- Nonconcatenative morphology

-

Nonconcatenative morphology, also called discontinuous morphology and introflection, is a form of word formation in which the root is modified and which does not involve stringing morphemes together.[1] In English, for example, while plurals are usually formed by adding the suffix -s, certain words use nonconcatenative processes for their plural forms:

- foot /fʊt/ → feet /fiːt/;

and many irregular verbs form their past tenses, past participles, or both in this manner:

- freeze /friːz/ → froze /froʊz/, frozen /'froʊzən/.

This specific form of nonconcatenative morphology is known as base modification or ablaut, a form in which part of the root undergoes a phonological change without necessarily adding new phonological material. Other forms of base modification include lengthening of a vowel, as in Hindi:

- /mar-/ "die" ↔ /maːr-/ "kill"

or change in tone or stress:

- Chalcatongo Mixtec /káʔba/ "filth" ↔ /káʔbá/ "dirty"

- English record /ˈrɛkərd/ (noun) ↔ /rɨˈkɔrd/ "to make a record"

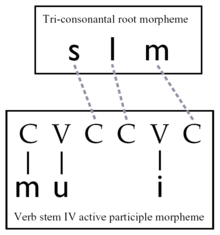

Another form of nonconcatenative morphology is known as transfixation, in which vowel and consonant morphemes are interdigitized. For example, depending on the vowels, the Arabic consonantal root k-t-b can have different but semantically-related meanings. Thus, [katab] 'he wrote' and [kitaːb] 'book' both come from the root k-t-b. In the analysis provided by McCarthy's account of nonconcatenative morphology, the consonantal root is assigned to one tier, and the vowel pattern to another.[2]

Yet another common type of nonconcatenative morphology is reduplication, a process in which all or part of the root is reduplicated. In Sakha, this process is used to form intensified adjectives:

/k̠ɨhɨl/ "red" ↔ /k̠ɨp-k̠ɨhɨl/ "flaming red".

A final common type of nonconcatenative morphology is variously referred to as truncation, deletion, or subtraction; the morpheme is sometimes called a disfix. This process removes phonological material from the root, as in Murle:

/oɳiːt/ "rib" ↔ /oɳiː/ "ribs".

Nonconcatenative morphology is extremely well developed in the Semitic languages, where it forms the basis of virtually all higher-level word formation (as with the example given in the diagram). This is especially pronounced in Arabic, where it is also used to form approximately 90% of all plurals; see broken plural.

See also

References

- ^ Haspelmath, Martin (2002). Understanding Morphology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-340-76026-5.

- ^ McCarthy, John J. (1981). "A Prosodic Theory of Nonconcatenative Morphology". Linguistic Inquiry 12: 373–418.

Categories:- Linguistic morphology

- Semitic linguistics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.