- Endometriosis

-

Endometriosis Classification and external resources

ICD-10 N80 ICD-9 617.0 OMIM 131200 DiseasesDB 4269 MedlinePlus 000915 eMedicine med/3419 ped/677 emerg/165 MeSH D004715 Endometriosis (from endo, "inside", and metra, "womb") is a gynecological medical condition in which cells from the lining of the uterus (endometrium) appear and flourish outside the uterine cavity, most commonly on the ovaries. The uterine cavity is lined by endometrial cells, which are under the influence of female hormones. These endometrial-like cells in areas outside the uterus (endometriosis) are influenced by hormonal changes and respond in a way that is similar to the cells found inside the uterus. Symptoms often worsen with the menstrual cycle.

Endometriosis is typically seen during the reproductive years; it has been estimated that endometriosis occurs in roughly 5-10% of women.[1] Symptoms may depend on the site of active endometriosis. Its main but not universal symptom is pelvic pain in various manifestations. Endometriosis is a common finding in women with infertility.[2]

Contents

Signs and symptoms

Pelvic pain

A major symptom of endometriosis is recurring pelvic pain. The pain can be mild to severe cramping that occurs on both sides of the pelvis, in the lower back and rectal area, and even down the legs. The amount of pain a woman feels correlates poorly with the extent or stage (1 through 4) of endometriosis, with some women having little or no pain despite having extensive endometriosis or endometriosis with scarring, while, on the other hand, other women may have severe pain even though they have only a few small areas of endometriosis.[3] Symptoms of endometriosis-related pain may include:[4]

- dysmenorrhea – painful, sometimes disabling cramps during menses; pain may get worse over time (progressive pain), also lower back pains linked to the pelvis

- chronic pelvic pain – typically accompanied by lower back pain or abdominal pain

- dyspareunia – painful sex

- dysuria – urinary urgency, frequency, and sometimes painful voiding

Throbbing, gnawing, and dragging pain to the legs are reported more commonly by women with endometriosis.[5] Compared with women with superficial endometriosis, those with deep disease appear to be more likely to report shooting rectal pain and a sense of their insides being pulled down.[5] Individual pain areas and pain intensity appears to be unrelated to the surgical diagnosis, and the area of pain unrelated to area of endometriosis.[5]

Fertility

Many women with infertility may have endometriosis. As endometriosis can lead to anatomical distortions and adhesions (the fibrous bands that form between tissues and organs following recovery from an injury), the causality may be easy to understand; however, the link between infertility and endometriosis remains enigmatic when the extent of endometriosis is limited.[6] It has been suggested that endometriotic lesions release factors which are detrimental to gametes or embryos, or, alternatively, endometriosis may more likely develop in women who fail to conceive for other reasons and thus be a secondary phenomenon; for this reason it is preferable to speak of endometriosis-associated infertility[7] in such cases. In some cases it can take a woman with endometriosis 7-10 years to conceive her first child, to most couples this can be stressful and daunting.

Other

Other symptoms may be present, including:

- Constipation[5]

- chronic fatigue[8]

In addition to pain during menstruation, the pain of endometriosis can occur at other times of the month. There can be pain with ovulation, pain associated with adhesions, pain caused by inflammation in the pelvic cavity, pain during bowel movements and urination, during general bodily movement i.e. exercise, pain from standing or walking, and pain with intercourse. But the most desperate pain is usually with menstruation and many women dread having their periods. Pain can also start a week before menses, during and even a week after menses, or it can be constant. There is no known cure for endometriosis. [9]

Complications

Complications of endometriosis include:

- Internal scarring

- Adhesions[10]

- Pelvic cysts

- Chocolate cyst of ovaries

- Ruptured cyst

- Bowel obstruction

Infertility can be related to scar formation and anatomical distortions due to the endometriosis; however, endometriosis may also interfere in more subtle ways: cytokines and other chemical agents may be released that interfere with reproduction.

Other complications of endometriosis include bowel and ureteral obstruction resulting from pelvic adhesions. Also, peritonitis from bowel perforation can occur.

Ovarian endometriosis may complicate pregnancy by decidualization, abscess and/or rupture.[11] It is the most common adnexal mass detected during pregnancy, being present in 0.52% of deliveries as studied in the period 2002 to 2007.[11] Still, ovarian endometriosis during pregnancy can be safely observed conservatively.[11]

Pleural implantations are associated with recurrent right pneumothoraces at times of menses, termed catamenial pneumothorax.

Risk factors

Genetics

Genetic predisposition plays a role in endometriosis.[12] It is well recognized that daughters or sisters of patients with endometriosis are at higher risk of developing endometriosis themselves; for example, low progesterone levels may be genetic, and may contribute to a hormone imbalance. There is an about 10-fold increased incidence in women with an affected first-degree relative.[13] One study found that in female siblings of patients with endometriosis the relative risk of endometriosis is 5.7:1 versus a control population.[14]

It has been proposed that endometriosis results from a series of multiple hits within target genes, in a mechanism similar to the development of cancer.[12] In this case, the initial mutation may be either somatic or heritable.[12]

Individual genomic changes (found by genotyping) that have been associated with endometriosis include:

In addition, there are many findings of altered gene expression and epigenetics, but both of these can also be a secondary result of, for example, environmental factors and altered metabolism. Examples of altered gene expression include that of miRNAs.[12]

Environmental

There is a growing suspicion that environmental factors may cause endometriosis, specifically some plastics and cooking with certain types of plastic containers with microwave ovens.[17] Dioxin exposure has been found a very likely cause of endometriosis in one well known study by The Endometriosis association that found that 79% of monkeys developed Endometriosis after receiving doses of dioxin.[18] Other sources suggest that pesticides and hormones in our food cause a hormone imbalance.

- Tobacco smoking: The risk of endometriosis has been reported to be reduced in smokers.[19] Smoking causes decreased estrogens with increased breakthrough bleeding and shortened luteal phases. Smokers have an earlier than normal (by about 1.5–3 years) menopause which suggests that there is some toxic effect of smoking on the follicles directly. Chemically, nicotine has been shown to concentrate in cervical mucous and metabolites have been found in follicular fluid and been associated with delayed follicular growth and maturation. Finally, there is some effect on tubal motility because smoking is associated with an increased incidence of ectopic pregnancy as well as an increased spontaneous abortion rate.

