- Consolidation Coal Company (Iowa)

-

For the much larger company that operated under the same name in the eastern United States, see Consol Energy.

The Consolidation Coal Company was created in 1875 and purchased by the Chicago and North Western Railroad in 1880 in order to provide a local source of coal. The company originally operated at Muchakinock in Mahaska County, Iowa, until the coal resources of that area were largely exhausted. In 1900, the company purchased 10,000 acres (40 km2) in southern Mahaska County and northern Monroe County, Iowa. The company built the town of Buxton in Northern Monroe County, and moved its headquarters there. Consolidation's Mine No. 18 in Buxton was probably the largest bituminous coal mine in Iowa.[1] In 1914, Buxton was the largest town "populated and governed entirely or almost entirely by Negros" in the United States.[2]

Consolidation was one of the very first northern industrial employers to make large-scale use of African American labor. As such, it helped pave the way for the Great Migration of the early 20th century.

Contents

Muchakinock

Also spelled Muchachinock[3] and more rarely Muchikinock.[4] Coal mining along Muchakinock creek dates back to 1843, when local blacksmiths mined coal from exposures along the creek. By 1867, there were small drift mines all along Muchakinock Creek down to Eddyville where the creek flows into the Des Moines River. In 1873, the Iowa Central Railroad built a branch along Muchakinock Creek. The Consolidation Coal Company was formed in 1875 by the merger of the Iowa Central Coal Company, the Black Diamond Mines of Coalfield, in Monroe County, Iowa, and the Eureka Mine, in Beacon, Iowa. By 1878, Consolidation Coal Company had 400 employees, and in 1880, it was purchased by the Chicago and North Western Railway.[5]

The coal camp at Muchakinock was about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of Oskaloosa 41°13′20.03″N 92°38′25.86″W / 41.2222306°N 92.6405167°W[6] quickly grew into one of the most prosperous and largest coal camps in Iowa.[7] Consolidation Mine No. 1 was opened in 1873.

In 1880, there was a labor dispute in Muchakinock, and J. E. Buxton, Consolidation's superintendent, sent Major Thomas Shumate south to hire hire African Americans as strike breakers. Shumate hired "lots of crowds" of "colored men" from Virginia. Whole families arrived with each "crowd". "Bringing these men to the mines, and the employment of colored miners was a new thing". The first "crowd" arrived in Muchakinock on March 5, 1880. By October 6, 1880 Shumate had brought in six "crowds". The "third crowd" filled one railroad passenger car. It left Staunton, Virginia on May 12 and traveled via Chicago and Marshalltown, Iowa, arriving in Muchakinock on May 15. Rail fare from Virginia to Iowa was $12, taken as an advance against each miner's monthly wages.[4] The new African American employees proved so satisfactory that they were retained, and in years to come, much of the wealth of the company was attributed to their labor.[8]

In 1884, the Chicago and Northwestern completed a 64-mile (103 km) branch from Belle Plaine to Muchakinock.[9] By then, Mines 1, 2, 3 and 5 were in operation in Muchakinock. No. 6 was a shaft mine, newly opened just north of the camp.[10]

By 1887, the African American workers in Muchakinock had organized a mutual protection society. Members paid fifty cents a month, or $1 per family. 80% of this paid for health insurance, while the remainder went into a sinking fund to cover members' burial expenses. The coal company acted as banker to this society.[11]

By 1893, Consolidation Mines No. 6 and 7, located about 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Oskaloosa, produced 1550 tons of coal per day, employing 489 men and boys. No. 6 had a 130-foot (40 m) shaft, while No. 7 had a 45-foot (14 m) shaft. Both mines worked the same 6-foot-thick (1.8 m) coal seam, using the double-entry room and pillar system of mining.[12]

Mine No. 8 was three miles (5 km) northwest of Muchakinock.

