- Occupation of Alcatraz

-

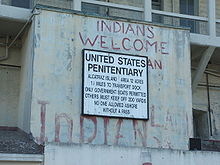

The Occupation of Alcatraz was an occupation of Alcatraz Island by the group Indians of All Tribes (IAT). The Alcatraz Occupation lasted for nineteen months, from November 20, 1969, to June 11, 1971, and was forcibly ended by the U.S. government.

Contents

Background

According to the IAT, the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) between the U.S. and the Sioux returned all retired, abandoned or out-of-use federal land to the Native people from whom it was acquired. Since Alcatraz penitentiary had been closed on March 21, 1963, and the island had been declared surplus federal property in 1964, a number of Red Power activists felt the island qualified for a reclamation.

On March 8, 1964, a small group of Sioux demonstrated by occupying the island for four hours.[1] The entire party consisted of about 40 people, including photographers, reporters, and the lawyer (Elliot Leighton) representing those claiming land stakes. According to Adam Fortunate Eagle, this demonstration was an extension of already prevalent Bay Area street theater used to raise awareness. The Sioux activists were led by Richard McKenzie, Mark Martinez, Garfield Spotted Elk, Walter Means, and Allen Cottier. Cottier acted as spokesman for the demonstration, stating that it was “peaceful and in accordance with Sioux treaty rights.” The protesters were publicly offering the federal government the same amount for the land that the government had initially offered them; at 47 cents per acre, this amounted to $9.40 for the entire rocky island, or $6.54 for the twelve usable acres. Cottier also stated that the federal government would be allowed to maintain use of the Coast Guard lighthouse located on the island.[2]

In 1969, Mohawk Richard Oakes and a larger group of activists planned another occupation on November 9. After Adam Fortunate Eagle convinced the owner of the Monte Cristo, a three-masted yacht, to pass by the island, Oakes, Jim Vaughn (Cherokee), Joe Bill (Eskimo), Ross Harden (Ho-Chunk) and Jerry Hatch jumped overboard, swam to shore, and claimed the island by right of discovery.[3] The Coast Guard quickly removed the men, but later that day, a larger group made their way to the island again, and fourteen stayed overnight. The following day, Oakes delivered a proclamation, written by Fortunate Eagle, to the General Services Administration (GSA) which claimed the island by right of discovery, after which the group left the island.

Though recently many people have claimed that the American Indian Movement was somehow involved in the Takeover, AIM had nothing to do with the planning and execution of the Occupation, though they did send a delegation to Alcatraz in the early months in order to find out how the operation was accomplished and how things were progressing.

Occupation

In the early morning hours of November 20, 1969, 79 American Indians, including students, married couples and six children, set out to occupy Alcatraz Island. A partially-successful Coast Guard blockade prevented most of them from landing, but fourteen protesters landed on the island to begin their occupation.[4]

The protesters, predominately students, drew inspiration and tactics from contemporary civil rights demonstrations, some of which they had themselves organized. The original fourteen students who occupied the Island were LaNada Means War Jack, Richard Oakes, Joe Bill, David Leach, John Whitefox, Ross Harden, Jim Vaughn, Linda Arayando, Vernell Blindman, Kay Many Horse, John Virgil, John Martell, Fred Shelton, and Rick Evening. Jerry Hatch and Al Miller, both present at the initial landing but unable to leave the boat in the confusion after the Coast Guard showed up, quickly turned up in a private boat. The first landing party was joined later by many others in the following days, including Joe Morris (a key player later as a representative of the Longshoreman's Union, which threatened to close both ports if the Occupiers were removed), and the man who would soon become 'the Voice of Alcatraz,' John Trudell.

After a fire destroyed a San Francisco Indian center and Interior Secretary Walter J. Hickel offered to turn Alcatraz into a national park, the protesters mobilized.[5][6]

The stated intention of the Occupation was to gain Indian control over the island for the purpose of building a center for Native American Studies, an American Indian spiritual center, an ecology center, and an American Indian Museum. The occupiers specifically cited their treatment under the Indian termination policy and they accused the U.S. government of breaking numerous Indian treaties.

Richard Oakes sent a message to the San Francisco Department of the Interior:

“ We invite the United States to acknowledge the justice of our claim. The choice now lies with the leaders of the American government - to use violence upon us as before to remove us from our Great Spirit's land, or to institute a real change in its dealing with the American Indian. We do not fear your threat to charge us with crimes on our land. We and all other oppressed peoples would welcome spectacle of proof before the world of your title by genocide. Nevertheless, we seek peace.[4] ” President Richard Nixon's Special Counsel Leonard Garment took over negotiations from the GSA.[4]

On Thanksgiving Day, hundreds of supporters made their way to Alcatraz to celebrate the Occupation.[4] In December, one of the occupiers, Isani Sioux John Trudell, began making daily radio broadcasts from the island, and in January 1970, occupiers began publishing a newsletter. Joseph Morris, a Blackfoot member of the local longshoreman's union, rented space on Pier 40 to facilitate the transportation of supplies and people to the island.[4]

Cleo Waterman (Seneca Nation) was president of the American Indian Center during the takeover. As an elder, she chose to stay behind and work on logistics to support the occupiers. She worked closely with Grace Thorpe and the singer Kay Starr to bring attention to the occupation and its purpose.

