- Collapse of the Northern Cod Fishery

-

Main article: Cod fisheries

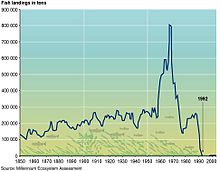

In 1992 the Canadian government declared a moratorium on the Northern Cod fishery that, for the past 500 years, had largely shaped the lives and communities of Canada’s eastern coast. The interplay between fishing societies and the resources on which they depend is palpable to even the most unacquainted observer: fisheries transform the ecosystem, which in turn pushes the fishery and society to adapt.[1] In the summer of 1992, when the Northern Cod biomass fell to one percent of its earlier level[2], it became apparent to Canada’s federal government that this relationship had been pushed to the breaking point and a moratorium was declared, ending the region’s half-millennium run with the Northern Cod.

Contents

Introduction

The collapse of the Northern Cod fishery marked a profound change in the ecological, economic and socio-cultural structure of Atlantic Canada. The change was expressed most acutely in Newfoundland, whose continental shelf lay under the region most heavily fished, and whose communities represented the vast majority of those who lost employment as a result of the moratorium.[3] Considering the importance of the cod fishery to the livelihood of Canada’s coastal communities, as well as the Northern Cod’s initial abundance in the region,[4] the fact that the fishery was mismanaged to the extent of collapse – from which to this day it has not recovered – is nothing short of shocking.

In an attempt to make sense of a blunder of such large proportion, academics have highlighted the following three contributing factors in the eventual collapse of the cod fishery:

Technological

A major factor that contributed to the depletion of the cod stocks off the shores of Newfoundland included the introduction and proliferation of equipment and technology that increased the volume of landed fish. For centuries local fishermen used technology that limited the volume of their catch, the area they fished, and allowed them to target specific species and ages of fish.[5] From the 1950s onwards, as was common in all industries at the time, new technology was introduced that allowed fishermen to trawl a larger area, fish to a deeper depth and for a longer time. By the 1960s, powerful trawlers equipped with radar, electronic navigation systems and sonar allowed crews to pursue fish with unparalleled success, and Canadian catches peaked in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[6] These new technologies adversely affected the Northern Cod population in two important ways: by increasing the area and depth that was fished, the cod were being depleted to the point that the surviving fish were incapable of replenishing the stock lost each year;[7] and secondly, the trawlers caught enormous amounts of non-commercial fish, which although economically unimportant, held huge ecological significance: incidental catch undermines the functioning of the ecosystem as a whole, depleting stocks of important predator and prey species. In the case of the Northern Cod, significant amounts of capelin – an important prey species for the cod – were caught as bycatch, further undermining the survival of the remaining cod stock.

Ecological uncertainty

Another factor important to consider in the understanding of the fishery’s collapse is the uncertainty inherent in the assessment of the cod as a resource. Management of a resource is an extremely complex task, with a multitude of interests, perspectives, and sources of information to take into account; when knowledge regarding the resource is limited, or clouded by imprecision, the task of managing it becomes even more difficult. The management of fisheries are associated with an especially high degree of uncertainty due to problems inherent in the nature of the resource. Newfoundland’s cod fisheries were no exception: an imperfect understanding of the ocean ecosystem; technical and environmental challenges associated with observation techniques, which led to incomplete data on the resource (the cod); and the naturally high levels of variability in the population due to dynamic environmental factors (such as ocean temperature) combined to make the discernment of the effects of exploitation an arduous task.[8] Unfortunately, this led to predictions about the condition and future of the cod stock that were mired in uncertainty, making it more difficult for the government to choose the appropriate course of action.

Socioeconomic

In addition to ecological considerations, decisions regarding the future of the fisheries were also influenced by social and economic factors. Throughout Atlantic Canada, however most pronounced in Newfoundland, the cod fishery was a source of social and cultural identity.[9] For many families, it also represented their livelihood: most families were connected either directly or indirectly with the fishery as fishers, fish plant workers, fish sellers, fish transporters, or as employees in related businesses.[10] Additionally, many companies, both foreign and domestic, as well as individuals, had invested heavily in the boats, equipment and the infrastructure of the fishery, and therefore felt it was in their best interest to maintain an open-access policy to the ocean and its resources. What this alludes to is the unfortunate paradox that often accompanies open-access resources and is known by most as the Tragedy of the Commons: what is in the individual's best interest is not always in the best interest of a society at whole. In the case of Newfoundland and the Northern Cod fishery this meant that from the perspective of the individual participating in the fishing industry, maximizing their catch was in their best interest; however when the government failed to intervene – due largely to the highly sensitive nature of the political discourse created by the expansive group of stakeholders – the ecosystem was brought past its threshold and collapsed, leaving everyone worse-off.

