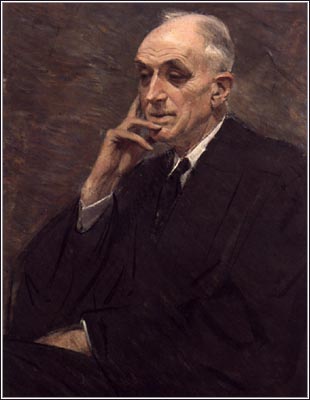

- John Marshall Harlan II

Infobox Judge

name = John Marshall Harlan

imagesize =

caption =

office = Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court

termstart = March 28, 1955

termend = September 23, 1971

nominator =Dwight D. Eisenhower

appointer =

predecessor =Robert H. Jackson

successor =William Rehnquist

office2 =

termstart2 =

termend2 =

nominator2 =

appointer2 =

predecessor2 =

successor2 =

birthdate = birth date|mf=yes|1899|5|20|mf=y

birthplace = Chicago,Illinois

deathdate = death date and age|mf=yes|1971|12|29|1899|5|20|mf=y

deathplace =Washington, D.C.

spouse =

religion =Episcopal Church in the United States of America John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. He was the grandson of his namesake,

John Marshall Harlan , another associate justice who served from 1877 to 1911.Harlan is often characterized as a member of the conservative wing of the Warren Court. He advocated a limited role for the judiciary, remarking that the Supreme Court should not be considered "a general haven for reform movements." In general, Harlan adhered more closely to precedent, and was more reluctant to overturn legislation, than many of his colleagues on the Court. He strongly disagreed with the doctrine of incorporation, which held that the guarantees of the federal Bill of Rights were applicable at the state level. At the same time, he advocated a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause, arguing that it protected a wide range of rights not expressly mentioned in the

United States Constitution . Harlan is sometimes called the "great dissenter" of the Warren Court, and is often regarded as one of the most influential Supreme Court justices in the twentieth century.Early life and career

John Marshall Harlan was born on May 20, 1899 in

Chicago ,Illinois . He was the son of John Maynard Harlan, a Chicago lawyer and politician, and Elizabeth Flagg. Histroically, Harlan's family had been politically active. His forebear, George Harlan, served as one of governors of Delaware during the seventeenth century;cite web|last=Harlan|first=Louis R.|title=Harlan Family In America: A Brief History|url=http://www.harlanfamily.org/book.htm| accessdate=9 Octorber 2008|publisher=Harlan Family in America] his great-grandfather, James Harlan, was a congressman during the 1830s; his grandfather, alsoJohn Marshall Harlan , was a Justice of the United States Supreme Court; and his uncle was chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission.Dorsen, 2002, pp.139–143]In his younger years, Harlan attended

The Latin School of Chicago .Yarbrough, 1992, pp.10–11] He later attended two boarding high schools inCanada ,Upper Canada College inToronto , andAppleby College also near Toronto. Upon graduation from Appleby, Harlan returned to the U.S. and in 1916 enrolled atPrinceton University . There, he was a member of theIvy Club , served as an editor of "The Daily Princetonian ", and was class president during his junior and senior years. After graduating from the university in 1920, he received aRhodes Scholarship , which he used to attendBalliol College, Oxford .cite book|last=Leitch|first=Alexander|year=1978|title=A Princeton Companion|location=Princeton|publisher=Princeton University Press] He studied jurisprudence at Oxford for three years, returning from England in 1923. Upon his return to the United States, he began work with the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland (now known asDewey & LeBoeuf ), one of the leading law firms in the country, while studying law atNew York Law School .Yarbrough, 1992, pp.13–16] He received his law degree in 1924 and earned admission to the bar in 1925. In 1928, he married Ethel Andrews, with whom he had one daughter, Eva Dillingham.cite web|url=http://www.michaelariens.com/ConLaw/justices/harlan2.htm|author=Ariens, Michael|title=John Marshall Harlan II|accessdate=2008-08-14]Between 1925 and 1927, Harlan served as Assistant

U.S. Attorney for theSouthern District of New York , heading the district'sProhibition unit. He prosecuted Harry M. Daugherty, formerUnited States Attorney General. In 1928, he was appointed Special Assistant Attorney General ofNew York , in which capacity he investigated a scandal involving sewer construction inQueens . He prosecutedMaurice E. Connolly , the Queensborough president , for his involvement in the affair.cite web|url=http://infoshare1.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/finding_aids/harlan/|title=John Marshall Harlan Papers|publisher=Princeton University Library|accessdate=2008-08-14] In 1930, Harlan returned to his old law firm, becoming a partner one year later. At the firm, he long served as chief assistant forEmory Buckner . After his death Harlan become a leading trial lawyer at the firm.In 1937, Harlan was one of five founders of the controversial