The Bituminous Coal Miners' Strike of 1894 lasted from late April through May of that year. All of Iowa's coal miners went on strike, with the exception of the miners at Muchakinock and Evans (8 miles north along Muchakinock Creek). Tensions were high enough that the company management armed Muchakinock's black miners with Springfield rifles. By May 28, tension was so high that Companies G and K of the Second Regiment of the Iowa National Guard were sent to Muchakinock to preserve order. On May 30, large bodies of armed strikers, from 400 to 600 men, were congregating in Mahaska County, apparently intent on forcing the nearby mining camp of Evans to strike as the first stage of an attack on Muchakinock. In the end, no shots were fired.[13][14][15]

African Americans headed numerous institutions in Muchakinock. There was a "colored" Baptist church in town, under Rev. T. L. Griffith.[16] Samuel J. Brown, the first African American to receive a bachelor's degree from the State University of Iowa, was principal of the Muchakinock public school.[17][18] B. F. Cooper was noted as one of only two "colored" pharmacists in the state.[19]

Muchakinock reached a peak population of about 2,500, but by 1900, the coal of the Muchakinock valley was largely exhausted, and the Consolidation Coal Company opened a new mining camp in Buxton. The founding of Buxton in 1901 led to a "great exodus," leaving the town nearly vacant by 1904. Today, acid mine drainage and red piles of shale are all that remain of the mines along Muchakinock Creek.[20]

Buxton

As early as 1888, a few small mines were in operation along Bluff Creek, but this changed at the dawn of the 20th century. In 1900 and 1901, after extending the Muchakinock branch of the Chicago and North Western tracks across the Des Moines River, the Consolidation Coal Company opened a new mining camp at Buxton, in Monroe County 41°9′30″N 92°49′15.63″W / 41.15833°N 92.8210083°W. The camp was named by B. C. Buxton after his father, J. E. Buxton, who had managed the mines at Muchakinock.

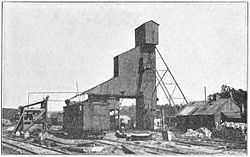

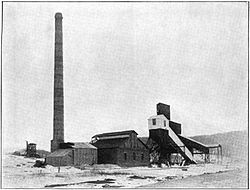

Consolidation Mine No. 10 was about 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Buxton, with a 119-foot-deep (36 m) shaft and a 69-foot (21 m) headframe, working a coal seam that varied from 4 to 7 feet (2.1 m) thick. The hoists could lift 4 cars to the surface in a minute, each carrying up to 1.5 tons of coal. Electric haulage was used in the mines, using a combination of third-rail, trolley wire, and rack-and-pinion haulage. Mine No. 11, opened in 1902, was about a mile south of No. 10, with a 207-foot (63 m) shaft. By 1908, Consolidation had opened Mine No. 15. All of the Buxton mines worked a coal seam about 54 inches thick.

In 1901, Consolidation's miners organized locals 1799 and 2106 of the United Mine Workers union, with memberships of 493 and 691 respectively. Local 2106 immediately became the largest union local in Iowa, in any trade.[21]. At that time, Consolidation's mines were described as being "worked almost entirely by colored miners."[22] In 1913, the Buxton UMWA union local was reported to have "at least 80 percent colored men".[23] With 1508 members, Local 1799 at Buxton was the largest UMWA local in the country.[24] The benevolent society established at Muchakinock continued in operation at Buxton, as the Buxton Mining Colony.[25]

Buxton was a classic company town; it was unincorporated, and the company was the sole landlord. In the words of one commentator, "Mr. Buxton ... has not attempted to build up a democracy. On the contrary he has built up an autocracy and he is the autocrat, albeit a benevolent one."[25] Booker T. Washington described justice in Buxton as being "administered in a rather summary frontier fashion" that reminded him "of the methods formerly employed in some of the frontier towns farther west."[26]

The Consolodation Coal Company took a paternal attitude towards the town. In 1908, the town covered approximately one square mile, with about 1000 houses, typically with 5 or 6 rooms each. Everything was owned by the coal company. Rental housing was only available to married couples, at a rate of $5.50 to $6.50 per month. Single men were not permitted, and families having any kind of disorder were evicted on 5 days' notice. The average wage in the mines was $3.63 per day in 1908, when the mines employed 1239 men. Monthly wages varied from $70.80 for day laborers, but about 100 men made over $140 per month.[25]

As in Muchakinock, African Americans held many leadership roles. The postmaster, superintendent of schools, most of the teachers, two justices of the peace, two constibles and two deputy sheriffs were African American. The Bank of Buxton, with deposits in 1907 of $106,796.38, had only one cashier, also African American, and one of the civil engineers working for the mining company was African American.[25][26] For a brief time between 1903 and 1905, The Buxton Eagle was Buxton's newspaper.[27] Edward A. Carter, MD, the first "colored" graduate of the University of Iowa College of Medicine, came to Buxton as assistant physician to the Buxton Mining Colony, and went on to be company surgeon to the mining company as well as the Chicago and Northwestern Railway.[28][29]

