- Anthony Burns

-

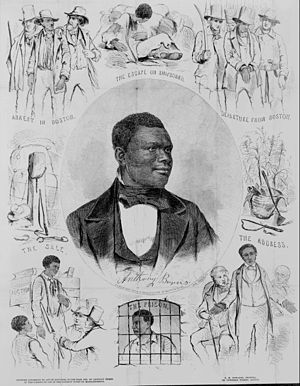

A portrait of the fugitive slave Anthony Burns, whose arrest and trial under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 touched off riots and protests by abolitionists and citizens of Boston in the spring of 1854. A bust portrait of the twenty-four-year-old Burns, "Drawn by Barry from a daguereotype [sic] by Whipple and Black," is surrounded by scenes from his life.

A portrait of the fugitive slave Anthony Burns, whose arrest and trial under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 touched off riots and protests by abolitionists and citizens of Boston in the spring of 1854. A bust portrait of the twenty-four-year-old Burns, "Drawn by Barry from a daguereotype [sic] by Whipple and Black," is surrounded by scenes from his life.

Anthony Burns (31 May 1834 – 17 July 1862) was born a slave in Stafford County, Virginia. As a young man, he became a Baptist and a "slave preacher". 1850 would prove a vital year in Burns' life because of the passage of the new Fugitive Slave Act that required states to cooperate in returning escaped slaves to their masters, even if recaptured in northern states that had abolished slavery. Burns was affected by the law after he became a fugitive in Massachusetts.

He was captured and tried under the law in Boston, in a case that generated national publicity, large demonstrations, protests and an attack on US Marshals at the courthouse. Federal troops were used to ensure Burns was transported to a ship for return to Virginia after the trial. He was eventually ransomed from slavery, with his freedom purchased by Boston sympathizers. Afterward he was educated at Oberlin College and became a Baptist preacher, moving to Upper Canada for a position.

Contents

Flight from slavery and capture

At the age of nineteen, Anthony Burns escaped slavery in Richmond, traveling by ship to Boston in 1853. In Boston he worked for "Coffin Pitts, clothing dealer, no.36 Brattle Street."[1]

On May 24, 1854 he was discovered "while walking in Court Street" and arrested.[2] As a hub of resistance toward the "slave power" of the South, many Bostonians reacted by attempting to free Burns. President Franklin Pierce made an example of the case to show he was willing to strongly enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. The show of force turned many New Englanders against slavery who had passively accepted its existence before.

On May 26, before Burns' court case, a crowd of abolitionists of both races, including Thomas Wentworth Higginson and other Bostonians outraged at Burns' arrest, stormed the court house to free the man.[3] In the melee, Deputy U.S. Marshal James Batchelder was fatally stabbed,[4] becoming the second U.S. Marshal to be killed in the line of duty.[5] The police kept control of Burns, but the crowds of opponents, including such African-American abolitionists as Thomas James grew large.[6] While the federal government sent US troops in support, numerous anti-slavery activists arrived in Boston to join the protest and continue the faceoff. It has been estimated the government's cost of capturing and conducting Burns through the trial was upwards of $40,000.[7]

Trial and aftermath

Burns's trial was a formality as the requirements of the Fugitive Slave Act were clear. Richard Henry Dana, Jr. and his associate, the African-American lawyer Robert Morris, acted as Burns' defenders, but were not successful in the case. With the ruling made against Burns, the government effectively held Boston under martial law for the afternoon. The streets between the courthouse and the harbor were lined with federal troops to hold back the waves of protesters as Burns was escorted to the ship for return to his Virginia master.

The matter did not end as Burns was transported south. The events generated strong opposition across the North to Pierce and his administration. Massachusetts residents formed an Anti-Man Hunting League; William Lloyd Garrison's burned copies of the Fugitive Slave Act, the Burns court decision, and the Constitution of the United States; and, as a result of the efforts of the Vigilance Committee to lobby the legislature and governor against him, the removal from office in 1857 of Edward G. Loring, the judge who tried Burns. (The next year Loring was appointed to the US Court of Claims under President James Buchanan.) In a broader sense, the Burns case fueled anti-slavery sentiments all across the North.

“ We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad Abolitionists. ” Freedom and later life

The abolitionist community in Boston raised $1,200 to buy Burns' freedom from his master, Charles F. Suttle, but Suttle refused to deal with anyone seeking Burns' emancipation. After Burns was transported to Virginia, Suttle sold him for $905 to David McDaniel, a slaver, cotton planter, and horse-dealer from Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Leonard A. Grimes eventually managed to ransom Burns's freedom from McDaniel, with financial aid from Boston, for $1,300. Once freed, Burns returned to live in Boston.

With proceeds that came from his biography, combined with a scholarship, Burns received an education at Oberlin College in Ohio. After briefly preaching in Indianapolis, Burns emigrated to Upper Canada to accept a call from a Baptist church in that colony. He served as a non-ordained minister until his early death from tuberculosis at the age of 28 in St. Catharines on July 17, 1862.

Sources

- Tuttleton, James W., Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Twayne Publishers. pp. 34-36

- Charles Emery Stevens (1856), Anthony Burns: A History.

- “Anthony Burns Biography (1834-1862).” A&E Television Networks. 2007. <http://www.biography.com/search/article.do?id=9232120>

- “Anthony Burns (1834-1862)”, Black Abolitionist Archive, University of Detroit Mercy. <http://image.udmercy.edu/BAA/Anthony_Burns.html>

- Stewart, James Brewer, and Eric Foner. Holy Warriors: The Abolitionists and American Slavery, revised edition. New York: Hill and Wang, 1996.

- Zebly, Kathleen R. "Anthony Burns", in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. ed. Hedler, David S. and Hedler, Jeanne T. (2000) ISBN 0-393-04758-X

Notes and references

- ^ Boston slave riot, and trial of Anthony Burns: Containing the report of the Faneuil Hall meeting, the murder of Batchelder, Theodore Parker's Lesson for the day, speeches of counsel on both sides, corrected by themselves, a verbatim report of Judge Loring's decision, and detailed account of the embarkation. Boston: Fetridge and Co., 1854; p.5

- ^ Boston Slave Riot. 1854; p.5

- ^ Zebley p. 326

- ^ Stevens, p. 43

- ^ "Roll Call of Honor". http://www.usmarshals.gov/history/roll_call.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ James, Thomas. Life of Rev. Thomas James, by Himself, Rochester, N.Y.: Post Express Printing Company, 1886, at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, accessed 3 Jun 2010

- ^ The "Trial" of Anthony Burns, Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed May 10, 2010.

- ^ McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Bantam Books, 1989), p. 120

See also

- “Slavery in Massachusetts”, Henry David Thoreau’s reaction to the Burns trial

Further reading

- PBS Resource Bank: People and Events: Anthony Burns captured, 1854

- Ronica Roth (2003): "The Trial of Anthony Burns", in Humanities, May/June 2003, Volume 24/Number 3.

- Virginia Hamilton, Anthony Burns: The Defeat and Triumph of a Fugitive Slave

- Henry David Thoreau (July 4, 1854): "Slavery in Massachusetts"

"Burns, Anthony". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Burns, Anthony". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

Categories:- American slaves

- African American religious leaders

- Oberlin College alumni

- 1834 births

- 1862 deaths

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.