Pioneer Fund , a group associated witheugenics advocacy. In private practice, he handled a variety of notable cases. In 1940, for example, he represented the New York Board of Higher Education in its unsuccessful effort to retainBertrand Russell on the faculty of theCity College of New York ; Russell was declared "morally unfit" to teach.Yarbrough, 1992, pp.52–53]During

World War II , Harlan volunteered for military duty, serving as a colonel in the United States Army Air Force from 1943 to 1945. He was the chief of theOperational Analysis Section of the Eighth Air Force in England. He won theLegion of Merit from the United States, and theCroix de guerre from bothFrance andBelgium . In 1946 Harlan returned to private law practice. In 1951, however, he returned to public service, serving as Chief Counsel to the New York State Crime Commission.upreme Court career

On January 13, 1954,

United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated Harlan to theUnited States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit , to fill a vacancy created by the death of JudgeAugustus Noble Hand . He was confirmed by theUnited States Senate on February 9, and took office on February 10.cite web|url=http://www.fjc.gov/servlet/tGetInfo?jid=979| publisher=Federal Judicial Center|title=Marshall, John Harlan|accessdate=2008-08-14] Harlan knew this court well, as he had often appeared before it. However, his stay on the court only lasted for a year. On January 10, 1955, President Eisenhower nominated Harlan to the United States Supreme Court following the death of JusticeRobert H. Jackson .Harlan's nomination came shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in "

Brown v. Board of Education ", ussc|347|483|1954] declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, James Eastland, and several southern senators delayed his confrimation, because they (correctly) believed that he would support desegregation of the schools and civil rights.cite journal|last=Dorsen|first=Norman|title=The selection of U.S. Supreme Court justices|year=2006|journal=International Journal of Constitutional Law|volume=4|issue=4|pages=652–663|doi=10.1093/icon/mol028| url=http://icon.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/4/4/652] Unlike almost all previous Supreme Court nominees, Harlan appeared before theUnited States Senate Committee on the Judiciary to answer questions relating to his judicial views. This appearance set a new precedent; since Harlan, every Supreme Court nominee has been questioned by the Judiciary Committee.cite web|url=http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Nominations.htm |title=United States Senate. Nominations|accessdate=9 October 2008|publisher=United States Senate] The Senate finally confirmed him on March 17, 1955 by a vote of 71–11.cite journal|last=Epstein|first=Lee|coauhtors=Segal, Jeffrey A.;Staudt, Nancy; and Lindstädt, Rene|title=The role of qualifications in the confirmation of nominees to the U.S. Supreme court|journal=Florida State University Law Review|year=2005|volume=32|pages=1145–1174|url=http://www.law.fsu.edu/journals/lawreview/downloads/324/Epstein.pdf|format=pdf] He took seet on March 28, 1955. Of the eleven senators who voted against his appointment, nine were from the South. He was replaced on the Second Circuit byJoseph Edward Lumbard .cite news|author=Ravo, Nick|title=J. Edward Lumbard Jr., 97, Judge and Prosecutor, Is Dead|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F02E2D61239F934A35755C0A96F958260&sec=&spon=|accessdate=9 october 2008|date=June 9, 1999|publisher=The New York Times|location=New York]On the Supreme Court, Harlan often voted alongside Justice

Felix Frankfurter . He was an ideological adversary—but close personal friend—of JusticeHugo Black ,cite web|url=http://www.oyez.org/oyez/resource/legal_entity/89/|author=Goldman, Jeremy|title=Harlan, John M.|accessdate=2008-08-14] with whom he disagreed on a variety of issues, including the applicability of the Bill of Rights to the states, the Due Process Clause, and theEqual Protection Clause .Jurisprudence

Harlan's jurisprudence is often characterized as conservative. He held precedent to be of great importance, adhering to the principle of "

stare decisis " more closely than many of his Supreme Court colleagues. Unlike his contemporary Hugo Black, he eschewed stricttextualism . While he believed that the original intention of the Framers should play an important part in constitutional adjudication, he also held that broad phrases like "liberty" in the Due Process Clause could be given an evolving interpretation.Harlan believed that most problems should be solved by the political process, and that the judiciary should play only a limited role. In his dissent to "

Reynolds v. Sims ",ussc|377|533|1964, Harlan J., dissenting] he wrote:These decisions give support to a current mistaken view of the Constitution and the constitutional function of this court. This view, in short, is that every major social ill in this country can find its cure in some constitutional principle and that this court should take the lead in promoting reform when other branches of government fail to act. The Constitution is not a panacea for every blot upon the public welfare nor should this court, ordained as a judicial body, be thought of as a general haven of reform movements.

