- Anomalocaris

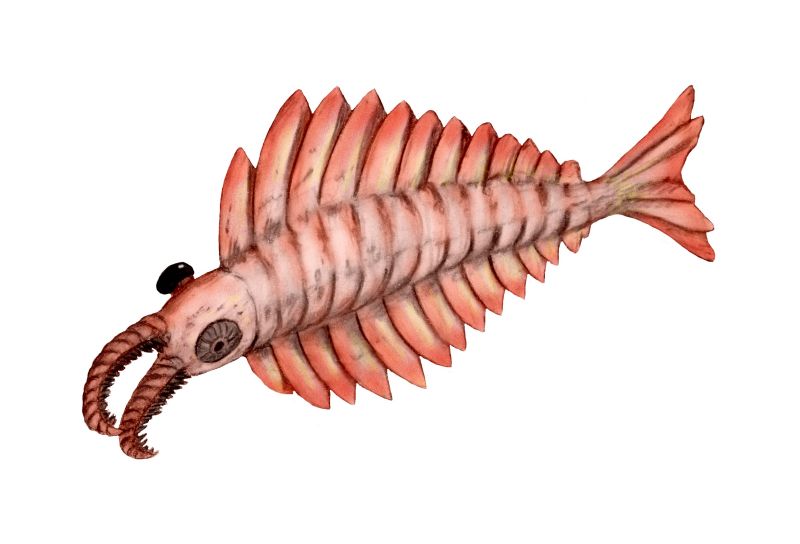

image_caption = "Anomalocaris" from below

fossil_range = Early to midCambrian - fossil range|524 |period end|mid cambrian

domain =Eukaryota

regnum =Animalia

subregnum =Eumetazoa

unranked_phylum =Bilateria

superphylum =Ecdysozoa

unranked_classis =Panarthropoda

phylum =Lobopodia

classis =Dinocarida

ordo =Radiodonta

familia =Anomalocarididae

genus = "Anomalocaris"

genus_authority = Whiteaves 1892

subdivision_ranks = Species

subdivision =

* ?"A. lineata" Resser & Howell, 1938

* "A. canadensis" Whiteaves 1892

* "A. nathorsti" (Walcott 1911)

* "A. saron"

Hou, Bergström & Ahlberg, 1995

* "A. pennsylvanica" Resser, 1929

* "A. briggsi""Anomalocaris" ("Anomalous shrimp") is an extinct genus of

anomalocarid s, which are, in turn, thought to be closely related to thearthropod s. The firstfossil s of Anomalocaris were discovered in the Ogygopsis shale byJoseph Frederick Whiteaves , with more examples found byCharles Doolittle Walcott in the famedBurgess Shale .cite book |author=Conway Morris, S. |title=The crucible of creation: the Burgess Shale and the rise of animals |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford [Oxfordshire] |year=1998 |pages=56-9 |isbn=0-19-850256-7 |oclc= |doi=] Originally several fossilized parts discovered separately (the mouth, feeding appendages and tail) were thought to be three separate creatures, a misapprehension corrected byHarry B. Whittington andDerek Briggs in a 1985 journal article.cite journal | author = Whittington, H.B. | coauthors = Briggs, D.E.G. | year = 1985 | title = The largest Cambrian animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British Columbia | journal = Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. | volume = 309 | pages = 569--609 | doi = 10.1098/rstb.1985.0096]Anatomy

"Anomalocaris" is thought to have been a carnivorous predator, propelling itself through the water by undulating the flexible lobes on the sides of its body.cite web | url = http://www.trilobites.info/anohome.html | title = The Anomalocaris homepage | accessdate = 2008-03-20 ] Anomalocaris had a large head, a single pair of large, possibly compound

eye s, and an unusual, disk-likemouth . The mouth was composed of 32 overlapping plates, four large and 28 small, resembling apineapple ring with the center replaced by a series of serrated prongs. The mouth could constrict to crush prey, but never completely close, and the tooth-like prongs continued down the walls of the gullet.cite book |author=Gould, Stephen Jay |title= |publisher=W.W. Norton |location=New York |year=1989 |pages= 194-206|isbn=0-393-02705-8 |oclc= |doi=] Two large 'arms' (up to seven inches in length when extended) with barb-like spikes were positioned in front of the mouth, and were probably used these to grab prey and bring it to its mouth. The tail was large and fan-shaped, and along with undulations of the lobes, was probably used to propel the creature through Cambrian waters.Usami, Yoshiyuki (2006). Theoretical study on the body form and swimming pattern of "Anomalocaris" based on hydrodynamic simulation. Journal of Theoretical Biology. Volume 238, Issue 1, pp. 11-17] Stacked lamella of what were probablygill s attached to the top of each of a total of eleven lobes.For the time in which it lived "Anomalocaris" was a truly gigantic creature, reaching lengths of up to one meter.