Aging

Aging brings with it many effects that may reduce fertility. Depletion over time of ovarian follicles affects menstrual regularity. Endometriosis has more time to produce scarring of the ovary and tubes so they cannot move freely or it can even replace ovarian follicular tissue if ovarian endometriosis persists and grows. Leiomyomata (fibroids) can slowly grow and start causing endometrial bleeding that disrupts implantation sites or distorts the endometrial cavity which affects carrying a pregnancy in the very early stages. Abdominal adhesions from other intraabdominal surgery, or ruptured ovarian cysts can also affect tubal motility needed to sweep the ovary and gather an ovulated follicle (egg).

Endometriosis in postmenopausal women does occur and has been described as an aggressive form of this disease characterized by complete progesterone resistance and extraordinarily high levels of aromatase expression.[20] In less common cases, girls may have endometriosis symptoms before they even reach menarche.[21][22]

Pathophysiology

While the exact cause of endometriosis remains unknown, many theories have been presented to better understand and explain its development. These concepts do not necessarily exclude each other. The pathophysiology of endometriosis is likely to be multifactorial and to involve an interplay between several factors.[12]

Broadly, the aspects of the pathophysiology can basically be classified as underlying predisposing factors, metabolic changes, formation of ectopic endometrium, and generation of pain and other effects. It is not certain, however, to what degree predisposing factors lead to metabolic changes and so on, or if metabolic changes or formation of ectopic endometrium is the primary cause. Also, there are several theories within each category, but the uncertainty over what is a cause versus what is an effect when considered in relation to other aspects is as true for any individual entry in the pathophysiology of endometriosis.[12]

Also, pathogenic mechanisms appear to differ in the formation of distinct types of endometriotic lesion, such as peritoneal, ovarian and rectovaginal lesions.[12]

Metabolic changes

Endometriosis correlates with abnormal amounts of multiple substances, possibly indicating a causative link in its pathogenesis, although correlation does not imply causation:

- Endometrial cells in women with endometriosis demonstrate increased adherence to peritoneal cells and increased expression of splice variants of CD44, a cell-surface protein involved in cell adhesions.[23]

- The matrix metalloproteinases MMP-1 and MMP-2 are also increased, and appear to be major factors involved in the invasion of endometrium into the peritoneum and in vascularization of endometriosis.[24]

- Endometriosis patients also have elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptors-1 and -2 (sVEGFR-1 and -2) and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2).[25] IL-4 may induce angiogenesis in endometriosis by inducing expression of eotaxin.[26]

- Increased oxidative stress is also implicated in the pathophysiology of endometriosis, as well as 8-iso-PGF2α and oxysterols, being potential causative links in this oxidative stress.[27]

Endometriosis is a condition that is estrogen-dependent and thus seen primarily during the reproductive years. In experimental models, estrogen is necessary to induce or maintain endometriosis. Medical therapy is often aimed at lowering estrogen levels to control the disease. Additionally, the current research into aromatase, an estrogen-synthesizing enzyme, has provided evidence as to why and how the disease persists after menopause and hysterectomy.

Formation of ectopic endometrium

The main theories for the formation of ectopic endometrium are retrograde menstruation, müllerianosis, coelomic metaplasia and transplantation, each further described below.

Retrograde menstruation

The theory of retrograde menstruation is the most widely accepted theory for the formation of ectopic endometrium in endometriosis.[12] It suggests that during a woman's menstrual flow, some of the endometrial debris exits the uterus through the fallopian tubes and attaches itself to the peritoneal surface (the lining of the abdominal cavity) where it can proceed to invade the tissue as endometriosis.[12]

While most women may have some retrograde menstrual flow, typically their immune system is able to clear the debris and prevent implantation and growth of cells from this occurrence. However, in some patients, endometrial tissue transplanted by retrograde menstruation may be able to implant and establish itself as endometriosis. Factors that might cause the tissue to grow in some women but not in others need to be studied, and some of the possible causes below may provide some explanation, e.g., hereditary factors, toxins, or a compromised immune system. It can be argued that the uninterrupted occurrence of regular menstruation month after month for decades is a modern phenomenon, as in the past women had more frequent menstrual rest due to pregnancy and lactation.

Retrograde menstruation alone is not able to explain all instances of endometriosis, and it needs additional factors such as genetic or immune differences to account for the fact that many women with retrograde menstruation do not have endometriosis. Research is focusing on the possibility that the immune system may not be able to cope with the cyclic onslaught of retrograde menstrual fluid. In this context there is interest in studying the relationship of endometriosis to autoimmune disease, allergic reactions, and the impact of toxins.[28][29] It is still unclear what, if any, causal relationship exists between toxins, autoimmune disease, and endometriosis

In addition, at least one study found that endometriotic lesions are biochemically very different from artificially transplanted ectopic tissue.[30] The latter finding, however, can in turn be explained by that the cells that establish endometrial lesions are not of the main cell type in ordinary endometrium, but rather of a side population cell type, as supported by exhibitition of a side population phenotype upon staining with Hoechst dye and by flow cytometric analysis.[12]

In rare cases where imperforate hymen does not resolve itself prior to the first menstrual cycle and goes undetected, blood and endometrium are trapped within the uterus of the patient until such time as the problem is resolved by surgical incision. Many health care practitioners never encounter this defect, and due to the flu-like symptoms it is often misdiagnosed or overlooked until multiple menstrual cycles have passed. By the time a correct diagnosis has been made, endometrium and other fluids have filled the uterus and fallopian tubes with results similar to retrograde menstruation resulting in endometriosis. The initial stage of endometriosis may vary based on the time elapsed between onset and surgical procedure.

The theory of retrograde menstruation as a cause of endometriosis was first proposed by John A. Sampson.

