- The Blair Witch Project

-

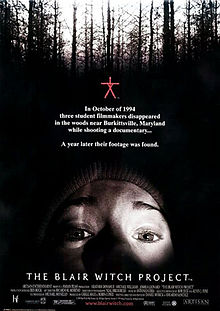

Theatrical release posterDirected by Daniel Myrick

Eduardo SánchezProduced by Robin Cowie

Gregg HaleWritten by Daniel Myrick

Eduardo SánchezStarring Heather Donahue

Joshua Leonard

Michael C. WilliamsMusic by Antonio Cora Cinematography Neal Fredericks Editing by Daniel Myrick

Eduardo SánchezStudio Haxan Films Distributed by Artisan Entertainment Release date(s) July 30, 1999 Running time 82 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $20,000–$750,000 Box office $248,639,099 The Blair Witch Project is a 1999 American horror film pieced together from amateur footage. The film was produced by the Haxan Films production company. The film relates the story of three student filmmakers (Heather Donahue, Joshua Leonard, and Michael C. Williams) who hiked into the Black Hills near Burkittsville, Maryland in 1994 to film a documentary about a local legend known as the Blair Witch, and disappeared. The viewers are told that the three were never seen or heard from again, although their video and sound equipment (along with most of the footage they shot) was discovered a year later. This "recovered footage" is presented as the film the viewer is watching.[1]

A studio production film based on the theme of The Blair Witch Project was released on October 27, 2000 titled Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2. Another sequel was planned for the following year, but did not materialize. On September 2, 2009, it was announced that co-directors Eduardo Sanchez and Daniel Myrick were pitching the sequel.[2]

Contents

Plot

In October 1994, film students Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams and Joshua Leonard set out to produce a documentary about the fabled Blair Witch. They travel to Burkittsville, Maryland, formerly Blair, and interview locals about the legend of the Blair Witch. The locals tell them of Rustin Parr, a hermit who kidnapped seven children in the 1940s and brought them to his house in the woods, where he tortured and murdered them. Parr brought the children into his home's basement in pairs. Parr forced the first child to face the corner and listen to their companion's screams as he murdered the second child. Parr would then murder the first child. Eventually turning himself in to the police, Parr later pleaded insanity, saying that the spirit of Elly Kedward, a witch hanged in the 18th century, had been terrorizing him for some time and promised to leave him alone if he murdered the children. The trio also interviews Mary Brown, a local eccentric who tells them that she had encountered the Blair Witch as a child.

The second day, the students begin to explore the woods in north Burkittsville to look for evidence of the Blair Witch. Along the way, a fisherman warns them that the woods are haunted, and recalls a time that he had seen strange mist rising from the water. The students hike to Coffin Rock, where five men were found ritualistically murdered in the 19th century, and then camp for the night. The next day they move deeper into the woods, despite being uncertain of their exact location on the map. They eventually locate what appears to be an old cemetery with seven small cairns. They set up camp nearby and then return to the cemetery after dark. Josh accidentally disturbs a cairn, and Heather hastily repairs it. Later, they hear crackling sounds in the darkness that seem to be coming from all directions and assume the noises are from animals or locals following them.

The following day they attempt to return to their vehicle, but cannot find their way; they try until nightfall, when they are forced to set camp. That night, they again hear crackling noises, but cannot see anything. The next morning they find three cairns have been built around their tent during the night. As they continue trying to find their way out of the woods, Heather realizes that her map is missing, and Mike later reveals that he kicked it into a creek out of frustration the previous day. Josh and Heather attack Mike in a fit of intense rage. They then realize they are now hopelessly lost, and decide to simply "head south". Soon, they discover a multitude of humanoid stick figures suspended from trees. That night, they hear more strange noises, including the sounds of children and bizarre "morphing" sounds. When an unknown force shakes the tent, they flee in a panic and hide in the woods until dawn. Upon returning to their tent, they find that their possessions have been rifled through, and Josh's equipment is covered with slime, causing them to question why only his belongings were affected. As the day wears on, they pass a log over a stream that was identical to the one they had passed earlier, despite having traveled directly south all day, and again set camp, completely demoralized at having wasted the entire day seemingly going in circles.

The next morning, Josh has disappeared. After trying in vain to find him, Mike and Heather eventually break camp and slowly move on. That night, they hear Josh screaming in the darkness, but are not able to find him. The next morning, Heather finds a bundle of sticks and fabric outside their tent. Later inspection reveals it contains blood-soaked scraps of Josh's shirt, as well as teeth and hair, but she does not mention this to Mike.

