the marble David: a young hero stands with sword in hand, the decapitated head of his enemy at his feet. Visually, however, this statue is startlingly different. Naked, but for hat and shoes, David is both physically frail and strikingly effeminate. His physique, which Mary McCarthy called "a transvestite's and fetishist's dream of alluring ambiguity," contrasted with the absurdly large sword by his side, shows that David has conquered Goliath not by physical prowess, but through the will of God. The boy's nakedness further enhances the idea of the presence of God, contrasting the youth with the heavily-armored giant. David is presented uncircumcised, which is generally customary for male nudes in Italian Renaissance art.[9]

Controversy

There are no indications of contemporary responses to the David, although the statue could not have been placed in the town hall of Florence in the 1490s were it generally viewed as controversial. In the early 16th century, the Herald of the Signoria mentioned the sculpture in a way that suggested there was something unsettling about it: "The David in the courtyard is not a perfect figure because its right leg is tasteless."[10] By mid-century Vasari was describing the statue as so naturalistic that it must have been made from life. However, among 20th and 21st century art historians there has been considerable controversy about how to interpret it.

While the Bible describes David as a beautiful youth, and we can accept a classical basis for the pose and the nudity of the statue (Greco-Roman heroes were typically portrayed as nude males standing in contrapposto), there are nevertheless several disconcerting elements to Donatello's David. David's pose is languid and his expression dreamy, neither of which seems to express the narrative moment. A pre-pubescent boy could not be expected to have the muscular development of an adult, but the softness of his body and the emphasis on his lower stomach strike most viewers as surprisingly effeminate. The nudity can be explained by David's refusal to wear armor in his confrontation with Goliath, as well as by references to classical heroes, but the fact that he wears a hat and boots makes no sense in terms of either the Biblical narrative or the classical connection and tends to make his lack of clothing seem strange. He places his left foot on Goliath's head; on the one hand, this pose allows Donatello to connect David more strongly to his fallen foe than he did in the marble version.

On the other hand, there's something disturbing about the way the beard on the decapitated head curls around David's sandaled foot. Goliath is wearing a winged helmet. David's right foot stands firmly on the short right wing, while the left wing, considerably longer, works its way up his right leg to his groin.

The strangeness of the figure has been interpreted in a variety of ways. One has been to suggest that Donatello was homosexual and that he was expressing that sexual attitude through this statue.[11] A second is to suggest that the work refers to homosocial values in Florentine society without expressing Donatello's personal tendencies.[12] During Classical antiquity, homosexuality had been something that was practiced regularly, and men believed that they could only achieve great love with other men. However, during the time of the Renaissance, when the statue was created, sodomy was illegal, and over 14,000 people had been tried in Florence for this crime.[13] So this homosexual implication was very risky and dangerous. A third interpretation - probably the most accepted among scholars[citation needed] - is that David represents Donatello's effort to create a unique version of the male nude, to exercise artistic license rather than copy the classical models that had thus far been the sources for the depiction of the male nude in Renaissance art.[14] What is certain in this statue is that Donatello has not followed any traditions, and the representation is far from bland. Donatello has spent much time into his art works to get them to look the way that they do today.

Change in identification

The traditional identification of the figure was first questioned in 1939 by Jeno Lanyi, with an interpretation leaning toward ancient mythology, the hero's helmet especially suggesting Hermes. A number of scholars over the last 70 years have followed Lanyi, sometimes referring to the statue as David-Mercury.[15] If the figure were indeed meant to represent Mercury, it may be supposed that he stands atop the head of the vanquished giant Argus Panoptes. However, this identification is certainly mistaken; all quattrocento references to the statue firmly identify it as David.[16]

Restoration

The statue underwent restoration from June 2007 to November 2008. This was the first time the statue had ever been restored, but concerns about layers of "mineralized waxings" on the surface of the bronze led to the 18-month intervention. The statue was scraped with scalpels (on the non-gilded areas) and lasered (on the gilded areas) to remove surface build-up.[17]

Copies and influence

There is a full-size plaster cast (with a broken sword) in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. There is also a full-size white marble copy in the Temperate House at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Surrey, a few miles outside central London. In addition to the copies in the United Kingdom, there is also another copy at the Slater Museum at the Norwich Free Academy in Norwich, Connecticut, United States.[18]

David continued to be a subject of great interest for Italian patrons and artists. Later representations of the Biblical hero include Antonio del Pollaiuolo's David (Berlin, Staatliche Museen, c. 1470, panel painting), Verrocchio's David (Florence, Bargello, 1470s, bronze), Domenico Ghirlandaio's David (Florence, S. Maria Novella, c. 1485, fresco), Bartolomeo Bellano's David (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1470s, bronze), Michelangelo's David (Florence, Accademia, 1501-4, marble), and Bernini's David, (Rome, Galleria Borghese, 1623–24, marble).

