- Lachine massacre

-

Lachine massacre Part of King William's War, Iroquois Wars

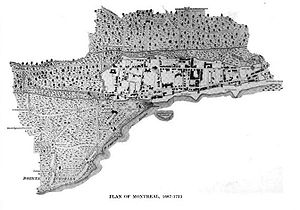

Map of Montreal, 1687 to 1723. The Lachine settlement was located southwest of Montreal proper.Date August 5, 1689 Location Lachine, New France; present-day Montreal, Quebec Result Mohawk victory Belligerents English-allied Mohawk Nation New France Strength 1,500 warriors 375, mostly civilians Casualties and losses 3 Mohawk killed 72 French settlers killed Hudson Bay (1686) – 1st Fort Albany – 1st Pemaquid – Lachine – Schenectady – Salmon Falls – Port Royal – Fort Loyal – Chedabucto – Quebec – La Prairie – York – Mohawk Valley – Wells – 2nd Fort Albany – Oyster River – York Factory – Bay of Fundy – 2nd Pemaquid – Chignecto – Fort Nashwaak – Newfoundland – Hudson Bay (1697)The Lachine massacre occurred when 1,500 Mohawk warriors attacked by surprise the small, 375 inhabitant, settlement of Lachine, New France at the upper end of Montreal Island on the morning of August 5, 1689. The attack was precipitated by growing Iroquois dissatisfaction with the increased French incursions into their territory, and was encouraged by the settlers of New England as a way to leverage power against New France. As a result of the attack, a substantial portion of the Lachine settlement was destroyed by fire and many of its inhabitants were captured or killed.

Contents

Diplomatic breakdown precedes attack

Following two decades of uneasy peace, Britain and France declared war against one another in 1689. Despite the 1669 Treaty of Whitehall, in which European forces agreed that Continental conflicts would not disrupt colonial peace and neutrality,[1] the war was fought primarily by proxy in New France and New England, and the British of New York prompted local Iroquois warriors to attack New France's undefended settlements.[2][3][4] While the British were preparing to engage in acts of warfare, the inhabitants of New France were ill prepared to defend against the Indian attacks because news of the formal declaration of conflict had not yet spread to New France.[5]

Since the establishment of New France 80 years prior, the Iroquois had seen the colonists as a threat to their sovereignty and were eager to forge an alliance with the English to subdue the French threat. In an effort to disrupt colonial forces, the Iroquois made aggressive manoeuvres against French-allied tribes such as the Huron and Illinois, who were aiding France's fur trade, a significant economic commodity for the Europeans. In response, the French, first under the Alexandre de Prouville in the 1660s, then under Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville, Marquis de Denonville in the 1680s, conducted punitive actions against the Iroquois to re-establish their dominance over the fur trade. Denonville, the Governor of New France, led 2,000 men deep into Seneca territory and destroyed their largest village.[6] The Iroquois, angered by Denonville's incursion on their land and enraged by France's effort to use their people as galley slaves, needed little incentive to strike back at the French.[6]

The Iroquois attack

On the rainy morning of August 5, 1689, Iroquois warriors used the element of surprise to launch their nighttime raid against the undefended settlement of Lachine. They traveled up the Saint Lawrence River by boat, crossed Lake Saint-Louis, and landed on the south shore of Montreal Island. While the colonists slept, the invaders surrounded their homes and waited for their leader to signal when the attack should commence.[7] They then proceeded to attack the homes, breaking down doors and windows, and dragged the colonists outside to meet their demise.[7] When some of the colonists barricaded themselves within the village's structures, the attackers set fire to the buildings and waited for them to flee the flames.[7][5] Fifty-six of the settlement's seventy-seven structures were effectively destroyed by fire.[2] Because the settlement was relatively sparse, any hope of counterattack was thwarted due to a lack of communication and an inability to organize.

Twenty-four colonists were killed in the initial raid,[8] and more than 70 were taken prisoner. The remaining colonists were able to escape the attack.[2] Of those taken prisoner, close to 50 were tortured to death (burned alive and cannibalized), while some managed to escape and 42 others were released in prisoner exchanges. A few young children were spared and actually adopted into Iroquois society.[5]

French inaction in the aftermath

Fort Rémy, also known as Fort Lachine.[9]

Fort Rémy, also known as Fort Lachine.[9]

Word of the attack spread when one of the Lachine survivors reached a local garrison, three miles (4.8 km) away, and notified the soldiers of the events that had transpired.[10] In response to the attack, two hundred soldiers, under the command of Daniel d'Auger de Subercase, along with 100 armed civilians and some soldiers from nearby Forts Rémy, Rolland and La Présentation, marched against the Iroquois.[10] They were able to defend some of the fleeing colonists from their Mohawk pursuers, but just prior to reaching Lachine they were apprehensively recalled back within the walls of Fort Rolland by order of Governor Denonville, who was attempting to pacify the local Iroquois inhabitants.[11] Governor Denonville had 700 soldiers at his disposal within the Montreal barracks, and could have easily overrun the Iroquois forces, but diplomacy was his decided course of action and he did not utilize his troops to repel the Iroquois attackers.[5]

In the days following the attack, a small group of soldiers left Fort Rémy to reach Fort Rolland, but they were intercepted by the Iroquois and the entire dispatch was killed.[11] The Iroquois roamed Montreal Island, without European intervention, for three days before boating back up the Saint Lawrence River. French inaction cost other Montreal settlements dearly as well. One month following the raid at Lachine, the Iroquois also attacked the village of La Chesnaye, killing 42 more colonists.[8]