Other theories of endometrial formation

- Müllerianosis: A competing theory states that cells with the potential to become endometrial are laid down in tracts during embryonic development and organogenesis. These tracts follow the female reproductive (Mullerian) tract as it migrates caudally (downward) at 8–10 weeks of embryonic life. Primitive endometrial cells become dislocated from the migrating uterus and act like seeds or stem cells. This theory is supported by foetal autopsy.[31]

- Coelomic metaplasia: This theory is based on the fact that coelomic epithelium is the common ancestor of endometrial and peritoneal cells and hypothesizes that later metaplasia (transformation) from one type of cell to the other is possible, perhaps triggered by inflammation.[1] This theory is further supported by laboratory observation of this transformation.[32]

- Transplantation: It is accepted that in specific patients endometriosis can spread directly. Thus endometriosis has been found in abdominal incisional scars after surgery for endometriosis. It can also grow invasively into different tissue layers, i.e., from the cul-de-sac into the vagina. On rare occasions endometriosis may be transplanted by blood or by the lymphatic system into peripheral organs such as the lungs and brain.[citation needed]

It appears that that up to 37% of the microvascular endothelium of ectopic endometrial tissue originates from endothelial progenitor cells, which result in de novo formation of microvessels by the process vasculogenesis rather than the conventional process of angiogenesis.[33]

Generation of pain

The way endometriosis causes pain is the subject of much research. Because many women with endometriosis feel pain during or around their periods and may spill further menstrual flow into the pelvis with each menstruation, some researchers are trying to reduce menstrual events in patients with endometriosis.

Endometriosis lesions react to hormonal stimulation and may "bleed" at the time of menstruation. The blood accumulates locally, causes swelling, and triggers inflammatory responses with the activation of cytokines. It is thought that this process may cause pain.

Pain can also occur from adhesions (internal scar tissue) binding internal organs to each other, causing organ dislocation. Fallopian tubes, ovaries, the uterus, the bowels, and the bladder can be bound together in ways that are painful on a daily basis, not just during menstrual periods.

Also, endometriotic lesions can develop their own nerve supply, thereby creating a direct and two-way interaction between lesions and the central nervous system, potentially producing a variety of individual differences in pain that can, in some women, become independent of the disease itself.[3]

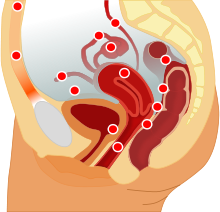

Localization

Most endometriosis is found on these structures in the pelvic cavity:[citation needed]

- Ovaries (the most common site)

- Fallopian tubes

- The back of the uterus and the posterior cul-de-sac

- The front of the uterus and the anterior cul-de-sac

- Uterine ligaments such as the broad or round ligament of the uterus

- Pelvic and back wall

- Intestines, most commonly the rectosigmoid

- Urinary bladder and ureters

Bowel endometriosis affects approximately 10% of women with endometriosis, and can cause severe pain with bowel movements.[citation needed]

Endometriosis may spread to the cervix and vagina or to sites of a surgical abdominal incision.[citation needed]

Endometriosis may also present with skin lesions in cutaneous endometriosis.

Less commonly lesions can be found on the diaphragm. Diaphragmatic endometriosis is rare, almost always on the right hemidiaphragm, and may inflict cyclic pain of the right shoulder just before and during menses. Rarely, endometriosis can be extraperitoneal and is found in the lungs and CNS.[34]

Diagnosis

A health history and a physical examination can in many patients lead the physician to suspect endometriosis. Surgery is the gold standard in diagnosis. However, in the United States most insurance plans will not cover surgical diagnosis unless the patient has already attempted to become pregnant and failed.

Use of imaging tests may identify endometriotic cysts or larger endometriotic areas. It also may identify free fluid often within the cul-de-sac. The two most common imaging tests are ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Normal results on these tests do not eliminate the possibility of endometriosis. Areas of endometriosis are often too small to be seen by these tests.

Endoscopic image of endometriotic lesions in the Pouch of Douglas and on the right sacrouterine ligament.

Endoscopic image of endometriotic lesions in the Pouch of Douglas and on the right sacrouterine ligament.

The only way to diagnose endometriosis is by laparoscopy or other types of surgery with lesion biopsy.[citation needed] The diagnosis is based on the characteristic appearance of the disease, and should be corroborated by a biopsy. Surgery for diagnoses also allows for surgical treatment of endometriosis at the same time.

Although doctors can often feel the endometrial growths during a pelvic exam, and these symptoms may be signs of endometriosis, diagnosis cannot be confirmed without performing a laparoscopic procedure. To the eye, lesions can appear dark blue. powder-burn black, red, white, yellow, brown or non-pigmented. Lesions vary in size. Some within the pelvis walls may not be visible to the eye, as normal-appearing peritoneum of infertile women reveals endometriosis on biopsy in 6–13% of cases.[35] Early endometriosis typically occurs on the surfaces of organs in the pelvic and intra-abdominal areas. Health care providers may call areas of endometriosis by different names, such as implants, lesions, or nodules. Larger lesions may be seen within the ovaries as ovarian endometriomas or "chocolate cysts", "chocolate" because they contain a thick brownish fluid, mostly old blood.

Often the symptoms of ovarian cancer are identical to those of endometriosis. If a misdiagnosis of endometriosis occurs due to failure to confirm diagnosis through laparoscopy, early diagnosis of ovarian cancer, which is crucial for successful treatment, may have been missed.[36]

If surgery is not performed, then a diagnosis of exclusion process is used. This means that all of the other plausible causes of pelvic pain are ruled out. For example, internal hernias are difficult to identify in women, and misdiagnosis with endometriosis is very common. One cause of misdiagnosis is that when the woman lies down flat on an examination table, all of the medical signs of the hernia disappear, but the woman typically has tenderness and other symptoms associated with endometriosis in a pelvic exam. The hernia can typically only be detected when symptoms are present, so diagnosis requires positioning the woman's body in a way that provokes symptoms.[37]

Staging

Surgically, endometriosis can be staged I–IV (Revised Classification of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine).[38] The process is a complex point system that assesses lesions and adhesions in the pelvic organs, but it is important to note staging assesses physical disease only, not the level of pain or infertility. A patient with Stage I endometriosis may have little disease and severe pain, while a patient with Stage IV endometriosis may have severe disease and no pain or vice versa. In principle the various stages show these findings:

- Stage I (Minimal)

- Findings restricted to only superficial lesions and possibly a few filmy adhesions

- Stage II (Mild)

- In addition, some deep lesions are present in the cul-de-sac

- Stage III (Moderate)

- As above, plus presence of endometriomas on the ovary and more adhesions.

