- Drug classification: making a hash of it?

-

Drug classification: making a hash of it? is the title of a report authored by the UK Science and Technology Select Committee and submitted to the British House of Commons. It was published in July 2006. The report suggested that the current system of recreational drug classification in the UK was arbitrary and unscientific,[1] and suggested a more scientific measure of harm be used for classifying drugs. The report also strongly criticised the decision to place fresh psychedelic mushrooms in Class A—the same category as cocaine and heroin.

Contents

Report

Authors

Background

Drug classification: making a hash of it? formed part of a major inquiry, launched in November 2005, into the Government’s handling of scientific advice, risk and evidence in policy-making.[2] The report was the second of three reports into different areas of policy: the first report ("Watching the Directives: Scientific Advice on the EU Physical Agents (Electromagnetic Fields) Directive") examined the EU Physical Agents (Electromagnetic Fields) Directive; the third ("Identity Card Technologies: Scientific Advice, Risk and Evidence"[note 1]) examined the government's ID cards proposal.

Context

A legal loophole meant that fresh magic mushrooms were not treated as controlled drugs, providing that they had not been 'prepared' (i.e. dried, packaged, cooked, etc.). The government made them a controlled substance by means of a clarification to the law, rather than as a reclassification decision, and there was thus no obligation to consult the ACMD.[3] Whilst the government did consult the ACMD, there was not the full consultation process there ordinarily would be.[3]

Findings and recommendations

ACMD

The working practices—primarily, excessive secrecy and a resulting lack of transparency—of the Council were criticised:

We do not accept that the majority of the Council’s work requires the level of confidentiality currently being exercised. The ACMD should, in keeping with the Code of Practice for Scientific Advisory Committees, routinely publish the agendas and minutes for its meetings, removing as necessary any particularly sensitive information.

It was recommended that future meetings be made open to the public, so as to strengthen public confidence in the Council. The Chairman was specifically criticised for showing little interest in improving the Council's approach with regards to transparency. The Council was also criticised for undertaking decisions in relation to methylamphetamine (see also: #Ecstacy and amphetamines) for apparently political reasons.[4]

The report made several recommendations relating to the operations and composition of the ACMD, on the basis that it holds a critical role as the only body which the Home Office is legally obligated to consult before undertaking decisions relating to drugs policy.[5] The report remarked that it was "perturbing" that the Chairman of the ACMD and the Home Secretary hold contradictory views on drugs classification,[6] and also suggested that the term of the Chairman of the ACMD be limited to five years.[7] With regards to what the more general approach in relation to the ACMD should be, the report recommended that: that provision be made for departments other than the Home Office to benefit from the advice of the ACMD, as "the current levels of co-ordination appear to be entirely inadequate";[8] that the ACMD should more proactively give scientific advice in relation to drugs policy to the Department for Education and Skills and to the Department for Health;[9] that the composition and workings of the ACMD be independently reviewed every five years;[10] and that the Chairman of the Council always be accompanied by another Council member in meetings with ministers[11] (although it was emphasised that it did not recommend this because it believed that the current Chairman had acted improperly[12]).

Cannabis

The report stated that changes to drugs policy and especially to the classification of individual drugs must be accompanied by an adequate information campaign.[13] It noted that the government of the time was beginning to understand the implications of muddying the water regarding drugs classification, and quoted Charles Clarke (then-home secretary) in his implicit criticism[14] of his predecessors' actions:

The thing that worries me most [about the decision to move cannabis to Class C] is confusion among the punters about what the legal status of cannabis is[15]

It agreed with Clarke and cited the widespread confusion today over the legal status of cannabis as evidence of a failure by previous governments to adequately educate the public on drugs policy changes.[16]

Gateway theory

The report found that there was no evidence to support the Gateway theory, which holds that the use of legal drugs such as tobacco and alcohol can lead to the subsequent misuse of illegal drugs and that the use of "soft drugs" such as cannabis can lead to the abuse of harder drugs such as heroin:

Even if the gateway theory is correct, it cannot be a very wide gate as the majority of cannabis users never move on to Class A drugs… The gateway theory has little evidence to support it despite copious research.[note 2]

Professor Blakemore remarked that whilst the attitude to cannabis use in the Netherlands is more relaxed than it is in this country and whilst cannabis use amongst the population there is a little less than it is in this country, hard drug use is about one third of the rate in this country (thus debunking the Gateway theory).[17]

Magic mushrooms

The report criticised the way in which magic mushrooms (above) were made illegal by the government in 2005 (although it did not produce a finding on the merits of the actual decision to do so).

The government's decision to outlaw magic mushrooms and classify them as a Class A controlled drug by means other than a reclassification meant that the ACMD was not properly consulted as would otherwise have been required by law. The report criticised this[18] and criticised the Chairman of the Council for allowing this[19] and the Council generally for not speaking out at the time.[20]

Ecstacy and amphetamines

The report criticised the Council for having not reviewed the Class A status of MDMA (Ecstasy) in light of its "widespread usage amongst certain groups".[21] The decision of the Council to not review the classification of Methamphetamine because of the signal that reclassification might send to potential users was heavily criticised,[22] with the report remarking that "[to invoke this nonscientific judgement call as the primary justification for its position [regarding Amphetamine] has muddied the water with respect to its role."[23]

Revision to drug classification

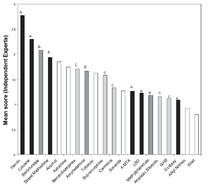

In a report recently published in the Lancet Journal, researchers have introduced an alternative method for drug classification in the UK.[24] This new system uses a “nine category matrix of harm, with an expert Delphic procedure, to assess the harms of a range of illicit drugs in an evidence-based fashion.” The categories of harm included 3 main categories and 3 subcategories for each:

- Physical harm

- (a) Acute

- (b) Chronic

- (c) Intravenous harm

- Dependence

- (a) Intensity of pleasure

- (b) Psychological dependence

- (c) Physical dependence

- Social harm

- (a) Intoxication

- (b) Other social harms

- (c) Health-care costs

The researchers used the proposed classification system to test illegal and some legal substances including alcohol and tobacco among others. The new classification system suggested that heroin, cocaine, alcohol, benzodiazepines, amphetamine, and tobacco have a high or a very high risk of harm, whilst Cannabis, LSD, and Ecstasy were all below the two legal drugs.[25]

Response

Media

Government

Notes

References

- ^ House of Commons, Science and Technology committee (2006-06-31). "Drug classification: making a hash of it?". http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200506/cmselect/cmsctech/1031/1031.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ pg 1

- ^ a b pg 55

- ^ Recommendation 27

- ^ Recommendation 2

- ^ Recommendation 4

- ^ Recommendation 10

- ^ Recommendation 6

- ^ Recommendation 7

- ^ Recommendations 14 and 15

- ^ Recommendation

- ^ p. 19 pg 34

- ^ Recommendation 16

- ^ p 23 pg 46: ", deviated from the Government line ... his predecessors' actions

- ^ We misled public over downgrading cannabis, The Times, 5 January 2006 — in Drugs classification: making a hash of it? pg46

- ^ Recommendations 17 & 18 and paragraphs 47 & 50

- ^ pg 52

- ^ Recommendation 20

- ^ Recommendation 21

- ^ Recommendation 22

- ^ Recommendation 24

- ^ Recommendation 25

- ^ pg 66

- ^ Nutt, D.; King, L. A.; Saulsbury, W.; Blakemore, C. (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- ^ Science and Technology committee 2006, p. 176.

External links

Categories:- Drugs in the United Kingdom

- Government reports

- Politics of the United Kingdom

- Physical harm

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.