That night, Heather films herself apologizing to the co-producers of her project as well as her family, and breaks down crying, terrified that something terrible is hunting them. Later, they again hear Josh's agonized cries for help, but this time they follow them and discover a derelict abandoned house in the woods. Hanging on the front of the house is the same human stick figure that they saw in the woods. Mike races upstairs, following the voice, while Heather tries to follow. Mike then claims he hears Josh in the basement. He follows the sound and, after what seems to be a struggle, goes silent and drops to the floor. Heather runs down to the basement screaming for Mike, but gets no answer. She then enters the basement looking for both men, and her camera catches a glimpse of Mike facing the wall. Heather then screams as she and her camera drop to the floor. There is only silence as the footage ends.

Production

Development

The Blair Witch Project was developed in 1994[3] by the filmmakers. The script began with a 68 page outline, with the dialogue to be improvised.[3] Accordingly, the directors advertised in Back Stage magazine for actors with strong improvisational abilities.[4] There was a very informal improvisational audition process to narrow the pool of 2,000 actors.[5][6] In developing the mythology behind the movie, the filmmakers used many inspirations. Several character names are near-anagrams; Elly Kedward (The Blair Witch) is Edward Kelley, a 16th century mystic. Rustin Parr, the fictional 1940s child-murderer, began as an anagram for Rasputin.[7] In talks with investors, they presented an eight-minute documentary along with newspapers and news footage.[8] This documentary, originally called The Blair Witch Project: The Story of Black Hills Disappearances was produced by Haxan Films.

Filming

Filming began in October 1998 and lasted eight days.[4][9] Most of the movie was filmed in tiny Seneca Creek State Park in Montgomery County, Maryland, although a few scenes were filmed in the real town of Burkittsville.[10] Some of the townspeople interviewed in the film were not actors, and some were planted actors, unknown to the main cast. Donahue had never operated a camera before, and spent two days in a "crash course". Donahue said she modeled her character after a director she once worked with, citing the character's self assuredness when everything went as planned, and confusion during crisis.[11]

During filming, the actors were given clues as to their next location through messages given in milk crates found with Global Positioning Satellite systems. They were given individual instructions that they would use to help improvise the action of the day.[4] Teeth were obtained from a Maryland dentist for use as human remains in the film.[4] Influenced by producer Gregg Hale's memories of his military training, in which "enemy soldiers" would hunt a trainee through wild terrain for three days, the directors moved the characters far during the day, harassing them by night and depriving them of food.[8]

Almost 19 hours of usable footage was recorded which had to be edited down to 90 minutes.[6] The editing in post production took more than eight months. Originally it was hoped that the movie would make it on to cable television, and the filmmakers did not anticipate wide release.[3] The initial investment by the three University of Central Florida filmmakers was about US$35,000. Artisan acquired the film for US$1.1 million but spent US$25 million to market it.[12] The actors signed a "small" agreement to receive some of the profits from the film's release.[13]

Budget

A list of production budget figures have circulated over the years, appearing as low as $20,000. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Sánchez revealed that when principal photography first wrapped, approximately $20,000 to $25,000 had been spent.[14] Other figures list a final budget ranging between $500,000 and $750,000.[15]

Release

The Blair Witch Project was shown at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival, and released by Artisan on 30 July 1999 after months of publicity, including a ground-breaking campaign by the studio to use the Internet and suggest that the film was a record of real events. The distribution strategy for The Blair Witch Project was created and implemented by Artisan studio executive Steven Rothenberg.[16][17] The movie was positively received by critics and went on to gross over US$248 million worldwide,[18] making it one of the most successful independent films of all time. The DVD was released in December 1999 and presented only in fullscreen.

