- Mary Eleanor Bowes, Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorne

-

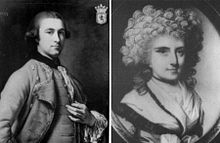

Mary Eleanor Bowes and her husband John Lyon.

Mary Eleanor Bowes and her husband John Lyon.

Mary Eleanor Bowes, Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorne (24 February 1749 – 28 April 1800), known as "The Unhappy Countess", was the daughter and heiress of George Bowes. Some of her children with John Lyon hyphenated their parents' names, styling themselves Bowes-Lyon.

Mary Eleanor Bowes was well-educated for her time, and in 1769 published a poetical drama entitled The Siege of Jerusalem (see 1769 in literature, 1769 in poetry). She was also enthusiastic about botany, sending William Paterson to the Cape in 1777 to collect plants on her behalf.

Contents

Early life

Mary's father died when she was eleven years old, and left her a vast fortune (estimated at between £600,000 and £1,040,000) which he had built up through control of a cartel of coal-mine owners. At a stroke Mary became the wealthiest heiress in Britain - some said Europe - and she encouraged the attentions of Campbell Scott, younger brother of Henry Scott (the Duke of Buccleuch) as well as John Stuart, the self-styled Lord Mountstuart, eldest son of Lord Bute, before becoming engaged at the age of sixteen to John Lyon.

She married John Lyon, the 9th Earl of Strathmore on her eighteenth birthday, 24 February 1767. Since her father's will stipulated that her husband should assume his wife's family name, the Earl addressed Parliament, and his name was changed to John Bowes.

On the basis of Mary's fortune, the couple lived extravagantly and had five children:

- Maria Jane Bowes (who later styled herself Bowes-Lyon) (21 April 1768 - 22 April 1806), married 1789 Colonel Barrington Price, of the British Army

- John Bowes, 10th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne (13 April 1769 - 3 July 1820), married Mary Milner, his long-term mistress and mother of his son, on 2 July 1820, the day before he died

- Anna Maria Bowes (3 June 1770 - 29 March 1832), eloped and married Henry Jessop in 1788

- George Bowes (17 November 1771 - 3 December 1806), married Mary Thornhill

- Thomas Bowes-Lyon, 11th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne (3 May 1773 - 27 August 1846) married Mary Elizabeth Louisa Rodney Carpenter; his wife was the granddaughter of a plumber, whose daughter married one of his wealthy clients.

Her husband spent much of his time drinking and restoring Glamis Castle so that "to amuse herself"[1] she wrote her verse drama, The Siege of Jerusalem (1769). The Earl showed little interest in his wife except as a breeder of children, and she took comfort elsewhere and by the time of his death was pregnant by a lover, George Gray, a Scottish 'nabob' who had made and squandered a small fortune working for the East India Company. Born in Calcutta in 1737, where his father had worked as a surgeon for the company, Gray had returned to England under a cloud in 1766. Samuel Foote's play The Nabob is believed to have been informed by his friendship with Gray, who was also a friend of James Boswell. On 7 March 1776, Lord Strathmore died at sea on his way to Portugal, from tuberculosis.

Second marriage

Upon the death of her first husband, who had left debts totalling a staggering £145,000, in March 1776 Mary Eleanor Bowes regained control of her fortune centred on the mines and farms around her childhood home of Gibside in County Durham. Already pregnant by Gray, she successfully induced an abortion by drinking 'a black inky kind of medicine'[2] and upon becoming pregnant repeatedly again, underwent two further abortions. Her candid account of these abortion attempts is one of the very few first-person descriptions of abortions in history before legalisation. When she found herself pregnant by Gray a fourth time, she resigned herself to marrying him and they became formally engaged in August 1777. But that same summer Mary Eleanor was seduced by a charming and wily Anglo-Irish adventurer, Andrew Robinson Stoney, who manipulated his way into her household and her bed. Calling himself 'Captain' Stoney—although he was in reality a mere lieutenant in the British Army—he insisted on fighting a duel in Mary's honour with the editor of The Morning Post newspaper which had published scurrilous articles about her private life. In fact Stoney had himself written the articles both criticising and defending the countess and faked the duel with the editor, Revd Henry Bate, in an attempt to appeal to Mary's romantic nature. Pretending to be mortally wounded, he begged Mary to grant his dying wish: to marry her. Stoney was carried on a stretcher down the aisle of St James's Church, Piccadilly, where he married Mary Eleanor on 17 January 1777. In compliance with her father's will, Stoney changed his name to Bowes. There were two children within this marriage. Mary Bowes, who was probably the daughter of George Gray, was delivered secretly in August 1777 but her birthday was registered as 14 November 1777. William Johnstone Bowes was born on 8 March 1782.

Stoney Bowes (who, it was commonly supposed, had already caused the death of a previous wife, Hannah Newton, in order to obtain her inheritance) immediately attempted to take control of Mary's fortune. When he discovered that she had secretly made a prenuptial agreement safeguarding the profits of her estate for her own use, he forced her to sign a revocation handing control to him. Squandering the wealth, he subjected the countess to eight years of physical and mental abuse. Among other outrages he imprisoned her in her own house, and carried her and her daughter Anna Maria (by Strathmore) off to Paris, whence they returned only after a writ had been served on him. At the same time he raped the maids, invited prostitutes into the home and fathered numerous illegitimate children.

