- Caesar's Comet

-

Caesar's Comet[1] (scientific designation C/-43 K1) – also known as Comet Caesar and the Great Comet of 44 BC – was perhaps the most famous comet of antiquity. The seven day visitation was taken by Romans as a sign of the deification of the recently dead dictator, Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE).[2]

Caesar's Comet was one of only five comets known to have had a negative absolute magnitude and was possibly the brightest daylight comet in recorded history.[3] It was not periodic and may have disintegrated.

Contents

History

Caesar's Comet was known to ancient writers as the Sidus Iulium ("Julian Star") or Caesaris astrum ("Star of Caesar"). The bright, daylight-visible comet appeared suddenly during the festival known as the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris – for which the 44 BC iteration was long considered to have been held in the month of September (a conclusion drawn by Sir Edmund Halley). The dating has recently been revised to a July occurrence in the same year, some four months after the assassination of Julius Caesar, as well as Caesar's own birth month. According to Suetonius, as celebrations were getting underway, "a comet shone for seven successive days, rising about the eleventh hour, and was believed to be the soul of Caesar."[4]

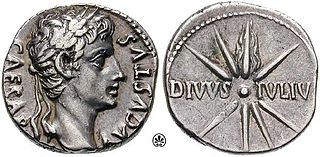

The Comet became a powerful symbol in the political propaganda that launched the career of Caesar's great-nephew (and adoptive son) Augustus. The Temple of Divus Iulius (Temple of the Deified Julius) was built (42 BC) and dedicated (29 BC) by Augustus for purposes of fostering a "cult of the comet". (It was also known as the "Temple of the Comet Star".[5]) At the back of the temple a huge image of Caesar was erected and, according to Ovid, a flaming comet was affixed to its forehead:

To make that soul a star that burns forever

Above the Forum and the gates of Rome.[6]Modern scholarship

In 1997, two scholars at the University of Illinois at Chicago – John T. Ramsey (a classicist) and A. Lewis Licht (a physicist) – published a book [7] comparing astronomical/astrological evidence from both Han China and Rome. Their analysis, based on historical eye-witness accounts, Chinese astronomical records, astrological literature from later antiquity and ice cores from Greenland glaciers, yielded a range of orbital parameters for the hypothetical object. They settled on a 0.224 A.U. orbit for the object which was apparently visible with a tail from the Chinese capital (in late May) and as a star-like object from Rome (in late July).

A few scholars, such as Robert Gurval of UCLA and Brian G. Marsden of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, leave the comet's very existence as an open question. Marsden notes in his forward to Ramsey and Licht's book, "Given the circumstance of a single reporter two decades after the event, I should be remiss if I were not to consider this [i.e., the comet's non-existence] as a serious possibility." [8]

In literature

Ovid describes the deification of Caesar in Metamorphoses (8 AD):

Then Jupiter, the Father, spoke..."Take up Caesar’s spirit from his murdered corpse, and change it into a star, so that the deified Julius may always look down from his high temple on our Capitol and forum." He had barely finished, when gentle Venus stood in the midst of the Senate, seen by no one, and took up the newly freed spirit of her Caesar from his body, and preventing it from vanishing into the air, carried it towards the glorious stars. As she carried it, she felt it glow and take fire, and loosed it from her breast: it climbed higher than the moon, and drawing behind it a fiery tail, shone as a star.[9]

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (1599), Caesar's wife remarks on the fateful morning of her husband's murder: "When beggars die there are no comets seen. The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes."

References

- ^ Ramsey, John T. and A. Lewis Licht (1997), The Comet of 44 BC and Caesar's Funeral Games, Scholars Press (Series: APA American Classical Studies, No. 39.)

- ^ Grant, Michael (1970), The Roman Forum, London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson; Photos by Werner Forman, pg 94.

- ^ Flare-up on July 23–25, 44 BC (Rome): −4.0 (Richter model) and −9.0 (41P/Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresák model); absolute magnitude on May 26, 44 BC (China): −3.3 (Richter) and −4.4 (41P/TGK); calculated in Ramsey and Licht, Op. cit., pg 236.

- ^ Suetonius, Divus Julius; 88

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 2.93-94.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses; XV, 840.

- ^ Ramsey and Licht, Op. cit.

- ^ Marsden, Brian G., "Forward"; In: Ramsey and Licht, Op. cit.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses; XV; 745-842.

See also

Categories:- Comets

- Julius Caesar

- Augustus

- History of astrology

- 44 BC

- Comet stubs

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.