Equal Protection Clause

The Supreme Court decided several important civil rights cases during the first years of Harlan's career. In these cases, Harlan regularly sided with the

civil rights movement —similar to his grandfather, the only dissenting justice in the infamousPlessy v. Ferguson case.ussc|163|537|1896, Harlan J., dissenting]He voted with the majority in "

Cooper v. Aaron ",ussc|358|1|1958] compelling defiant officials inArkansas todesegregate public schools. He joined the opinion in "Gomillion v. Lightfoot", ussc|364|339|1960] which declared that states could not redraw political boundaries in order to reduce the voting power of African-Americans. Moreover, he concurred in "Loving v. Virginia ",ussc|388|1|1967, Harlan, J., concurring] which struck down state laws that banned interracial marriage.Due Process Clause

Justice Harlan advocated a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. He subscribed to the doctrine that the clause not only provided procedural guarantees, but also protected a wide range of fundamental rights, including those that were not specifically mentioned in the text of the Constitution. (See substantive due process.) However, as Justice

Byron White noted in his dissenting opinion in "Moore v. East Cleveland", "no one was more sensitive than Mr. Justice Harlan to any suggestion that his approach to the Due Process Clause would lead to judges 'roaming at large in the constitutional field.'" Under Harlan's approach, judges would be limited in the Due Process area by "respect for the teachings of history, solid recognition of the basic values that underlie our society, and wise appreciation of the great roles that the doctrines of federalism and separation of powers have played in establishing and preserving American freedoms."ussc|381|479|1965, Harlan, J., concurring in the judgment, p.501–502]Harlan set forth his interpretation in an often cited dissenting opinion to "

Poe v. Ullman ",ussc|367|497|1961, Harlan, J., dissenting] which involved a challenge to aConnecticut law banning the use ofcontraceptive s. The Supreme Court dismissed the case on technical grounds, holding that the case was not ripe for adjudication. Justice Harlan dissented from the dismissal, suggesting that the Court should have considered the merits of the case. Thereafter, he indicated his support for a broad view of the due process clause's reference to "liberty." He wrote, "This 'liberty' is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints." He suggested that the due process clause encompassed a right to privacy, and concluded that a prohibition on contraception violated this right.The same law was challenged again in "

Griswold v. Connecticut ".ussc|381|479|1965, Harlan, J., concurring] This time, the Supreme Court agreed to consider the case, and concluded that the law violated the Constitution. However, the decision was based not on the due process clause, but on the argument that a right to privacy was found in the "penumbra s" of other provisions of the Bill of Rights. Justice Harlan concurred in the result, but criticized the Court for relying on the Bill of Rights in reaching its decision. "The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment stands," he wrote, "on its own bottom." The Supreme Court would later adopt Harlan's approach, relying on the due process clause rather than the penumbras of the Bill of Rights in right to privacy cases such as "Roe v. Wade ",ussc|410|113|1972] and "Lawrence v. Texas ".ussc|539|558|2003]Harlan's interpretation of the Due Process Clause attracted the criticism of Justice Black, who rejected the idea that the Clause included a "substantive" component, considering this interpretation unjustifiably broad and historically unsound. The Supreme Court has sided with Harlan, and has continued to apply the doctrine of substantive due process in a wide variety of cases.cite book|last=Yarbrough|first=Tinsley E.|title=Mr. Justice Black and his critics|year=1989|publisher=Duke University Press|chapter=Chapter3, The bill of rights and the states|isbn=978-0822308669]

Incorporation

Justice Harlan was strongly opposed to the theory that the Fourteenth Amendment "incorporated" the Bill of Rights—that is, made the provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states. His opinion on the matter was opposite to that of his grandfather, who supported the full incorporation of the Bill of Rights.cite journal|last=Wildenthal|first=Bryan H.|title=The Road to Twining: Reassessing the Disincorporation of the Bill of Rights|journal=Ohio State Law Journal|volume=61|year=2000|pages=1457–1496|format=pdf| url=http://moritzlaw.osu.edu/lawjournal/issues/volume61/number4/wildenthal.pdf] When it was originally ratified, the Bill of Rights was binding only upon the federal government, as the Supreme Court ruled in "