Historical accounts

European accounts of the Lachine massacre come from two primary sources, survivors of the attack, and Catholic missionaries in the area:

Initial reports inflated the Lachine death toll significantly, and the final number of deceased, 24, was determined by examining Catholic parish registers following the attack.[8] Catholic accounts of the attack itself also exist. François Vachon de Belmont, the fifth superior of the Sulpicians of Montreal, wrote in his History of Canada:

After this total victory, the unhappy band of prisoners was subjected to all the rage which the cruellest vengeance could inspire in these savages. They were taken to the far side of Lake St. Louis by the victorious army, which shouted ninety times while crossing to indicate the number of prisoners or scalps they had taken, saying, we have been tricked, Ononthio, we will trick you as well. Once they had landed, they lit fires, planted stakes in the ground, burned five Frenchmen, roasted six children, and grilled some others on the coals and ate them.[2]Surviving prisoners of the Lachine massacre reported that 48 of their colleagues were tortured, burned and eaten shortly after being taken captive.[5] Further, the survivors themselves possessed clear signs and tales of torture.[5] Following the attack, the French colonists retrieved many English-made weapons that the Indians had left behind following their retreat from the island; this incited long-standing hatred of the English colonists of New York into demands for revenge.[5] Unfortunately, Iroquois accounts of the attack are non-existent, but French sources reported that only three of the attackers lost their lives.[7] Because all accounts of the attack are one-sided, reports of cannibalism and parents being forced to throw their children onto burning fires may be greatly exaggerated or apocryphal.[7]

Effect on Franco-English affairs

Following the events at Lachine, Denonville was recalled to France for matters unrelated to the massacre,[12][13] and Louis de Buade de Frontenac took over governorship of Montreal in October 1689.[14] Frontenac launched raids of vengeance against the English colonists to the south "in Canadien style" by attacking during the winter months of 1690.[5][15][16][17]

The Lachine massacre marked the start of three years of continuous warfare between the Iroquois and the French,[18] and Frontenac led a party of 1,000 soldiers into Iroquois land in 1696 to avenge the attack on Lachine. They disembarked from Lachine, and despite traveling far into the Mohawk territory, found no resistance and returned to Montreal. Frontenac died shortly thereafter, and was replaced as Governor of Montreal by Philippe de Rigaud Vaudreuil, who had acted on Denonville's behalf to recall Subercase following the attack on Lachine, and had assisted on Frontenac's unsuccessful excursion seven years later.[19][20]

See also

- List of massacres in Canada

- History of Montreal

- Indian massacre

Citations

- ^ "The Colonial Struggle for Acadia, The Initial Phase: 1686–1713". Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Government of Canada. April 23, 2004. Archived from the original on May 6, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20060506015750/http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/trts/hti/Marit/colo_e.html. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ a b c d "The Lachine massacre". Claiming the Wilderness: New France's Expansion. CBC. http://history.cbc.ca/history/?MIval=EpContent.html&series_id=1&episode_id=3&chapter_id=1&page_id=4&lang=E. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Winsor, p. 359 (footnote)

- ^ "The Shock Of The Attack On Lachine". Canadian Military Heritage. Government of Canada. June 20, 2004. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071011181709/http://cmhg.gc.ca/cmh/en/page_84.asp. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Denis, Ledoux. "The Lachine Massacre, 1889". When North America was Called New France. Turning Memories. http://www.turningmemories.com/lachine.html. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ a b "The Colonial Struggle for Acadia, The Initial Phase: 1686–1713". Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Government of Canada. April 23, 2004. http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/pr/trts/hti/Marit/colo_e.html. Retrieved 2007-12-01.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Borthwick, p. 10

- ^ a b c Colby, p. 111

- ^ "Militarizing New France". Canadian Military Heritage. Government of Canada. June 20, 2004. http://www.cmhg.gc.ca/cmh/en/image_73.asp?page_id=65. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ^ a b Winsor, p. 351

- ^ a b George, pp. 93–94

- ^ Campbell, p. 55

- ^ Colby, p. 115

- ^ Colby, p. 112

- ^ Campbell, p. 117

- ^ "1690: A Key Year". Canadian Military Heritage. Government of Canada. June 20, 2004. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071114235905/http://cmhg.gc.ca/cmh/en/page_85.asp. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ^ Colby, p. 116

- ^ Colby, p. 141-152

- ^ Borthwick, p. 11

- ^ Borthwick, p. 105

References

- Borthwick, John Douglas (1892). History and Biographical Gazetteer of Montreal to the Year 1892. Montreal: John Lovell (no copyright in the United States). http://books.google.com/books?id=VdP7-6le46oC.

- Campbell, Thomas Joseph (1916). Pioneer Laymen of North America. Boston: The America Press (No copyright in the United States). http://books.google.com/books?id=EerTTAyYxkwC.

- Colby, Charles William (1915). The Fighting Governor: A Chronicle of Frontenac. New York: Glasgow, Brook & Company (No copyright in the United States). http://books.google.com/books?id=Gu0NAAAAIAAJ.

- George, Charles; Douglas Roberts (1897). A History of Canada. Boston: The Page Company (no copyright in the United States). http://books.google.com/books?id=YU2uIK42giYC.

- Winsor, Justin (1884). Narrative and Critical History of America. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company (no copyright in the United States). http://books.google.com/books?id=F5MLAAAAIAAJ&dq.

Categories:- History of Canada

- Conflicts in 1689

- Battles involving the Iroquois

- Massacres in Canada

- Massacres by Native Americans

- Indian massacres

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.