- Cincinnati Riots of 1841

-

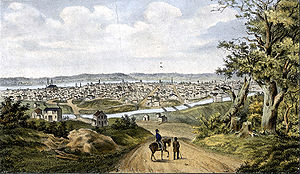

A view of Cincinnati, Ohio in 1841 from one of the surrounding hills to the north. In the foreground is the Miami and Erie Canal, and in the distance is the Ohio River and Kentucky.

A view of Cincinnati, Ohio in 1841 from one of the surrounding hills to the north. In the foreground is the Miami and Erie Canal, and in the distance is the Ohio River and Kentucky.

The Cincinnati Riots of 1841 occurred after a long drought had created widespread unemployment in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. Over a period of several days in September 1841, unemployed whites attacked the blacks, who fought back. Many blacks were rounded up and held behind a cordon, then moved to the jail. According to the authorities, this was for their own protection.[1]

Contents

Background

By 1840, Cincinnati had grown from a frontier settlement to the 6th largest city in the USA. It was a city of contrasts, with prosperous neighborhoods and squalid, violent slums. Many of the businessmen who controlled the city were interested in good relationships with the slave-owning states to the south of the Ohio River, and were hostile to abolitionists and blacks. The Ohio constitution denied blacks the franchise, and the Black Laws imposed further restrictions. Black children were denied education in the public schools, although black propertyholders had to pay taxes to support these schools. Black immigrants to the state had to register and provide surety. A black could not serve on a jury, testify in legal cases involving a white person or serve in the militia. However, drawn by the economic opportunities, the black population had grown from 690 in 1826 to an official count of 2,240 out of a total of 44,000 citizens by 1840. Many of the blacks had jobs as craftsmen or tradesmen, earning good wages for the time. Many owned property.[2]

Build-up

On 1 August 1841, the black leaders held ceremonies to commemorate the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies, an action viewed with hostility by many whites. That month the city experienced a drought and heatwave which caused the Ohio River to drop to the lowest waterline yet recorded, throwing many who depended on the river traffic out of work. Tensions mounted, with several scuffles between blacks and whites.[2]

On the evening of Tuesday, 31 August, a group of Irishmen got into a fight with some blacks. On Wednesday, the fight resumed. A mob of white men armed with clubs attacked the occupants of a Negro boarding house. The brawl spread to involve the occupants of neighboring houses and lasted for about three quarters of an hour. Although several people were wounded on both sides, the incident was not reported to the police and no arrests were made. Another encounter took place on the Thursday, where two white boys were badly injured, apparently with knives.[3] That day, bands of angry whites were roaming the city. An eyewitness said blacks were "assaulted wherever found in the streets, and with such weapons and violence as to cause death".[4]

Friday 3 September

On the Friday, there were rumors that more serious disturbances were planned. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette, which published a full report of the riots, did not hear of any special police precautions to prevent trouble.[3] According to John Mercer Langston, a child of twelve living in the area who later had a distinguished political career, the black elders armed themselves with guns, planned their defence against attack, and elected a mulatto named Major J. Wilkerson as their leader.[2] Wilkerson had been born a slave in Virginia in 1813, and had purchased his freedom. He had become an elder of the AME Church in Cincinnati. Langston call him a "champion of his people's cause" who would "maintain his own rights as well as those of the people he led". Wilkerson ensured that the women and children were moved to safe places, then deployed the men in defensive positions on roofs, in alleys and behind buildings.[4]

A mob organized by people from Kentucky assembled in Fifth Street Market, armed with clubs and stones. They marched towards Broadway and Sixth streets, where they wrecked a black-owned confectionary house on Broadway, next to Sycamore. The crowd grew, and ignored calls to disperse from local dignitaries, including the mayor.[3] Advancing to attack the black neighborhood, the mob was met with gunfire and retreated. In several further attacks, people on both sides were wounded and some reported killed. Around one in the morning, a group of whites brought up an iron six-pounder cannon from near the river, which they loaded with boiler punchings and pointed down Sixth street from Broadway. By this time many of the blacks had fled, but fighting continued, with the cannon being fired several times.[3]

