- Origins of the Hyksos

-

The Hyksos rulers of the fifteenth dynasty of Egypt were of non-Egyptian origin. There are various hypotheses as to their ethnic identity. Most archaeologists describe the Hyksos as Semitic peoples from Asia since the names of their rulers such as Khyan and Sakir-Har incorporated Semitic names. The Hyksos kingdom was centered in the eastern Nile Delta and Middle Egypt and was limited in size, never extending south into Upper Egypt, which was under control by Theban-based rulers except for Thebes's port city of Elim at modern Quasir. Hyksos relations with the south seem to have been mainly of a commercial nature, although Theban princes appear to have recognized the Hyksos rulers and may possibly have provided them with tribute for a period. The Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty rulers established their capital and seat of government at Memphis and their summer residence at Avaris.

Contents

Hyksos 15th dynasty

Hyksos

in hieroglyphsThe rule of these Hyksos kings overlaps with those of the native Egyptian pharaohs of the 16th and 17th dynasties of Egypt, better known as the Second Intermediate Period. The first pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, Ahmose I, finally expelled the Hyksos from their last holdout at Sharuhen in Gaza by the 16th year of his reign.[1][2] Scholars have taken the increasing use of scarabs and the adoption of some Egyptian forms of art by the Fifteenth Dynasty Hyksos kings and their wide distribution as an indication of their becoming progressively Egyptianized.[3] The Hyksos used Egyptian titles associated with traditional Egyptian kingship, and took Egyptian god Seth to represent their own titulary deity.[4]

It would appear as though Hyksos administration was accepted in most quarters, if not actually supported by many of their northern Egyptian subjects. The flip side is that in spite of the prosperity that the stable political situation brought to the land, the native Egyptians continued to view the Hyksos as non-Egyptian "invaders." When they eventually were driven out of Egypt, all traces of their occupation were erased. There is no surviving accounts that record the history of the period from the Hyksos perspective, only that of the native Egyptians who evicted the occupiers, in this case the rulers of Eighteenth Dynasty who were the direct successor of the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty. It was the latter which started and led a sustained war against the Hyksos. Some think that the native kings from Thebes had an incentive to demonize the Asiatic rulers in the North, thus accounting for the destruction of their monuments. From this viewpoint the Hyksos dynasties represent superficially Egyptianized foreigners who were tolerated, but not truly accepted, by their Egyptian subjects. In contrast scholars such as John A. Wilson found that the description of the Hyksos as overpowering, irreligious foreign rulers had support from other sources.[5]

The origin of the term "Hyksos" derives from the Egyptian expression heka khasewet ("rulers of foreign lands"), used in Egyptian texts such as the Turin King List to describe the rulers of neighbouring lands. This expression begins to appear as early as the late Old Kingdom[citation needed] in Egypt, referring to various Nubian chieftains, and as early as the Middle Kingdom, referring to the Semitic chieftains of Syria and Canaan.

The names, the order, and even the total number of the Fifteenth Dynasty rulers are not known with full certainty. The names appear in hieroglyphs on monuments and small objects such as jar lids and scarabs. In those instances in which Prenomen and Nomen do not occur together on the same object, there is no certainty that the names belong together as the two names of a single person. The Danish Egyptologist Kim Ryholt sums up the complex situation by stating that "there are only vague indications of the origin of the Fifteenth Dynasty" and concurring that the small number of surviving names of the Fifteenth Dynasty are "too few to allow for general conclusions" about the Hyksos' background in his 1997 study of the Second Intermediate Period.[6] Furthermore, Ryholt stresses that:

- "we also lack positive indications that any of the rulers of the Fifteenth Dynasty were related by blood, and, accordingly we could be dealing with a dynasty of mixed ethnic origin."[7]

Manetho's history of Egypt is known only through the works of others, such as Against Apion by Flavius Josephus. These sources do not list the names of the six rulers in the same order. To complicate matters further, the spellings are so distorted that they are useless for chronological purposes; there is no close or obvious connection between the bulk of these names — Salitis, Beon or Bnon, Apachnan or Pachnan, Annas or Staan, Apophis, Assis or Archles — and the Egyptian names that appear on scarabs and other objects. The Turin king list affirms there were six Hyksos rulers, but only four of them are clearly attested as Hyksos kings from the surviving archaeological or textual records: 1. Sakir-Har, 2. Khyan, 3. Apophis and 4. Khamudi.