- Stage IV (Severe)

- As above, plus large endometriomas, extensive adhesions.

Endometrioma on the ovary of any significant size (Approx. 2 cm +) must be removed surgically because hormonal treatment alone will not remove the full endometrioma cyst, which can progress to acute pain from the rupturing of the cyst and internal bleeding. Endometrioma is sometimes misdiagnosed as ovarian cysts.

Markers

An area of research is the search for endometriosis markers. These markers are substances made by or in response to endometriosis that health care providers can measure in biopsies, in the blood or urine. Detection of such a marker may result in an earlier diagnosis of endometriosis than can be made by the rather non-specific symptoms, and may replace the invasive surgical procedures to verify the disease.[39] A biomarker could also be used to identify early signs of therapeutic efficacy or disease recurrence, as symptomatic relief or aggravation usually is hard to quantify.[39] However, as the benefits of treating women with asymptomatic endometriosis are unclear, it is likely that any biomarker would be used only to investigate women with symptoms suggestive of endometriosis.[39] Therefore, a prospective biomarker needs to distinguish women with endometriosis from women with similar presentations (for example, dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain or subfertility).[39]

A systematic review in 2010 of essentially all proposed biomarkers for endometriosis in serum, plasma and urine came to the conclusion that none of them have been clearly shown to be of clinical use, although some appear to be promising.[39] Another review in 2011 identified several putative biomarkers upon biopsy, including findings of small sensory nerve fibers or defectively expressed β3 integrin subunit.[40]

The one biomarker that has been used in clinical practice over the last 20 years is CA-125.[39] However, its performance in diagnosing endometriosis is low, even though it shows some promise in detecting more severe disease.[39] CA-125 levels appear to fall during endometriosis treatment, but has not shown a correlation with disease response.[39]

Research is also being conducted on potential genetic markers associated with endometriosis so that a saliva-based diagnostic may replace surgical procedures for basic diagnosis.[41] However, this research remains very preliminary.

It has been postulated a future diagnostic tool for endometriosis will consist of a panel of several biomarkers, including both substance concentrations and genetic predisposition.[39]

Histopathology

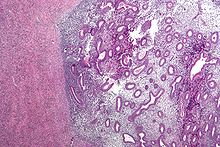

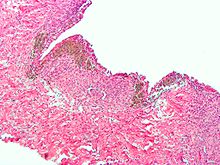

Micrograph of the wall of an endometrioma. All features of endometriosis are present (endometrial glands, endometrial stroma and hemosiderin-laden macrophages. H&E stain.

Micrograph of the wall of an endometrioma. All features of endometriosis are present (endometrial glands, endometrial stroma and hemosiderin-laden macrophages. H&E stain.

Typical endometriotic lesions show histopathologic features similar to endometrium, namely endometrial stroma, endometrial epithelium, and glands that respond to hormonal stimuli. Older lesions may display no glands but hemosiderindeposits as residual.

Treatments

While there is no cure for endometriosis, in many people menopause (natural or surgical) will abate the process. In patients in the reproductive years, endometriosis is merely managed: the goal is to provide pain relief, to restrict progression of the process, and to restore or preserve fertility where needed. In younger women with unfulfilled reproductive potential, surgical treatment attempts to remove endometrial tissue and preserving the ovaries without damaging normal tissue.

In general, the diagnosis of endometriosis is confirmed during surgery, at which time ablative steps can be taken. Further steps depend on circumstances: patients without infertility can be managed with hormonal medication that suppress the natural cycle and pain medication, while infertile patients may be treated expectantly after surgery, with fertility medication, or with IVF.

Sonography is a method to monitor recurrence of endometriomas during treatments.

Treatments for endometriosis in women who do not wish to become pregnant include:

Hormonal medication

- Progesterone or Progestins: Progesterone counteracts estrogen and inhibits the growth of the endometrium. Such therapy can reduce or eliminate menstruation in a controlled and reversible fashion. Progestins are chemical variants of natural progesterone.

- Avoiding products with xenoestrogens, which have a similar effect to naturally produced estrogen and can increase growth of the endometrium.

- Hormone contraception therapy: Oral contraceptives reduce the menstrual pain associated with endometriosis.[42] They may function by reducing or eliminating menstrual flow and providing estrogen support. Typically, it is a long-term approach. Recently Seasonale was FDA approved to reduce periods to 4 per year. Other OCPs have however been used like this off label for years. Continuous hormonal contraception consists of the use of combined oral contraceptive pills without the use of placebo pills, or the use of NuvaRing or the contraceptive patch without the break week. This eliminates monthly bleeding episodes.

- Danazol (Danocrine) and gestrinone are suppressive steroids with some androgenic activity. Both agents inhibit the growth of endometriosis but their use remains limited as they may cause hirsutism and voice changes.

- Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonist: These agents work by increasing the levels of GnRH. Consistent stimulation of the GnRH receptors results in downregulation, inducing a profound hypoestrogenism by decreasing FSH and LH levels. While effective in some patients, they induce unpleasant menopausal symptoms, and over time may lead to osteoporosis. To counteract such side effects some estrogen may have to be given back (add-back therapy). These drugs can only be used for six months at a time.

- Lupron depo shot is a GnRH agonist and is used to lower the hormone levels in the woman's body to prevent or reduce growth of endometriosis. The injection is given in 2 different doses: a 3 month course of monthly injections, each with the dosage of (11.25 mg); or a 6 month course of monthly injections, each with the dosage of (3.75 mg).[43]

- Aromatase inhibitors are medications that block the formation of estrogen and have become of interest for researchers who are treating endometriosis.[44]

Other medication

- NSAIDs: Anti-inflammatory. They are commonly used in conjunction with other therapy. For more severe cases narcotic prescription drugs may be used. NSAID injections can be helpful for severe pain or if stomach pain prevents oral NSAID use.

- MST: Morphine sulphate tablets and other opioid painkillers work by mimicking the action of naturally occurring pain-reducing chemicals called "endorphins". There are different long acting and short acting medications that can be used alone or in combination to provide appropriate pain control.

- Diclofenac in suppository or pill form. Taken to reduce inflammation and as an analgesic reducing pain.