Barron v. Baltimore ".ussc|32|243|1833] Some jurists argued that the Fourteenth Amendment made the entirety of the Bill of Rights binding upon the states as well. Harlan, however, rejected this doctrine, which he called "historically unfounded" in his "Griswold" concurrence.Instead, Justice Harlan believed that the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause only protected "fundamental" rights. Thus, if a guarantee of the Bill of Rights was "fundamental" or "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty," Harlan agreed that it applied to the states as well as the federal government. Thus, for example, Harlan believed that the First Amendment's free speech clause applied to the states, but that the Fifth Amendment's self incrimination clause did not.

Harlan's approach was largely similar to that of Justices

Benjamin Cardozo andFelix Frankfurter . It drew criticism from Justice Black, a proponent of the total incorporation theory. Black claimed that the process of identifying some rights as more "fundamental" than others was largely arbitrary, and depended on each Justice's personal opinions.The Supreme Court has sided with Harlan, holding that only "fundamental" Bill of Rights guarantees were applicable against the states. However, under Chief Justice Earl Warren during the 1960s, an increasing number of rights were deemed sufficiently fundamental for incorporation. (Harlan regularly dissented from these rulings.) Hence, majority of provisions of the Bill of Rights have been extended to the states; the only exceptions are the Second Amendment, the Third Amendment, the grand jury clause of the Fifth Amendment, the Seventh Amendment, the excessive bail provision of the Eighth Amendment, the Ninth Amendment, and the Tenth Amendment. Thus, although the Supreme Court has agreed with Harlan's general reasoning, the end result of its jurisprudence is very different from what Harlan advocated.cite web|last=Cortner|first=Richard|title=The Nationalization of the Bill of Rights: An Overview|url=http://www.apsanet.org/imgtest/Nationalization_Bill.pdf|format=pdf|year=1985|publisher=American Political Science Association and American Historical Association|accessdate=2008-08-19]

First Amendment

Justice Harlan concurred in many of the Warren Court's landmark decisions relating to the

separation of church and state . For instance, he voted in favor of the Court's ruling that the states could not use religious tests as qualifications for public office in "Torcaso v. Watkins ".ussc|367|488|1961] He joined in "Engel v. Vitale ",ussc|370|421|1962] which declared that it was unconstitutional for states to require the recitation of official prayers in public schools. In "Epperson v. Arkansas ",ussc|393|97|1968] similarly, he voted to strike down an Arkansas law banning the teaching ofevolution .In many cases, Harlan took a fairly broad view of First Amendment rights such as the freedom of speech and of the press, but felt that the guarantees of the First Amendment applied more stringently to the federal government than the states because of the federalism principle he believed implicit in the Constitution.cite journal|last=O'Neil|first=Robert M.|title=The neglected first amendment jurisprudence of the second justice Harlan|journal=NYU annual survey of American law|volume=58|year=2001|pages=57–66| url=http://www1.law.nyu.edu/pubs/annualsurvey/documents/58%20N.Y.U.%20Ann.%20Surv.%20Am.%20L.%2057%20(2001).pdf] He concurred in "

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan ",ussc|376|254|1964] which required public officials suing newspapers for libel to prove that the publisher had acted with "actual malice ." This stringent standard made it much more difficult for public officials to win libel cases. However, Harlan did not go as far as Justices Hugo Black andWilliam O. Douglas , who suggested that all libel laws were unconstitutional. In "Street v. New York",ussc|394|576|1969] Harlan delivered the opinion of the court, ruling that the government could not punish an individual for insulting theAmerican flag . In 1969 he noted that the Supreme Court had consistently "rejected all manner of prior restraint on publication." [Floyd Abrams , "Speaking Freely", published byViking Press , Page 15–16.]Harlan also penned the majority opinion in "

Cohen v. California ",ussc|403|15|1971] holding that wearing ajacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" was speech protected by the First Amendment. In the "Cohen" opinion, Harlan famously wrote "one man'svulgarity is another's lyric," a quote that was later denounced byRobert Bork as "moral relativism ". [http://ctlibrary.com/1198 Conversations: Robert Bork says, Give me liberty, but don't give me filth]Christianity Today ]Moreover, Justice Harlan believed that federal laws censoring "obscene" publications violated the free speech clause. Thus, he dissented from "