Richard R. Wright Jr. wrote in 1908 that "The relations of the white minority to the black majority are most cordial. No case of assault by a black man on a white woman has ever been heard of in Buxton. Both races go to school together; both work in the same mines, clerk in the same stores, and live side by side."[25] In the same year, Booker T. Washington wrote of Buxton as "a colony of some four or five thousand Colored people ... to a large extent, a self-governing colony, but it is a success." He recommended a study of Buxton to a textile manufacturer interested in raising capital for a cotton mill employing black labor.[30]

By 1908, as mines 11 and 13 were almost exhausted, the population of Buxton was about 5000. Unlike smaller company towns where miners usually lived within walking distance of the mines, Buxton's mines were spread out over a considerable distance, so commuter trains were run to ferry the men to the mines.

The coal company gave the YMCA free use of a building, valued at $20,000.[31] The YMCA had a reading room and library, gym, baths, kitchen, dining room, and a meeting hall available for use of labor unions and lodges.[32] The Buxton YMCA drew "the color line" and did "not allow white men in the membership," although they were "allowed to attend the entertainments, a privilege freely used."[33] The Buxton YMCA offered a variety of adult education programs, including literacy and hygiene classes, as well as a variety of public lectures. The YMCA also controlled the Opera House, keeping out "objectionable and immoral shows."[34]

As is typical of mining company towns, there was a company store, the Monroe Mercantile Company. This was a big operation, with 72 employees, some paid as much as $68 per month, and many of them African Americans. There were also barber shops, a tailor shop, a butcher shop, and a hotel, all run by African Americans.[25]

In 1919, Mine No. 18 at Buxton was the most productive coal mine in Iowa. This mine employed 498 men year round, producing almost 300,000 tons in that year, which was over 5% of the total production for the state.[35] The remains of Mine No. 18 were dynamited in 1944.[36]

In 1938, the Federal Writers Project Guide to Iowa reported that the site of Buxton was abandoned and that the locations of Buxton's former "stores, churches and schoolhouses are marked only by stakes." Every September, hundreds of former Buxton residents met on the former town's site for a reunion.[37]

The abandoned Buxton town was the subject of archaeological survey in the 1980s which investigated the economic and social aspects of material culture of African Americans in Iowa.[38]

References

- ^ Greg A. Brick, Iowa Underground, Trails Books, 2004; Chapter 42, page 143-144.

- ^ Monroe N. Work, ed., Negro Towns and Settlements in the United States, Negro Year Book 1914–1915 Negro Year Book Company, Tuskeegee Institute, 1914; page 298.

- ^ Fourth Biennial Report of the State Mine Inspectors to the Governor of the State of Iowa for the Years 1888 and 1889 Ragsdale, Des Moines, 1889; see for example, page 73.

- ^ a b Report: Contested Election Case – J. C. Cook vs. M. E. Cutts, United States Congressional Serial Set, Section III, Washington, DC, Feb. 19, 1883.

- ^ James H. Lees, History of Coal Mining in Iowa, Chapter III of Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, 1908, Des Moines, 1909; page 666-558

- ^ Topographical Map of Mahaska County, Iowa, Huebinger's Atlas of the State of Iowa, Iowa Publishing Co., 1904.

- ^ Iowa's Pioneer Coal Operators, Eighth Biennial Report of the State Mine Inspectors to the Governor of the State of Iowa for the Two Years Ending June 30, 1897, Conway, Des Moines, 1897; page 76.

- ^ Negro Governments in the North, The American Review of Reviews, XXXVIII, New York, Oct. 1908; page 472

- ^ Annual Report of the Chicago and Northwestern Railway Company for the Twenty-Sixth Fiscal Year Ending May 31, 1885

- ^ Second Biennial Report of the State Mine Inspector to the Governor of the State of Iowa for the Years 1884 and 1885; pages 38, 57.