- Following laparoscopic surgery women who were given Chinese herbs were reported to have comparable benefits to women with conventional drug treatments, though the journal article that reviewed this study also noted that "the two trials included in this review are of poor methodological quality so these findings must be interpreted cautiously. Better quality randomised controlled trials are needed to investigate a possible role for CHM [Chinese Herbal Medicine] in the treatment of endometriosis.",[45]

- Pentoxifylline, an immuno-modulatory agent

Surgery

Procedures are classified as

- conservative when reproductive organs are retained,

- semi-conservative when ovarian function is allowed to continue,

Conservative therapy consists of the excision (called cystectomy) of the endometrium, adhesions, resection of endometriomas, and restoration of normal pelvic anatomy as much as is possible.[6] There are combinations as well, notably one consisting of cystectomy followed by ablative surgery (removal of endometrium) using a CO2 laser to vaporize the remaining 10%–20% of the endometrioma wall close to the hilus.[46] Laparoscopy, besides being used for diagnosis, can also be an option for surgery. It's considered a "minimally invasive" surgery because the surgeon makes very small openings (incisions) at (or around) the belly button and lower portion of the belly. A thin telescope-like instrument (the laparoscope) is placed into one incision, which allows the doctor to look for endometriosis using a small camera attached to the laparoscope. Small instruments are inserted through the incisions to remove the tissue and adhesions. Because the incisions are very small, there will only be small scars on the skin after the procedure. The patient usually can go home the day of the surgery and should be able to return to their usual activities.[47]

Semi-conservative therapy preserves a healthy appearing ovary, but also increases the risk of recurrence.[48]

For patients with extreme pain, a presacral neurectomy may be indicated where the nerves to the uterus are cut. However, strong clinical evidence showed that presacral neurectomy is more effective in pain relief if the pelvic pain is midline concentrated, and not as effective if the pain extends to the left and right lower quadrants of the abdomen.[6] This is because the nerves to be transected in the procedure are innervating the central or the midline region in the female pelvis. Furthermore, women who had presacral neurectomy have higher prevalence of chronic constipation not responding well to medication treatment because of the potential injury to the parasympathetic nerve in the vicinity during the procedure.

After surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement, a review study estimated the overall endometriosis recurrence rate to be approximately 10% (ranging between 5–25%).[49]

Comparison of medicinal and surgical interventions

Efficacy studies show that both medicinal and surgical interventions produce roughly equivalent pain-relief benefits. Recurrence of pain was found to be 44 and 53 percent with medicinal and surgical interventions, respectively.[13] However, each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages.[1]

Advantages of medicinal interventions

- Decrease initial cost

- Empirical therapy (i.e. can be easily modified as needed)

- Effective for pain control

Disadvantages of medicinal interventions

- Adverse effects are common

- Not likely to improve fertility

- Some can only be used for limited periods of time

Advantages of surgery

- Has significant efficacy for pain control.[50]

- Has increased efficacy over medicinal intervention for infertility treatment

- Combined with biopsy, it is the only way to achieve a definitive diagnosis

- Can often be carried out as a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure to reduce morbidity and minimize the risk of post-operative adhesions[51]

Treatment of infertility

While roughly similar to medicinal interventions in treating pain, the efficacy of surgery is especially significant in treating infertility. One study has shown that surgical treatment of endometriosis approximately doubles the fecundity (pregnancy rate).[52] The use of medical suppression after surgery for minimal/mild endometriosis has not shown benefits for patients with infertility.[7] Use of fertility medication that stimulates ovulation (clomiphene citrate, gonadotropins) combined with intrauterine insemination (IUI) enhances fertility in these patients.[7]

In-vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures are effective in improving fertility in many women with endometriosis. IVF makes it possible to combine sperm and eggs in a laboratory and then place the resulting embryos into the woman's uterus. The decision when to apply IVF in endometriosis-associated infertility takes into account the age of the patient, the severity of the endometriosis, the presence of other infertility factors, and the results and duration of past treatments.

Other treatments

- One theory above suggests that endometriosis is an auto-immune condition and if the immune system is compromised with a food intolerance, then removing that food from the diet can, in some people, have an effect. Various dietary recommendations are made in popular media. For example, common intolerances in people with endometriosis are claimed to be wheat, sugar, meat and dairy.[53] Avoiding foods high in hormones and inflammatory fats also appears to be important in endometriosis pain management.[citation needed] Eating foods high in indole-3-carbinol, such as cruciferous vegetables appears to be helpful in balancing hormones and managing pain.[54] However, these popular claims are typically not supported by scientific studies. According to one scientific study, diets high in fat and low in fruit and β-carotene were associated with a lower risk of endometriosis,[55] contradicting the typical idea of a healthy diet. Consumption of omega 3 fatty acids, particularly EPA, as a food supplement has been suggested as a therapy for endometriosis.[56] The use of soy has been reported to both alleviate pain and to aggravate symptoms, making its use questionable.[57]

- Physical therapy for pain management in endometriosis has been investigated in a pilot study suggesting possible benefit.[58] Physical exertion such as lifting, prolonged standing or running does exacerbate pelvic pain. Use of heating pads on the lower back area, may provide some temporary relief.

- Laboratory studies indicate that heparin may alleviate endometriosis-associated fibrosis.[59]

Prognosis

Proper counseling of patients with endometriosis requires attention to several aspects of the disorder. Of primary importance is the initial operative staging of the disease to obtain adequate information on which to base future decisions about therapy. The patient's symptoms and desire for childbearing dictate appropriate therapy. Not all therapy works for all patients. Some patients have recurrences after surgery or pseudo-menopause. In most cases, treatment will give patients significant relief from pelvic pain and assist them in achieving pregnancy.[60] It is important for patients to be continually in contact with their physician and keep an open dialog throughout treatment. This is a disease without a cure but with the proper communication, a woman with endometriosis can attempt to live a normal, functioning life. Using cystectomy and ablative surgery, pregnancy rates are approximately 40%.[46]