Khyan and Apophis are by far the best attested kings of this dynasty whereas Sakir-Har is attested by only a single door jamb from Avaris which bears his royal titulary. Khamudi is named as the last Hyksos king on a fragment from the Turin Canon. The hieroglyphic names of these Fifteenth Dynasty rulers exist on monuments, scarabs, and other objects

Two Hyksos pharaohs remain unknown. Many scholars have suggested they were Maaibre Sheshi, Aper-Anath, Samuqenu, Sekhaenre Yakbim or Meruserre Yaqub-Har (who are all attested by seals or scarabs in the Delta region) but thus far, all that is certain is that they were Asiatic kings in the Egypt's Delta region. They could be either the remaining two Hyksos kings or were members of the previous Fourteenth Dynasty at Xois.

Origin hypotheses

Manetho and Josephus

In his Against Apion, the 1st-century AD historian Josephus Flavius debates the synchronism between the Biblical account of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, and two Exodus-like events that the Egyptian historian Manetho apparently mentions. It is difficult to distinguish between what Manetho himself recounted, and how Josephus or Apion interpret him.

Josephus identifies the Israelite Exodus with the first exodus mentioned by Manetho, when some 480,000 Hyksos "shepherd kings" (also referred to as just as 'shepherds', as 'kings' and as 'captive shepherds' in his discussion of Manetho) left Egypt for Jerusalem.[8] The mention of "Hyksos" identifies this first exodus with the Hyksos period (16th century BC).

Apion identifies a second exodus mentioned by Manetho when a renegade Egyptian priest called Osarseph led 80,000 "lepers" to rebel against Egypt. Apparently Manetho conflates events of the Amarna period (in the 14th century) and the events at the end of the 19th Dynasty (12th century).[citation needed] Then Apion additionally conflates these with the Biblical Exodus, and contrary to Manetho, even alleges that this heretic priest changed his name to Moses.[9] Many scholars[10][11] interpret "lepers" and "leprous priests" non-literally: not as a disease but rather as a strange and unwelcome new belief system.

Josephus records the earliest account of the false but understandable etymology that the Greek phrase Hyksos stood for the Egyptian phrase Hekw Shasu meaning the Bedouin-like "Shepherd Kings", which scholars have only recently shown means "rulers of foreign lands".[12]

Modern scholarship

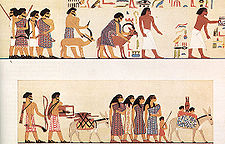

A group of people labelled Asiatics shown entering Egypt c.1900 BC from the tomb of a 12th dynasty official Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan. The glyphs above are above the head of the first animal

A group of people labelled Asiatics shown entering Egypt c.1900 BC from the tomb of a 12th dynasty official Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan. The glyphs above are above the head of the first animal

As to a Hyksos “conquest,” some archaeologists depict the Hyksos as “northern hordes . . . sweeping through Palestine and Egypt in swift chariots.” Yet, others refer to a ‘creeping conquest,’ that is, a gradual infiltration of migrating nomads or seminomads who either slowly took over control of the country piecemeal or by a swift coup d’etat put themselves at the head of the existing government. In The World of the Past (1963, p. 444), archaeologist Jacquetta Hawkes states: “It is no longer thought that the Hyksos rulers... represent the invasion of a conquering horde of Asiatics... they were wandering groups of Semites who had long come to Egypt for trade and other peaceful purposes.”

It is usually assumed that the Hyksos were likely Semites who came from the Levant. Kamose's explicit statement about the Asiatic origins of Apophis is the strongest evidence for a Canaanite background for the majority of the Hyksos. But other interpretations are possible.