Notes

- ^ Raymond-Jean Frontain and Jan Wojcik, eds., The David Myth in Western Literature, West Lafayette, IN, 1980.

- ^ H.W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1957, II, 3-7; John Pope-Hennessey, Italian Renaissance Sculpture, London, 1958, 6-7; Joachim Poeschke, Donatello and his World: Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance, New York, 1990, 27.

- ^ Documents on the statue may be found in Omaggio a Donatello, 1386-1986, exh. cat., Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, 1985, 126-127. On the political implications of David for early-modern Florence, see Andrew Butterfield, ”New Evidence for the Iconography of David in Quattrocento Florence,” I Tatti Studies 6 (1995) 114-133.

- ^ Poeschke, 377;Omaggio, 125.

- ^ Janson, Donatello, 77-78; Poeschke, 397; Omaggio, 196-197; Adrian W.B. Randolph, Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence, New Haven, 2002, 139-141. Randolph published a poem from 1466 that seems to describe the statue in the Medici palace.

- ^ Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite..., ed. G. Milanesi, Florence, 1878-1885, III, 108. A quattrocento manuscript containing the text of the inscription is probably an earlier reference to the statue; unfortunately the manuscript is not dated. Christine M. Sperling, "Donatello's Bronze 'David' and the Demands of Medici Politics," The Burlington Magazine, 134 (1992), 218-219.

- ^ Political readings of the David include Christine Sperling, "Donatello's Bronze "David" and the Demands of Medici Politics," The Burlington Magazine, 134 (1992) 218-224; Roger J. Crum, "Donatello's Bronze David and the Question of Foreign versus Domestic Tyranny," Renaissance Studies, 10 (1996) 440-450; Sarah Blake McHam, "Donatello's Bronze David and Judith as Metaphors of Medici Rule in Florence," Art Bulletin, 83 (2001) 32-47; Allie Terry, "Donatello's decapitations and the rhetoric of beheading in Medicean Florence," Renaissance Studies, 23 (2009) 609-638.

- ^ M. Greenhalgh, Donatello and His Sources, London, 1982, 166.

- ^ Leo Steinberg, "Michelangelo and the Doctors," Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 56 (1982) 552-553.

- ^ G. Gaye, Carteggio inedito d'artisti dei secoli xiv.xv.xvi., 3 vols., Florence, 1840, II: 456: "El Davit della corte è una figura et non è perfecta, perchè la gamba sua di drieto è schiocha." Cited in John Shearman, Only Connect...Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, 22 n. 17. Shearman notes that schiocha could be translated as "imprudent" or "stupid."

- ^ H.W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1957, II, 77-86; Laurie Schneider, "Donatello's Bronze David," The Art Bulletin, 55 (1973) 213-216.

- ^ Randolph, 139-192; name="raymondjeanfrontain">Raymond-Jean Frontain. "The Fortune in David’s Eyes". GLRW. http://www.glreview.com/issues/13.4/13.4-frontain.php..

- ^ See PBS documentary "The Medici", 2003

- ^ See, for example, Poeschke, 398.

- ^ Lanyi never published his hypothesis; his ideas were made public by John Pope-Hennessey in “Donatello’s Bronze David," Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di Federico Zeri Milan: Electa, 1984, 122-127, and further developed by Alessandro Paroncchi, Donatello e il potere, Florence, 1980, 101-115 and G. Fossi, et.al., Italian Art, Florence, 2000, 91.

- ^ See also John Shearman, Only Connect...Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, 20-21.

- ^ http://www.polomuseale.firenze.it/restaurodonatello/

- ^ Shana Sureck (July 14, 2002). "Dusting". Hartford Courant. http://articles.courant.com/2002-07-14/features/0207141124_1_greatest-sculptures-dusting-museum-work. Retrieved 2011 Oct 10.

External links

- Analysis, theme and critical reception

- Discussion & many detailed photos

- Two more angles

- Site with numerous image links

- White marble copy at Kew (part of a set on Flickr)

Donatello Saint Mark (1411-1413) · St. George Tabernacle (c. 1415–1417) · Marzocco (1418-1420) · David (1408-1409) · Prophet Habacuc (1423–1425) · Tomb of Antipope John XXIII (1424-1427) · Tomb of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci (c. 1427-1428) · The Feast of Herod (1425) · David (c. 1440) · Equestrian statue of Gattamelata (1453) · Magdalene Penitent (1453-1455) · Virgin and Child with Four Angels (1456) · Judith and Holofernes (1460)Categories:- Renaissance sculptures

- 1440s works

- Sculptures depicting David

- Sculptures by Donatello

- Bargello

- Quattrocento art

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.