Recurrence

The underlying process that causes endometriosis may not cease after surgical or medical intervention. The most recent studies have shown that endometriosis recurs at a rate of 20 to 40 percent within five years following conservative surgery,[61] unless hysterectomy is performed or menopause reached. Monitoring of patients consists of periodic clinical examinations and sonography. Also, the CA 125 serum antigen levels have been used to follow patients with endometriosis. With combined cystectomy and ablative surgery, one study showed recurrence of a small endometrioma in only one case among fifty-two women (2%) at a mean follow-up of 8.3 months.[46]

Vaginal childbirth decreases recurrence of endometriosis. In contrast, endometriosis recurrence rates have been shown to be higher in women who have not given birth vaginally, such as in Cesarean section.[62]

Epidemiology

Endometriosis can affect any female, from premenarche to postmenopause, regardless of race or ethnicity or whether or not they have had children. It is primarily a disease of the reproductive years. Estimates about its prevalence vary, but 5–10% is a reasonable number, more common in women with infertility (20–50%) and women with chronic pelvic pain (about 80%).[13] As an estrogen-dependent process, it can persist beyond menopause and persists in up to 40% of patients following hysterectomy.[63] In some cases, it may also begin beyond menopause and it has also been described in men taking high-dose estrogen therapy.[64][65]

Other associated conditions

There are some additional conditions that are seen in increased frequency among people with endometriosis, but where there is uncertainty whether these are factors that predispose to endometriosis or vice versa.

Endometriosis bears no relationship to endometrial cancer. Current research has demonstrated an association between endometriosis and certain types of cancers, notably ovarian cancer, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and brain cancer.[66][67][68] Endometriosis often also coexists with leiomyoma or adenomyosis, as well as autoimmune disorders. A 1988 survey conducted in the US found significantly more Hypothyroidism, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, autoimmune diseases, allergies and asthma in women with endometriosis compared to the general population.[69]

Prevention

Use of combined oral contraceptives is associated with a reduced risk of endometriosis, apparently giving a relative risk of endometriosis of 0.63 during active use, yet with limited quality of evidence according to a systematic review.[70]

People living with endometriosis

- Padma Lakshmi cookbook author, actress, model and television host [71]

- Emma Bunton singer [72]

- Nikki Cascone chef and restaurant owner [73]

- Annabel Croft tennis player, radio presenter and television presenter [74]

- Karen Duffy model, television personality and actress [75]

- Anna Friel actress [76]

- Julianne Hough professional ballroom dancer, country music singer and actress [77]

- Jillian Michaels (personal trainer) celebrity personal trainer, reality show personality, direct-response television pitchwoman and entrepreneur [78]

- Marilyn Monroe actress [79]

- Tia Mowry actress [80]

- Elizabeth Oas actress [81]

- Dolly Parton singer-songwriter, author, multi-instrumentalist, actress and philanthropist [82]

- Queen Victoria monarch [83]

- Louise Redknapp singer [84]

- Susan Sarandon actress and social activist [85]

- Lacey Schwimmer ballroom dancer and singer [86]

- Stephanie St. James actress [87]

- Kirsten Storms actress [88]

- Anthea Turner television presenter and media personality [89]

References

- ^ a b c "Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis". American Academy of Family Physicians. 1999-10-15. http://www.aafp.org/afp/991015ap/1753.html. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ Perloe, Mark. "Miracle Babies: Chapter 17 Endometriosis: Conquering the Silent Invader". http://www.ivf.com/ch17mb.html.

- ^ a b Stratton, P.; Berkley, K. J. (2010). "Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: Translational evidence of the relationship and implications". Human Reproduction Update 17 (3): 327–346. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq050. PMID 21106492.

- ^ Endometriosis;NIH Pub. No. 02-2413; September 2002

- ^ a b c d Ballard, K.; Lane, H.; Hudelist, G.; Banerjee, S.; Wright, J. (2010). "Can specific pain symptoms help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? A cohort study of women with chronic pelvic pain". Fertility and Sterility 94 (1): 20. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.164. PMID 19342028.

- ^ a b c Speroff L, Glass RH, Kase NG (1999). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility (6th ed.). Lippincott Willimas Wilkins. p. 1057. ISBN 0-683-30379-1.

- ^ a b c Buyalos RP, Agarwal SK (October 2000). "Endometriosis-associated infertility". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology 12 (5): 377–81. doi:10.1097/00001703-200010000-00006. ISSN 1040-872X. PMID 11111879. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=1040-872X&volume=12&issue=5&spage=377.

- ^ Women with Endometriosis Have Higher Rates of Some Diseases; NIH News Release; 26 September 2002; http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/sep2002/nichd-26.htm

- ^ Colette S & Donnez J (July 2011). "Are aromatase inhibitors effective in endometriosis treatment?". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 20 (7): 917–31.

- ^ Lone Hummelshoj. "Adhesions in Endometriosis". endometriosis.org. http://www.endometriosis.org/adhesions.html. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ^ a b c Ueda, Y.; Enomoto, T.; Miyatake, T.; Fujita, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Kanagawa, T.; Shimizu, H.; Kimura, T. (2010). "A retrospective analysis of ovarian endometriosis during pregnancy". Fertility and Sterility 94 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.092. PMID 19356751.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fauser, B. C. J. M.; Diedrich, K.; Bouchard, P.; Dominguez, F.; Matzuk, M.; Franks, S.; Hamamah, S.; Simon, C. et al. (2011). "Contemporary genetic technologies and female reproduction". Human Reproduction Update 17 (6): 829–847. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr033. PMC 3191938. PMID 21896560. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3191938.

- ^ a b c Dharmesh Kapoor and Willy Davila, 'Endometriosis', eMedicine (2005).

- ^ Kashima K, Ishimaru T, Okamura H, et al. (January 2004). "Familial risk among Japanese patients with endometriosis". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 84 (1): 61–4. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00340-0. ISSN 0020-7292. PMID 14698831.

- ^ Treloar SA, Wicks J, Nyholt DR, et al. (September 2005). "Genomewide linkage study in 1,176 affected sister pair families identifies a significant susceptibility locus for endometriosis on chromosome 10q26". American Journal of Human Genetics 77 (3): 365–76. doi:10.1086/432960. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1226203. PMID 16080113. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1226203.

- ^ Painter JN et al. (2010). "Genome-wide association study identifies a locus at 7p15.2 associated with endometriosis". Nature Genetics 43 (1): 51–54. doi:10.1038/ng.731. ISSN 1061-4036. PMC 3019124. PMID 21151130. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3019124.