Reaction

The Blair Witch Project grossed $248,639,099 worldwide,[19] compared to its final budget, which ranged between $500,000 and $750,000.[15]

Rotten Tomatoes provides links to 127 reviews for the film, with 84% of these reviews being favorable.[20] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times gave the film four stars, calling it "an extraordinarily effective horror film".[21] It was listed on Filmcritic.com as the 50th best movie ending of all time.[22] Critics praised Donahue's apology to the camera near the end of the movie, saying it would cause "nightmares for years to come"; Roger Ebert compared this sequence to Robert Scott's final journal entries as he froze to death in the Antarctic.[21][23] Donahue has stated that there was a considerable backlash against her because of her association with the film, which she claims led to her having threatening encounters and difficulty obtaining employment.[24]

The Blair Witch Project is thought to be the first widely released film marketed primarily on the Internet.[25] A sequel, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, was released in the autumn of 2000, but was poorly received by most critics.[26] A third installment announced that same year did not materialize.[27]

The Blair Witch Project was given a Global Film Critics Award for Best Screenplay[28] and won the Independent Spirit John Cassavetes Award. Conversely, the film was nominated for the 1999 Razzie Award for Worst Picture. In 2008, Entertainment Weekly named The Blair Witch Project one of "the 100 best films from 1983 to 2008", ranking it at #99.[29] In 2006, Chicago Film Critics Association listed it as one of the "Top 100 Scariest Movies", ranking it #12.[30]

Cinematic and literary allusions

In the film, the Blair Witch is, according to legend, the ghost of Elly Kedward, a woman banished from the Blair Township (latter-day Burkittsville) for witchcraft in 1785. The directors incorporated that part of the legend, along with allusions to the Salem Witch Trials and The Crucible, to play on the themes of injustice done on those who were called witches.[5] They were influenced by The Shining, Alien and The Omen. Jaws was an influence as well, presumably because the witch was hidden from the viewer for the entirety of the film, forcing suspense from the unknown.[3]

Jim Knipfel of the New York Press has noted the similarities between Blair Witch and the widely-banned 1980 Italian cannibal film Cannibal Holocaust. In the first part of this film, a rescue team ventures into the jungles of South America to search for a missing group of filmmakers who previously traveled there to film a documentary about cannibalistic tribes. Their footage is eventually found and viewed, which makes up the second half of the film.[31]

Soundtrack

None of the songs featured on Josh's Blair Witch Mix actually appear in the movie. However "The Cellar" is played during the credits and the DVD menu. This collection of mostly goth rock and industrial tracks is supposedly from a mix tape made by ill-fated film student Joshua Leonard. In the story, the tape was found in his car after his disappearance. Some of the songs featured on the soundtrack were released after 1994, after the events of the movie supposedly have taken place. Several of them feature dialogue from the movie as well.

- "Gloomy Sunday" - Lydia Lunch

- "The Order of Death" - Public Image Ltd.

- "Draining Faces" - Skinny Puppy

- "Kingdom's Coming" - Bauhaus

- "Don't Go to Sleep Without Me" - The Creatures

- "God Is God" - Laibach

- "Beware" - The Afghan Whigs

- "Laughing Pain" - Front Line Assembly

- "Haunted" - Type O Negative

- "She's Unreal" - Meat Beat Manifesto

- "Movement of Fear" - Tones on Tail

- "The Cellar" - Antonio Cora

Media tie-ins

Books

In September 1999, D.A. Stern compiled The Blair Witch Project: A Dossier. Perpetuating the film's "true story" angle, the dossier consisted of fabricated police reports, pictures, interviews and newspaper articles presenting the movie's premise as fact, as well as further elaboration on the Elly Kedward and Rustin Parr legends (an additional "dossier" was created for Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2). Stern wrote the 2000 novel Blair Witch: The Secret Confessions of Rustin Parr and in 2004, revisited the franchise with the novel Blair Witch: Graveyard Shift, featuring all original characters and plot.

In May 1999, a Photonovel adaptation of The Blair Witch Project was written by Claire Forbes and was released by Fotonovel Publications.

The Blair Witch Files

A series of eight young adult books entitled The Blair Witch Files were released by Random subsidiary Bantam from 2000 to 2001. The books center on Cade Merill, a fictional cousin of Heather Donahue, who investigates phenomena related to the Blair Witch in attempt to discover what really happened to Heather, Mike and Josh.[32]

- Blair Witch Files 1 - The Witch's Daughter

- Blair Witch Files 2 - The Dark Room

- Blair Witch Files 3 - The Drowning Ghost

- Blair Witch Files 4 - Blood Nightmare

- Blair Witch Files 5 - The Death Card

- Blair Witch Files 6 - The Prisoner

- Blair Witch Files 7 - The Night Shifters

- Blair Witch Files 8 - The Obsession

Comic books

In August 1999, Oni Press released a one-shot comic promoting the film, simply titled The Blair Witch Project. Written by Jen Van Meter and drawn by Bernie Mireault, Guy Davis, and Tommy Lee Edwards, the comic featured three short stories elaborating on the mythology of the Blair Witch. In mid-2000, the same group worked on a four-issue series called The Blair Witch Chronicles.