Finally, in 1785, with the help of loyal maids, the countess managed to escape his custody and filed for divorce through the ecclesiastical courts. Having lost the first round of this courtroom battle, Stoney Bowes abducted Mary with the help of a gang of accomplices, carried her off to the north country, threatened to rape and to kill her, gagged and beat her, and carried her around the countryside on horseback in one of the coldest spells of the coldest winter of the century. The country was alerted, and Stoney Bowes was eventually arrested and the countess rescued.

The legal battles continued. Stoney Bowes and his accomplices were found guilty of conspiracy to abduct Mary, and he was sentenced to three years in prison. Meanwhile he lost the divorce case and the battle to hang on to the Bowes fortune. The trials were sensational and the talk of London. Although the countess initially won public sympathy, Bowes eventually turned many against her — partly because of the libels he succeeded in putting about (buying shares in a newspaper for the purpose and publishing the 'Confessions' he had earlier forced her to write) — and partly because the general apprehension was that she had behaved badly in attempting to prevent her husband's access to her fortune. There had also been an affair between her and the brother of one of the lawyers, which became public knowledge, and, Stoney Bowes alleged, an affair with her footman, George Walker. The divorce was finalised in a trial at the High Court of Delegates which revealed how Bowes had systematically deprived the countess of her liberty and abused her. Stoney Bowes died, still under prison jurisdiction although living outside the prison walls, on 16 June 1810.

In 1841, the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray heard Bowes's life story from the Countess's grandson, John Bowes, and used it in his novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon.

Retirement

After 1792, the countess lived quietly in Purbrook Park in Hampshire. She later moved to Stourfield House, an isolated mansion on the edge of the village of Pokesdown near Christchurch, Hampshire, where she could live feeling that she was "...out of the world.."

Local people found the countess very strange, if not actually mad, but once they heard of her tribulations they understood that she had good reasons to be odd. Mary's sons by Lyon seldom visited their mother, and never stayed for long, but two daughters lived with her, Lady Jessop from her first marriage, and Miss Bowes from the second.

Mary brought to Stourfield a full establishment of servants, and a dearly loved companion Mary Morgan, the maid who had helped her escape her marital home, who died in 1796 and was buried at Christchurch beneath a brass plaque composed by Lady Strathmore to honour her friend. Following this death the countess did not socialise at all, she spent most of her time looking after pet animals, including a large number of dogs, for whom hot dinners were cooked daily. The countess offered £10 reward when one of the dogs "Flora" went missing in 1798. It was found dead by Farmer Dale, who declined the reward, on account of the great kindnesses previously shown by the countess to him and his wife.

She frequently had dinners cooked for men working in the fields, and had sent beer out to refresh them. One of the countess's few joys was to see her daughter Miss Bowes learning to ride. She used to ride a dozen miles before breakfast, and managed to remain seated when her mount attempted to roll in the river at Iford one hot day, which won her great admiration from the locals. At this time riding gave great independence, journey times were about a third that of going by coach.

Miss Bowes also followed her mother's example, and was constantly generous to the poor of the area. Towards the close of the century Lady Strathmore called in some trusted friends from Pokesdown village to witness her final will, and began making presents of dresses and other items to the community. She also left an annuity for Widow Lockyer of Pokesdown Farm, which her daughter Lady Jessop continued to pay until she moved to Ringwood, Mr Colby administered the annuity then, until Widow Lockyer's death.

Mary died in 1800. According to the locals the countess was buried as requested in a court dress, with all the accessories necessary for a Royal audience, plus a small silver trumpet. Other reports have it that she was buried in a bridal dress. Undertakers came down from London with a hearse and three mourning carriages, and Mary was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey.

Soon after this the contents of Stourfield house were sold. Mr. Bowes was released from prison on her death, and unsuccessfully attempted to invalidate Mary's will. When he lost the case he was sued by his own lawyers for their expenses. Unable ever to repay his debts he remained under prison jurisdiction although he lived outside the prison walls with his latest mistress, Mary 'Polly' Sutton, who he treated as abysmally as his two wives and their five children. Bowes died in 1810.

Details of Mary's life at Stourfield House were preserved in the transcribed memories of an elderly Pokesdown resident. As an immediate legacy Mary left the villagers with memories of a woman whom they loved and respected for her continuing generosity. A later legacy, which has lasted far longer than Mary's fame, is her name. The Earls of Strathmore, from whom the Queen Mother (died 2002) descends, still use Bowes-Lyon as the family name.

Her tombstone is in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey.

References

- Arnold, Ralph, The Unhappy Countess (1957)

- Foot, Jesse, The Lives of Andrew Robinson Bowes, Esq., and the Countess of Strathmore, written from thirty-three years professional attendance, from Letters and other well authenticated documents (1810)

- Marshall, Rosalind K., Bowes, Mary Eleanor, Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorne (1749–1800), H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, 18 November 2006 (oxforddnb.com)

- Parker, Derek, The Trampled Wife (2006)

- Moore, Wendy, Wedlock: How Georgian Britain's Worst Husband Met his Match (2009)

- Mary Eleanor Bowes, Confessions of the Countess of Strathmore, written by herself. Carefully copied from the original lodged in Doctor's Commons. (1793, British Library)

External links

Categories:- 1749 births

- 1800 deaths

- Bowes-Lyon family

- British countesses

- English dramatists and playwrights

- English writers

- People from Hampshire

- Women dramatists and playwrights

- 18th-century women writers

- English women writers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.