- ^ "Evidence Indicates Endometriosis Could be Linked to Environment". ksl.com. 2007-11-26. http://www.ksl.com/?nid=148&sid=2223164. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ "Toxic Link to Endo". Endometriosis Association. 2010-04-22. http://www.endometriosisassn.org/environment.html. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- ^ Daniel W. Cramer, Emery Wilson, Robert J. Stillman, Merle J. Berger, Serge Belisle, Isaac Schiff, Bruce Albrecht, Mark Gibson, Bruce V. Stadel, Stephen C. Schoenbaum (1986). "The Relation of Endometriosis to Menstrual Characteristics, Smoking, and Exercise". JAMA1986;255(14):1904-1908 255 (14): 1904–8. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03370140102032. PMID 3951117. http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/255/14/1904.abstract.

- ^ Bulun SE, Zeitoun K, Sasano H, Simpson ER (1999). "Aromatase in aging women". Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology 17 (4): 349–58. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1016244. ISSN 0734-8630. PMID 10851574.

- ^ Batt RE, Mitwally MF (December 2003). "Endometriosis from thelarche to midteens: pathogenesis and prognosis, prevention and pedagogy". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 16 (6): 337–47. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2003.09.008. ISSN 1083-3188. PMID 14642954.

- ^ Marsh EE, Laufer MR (March 2005). "Endometriosis in premenarcheal girls who do not have an associated obstructive anomaly". Fertility and Sterility 83 (3): 758–60. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.025. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 15749511.

- ^ Griffith JS, Liu YG, Tekmal RR, Binkley PA, Holden AE, Schenken RS (April 2010). "Menstrual endometrial cells from women with endometriosis demonstrate increased adherence to peritoneal cells and increased expression of CD44 splice variants". Fertil. Steril. 93 (6): 1745–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.012. PMC 2864724. PMID 19200980. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2864724.

- ^ Juhasz-Böss, I.; Hofele, A.; Lattrich, C.; Buchholz, S.; Ortmann, O.; Malik, E. (2010). "Matrix metalloproteinase messenger RNA expression in human endometriosis grafts cultured on a chicken chorioallantoic membrane". Fertility and Sterility 94 (1): 40–45. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.052. PMID 19345347.

- ^ Bourlev, V.; Iljasova, N.; Adamyan, L.; Larsson, A.; Olovsson, M. (2010). "Signs of reduced angiogenic activity after surgical removal of deeply infiltrating endometriosis". Fertility and sterility 94 (1): 52–57. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.019. PMID 19324337.

- ^ Ouyang, Z.; Osuga, Y.; Hirota, Y.; Hirata, T.; Yoshino, O.; Koga, K.; Yano, T.; Taketani, Y. (2010). "Interleukin-4 induces expression of eotaxin in endometriotic stromal cells". Fertility and Sterility 94 (1): 58–62. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.129. PMID 19338989.

- ^ Sharma, I.; Dhaliwal, L.; Saha, S.; Sangwan, S.; Dhawan, V. (2010). "Role of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2alpha and 25-hydroxycholesterol in the pathophysiology of endometriosis". Fertility and sterility 94 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.141. PMID 19324352.

- ^ Gleicher N, el-Roeiy A, Confino E, Friberg J (July 1987). Is endometriosis an autoimmune disease?. 70. pp. 115–22. PMID 3110710. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3110710.

- ^ Capellino S, Montagna P, Villaggio B, et al. (June 2006). "Role of estrogens in inflammatory response: expression of estrogen receptors in peritoneal fluid macrophages from endometriosis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1069: 263–7. doi:10.1196/annals.1351.024. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 16855153.

- ^ Redwine DB (October 2002). "Was Sampson wrong?". Fertility and Sterility 78 (4): 686–93. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03329-0. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 12372441.

- ^ Signorile PG, Baldi F, Bussani R, D'Armiento M, De Falco M, Baldi A (April 2009). "Ectopic endometrium in human foetuses is a common event and sustains the theory of müllerianosis in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, a disease that predisposes to cancer" (Free full text). Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 28: 49. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-28-49. ISSN 0392-9078. PMC 2671494. PMID 19358700. http://www.jeccr.com/content/28//49.

- ^ Matsuura K, Ohtake H, Katabuchi H, Okamura H (1999). "Coelomic metaplasia theory of endometriosis: evidence from in vivo studies and an in vitro experimental model". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 47 Suppl 1: 18–20; discussion 20–2. doi:10.1159/000052855. ISSN 0378-7346. PMID 10087424.

- ^ Laschke, M. W.; Giebels, C.; Menger, M. D. (2011). "Vasculogenesis: A new piece of the endometriosis puzzle". Human Reproduction Update 17 (5): 628–636. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr023. PMID 21586449.

- ^ Shawn Daly, MD, Consulting Staff, Catalina Radiology, Tucson, Arizona (October 18 2004). "Endometrioma/Endometriosis". WebMD. http://www.emedicine.com/radio/topic250.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ Nisolle M, Paindaveine B, Bourdon A, Berlière M, Casanas-Roux F, Donnez J (June 1990). "Histologic study of peritoneal endometriosis in infertile women". Fertility and Sterility 53 (6): 984–8. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 2351237.

- ^ Warren Volker, OB/GYN MD Endometriosis Diagnosis and Cure

- ^ Brody, Jane E. "In women, hernias may be hidden agony" The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. 18 May 2011.

- ^ American Society For Reproductive M, (May 1997). "Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996". Fertility and Sterility 67 (5): 817–21. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81391-X. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 9130884.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i May, K. E.; Conduit-Hulbert, S. A.; Villar, J.; Kirtley, S.; Kennedy, S. H.; Becker, C. M. (2010). "Peripheral biomarkers of endometriosis: A systematic review". Human Reproduction Update 16 (6): 651–674. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq009. PMC 2953938. PMID 20462942. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2953938.

- ^ May, K. E.; Villar, J.; Kirtley, S.; Kennedy, S. H.; Becker, C. M. (2011). "Endometrial alterations in endometriosis: A systematic review of putative biomarkers". Human Reproduction Update 17 (5): 637–653. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr013. PMID 21672902.

