- George Padmore

-

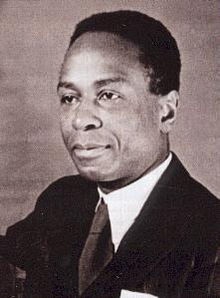

George Padmore

Born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse

June 28, 1903

Arouca, TrinidadDied September 23, 1959 (aged 56)

London, EnglandNationality Trinidadian George Padmore (1903 – 1959), born Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, was a Trinidadian communist who became a leading Pan-Africanist in his later years.

Contents

Biography

Early years

Malcolm Ivan Meredith Nurse, better known by his pseudonym George Padmore, was born June 28, 1903 in Arouca, Trinidad, then part of the British West Indies. His paternal great-grandfather was an Ashanti warrior who was taken prisoner and sold into slavery at Barbados, where his grandfather was born.[1] Nurse worked as a journalist in the West Indies; then, in 1924, travelled to Fisk University in Tennessee where he studied medicine. He later registered at New York University but soon transferred to Howard University.

Communist

During his college years Nurse became involved with the Workers (Communist) Party and changed his name to George Padmore. Padmore officially joined the Communist Party in 1927 and was active in its mass organization targeted to black Americans, the American Negro Labor Congress.[2] In March 1929 Padmore was a fraternal (non-voting) delegate to the 6th National Convention of the CPUSA, held in New York City.[3]

Padmore, an energetic worker and prolific writer, was tapped by Communist Party trade union leader William Z. Foster as a rising star and was taken to Moscow to deliver a report on the formation of the Trade Union Unity League to the Communist International later in 1929.[2] Following the delivery of his report, Padmore was asked to stay on in Moscow to head the Negro Bureau of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profintern).[2] He was even elected to the Moscow City Soviet,[2] an institution roughly equivalent to city councils in the west.

As head of the Profintern's Negro Bureau Padmore helped to produce pamphlet literature and contributed articles to Moscow's English-language newspaper, the Moscow Daily News.[4] He was also used periodically as a courier of funds from Moscow to various foreign Communist Parties.[5]

In July 1930, Padmore was instrumental in organizing an international conference in Hamburg, Germany which launched a Comintern-backed international organization of black labor organizations called the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW).[5] Padmore lived in Vienna, Austria during this time, where he edited the monthly publication of the new group, The Negro Worker.[5]

In 1931, Padmore moved to Hamburg and accelerated his writing output, continuing to produce the ITUCNW magazine and writing more than 20 pamphlets in a single year.[5] This German interlude came to an abrupt close by the middle of 1933, however, as the offices of the Negro Worker were ransacked by ultra-nationalist gangs following the Nazi seizure of power.[6] Padmore was deported to England by the German government, while the Comintern placed the ITUCNW and its Negro Worker on hiatus in August 1933.[6]

Disillusioned by what he perceived as the Comintern's flagging support for the cause of the liberation of colonial peoples in favor of the Soviet Union's pursuit of diplomatic alliances with the colonial powers themselves, Padmore abruptly severed his connection with the ITUCNW late in the summer of 1933.[6] He was called upon by the Comintern's disciplinary body, the International Control Commission (ICC), to explain his unauthorized action. When he refused to do so, the ICC expelled him from the Communist movement on February 23, 1934.[6] A phase of Padmore's political journey was at an end.

Pan-Africanist

Over time, Padmore's ardent belief in communism dissipated and he began to shift his focus to Africa.[7]

One consequence of Padmore's travel to the Soviet Union was an end of his time as a resident of the United States. As a non-citizen[3] and a communist, Padmore was effectively barred from reentry to America once he had departed.[7]

In 1934 Padmore resigned his positions and moved to London, where he collaborated with C.L.R. James and other Caribbean and African intellectuals. In response to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia James and Padmore organised the International African Services Bureau, of which he was chairman and James editor.[8] In his capacity as leader of the IASB Padmore helped organise the 1945 Manchester Conference which was attended by Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta, W. E. B. Du Bois, Jaja Wachuku. This conference helped set the agenda for decolonisation in the post-war period.

When Ghana became independent in 1957 Padmore moved there and served as an advisor to Nkrumah.

Death and legacy

Padmore died in London, where he had gone for medical treatment, on September 23, 1959.

Footnotes

- ^ Kevin Kelly Gaines, American Africans in Ghana: Black Expatriates and the Civil Rights Era. UNC Press Books, 2006; pg. 27.

- ^ a b c d Mark Salomon, The Cry was Freedom: Communists and African-Americans, 1917-36. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998; pg. 60.

- ^ a b Russian State Archive for Socio-Political History (RGASPI), Moscow, fond 515, opis 1, delo 1600, list 33. Available on microfilm as "Files of the Communist Party of the USA in the Comintern Archives," IDC Publishers, reel 122.

- ^ Salomon, The Cry was Freedom, pp. 177-178.

- ^ a b c d Salomon, The Cry was Freedom, pg. 178.

- ^ a b c d Salomon, The Cry was Freedom, pg. 179.

- ^ a b Salomon, The Cry was Freedom, pg. 177.

- ^ C.L.R. James, Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution. London: Allison & Busby, 1977; pp. 63 et seq.

Works

- The Life and Struggles of Negro Toilers (1931)

- How Britain Rules Africa (1936)

- Africa and World Peace (1937)

- The White Man's Duty: An analysis of the colonial question in the light of the Atlantic Charter (with Nancy Cunard) (1942)

- The Voice of Coloured Labour (Speeches and reports of Colonial delegates to the World Trade Union Conference, 1945) (editor) (1945)

- How Russia Transformed her Colonial Empire: a challenge to the imperialist powers (with Dorothy Pizer) (1946)

- "History of the Pan-African Congress (Colonial and coloured unity: a programme of action)" (editor) (1947) reprinted in The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress revisited by Hakim Adi and Marika Sherwood (1995)

- Africa: Britain's Third Empire(1949)

- The Gold Coast Revolution: the struggle of an African people from slavery to freedom (1953)

- Pan-Africanism or Communism? The Coming Struggle for Africa (1956)

Further reading

- Fitzroy Baptiste and Rupert Lewis, George Padmore: Pan-African Revolutionary. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 2009. —Essays by Padmore.

- Christian Høgsbjerg, "A forgotten fighter," International Socialism, whole no. 124 (2009).

- James Ralph Hooker, Black Revolutionary: George Padmore's Path from Communism to Pan-Africanism. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967.

- Holger Weiss, "The Road to Hamburg and Beyond: African American Agency and the Making of a Radical African Atlantic, 1922-1930." Part One. | Part Two. | Part Three. Comintern Working Papers, Åbo Akademi University, 2007.

- Holger Weiss, "The Hamburg Committee, Moscow and the Making of a Radical African Atlantic, 1930-1933." Part One: The RILU and the ITUCNW. | Part Two: The ISH, the IRH and the ITUCNW. | Part Three: The LAI and the ITUCNW. Comintern Working Papers, Åbo Akademi University, 2010.

External links

- George Padmore Internet Archive, Marxists Internet Archive, www.marxists.org./ —Selected writings by Padmore.

- The George Padmore Institute, London. www.georgepadmoreinstitute.org/

Categories:- 1902 births

- 1959 deaths

- Pan-Africanism

- Fisk University alumni

- Howard University alumni

- New York University alumni

- Marxist writers

- Trinidad and Tobago communists

- Trinidad and Tobago writers

- Trinidad and Tobago people of Ghanaian descent

- Members of the Communist Party USA

- Comintern people

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.