- ^ Portrait and Biographical Album of Mahaska County, Chapman Brothers, Chicago, 1887; pages 522–523

- ^ John W. Canty, Biennial Report of the Second District, Sixth Biennial Report of the State Mine Inspectors to the Governor of the State of Iowa for the Two Years Ending June 30, 1893, Ragsdale, Des Moines, 1893; pages 50–51

- ^ Thomas J. Hudson, Iowa Chapter VIII, Events from Jackson to Cummins, The Province and the States, Vol. V, the Western Historical Association, 1904; page 170

- ^ The Natioinal Guard – Iowa's Splendid Militia, The Midland Monthly, Vol. II, No. 5 Nov. 1894; page 419.

- ^ Service at Muchakinock and Evans, in Mahaska County, During the Coal Miners' Strike, Report of the Ajutant-General to the Governor of the State of Iowa for Biennial Period Ending Nov. 30, 1895, Conway, Des Moines, 1895; page 18

- ^ T. L. Griffith, The Colored Baptists of Iowa, The Baptist Home Mission Monthly, Vol. XXI, No. 7, July 1899, page 286.

- ^ Who's Who of the Colored Race, Frank L. Mather, Chicago, 1915; page 45.

- ^ Robert B. Slater, The First Black Graduates of the Nation's 50 Flagship State Universities, The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, No. 13 (Autumn, 1996); pages 72–85

- ^ Two Colored Pharmacists, American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record, Vol. XXX, No 12, June 25, 1897; page 357

- ^ Muchakinock Creek – Improving water quality for the future, Iowa Department of Natural Resources, 2005; page 3.

- ^ Trade Unions in Iowa – Table No. 1, Mine Workers of America, United, Tenth Biennial Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the State of Iowa, 1901–1902, Murphy, Des Moines, 1903; page 232.

- ^ James H. Lees, History of Coal Mining in Iowa, Chapter III of Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, 1908, Des Moines, 1909; pages 549–550.

- ^ Booker T. Washington, The Negro and the Labor Unions, The Atlantic Monthly (June 1913); page 761.

- ^ Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Convention of the United Mine Workers of America Jan. 16 – Feb. 2, 1912, Indianapolis; page 78A. Note: Only 3 other locals had over 1000 members.

- ^ a b c d e f Richard R. Wright, Jr., The Economic Conditions of Negroes in the North – IV Negro Governments in the North, Southern Workman, Vol. XXXVII, No. 9 (Sept. 1908); pages 494–498.

- ^ a b Booker, T, Washington, Chapter VIII: The Negro as Town-Builder, The Negro in Business, Hertel, Jenkins & Co, 1907;pages 76–77.

- ^ About this Newspaper: The Buxton Eagle Library of Congress Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers web site.

- ^ Men of the Month: A Busy Physician, The Crisis, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Aug. 1914); page 170

- ^ Edward A. Carter, Letter, The Iowa Alumnus, Vol. XIII, No. 1 (October 1915); page 48.

- ^ Booker T. Washington, letter to Fredrick Barrett Gordon, May 17, 1909, The Booker T. Washington Papers, Vol. 10, University of Illinois Press, 1981; page 108.

- ^ Henry Hinds, The Coal Deposits of Iowa, Iowa Geological Survey Annual Report, 1908, Des Moines, 1909; page 232.

- ^ Gives Building to YMCA – Coal company at Buxton, Iowa, helps association work among its colored employees New York times, Dec. 14, 1903.

- ^ In the World of Labor, Association Men Vol. XXXV, No. 3 (Dec. 1909); page 104.

- ^ Notes on Progress and Service, Association Men, Vol. XXXVI, No. 9 (June 1911); page 407.

- ^ H. E. Pride, Iowa Coal, Bulletin No. 48, Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts Engineering Extension Department, Oct. 6, 1920.

- ^ Greg A. Brick, Iowa Underground, Trails Books, 2004; Chapter 42, page 144.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project, The WPA Guide to 1930's Iowa, Viking Press, 1938, reprinted by the University of Iowa Press, 1986; page 81.

- ^ Gradwohl, David M., and Nancy M. Osborn (1984) Exploring Buried Buxton. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa.

External links

Categories:- Coal companies of the United States

- Mahaska County, Iowa

- Monroe County, Iowa

- Chicago and North Western Railway

- Labor disputes in the United States

- Miners' labor disputes

- African American history

- Company towns in Iowa

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.