In October 2000, coinciding with the release of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, Image Comics released a one-shot called Blair Witch: Dark Testaments, drawn by Charlie Adlard and written by Ian Edginton.

Computer games

In 2000 Gathering of Developers released a trilogy of computer games based on the film, which greatly expanded on the myths first suggested in the film. The graphics engine and characters were all derived from the producer's earlier game, Nocturne.[33] Each game, developed by a different team, focused on different aspects of the Blair Witch mythology: Rustin Parr, Coffin Rock and Elly Kedward, respectively.

The trilogy received mixed reviews from critics, with most criticism being directed towards the very linear gameplay, clumsy controls and camera angles, and short length. The first volume, Rustin Parr, received the most praise, ranging from moderate to positive, with critics commending its storyline, graphics and atmosphere; some reviewers even claimed the game was scarier than the movie.[34] The following volumes were less well-received, with PC Gamer saying Volume 2's only saving grace was its cheap price[35] and calling Volume 3 "amazingly mediocre".[36]

Home media

The Blair Witch Project was released on DVD on October 26, 1999. Unlike the theaters, this DVD is presented in standard format.[37] The DVD included a number of special features, including "The Curse of the Blair Witch" and "The Blair Witch Legacy" featurettes, newly discovered footage, director and producer commentary, production notes, cast & crew bios and trailers.

A Blu-ray release from Lionsgate was released on October 5, 2010, The movie is the first Blu-ray Disc release to present a film in standard format.[38] Best Buy and Lionsgate had an exclusive release of the Blu-ray available on August 29, 2010.[39]

Scottish remake

In late 2009, director Stacy Hopkins was scheduled to start the shooting of the Scottish remake, The Blair Witch.[40] Since that time, no additional information has been released.

See also

- Found footage (genre)

- The Bogus Witch Project, a direct-to-video parody.

References

- ^ "Editorial: Paranormal Activity Shadows The Blair Witch". DreadCentral. http://www.dreadcentral.com/news/34337/editorial-paranormal-activity-shadows-the-blair-witch.

- ^ "The legend of the Witch lives on". BBC News. 2009-08-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/8187275.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ a b c d Klein, Joshua (1999-07-22). "Interview - The Blair Witch Project". avclub.com. http://www.avclub.com/content/node/22980. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ a b c d "Heather Donohue – Blair Witch Project". KAOS 2000 Magazine. 1999-01-01. http://www.kaos2000.net/interviews/heatherdonohue/heatherdonohue.html. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ a b Aloi, Peg (1999-07-11). "Blair Witch Project – an Interview with the Directors". Witchvox.com. http://www.witchvox.com/va/dt_va.html?a=usma&c=media&id=2416. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ a b Mannes, Brett (1999-07-13). "Something wicked". Salon.com. http://www.salon.com/ent/movies/int/1999/07/13/witch_actor/. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ Blake, Scott (2000-07-17). "An Interview With The Burkittsville 7's Ben Rock". IGN.com. http://filmforce.ign.com/articles/036/036443p1.html/. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ a b Conroy, Tom (1999-07-14). "The Do-It-Yourself Witch Hunt". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2007-10-01. http://web.archive.org/web/20071001001407/http://www.rollingstone.com/news/story/5924486/the_doityourself_witch_hunt. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (1999-08-16). "Blair Witch Craft". Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/archive/preview/0,10987,991741,00.html. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ Kaufman, Anthony (1999-07-14). "Season of the Witch". Village Voice. http://www.villagevoice.com/news/9928,kaufman,7024,1.html. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ^ Lim, Dennis (1999-07-14). "Heather Donahue Casts A Spell". The Village Voice. http://www.villagevoice.com/news/9928,lim,7025,1.html. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ^ Stanley, T.L. (1999-09-27). "High-Tech Throwback – marketing of "Blair Witch Project" – Statistical Data Included – Interview". Brandweek. http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BDW/is_36_40/ai_56023086. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ "Heather Donohue – Blair Witch Project". KAOS 2000 Magazine. 1999-01-01. http://www.kaos2000.net/interviews/heatherdonohue/heatherdonohue.html. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ John Young. "'The Blair Witch Project' 10 years later: Catching up with the directors of the horror sensation". Entertainment Weekly. http://popwatch.ew.com/2009/07/09/blair-witch.

