- Double-headed serpent

-

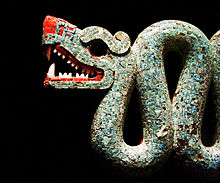

Double-headed serpent

Material Wood, Turquoise, Pine resin, Shell and others Size 20.5 by 43.3 cm Created 15th/16th century Place Made in Mexico Present location Room 25, British Museum, London The Double-headed serpent is an Aztec statue kept at the British Museum. Composed of mostly turquoise pieces applied to a wood base, it is one of nine mosaics of similar material in the British Museum; there are thought to be about 25 such pieces from that period in the whole of Europe.[1] It came from Aztec Mexico and might have been worn or displayed in religious ceremonies.[2] It is possible that this sculpture may be one of the gifts given by the Aztec emperor, Moctezuma II, to Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés when he invaded in 1519.[2] The mosaic is made of pieces of turquoise, crab shell and conch shell.[3]

Contents

Description

The body of the sculpture has been carved from wood. The back of this model is very plain, and only the heads have decorations on both sides. The body has been hollowed out to make the sculpture lighter. The main body of the snake at the front is covered in turquoise. The stone has been broken into similar sized pieces and then stuck to the wooden body with pine resin. By using 2,000[4] small pieces, the flat pieces of stone give the impression of a smooth curved mosaic surface. It has to be remembered that this sculpture was created without the use of iron tools. The turquoise had to be cut and ground using harder stones.[5]

Some of the turqoise had been brought 1,600 km to become part of this serpent.[4]

The heads of the snake have holes for eyes, but there is evidence that beeswax may have been used to hold something that appeared to be an eye. It has been speculated that the material that once made the serpent's eyes was a piece of iron pyrite (Fool's Gold). The vivid contrast of the red and white details on the head have been made from crab shell and snail shell respectively.[6] Cleverly, the adhesive used to attach the Spondylus shell has been coloured with red iron oxide (haematite) to complete the design. The white shell used for the teeth comes from shells of the edible sea snail (Queen Conch).[3][6]

Provenance

It is not known how this sculpture left Mexico, but it is considered possible that it was amongst the goods given to the conquistador Hernando Cortez when he was sent to take the interior of Mexico for the Spanish crown. Cortes arrived on the coast of what is now Mexico in 1519, and after battles he entered the capital on November 8, 1519 and was met with respect, if not favour, by the Aztec ruler Moctezuma II. Some sources report that Moctezuma thought that Cortes was the feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl and treated him accordingly.[7] Cortes was given a number of valuable gifts, which included turquoise sculptures, and possibly this serpent. Despite the gifts and the peaceful reception, Moctezuma was taken prisoner by Cortes and his troops took the Moctezuma's capital, Tenochtitlan, by 1521. The Aztecs lost and they then fell victim to smallpox and other European diseases brought to Mexico by Cortez and his troops.[2]

The Cortez antiquities arrived in Europe in the 1520's and caused great interest; however, it is said that other turqoise mosaics ended their days in jewellers in Florence where they were dismantled to make more contemporary objects. Neil Macgregor credits Henry Christy with gathering similar artifacts into the British Museum.[8]

The sculpture is now in the possession of the British Museum and was purchased by the Christy Fund.

Significance

This sculpture is one of nine Mexican turquoise mosaics in the British Museum and the turqouise double-headed serpent is currently in Room 25. There are considered to be only 25 Mexican turquoise mosaics in Europe from this period.[1]

There were a number of reasons why the serpent may have been chosen as the subject of this sculpture. It has been proposed that the serpent was a symbol of rebirth because of its ability to shed its old skin and appear as a reborn snake. The snake features strongly in the gods that the people worshiped. The feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl was important to their religion,[2] but other gods also had serpentine characteristics.

History of the World

This sculpture featured in A History of the World in 100 Objects, a series of radio programmes that started in 2010 as a collaboration between the BBC and the British Museum.[9]

References

- ^ a b Mexican turquoise mosaics, British Museum, accessed 28 August 2010

- ^ a b c d Double headed serpent, A History of the World in 100 Objects, BBC. accessed 27 August 2010

- ^ a b Double-Headed Serpent, British Museum, accessed September 2010

- ^ a b Neil, Macgregor. "Double Headed Serpent". A History of the World in 100 Objects. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode78/. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ Question, Karl Taube, Mexicolore.co.uk, June 2006, accessed August 2010

- ^ a b Turquoise mosaics from Mexico, Colin McEwan, p.32-3, 2003, British Museum, accessed 29 August 2010

- ^ Herman Cortes, Latin Library, accessed August 2010

- ^ Turquoise mosaics from Mexico, Colin McEwan, Introduction by Neil MacGregor, p.3, 2003, British Museum, accessed 28 August 2010

- ^ A History of the World in 100 Objects, BBC. accessed August 2010

Preceded by

77: Benin BronzesA History of the World in 100 Objects

Object 78Succeeded by

79: Kakiemon elephantsCategories:- Aztec artifacts

- Aztec legendary creatures

- Legendary serpents

- Mexican culture

- Artefacts from Africa, Oceania and the Americas in the British Museum

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.