Grace Thorpe, daughter of Jim Thorpe (Sac and Fox), was one of the occupiers and helped convince celebrities like Jane Fonda, Anthony Quinn, Marlon Brando, Jonathan Winters, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Dick Gregory, to visit the island and show their support.[4][7] Rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival supported the Occupation with a $15,000 donation that was used to buy a boat, named the Clearwater,[6] for reliable transport to Alcatraz.[4] As a child, the actor Benjamin Bratt was in the occupation with his mother and his siblings.[8]

Collapse and removal

On January 3, 1970, Yvonne Oakes, 13-year old daughter of Annie and stepdaughter to Richard, fell to her death, prompting the Oakes family to leave the island, saying they just didn't have the heart for it anymore.[4] Some of the original occupiers left to return to school, and some of the new occupiers had drug addictions. Some non-aboriginal members of San Francisco's drug and hippie scene also moved to the island, until non-Indians were prohibited from staying overnight.[4]

By late May, the government had cut off all electrical power and all telephone service to the island. In June, a fire of disputed origin destroyed numerous buildings on the island.[4] Left without power, fresh water, and in the face of diminishing public support and sympathy, the number of occupiers began to dwindle. On June 11, 1971, a large force of government officers removed the remaining 15 people from the island.[4]

Though fraught with controversy and forcibly ended, the Occupation is hailed by many as a success for having attained international attention for the situation of native peoples in the United States, [9] and for sparking more than 200 instances of civil disobedience among Native Americans.[10]

Impact

The Occupation of Alcatraz had a direct effect on federal Indian policy and, with its visible results, established a precedent for Indian activism.

Robert Robertson, director of the National Council on Indian Opportunity (NCIO), was sent to negotiate with the protesters. His offer to build a park on the island for Indian use was rejected, as the IAT were determined to possess the entire island, and hoped to build a cultural center there. While the Nixon administration did not accede to the demands of the protesters, it was aware of the delicate nature of the situation, and so could not forcibly remove them. Spurred in part by Spiro Agnew’s support for Native American rights, federal policy began to progress away from termination and toward Indian autonomy. In Nixon’s July 8, 1970, Indian message, he decried termination, proclaiming, “self-determination among Indian people can and must be encouraged without the threat of eventual termination.” While this was a step toward substantial reform, the administration was hindered by its bureaucratic mentality, unable to change its methodical approach of dealing with Indian rights. Nixon’s attitude toward Indian affairs soured with the November 2, 1972, occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Nixon reputedly felt betrayed, and claimed that “he was through doing things to help Indians.”

Much of the Indian rights activism of the period can be traced to the Occupation of Alcatraz. The Trail of Broken Treaties, the BIA occupation, the Wounded Knee incident, and the Longest Walk all have their roots in the occupation. The American Indian Movement noted from their visit to the occupation that the demonstration garnered national attention, while those involved faced no punitive action. When AIM members seized the Mayflower II on Thanksgiving, 1970, the Occupation of Alcatraz was noted as “the symbol of a newly awakened desire among Indians for unity and authority in a white world.”[5][6]

Legacies

Some 50 of the Alcatraz occupiers traveled to the East Bay and began an occupation of a Nike Missile installation located in the hills behind the community of Kensington in June 1971. This occupation was ended after three days by a combined force of Richmond Police and regular US Army troops from the Presidio of San Francisco.[11] Moreover, the Alcatraz Occupation greatly influenced the American government's decision to end its policy of Termination and Relocation and to pass the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975.[4]

The Alcatraz Occupation led to an annual celebration of the rights of indigenous people, Unthanksgiving day, welcoming all visitors to a dawn ceremony under permits by the National Park Service.

References

- ^ Warrior, Robert and Smith, Paul Chaat. Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee. New Press, 1996. p. 10

- ^ Fortunate Eagle, Adam. Alcatraz! Alcatraz! The Indian Occupation of 1969-1971. Heyday Books, 1992.

- ^ Landings 1964 and 1969, Alcatraz is not an island, PBS

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Occupation 1969, Alcatraz is not an island, PBS

- ^ a b Johnson, Troy R. “Roots of Contemporary Native American Activism,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 20(2):127-154.

- ^ a b c Kotlowski, Dean J. “Alcatraz, Wounded Knee, and Beyond: The Nixon and Ford Administrations Respond to Native American Protest,” Pacific Historical Review, 72(2):201-227.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2003), A people's history of the United States: 1492-present, New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., p. 528, ISBN 0-06-052842-7, http://books.google.com/books?id=P8V7J5qm5-YC

- ^ Benjamin Bratt -Native Networks

- ^ Blue Cloud, Peter (1972). Alcatraz Is Not An Island. Berkeley: Wingbow Press.

- ^ Johnson, Troy R. (1996). The Occupation of Alcatraz Island. Urbana & Chicago: Illini-University of Illinois Press.

- ^ Berkeley Gazette, June 15-18, 1971

Further reading

- 1969: The Year Everything Changed, Rob Kirkpatrick. Skyhorse Publishing, 2009. ISBN 9781602393660.

- Alcatraz Is Not an Island, "Indians of All Tribes" (Peter Blue Cloud). Berkeley: Wingbow Press, 1972

- Taking Back the Rock, Native Peoples Magazine

- Johnson, Troy R. The occupation of Alcatraz Island: Indian self-determination and the rise of Indian activism. University of Illinois Press, 1996, 273 pp. ISBN 0252065859

External links

Categories:- Native American history

- Alcatraz Island

- 1969 in the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.