- ^ a b John Young (July 9, 2009). "'The Blair Witch Project' 10 years later: Catching up with the directors of the horror sensation". Entertainment Weekly. http://popwatch.ew.com/2009/07/09/blair-witch/. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ^ DiOrio, Carl (2009-07-19). "Steve Rothenberg dies at 50". The Hollywood Reporter. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/content_display/film/news/e3i7c23ccda60974aa20677ac607d102241. Retrieved 2009-08-02.[dead link]

- ^ McNary, Dave (2009-07-20). "Lionsgate's Steven Rothenberg dies". Variety Magazine. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1118006188.html?categoryId=25&cs=1. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". Box Office Mojo.com. 2006-01-01. http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=blairwitchproject.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". Box Office Mojo.com. 2006-01-01. http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=blairwitchproject.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". Rotten Tomatoes.com. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/blair_witch_project/. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (1999-07-16). "The Blair Witch Project". Roger Ebert.com. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19990716/REVIEWS/907160301/1023. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

- ^ Null, Christopher (2006-01-01). "The Top 50 Movie Endings of All Time". filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 2006-08-20. http://web.archive.org/web/20060820031838/http://filmcritic.com/misc/emporium.nsf/0/394a496e465c4f38882571b900114dc5?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ Ressner, Jeffrey (1999-08-12). "Out Of Nowhere And Into Blair". Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/archive/preview/0,10987,991490,00.html. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ Chaw, Walter (2003-08-13). "Witchy Woman". Film Freak Central. http://www.filmfreakcentral.net/notes/hdonahueinterview.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ Chmielewski, Dawn C. (2006-07-13). "When fans hissed, he listened". Chicago Tribune. http://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/movies/chi-0607130142jul13,1,2398429.story?track=rss&ctrack=1&cset=true. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ B., Scott (2001-08-21). "Blair Witch Project 3 to Happen?". IGN.com. http://filmforce.ign.com/articles/304/304427p1.html. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ^ "Blair Witch 3". Yahoo Movies. 2006-01-01. Archived from the original on 2006-05-09. http://web.archive.org/web/20060509080506/http://movies.yahoo.com/shop?d=hp&cf=prev&id=1808403198. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

- ^ www.globalfilmcritics.com

- ^ The New Classics: Movies | EW 1000: Movies | Movies | The EW 1000 | Entertainment Weekly

- ^ Filmspotting, Scariest Movies, Film, Podcast, Reviews, DVDs, Adam Kempenaar

- ^ Knipfel, Jim (2005-07-22). "Cannibal Holocaust". nypress.com. http://www.nypress.com/18/45/film/Jim%20Knipfel.cfm. Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- ^ Merill, Cade (2000). "Cade Merill's The Blair Witch Files". Random House. http://www.randomhouse.com/features/blairwitch/home.html. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Smith, Jeff. 'Blair Witch Project Interview' IGN.com. April 14, 2000.

- ^ 'Metacritic: Blair Witch Volume 1: Rustin Parr'. Metacritic.

- ^ 'Metacritic – Blair Witch Volume 2' Metacritic.

- ^ 'Metacritic – Blair Witch Volume 3' Metacritic.

- ^ IGN staff. 'DVD Review of "The Blair Witch Project"' IGN.com. December 16, 1999.

- ^ http://www.blu-ray.com/movies/The-Blair-Witch-Project-Blu-ray/13876

- ^ [1] page13

- ^ "A Faux Remake of 'The Blair Witch Project'?". BloodyDisgusting. http://www.bloody-disgusting.com/news/18168.

External links

- Blair Witch, an external wiki

- Official website

- Woods Movie - The Making of The Blair Witch Project

- The Blair Witch Project at the Internet Movie Database

- The Blair Witch Project at AllRovi

- The Blair Witch Project at Box Office Mojo

- The Blair Witch Project at Rotten Tomatoes

Characters Video games Cast/crew Daniel Myrick • Eduardo SanchezRelated articles Categories:- 1999 films

- English-language films

- 1990s horror films

- American independent films

- Independent films

- American horror films

- Supernatural horror films

- Found footage films

- Camcorder films

- Witches in film and television

- Films set in 1994

- Films set in Maryland

- Films shot in Maryland

- Films shot from the first-person perspective

- Artisan Entertainment films

- Lions Gate Entertainment films

- Mockumentary films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.