Roth v. United States ",ussc|354|476|1957, Harlan, J., dissenting] in which the Supreme Court upheld the validity of a federal obscenity law. At the same time, Harlan did not believe that the Constitution prevented the states from censoring obscenity. He explained in his "Roth" dissent:The danger is perhaps not great if the people of one State, through their legislature, decide that "

Lady Chatterley's Lover " goes so far beyond the acceptable standards of candor that it will be deemed offensive and non-sellable, for the State next door is still free to make its own choice. At least we do not have one uniform standard. But the dangers to free thought and expression are truly great if the Federal Government imposes a blanket ban over the Nation on such a book. [...] The fact that the people of one State cannot read some of the works ofD. H. Lawrence seems to me, if not wise or desirable, at least acceptable. But that no person in the United States should be allowed to do so seems to me to be intolerable, and violative of both the letter and spirit of the First Amendment.Justice Harlan is credited for the establishing that the First Amendement protects the freedom of association. In "

NAACP v. Alabama ",ussc|357|449|1958] Justice Harlan delivered the opinion of the court, invalidating an Alabama law that required theNAACP to disclose membership lists. However he did not believe that individuals were entitled to exercise their First Amendment rights wherever they pleased. He joined in "Adderley v. Florida",ussc|385|39|1966] which controversially upheld a trespassing conviction for protesters who demonstrated on government property. He dissented from "Brown v. Louisiana ",ussc|383|131|1966] in which the Court held that protesters were entitled to engage in a sit-in at a public library. Likewise, he disagreed with "Tinker v. Des Moines ",ussc|393|503|1969] in which the Supreme Court ruled that students had the right to wear armbands (as a form of protest) in public schools.Criminal procedure

During the 1960s the Warren Court made a series of rulings expanding the rights of criminal

defendant s. In some instances, Justice Harlan concurred in the result; "Gideon v. Wainwright ", ussc|372|335|1963] is one notable example. In many other cases, however, Harlan found himself in dissent. He was usually joined by the other moderate members of the Court: JusticesPotter Stewart ,Tom Clark , andByron White .cite journal|last=Vasicko|first=Sally Jo|title=John Marshall Harlan: neglected advocate of federalism|journal=Modern Age|year=1980|volume=24|issue=4|pages=387–395|url=http://www.mmisi.org/ma/24_04/vasicko.pdf|format=pdf]Most notably, Harlan dissented from Supreme Court rulings restricting

interrogation techniques used by law enforcement officers. For example, he dissented from the Court's holding in "Escobedo v. Illinois ", ussc|378|478|1964] that the police could not refuse to honor a suspect's request to consult with his lawyer during an interrogation. Harlan called the rule "ill-conceived" and suggested that it "unjustifiably fetters perfectly legitimate methods of criminal law enforcement." He disagreed with "Miranda v. Arizona ",ussc|384|436|1965, Harlan, J., dissenting] which required law enforcement officials to warn a suspect of his rights before questioning him (seeMiranda warning ). He closed his dissenting opinion with a quotation from his predecessor, JusticeRobert Jackson : "This Court is forever adding new stories to the temples of constitutional law, and the temples have a way of collapsing when one story too many is added."In "Gideon v. Wainwright", Justice Harlan agreed that the Constitution required states to provide attorneys for defendants who could not afford their own counsel. However, he believed that this requirement applied only at trial, and not on appeal; thus, he dissented from "Douglas v. California".ussc|372|353|1963]

Harlan wrote the majority opinion "

Leary v. United States "—a case that declaredMarijuana Tax Act unconstitutional based on the Fifth Amendment protection againstself-incrimination .ussc|395|6|1969]Justice Harlan's concurrence in "

Katz v. United States "ussc|389|347|1967] is often cited for setting forth the test for determining whether government conduct constituted a search. In this case the Supreme Court held that eavesdropping of the petitioner's telephone conversation constituted a search in the meaning of the fourth amendement and thus required a warrant. According to Justice Harlan, there is a two-part requirement for a search: 1. That the individual have a subjective expectation of privacy; and 2. That the individual's expectation of privacy is "one that society is prepared to recognize as 'reasonable.'"Voting rights