When the government was finally galvanized to action, it was too late. The 1992 moratorium was initially meant to last two years, with the hopes that the Northern Cod population would recover, and along with it, the fishery. Unfortunately, the damage done to Newfoundland’s coastal ecosystem was indelible, and even after sixteen years, the Northern Cod population has failed to rebound[11] and the Cod Fishery remains closed.

The impact of the collapse on Newfoundland

The moratorium in 1992 marked the largest industrial closure in Canadian history.[12] In Newfoundland alone, over 35,000 fishers and plant workers from over 400 coastal communities became unemployed.[13] In response to dire warnings of social and economic consequences, the federal government intervened, initially providing income assistance through the Northern Cod Adjustment and Recovery Program, and later through the Atlantic Groundfish Strategy, which included money specifically for the retraining of those workers displaced by the closing of the fishery.[14] Newfoundland has since experienced a dramatic environmental, industrial, economic, and social restructuring, including considerable outmigration,[15] but also increased economic diversification, an increased emphasis on education, and the emergence of a thriving invertebrates fishing industry (as the predatory groundfish population declined, snow crab and northern shrimp proliferated, providing the basis for a new industry that is roughly equivalent in economic value as the cod fishery it replaced).[16]

Notes

- ^ Hamilton et al., 195.

- ^ Hamilton and Butler, 1.

- ^ Gien, 121.

- ^ Hutchings, 943.

- ^ Keating, 1.

- ^ Hamilton et al., 200.

- ^ Hamilton et al., 199.

- ^ Cochrane, 6.

- ^ Gien, 121.

- ^ Gien, 121.

- ^ Hamilton et al., 196.

- ^ Dolan, 202.

- ^ Gien, 121.

- ^ Hamilton and Butler, 2.

- ^ Kennedy, 315.

- ^ Hamilton and Butler, 2.

References

- Cochrane, Kevern. “Reconciling Sustainability, Economic Efficiency and Equity in Fisheries: the One that Got Away.” Fish and Fisheries 1 (2000): 3-21.

- Dayton, Paul, et al. “Environmental Effects of Marine Fishing.” Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 5 (1995): 205-232.

- Dolan, Holly, et al. “Restructuring and Health in Canadian Coastal Communities.” EcoHealth 2 (2005): 195-208.

- Gien, Lan. “Land and Sea Connection: The East Coast Fishery Closure, Unemployment and Health.” Canadian Journal of Public Health 91.2 (2000): 121-124.

- Hamilton, Lawrence, and Melissa J. Butler. “Outport Adaptations: Social Indicators through Newfoundland’s Cod Crisis.” Human Ecology Review 8.2 (2001): 1-11.

- Hamilton, Lawrence, et al. “Above and Below the Water: Social/Ecological Transformation in Northwest Newfoundland.” Population and Environment 25.3 (2004): 195-215.

- Hutchings, Jeffrey. “Spatial and Temporal Variation in the Density of Northern Cod a Review of Hypotheses for the Stock’s Collapse.” Canadian Journal of Aquatic Science 53 (1996): 943-962.

- Keating, Michael. “Media, fish and Sustainability.” National Round Table on Environment and Economy February (1994).

- Kennedy, John. “At the Crossroads: Newfoundland and Labrador Communities in a Changing International Context.” The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 34.3 (1997): 297-318.

Categories:- Fisheries

- Fishing in Canada

- Environmental disasters in Canada

- Atlantic Canada

- History of Newfoundland and Labrador

- History of Canada (1982–1992)

- Economic history of Canada

- 1992 in economics

- 1992 in Canada

- Environmental issues with fishing

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.