About two o'clock, militiamen arrived and managed to end the fighting. The soldiers threw a cordon around several blocks of the black neighborhood, holding those within captive. The militia also rounded up other blacks in the city and marched them to the cordoned-off area, where they were also held captive until they paid bond.[4]

Saturday 4 September

Mayor Samuel W. Davies called a public meeting at the Court House on Saturday morning to discuss how to prevent further violence. The meeting resolved to find and arrest the blacks who had injured the two white boys.[3] The group blamed the black community for the violence. While strongly condemning abolitionists, they vowed not to tolerate mob violence. The authorities promised to take action to drive out undesitable blacks from the city, saying they would enforce the black law of 1807 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. They would protect African Americans and their property until they either gave bond or left the city. Black leaders met in Bethel AME church and made assurances to the mayor that they would remain calm, suppress violations of law and order and refrain from bearing arms.[4] At a special session of the City Council, measures were passed to enlist ordinary citizens, officers, watchmen and firemen to help preserve the peace, authorizing the mayor to increase the number of his deputies up to five hundred, and calling for the county militia to be deployed.[3]

The militia and temporary policemen (some of whom may have been rioters) deployed throughout the city with orders to arrest every black man they found. Some of the blacks had fled the city to Walnut Hills to the north of the city and others went into hiding, but about 300 were rounded up and thrown into jail. A mob followed the prisoners to jail, taunting them, and extra guards had to be brought in to defend the prisoners. According to the newspapers, Kentuckians were free to visit the jail to look for runaway slaves.[4]

Despite the resolutions and actions, it was found that the mob planned to resume their attacks on Saturday after nightfall. The Mayor deployed peacekeeping forces including the military, firemen, citizens acting as assistants of the Marshal, a troop of horse and several companies of voluntary infantry. The mob organized themselves and divided to attack at different points. They broke into the building that held the press of the Philanthropist, breaking up the press and carrying it to the river, where they threw it into the water. They broke into and wrecked several black-owned houses, shops and a church, before finally dispersing around dawn on the Sunday. The authorities managed to arrest and secure about forty of the mob.[3]

Reactions

The editor of the Cincinnati Daily Gazette said that the riot could have been checked in its early phases. "A determined corps of fifty or one hundred men would have dispersed the crowd". According to Langston, the mob was "the blackest and most detestable moment in Cincinnati's history". In reaction to the riots, the black community established several self-help organizations over the next few years including the United Colored Association, the Sons of Enterprise and the Sons of Liberty.[4]

References

- ^ "Timeline of Civil Rights Conflict in SW Ohio". Safe Passage. Greater Cincinnati Television Educational Foundation. http://www.safepassageohio.org/civilrights/timeline.asp. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ a b c Henry Louis Taylor (1993). "John Mercer Langston and the Cincinnati Riot of 1841". Race and the city: work, community, and protest in Cincinnati, 1820-1970. University of Illinois Press. p. 29ff. ISBN 0252019865. http://books.google.ca/books?id=9l_e3Adl7n0C&pg=PA29.

- ^ a b c d e f g "RIOT AND MOBS, CONFUSION AND BLOOD SHED". Cincinnati Daily Gazette. September 6, 1841. http://www.cincinnatilibrary.org/tallstacks/voices/newspaper-riot.html. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Nikki Marie Taylor (2005). Frontiers of freedom: Cincinnati's Black community, 1802-1868. Ohio University Press. p. 199ff. ISBN 0821415794. http://books.google.ca/books?id=ZC8xDzjUM-cC&pg=PA119. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

Cincinnati riots 1829 Attack on blacks • 1836 Attack on abolitionist press • 1841 Attack on blacks • 1853 Papal envoy visit • 1855 Attack on Germans • 1884 Rigged jury dispute • 1967 Disputed murder conviction • 1968 Martin Luther King assassination • 2001 Police shooting of suspectCategories:- 1841 in Ohio

- White American riots in the United States

- History of Cincinnati, Ohio

- 1841 riots

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.