- Allegheny woodrat

-

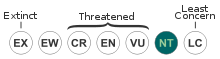

Allegheny Woodrat Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Rodentia Family: Cricetidae Genus: Neotoma Subgenus: Neotoma Species: N. magister Binomial name Neotoma magister

Baird, 1857

Allegheny Woodrat range The Allegheny woodrat, Neotoma magister, is a species of "pack rat" in the genus Neotoma. Once believed to be a subspecies of the Eastern Woodrat or Florida Woodrat, Neotoma floridana, extensive DNA analysis has proven it to be a distinct species.[2]

Contents

Description

The Allegheny woodrat is a medium-sized rodent resembling an oversized White-footed Mouse more than the Norway Rat.[citation needed] It is the second largest member of the native North American rats and can weigh up to a pound, roughly the size of an eastern gray squirrel. Typical or average size is about 325-375 grams for an adult. An adult woodrat ranges about 15 to 18 inches in length whereas 7 to 8 inches of this is tail. The fur is long, soft, and brownish-gray or cinnamon in color, while the undersides and feet are white. They have large eyes, naked ears, and long whiskers. Its most distinguishing feature is its tail: while the tails of European rats are naked with only slightly visible hairs, the woodrat's tail is completely furred with hairs about one-third of an inch long and predominantly black above and white beneath.

Habitat

The Allegheny Woodrat prefers rocky outcrops associated with mountain ridges such as cliffs, caves, talus slopes, and even mines. This is mostly true for Pennsylvania and Maryland. In Virginia and West Virginia, woodrats are found on ridges but also on side slopes in caves and talus (boulders and breakdown) fields. The surrounding forest is usually deciduous.[3]

Diet

The Allegheny Woodrat's diet primarily consists of plant materials including buds, leaves, stems, fruits, seeds, acorns and other nuts. They store their food in caches and eat about five percent of their body weight a day.[4]

Life history

Nocturnal, the Allegheny Woodrat spends its nights foraging, collecting food and nesting materials, very rarely traveling more than 150 feet from its home range. They also collect and store various non-food items such as bottle caps, snail shells, coins, gun cartridges, feathers and bones. This trait is responsible for the nickname "trade" or "pack rat".[4] These rats form small colonies in which their nesting areas consist of a network of underground runways and many conspicuous latrines. Latrines are large fecal piles the rats deposit on protected flat rocks.[3] In some cases, researchers have found dried leaves placed around the nesting area which appear to act as alarms to warn the rats of approaching danger.[5]

Unlike their cousins, the Allegheny Woodrat is not a prolific breeder, averaging only one to three young per litter (average in one Virginia study was 2) and generally have one or sometimes two litters per year ideal conditions. Their gestation period is usually 30 to 37 days and are weaned within a month's time. In the wild, the Allegheny Woodrat has been known to live up to three years.[5] Researchers in Virginia and West Virginia have documented longevity up to 54 months in the wild although 1–2 years is typical.

Predators

Predators include owls, skunks, weasels, foxes, raccoons, bobcats, large snakes, and humans. At one point, the Allegheny rat was hunted for food and sometimes killed due to false identification based on its resemblance of more problematic European rats.[5]

Distribution and status

Distribution mainly occurs along the Appalachian Mountain range. Historically found as far north as Connecticut where it is now extinct, southeastern New York (near extinct), northern New Jersey, and northern Pennsylvania southwestward through western Maryland, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, northern and western Virginia to northeastern Alabama and northwestern North Carolina with isolated populations north of the Ohio River in southern Ohio and southern Indiana. The Tennessee River is generally accepted as the southern range limit.[2]

Although the Allegheny Woodrat is not federally listed, it is in major decline and is state listed.

State Status AL Threatened CT Extirpated – extinct – special concern GA Threatened IN Endangered KY Apparently Secure MD Endangered MA Expirated – extinct NC Endangered NJ Endangered NY Endangered OH Endangered PA Threatened TN Threatened VA Threatened WV Threatened Causes and management of decline

Gypsy moth defoliation of hardwoods along the Allegheny Front near Snow Shoe, Pennsylvania, in July 2007.

Gypsy moth defoliation of hardwoods along the Allegheny Front near Snow Shoe, Pennsylvania, in July 2007.

In parts of their range (New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania), the Allegheny Woodrat population has been in decline over the past thirty years. They have been extipated from Connecticut, New York and parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maryland. The reasons for the decline is not yet entirely understood but is believed to be caused by a combination of factors. The first reason is a parasite, the raccoon roundworm, Baylisascaris procyonis, which is almost always fatal to the Woodrat.[7] The raccoon, which easily adapts to environmental change, and has thrived in the traditional woodrat habitat, increasing infection by the parasite, which enters the woodrat because it eats the plant and seed material in the raccoon's feces. Another frequently cited cause is severe defoliation of American chestnuts caused by chestnut blight and of oaks by an invasion of gypsy moths (lowering available supplies of acorns for the woodrat). Predation by Great Horned Owls has also been cited. Finally, increased human encroachment causes fragmentation and destruction of the woodrat's habitat.[8]

Indiana's Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program currently monitors status, distribution and population. They are also conducting field searches for new localities and research to identify the factors for decline.[4]

New Jersey's Division of Fish and Wildlife's Endangered and Nongame Species Program supported research by Kathleen LoGiudice. She developed a drug to be distributed through bait that the raccoons would eat, disrupting the growth and shedding of the roundworm parasite for about 3 weeks, effectively reducing the disposition of roundworm eggs near woodrat nesting sites and therefore reducing the threat of the parasite in woodrats.[9]

Pennsylvania is conducting a 3 year study partially funded by a Game and Commission State Wildlife Grant and being led by Indiana University of Pennsylvania in an attempt to shed light on the daily and seasonal movements of woodrats, identify high quality woodrat habitat, and learn whether providing food caches can boost a population. Their work will include radio-telemetry, DNA profiling and mark-recapture trapping.[10][11]

Maryland's Dept. of Natural Resources conducts trappings and surveys to study the Woodrat's habitat.[12]

References

- ^ Linzey, A.V. & NatureServe (Hammerson, G., Whittaker, J.C. & Norris, S.J.) (2008). Neotoma magister. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 3 August 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of near threatened.

- ^ a b c "natureserv"

- ^ a b "Pennsylvania Game Commission"

- ^ a b c "Indiana Division of Fish and Wildlife"

- ^ a b c " NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation"

- ^ "Team Woodrat status"

- ^ "Allegheny Woodrat in Alabama"

- ^ Balcom, Betsie J.; Richard H. Yahner (April 1996). "Microhabitat and Landscape Characteristics Associated with the Threatened Allegheny Woodrat". Conservation Biology 10 (2): 515–25. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020515.x. JSTOR 2386866.

- ^ "Allegheny Woodrat - New Jersey"

- ^ "A Rocky Existence: The Woodrat In Pennsylvania". The Outdoor Wire. 17 July 2007. http://www.theoutdoorwire.com/tow_release.php?ID=118823&session=27qrtr69j7ahm7fe. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- ^ "A Rocky Existence"

- ^ "In Pursuit of the Allegheny Woodrat"

External links

- "Allegheny Woodrat Fact Sheet" at dec.ny.gov

- "Have You Discovered a Woodrat?" at dickinson.edu

Categories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Neotominae

- Mammals of the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.