Discovery

"Anomalocaris" has been misidentified several times, in part due to its makeup of a mixture of mineralized and unmineralized body parts; the mouth and feeding appendage was considerably harder and more easily fossilized than the delicate body. Its name originates from a description of a detached 'arm', described by

Joseph Frederick Whiteaves in 1892 as a separatecrustacean -like creature due to its resemblance to the tail of alobster orshrimp . The first fossilized mouth was discovered byCharles Doolittle Walcott , who mistook it for ajellyfish and placed the genus "Peytoia". Walcott also discovered a second feeding appendage but failed to realize the similarities to Whiteaves discovery and instead identified it as feeding appendage or tail of the extinct "Sidneyia ". The body was discovered separately and classified as asponge in the genus "Laggania"; the mouth was found with the body, but was interpreted by its discovererSimon Conway Morris as an unrelated "Peytoia" that had through happenstance settled and been preserved with "Laggania". Later, while clearing what he thought was an unrelated specimen,Harry B. Whittington removed a layer of covering stone to discovered the unequivocally connected arm of thought to be a shrimp tail and mouth thought to be a jellyfish. Whittington linked the two species, but it took several more years for researchers to realize that the continuously juxtaposed "Peytoia", "Laggania" and feeding appendage actually represented a single, enormous creature. According toInternational Commission on Zoological Nomenclature rules, the oldest name takes priority, which in this case would be "Anomalocaris". The name "Laggania " was later used for another genus of anomalocarid. "Peytoia" has been modified into "Parapeytoia ", a genus of Chinese anomalocarid. Anomalocaris is placed in the extinct familyAnomalocaridae , and is now considered to be related to modernarthropod s.Stephen Jay Gould cites "Anomalocaris" as one of the fossilized extinct species he believed to be evidence of a much more diverse set phyla that existed in theCambrian era (discussed in his book "Wonderful Life"), a conclusion disputed by other paleontologists.Ecology

"Anomalocaris" had a cosmopolitan distribution in Cambrian seas, and has been found from early to mid Cambrian deposits from Canada, China, Utah and Australia, to name but a few.citation

author = Briggs, Derek E. G.

year = 1994

title = Giant Predators from the Cambrian of China

journal = Science

volume = 264

issue = 5163

pages = 1283–1284

doi = 10.1126/science.264.5163.1283

url = http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/citation/264/5163/1283

pmid = 17780843] citation

author = Briggs, D.E.G.; Mount, J.D.

year = 1982

journal = Journal of Paleontology

volume = 56

issue = 5

pages = 1112–1118

url = http://jpaleontol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/56/5/1112

publisher = Paleontological Soc] Citation

author = Briggs, D.E.G.; Robison, R.A.

title =Exceptionally preserved nontrilobite arthropods and Anomalocaris from the Middle Cambrian of Utah

year = 1984

url = http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/handle/1808/3656

publisher = The Paleontological Institute, The University of Kansas]It appears to have fed on other animals, including trilobites. Some Cambrian trilobites have been found with W-shaped "bite" marks which seemed to match the mouthparts of "Anomalocaris". However, since "Anomalocaris" lacks any mineralised tissue, it seemed unlikely that it would be able to penetrate the tough, calcified shell of trilobites.It turns out that Anamolacarids fed by grabbing one end of their prey in their jaws while using their appendages to quickly rock the other end of the animal back and forth. This produced stresses that exploited the weaknesses of arthropod cuticle, causing the prey's exoskeleton to rupture and allowing the predator to access its innards. This behaviour is thought to have provided an evolutionary pressure for trilobites to roll up, to avoid being flexed until they snapped.citation

author = Nedin, C.

year = 1999

title = "Anomalocaris" predation on nonmineralized and mineralized trilobites

journal = Geology

volume = 27

issue = 11

pages = 987–990

doi = 10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0987:APONAM>2.3.CO;2

url = http://geology.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/27/11/987]Further evidence that "Anomalocaris" ate trilobites comes from fossilised faecal pellets, which contain trilobite parts and are so large that the Anomalocarids are the only organisms large enough to have produced them.

Gallery

ee also

Classification is discussed at

Anomalocarididae .Other relevant articles are:*

Cambrian explosion

*Opabinia

*Wiwaxia Footnotes

References

*cite book |author=Paul Chambers; Haines, Tim |title=

The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life |publisher=Firefly Books |location=Buffalo, N.Y |year= |pages= |isbn=1-55407-181-X |oclc= |doi=External links

* [http://www.trilobites.info/anohome.html "Anomalocaris" 'homepage' with swimming animation]

* [http://paleobiology.si.edu/burgess/anomalocaris.html Burgess Shale: Anomalocaris canadensis (proto-arthropod)] , Smithsonian.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.