Hurrians or Indo-Europeans

Contemporary with the Hyksos there was an widespread Indo-Aryan expansion in central and south Asia. The Hyksos used the same horsedrawn chariot as the Indo-Aryans and Egyptian sources mentions a rapid conquest. The German Egyptologist Wolfgang Helck once argued that the Hyksos were part of massive Hurrian and Indo-Aryan migrations into the Near East. According to Helck, the Hyksos were Hurrians and part of a Hurrian empire that, he claimed, extended over much of Western Asia at this period. However Helck himself pointed out that where is no evidence of a grand scale Hurrian invasion in a 1993 article[13] But in the same article he also noted the possibility of a sea invasion of Indo-European peoples from mainly Anatolia. However, this hypothesis is not supported by most scholars.

Amorites or West-semites

Kamose, the last king of the Theban 17th Dynasty, refers to Apophis as a "Chieftain of Retjenu (i.e. Canaan)" in a stela which implies a Canaanite background for this Hyksos king. Khyan's name "has generally been interpreted as Amorite "Hayanu" (reading h-ya-a-n) which the Egyptian form represents perfectly, and this is in all likelihood the correct interpretation."[14] Ryholt furthermore observes the name Hayanu is recorded in the Assyrian king-lists for a "remote ancestor" of Shamshi-Adad I (c.1800 BC) of Assyria, which suggests that it had been used for centuries prior to Khyan's own reign.[15]

The issue of Sakir-Har's name, one of the three earliest 15th Dynasty kings, also leans towards a West Semitic or Canaanite origin for the Hyksos rulers—if not the Hyksos peoples themselves. As Ryholt notes, the name Sakir-Har:

“ is evidently a theophorous name compounded with hr, Canaanite harru, [or] 'mountain.' This sacred or deified mountain is attested in at least two other names which are both West Semitic (Ya'qub-Har and Anar-Har) and so there is reason to suspect that the present name also may be West Semitic. The element skr seems to be identical with śkr, 'to hire, to reward', which occurs in several Amorite names. Assuming that śkr takes a nominal form as in the names sa-ki-ru-um and sa-ka-ŕu-um, the name should be transliterated as either Sakir-Har or Sakar-Har. The former two names presumably mean 'the Reward' Accordingly, the name here under consideration would mean 'Reward of Har.'[16] ” References

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.193. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. History and Chronology of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt: Seven Studies, pp.46–49. University of Toronto Press, 1967.

- ^ Booth, Charlotte. The Hyksos Period in Egypt. p.15-18. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1

- ^ Booth, Charlotte. The Hyksos Period in Egypt. p.29-31. Shire Egyptology. 2005. ISBN 0-7478-0638-1

- ^ "The culture of ancient Egypt", John Albert Wilson, p. 160, University of Chicago Press, org. pub 1956 -still in print 2009,ISBN 0226901521

- ^ Kim Ryholt, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c.1800-1550 B.C., Museum Tuscalanum Press, 1997. p.126

- ^ Ryholt, op. cit., p.126 An example given by Ryholt "is the family of the kings Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin of Larsa. Their father had been the ruler of two Amorite tribes, but both he and their grandfather had Elamite names, while they themselves had Akkadian names, and a sister of theirs had a Sumerian name.

- ^ Josephus, Flavius, Against Apion, 1:86–90.

- ^ Josephus, Flavius, Against Apion, 1:234–250.

- ^ Miriam - From Prophet to Leper

- ^ Egyptian Account of the Leper's Exodus

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel and Silberman, Neil AsherThe Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, 2001, The Free Press, New York City, ISBN 0-684-86912-8 p. 54

- ^ see W. Helck's Orientalia 62 (1993) Das Hyksosproblem pp.60–66 paper

- ^ Ryholt, Kim SB. The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c.1800-1550 B.C. (1997) by Museum Tuscalanum Press, p.128

- ^ Ryholt, Ibid., p.128

- ^ Ryholt, op. cit., pp.127–128

Categories:- Origin hypotheses of ethnic groups

- Ancient Egypt

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.