Justice Harlan rejected the theory that the Constitution enshrined the so-called "

one man, one vote " principle, or the principle that legislative districts must be roughly equal in population. In this regard, he shared the views of Justice Felix Frankfurter, who in "Colegrove v. Green "ussc|328|549|1946] admonished the courts to stay out of the "political thicket" ofreapportionment . The Supreme Court, however, disagreed with Harlan in a series of rulings during the 1960s. The first case in this line of rulings was "Baker v. Carr ".ussc|369|186|1962] The Court ruled that the courts had juristiction overmalapportionment issues and therefore were entitled to review the validity of district boundaries. Harlan, however, dissented, on the grounds that the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate that malapportionment violated their individual rights.Then, in "

Wesberry v. Sanders ",ussc|376|1|1964, Harlan, J., dissenting] the Supreme Court, relying on the Constitution's requirement that theUnited States House of Representatives be elected "by the People of the several States," ruled that congressional districts in any particular state must be approximately equal in population. Harlan vigorously dissented, writing, "I had not expected to witness the day when the Supreme Court of the United States would render a decision which casts grave doubt on the constitutionality of the composition of the House of Representatives. It is not an exaggeration to say that such is the effect of today's decision." He proceeded to argue that the Court's decision was inconsistent with both the history and text of the Constitution; moreover, he claimed that only Congress, not the judiciary, had the power to require congressional districts with equal populations.This Court, limited in function in accordance with that premise, does not serve its high purpose when it exceeds its authority, even to satisfy justified impatience with the slow workings of the political process. For when, in the name of constitutional interpretation, the Court adds something to the Constitution that was deliberately excluded from it, the Court, in reality, substitutes its view of what should be so for the amending process.

For similar reasons, Harlan dissented from "Carrington v. Rash",ussc|380|89|1965, Harlan, J., dissenting] in which the Court held that voter qualifications were subject to scrutiny under the equal protection clause. He claimed in his dissent, "the Court totally ignores, as it did in last Term's reapportionment cases [...] all the history of the Fourteenth Amendment and the course of judicial decisions which together plainly show that the Equal Protection Clause was not intended to touch state electoral matters." Similarly, Justice Harlan disagreed with the Court's ruling in "

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections ",ussc|383|663|1966] invalidating the use of thepoll tax as a qualification to vote.Retirement and death

John M. Harlan's health began to deteriorate towards the end of his career. His eyesight began to fail during the late 1960s.cite book|last= Dean|first= John|title=The Rehnquist Choice|origdate= |origyear= |origmonth= |url= |format= |date=2001 |chapter=2 |publisher=Free Press] Gravely ill, he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971.

Harlan died from

spinal cancer three months later, on December 29, 1971. He was buried at the Emmanuel Church Cemetery inWeston, Connecticut .cite web|url=http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=447|title=John Marshall Harlan|accessdate=2008-08-16|publisher=Find a Grave] PresidentRichard Nixon considered nominatingMildred Lillie , a California appeals court judge, to fill the vacant seat; Lillie would have been the first female nominee to the Supreme Court. However, Nixon decided against Lillie's nomination after theAmerican Bar Association found Lillie to be unqualified.cite web|author=By a MetNews staff writer|publisher=Metropolitan News-Enterprise|title=Justice Lillie Remembered for Hard Work, Long Years of Service|url=http://www.metnews.com/articles/lill103102.htm|accessdate=2008-08-16|date=October 31, 2002] Thereafter, Nixon nominatedWilliam Rehnquist (the future Chief Justice), who was confirmed by the Senate.Harlan's extensive professional and Supreme Court papers were donated to

Princeton University , where they are housed at the Seely G. Mudd Manuscript Library and open to research.References

Additional reading

*cite journal|last=Dorsen|first=Norman|coauthors=Newcomb, Amela Ames|year=2002|title=John Marshall Harlan II: Remembrances by his Law Clerks|journal=Journal of Supreme Court History|volume=27|issue=2|pages=138–175

*cite book|author=Shapiro, David L.|year=1969|title=The Evolution of a Judicial Philosophy: Selected Opinions and Papers of Justice John M. Harlan|location=Cambridge, MA|publisher=Harvard University Press

*cite book|last=Mayer|first=Martin|title=Emory Buckner|year=1968|location=New York|publisher=Harper & Row (Harlan arranged for Mayer to write this book about his mentorEmory Buckner and wrote the book's Introduction.)

*cite book|last=Yarbrough|first=Tinsley E.|year=1992|title=John Marshall Harlan : Great Dissenter of the Warren Court|location= New York|publisher=Oxford University PressExternal links

* [http://www.supremecourthistory.org/02_history/subs_timeline/images_associates/075.html Supreme Court Historical Society. "John Marshall Harlan II."]

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.