- ^ Endometriosis[dead link]

- ^ Harada T, Momoeda M, Taketani Y, Hoshiai H, Terakawa N (November 2008). "Low-dose oral contraceptive pill for dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial". Fertility and Sterility 90 (5): 1583–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.051. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 18164001.

- ^ How Lupron Depot therapy is used in treating Endometriosis[dead link]

- ^ Attar E, Bulun SE (May 2006). "Aromatase inhibitors: the next generation of therapeutics for endometriosis?". Fertility and Sterility 85 (5): 1307–18. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.064. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 16647373.

- ^ Flower A, Liu JP, Chen S, Lewith G, Little P (2009). Flower, Andrew. ed. "Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006568. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006568.pub2. PMID 19588398.

- ^ a b c Donnez, J.; Lousse, J. C.; Jadoul, P.; Donnez, O.; Squifflet, J. (2010). "Laparoscopic management of endometriomas using a combined technique of excisional (cystectomy) and ablative surgery". Fertility and Sterility 94 (1): 28–32. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.065. PMID 19361793.

- ^ "Endometriosis and Infertility: Can Surgery Help?". American Society for Reproductive Medicine. 2008. http://www.asrm.org/uploadedFiles/ASRM_Content/Resources/Patient_Resources/Fact_Sheets_and_Info_Booklets/endometriosis_infertility.pdf. Retrieved 31 Oct. 2010.

- ^ Namnoum AB, Hickman TN, Goodman SB, Gehlbach DL, Rock JA (November 1995). "Incidence of symptom recurrence after hysterectomy for endometriosis". Fertility and Sterility 64 (5): 898–902. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 7589631.

- ^ Meuleman, C.; Tomassetti, C.; D'hoore, A.; Van Cleynenbreugel, B.; Penninckx, F.; Vergote, I.; D'hooghe, T. (2011). "Surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement". Human Reproduction Update 17 (3): 311–326. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq057. PMID 21233128.

- ^ Kaiser A, Kopf A, Gericke C, Bartley J, Mechsner S. (16 January 2009). "The influence of peritoneal endometriotic lesions on the generation of endometriosis-related pain and pain reduction after surgical excision". Arch Gynecol Obstet. 280 (3): 369–73. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0921-z. ISSN 0932-0067. PMID 19148660.

- ^ Coagulation versus excision of primary superficial endometriosis: a 2-year follow-up. Radosa MP, Bernardi TS, Georgiev I, Diebolder H, Camara O, Runnebaum IB. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010 Jun;150(2):195-8.

- ^ Marcoux S, Maheux R, Bérubé S (July 1997). "Laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis". The New England Journal of Medicine 337 (4): 217–22. doi:10.1056/NEJM199707243370401. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 9227926.

- ^ Dian Shepperson Mills and Michael Vernon. "Endometriosis a key to healing and fertility through nutrition". endometriosis.co.uk. http://www.endometriosis.co.uk.

- ^ "Pain, Infertility, Hormone Problems? :: Health and Disease :: Women's Health Issues :: endometriosis". Alive.com. http://www.alive.com/1967a5a2.php?subject_bread_cramb=429. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ Trabert B, Peters U, De Roos AJ, Scholes D, Holt VL, Br J Nutr. 2011 Feb;105(3):459-67. Diet and risk of endometriosis in a population-based case-control study.PubMed

- ^ Netsu S, Konno R, Odagiri K, Soma M, Fujiwara H, Suzuki M (October 2008). "Oral eicosapentaenoic acid supplementation as possible therapy for endometriosis". Fertility and Sterility 90 (4 Suppl): 1496–502. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.014. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 18054352.

- ^ Chandrareddy A, Muneyyirci-Delale O, McFarlane SI, Murad OM (May 2008). "Adverse effects of phytoestrogens on reproductive health: a report of three cases". Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 14 (2): 132–5. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2008.01.002. ISSN 1744-3881. PMID 18396257.

- ^ Wurn, L; Wurn, B; Kingiii, C; Roscow, A; Scharf, E; Shuster, J (2006). "P-343Treating endometriosis pain with a manual pelvic physical therapy". Fertility and Sterility 86 (3): S262. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.699.

- ^ Nasu, K.; Tsuno, A.; Hirao, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Yuge, A.; Narahara, H. (2010). "Heparin is a promising agent for the treatment of endometriosis-associated fibrosis". Fertility and Sterility 94 (1): 46–51. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.057. PMID 19338998.

- ^ Sanaz Memarzadeh, MD, Kenneth N. Muse, Jr., MD, & Michael D. Fox, MD (September 21 2006). "Endometriosis". Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of endometriosis.. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. http://www.health.am/gyneco/endometriosis/. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "Recurrent Endometriosis: Surgical Management". Endometriosis. The Cleveland Clinic. 7. http://my.clevelandclinic.org/disorders/Endometriosis/hic_Recurrent_Endometriosis_Surgical_Management.aspx. Retrieved 31 Oct. 2010.

- ^ Bulletti C, Montini A, Setti PL, Palagiano A, Ubaldi F, Borini A (June 2009). "Vaginal parturition decreases recurrence of endometriosis". Fertil. Steril. 94 (3): 850–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.012. PMID 19524893.

- ^ "Endometriosis – Hysterectomy". Umm.edu. http://www.umm.edu/patiented/articles/what_radical_surgery_hysterectomy_endometriosis_000074_11.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ "Endometriosis FAQ". Bioscience.org. http://www.bioscience.org/books/endomet/end34-65.htm#34. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ^ . PMID 4014886.

- ^ "Endometriosis cancer risk". medicalnewstoday.com. 5 July 2003. http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=3890. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ^ Roberts, Michelle (3 July 2007). "Endometriosis 'ups cancer risk'". BBC News (BBC / news.bbc.co.uk). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6262140.stm. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ^ Audebert A (April 2005). "La femme endométriosique est-elle différente ? [Women with endometriosis: are they different from others?]" (in French). Gynécologie, Obstétrique & Fertilité 33 (4): 239–46. doi:10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.010. ISSN 1297-9589. PMID 15894210.

- ^ Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P (October 2002). "High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis" (Free full text). Human Reproduction 17 (10): 2715–24. doi:10.1093/humrep/17.10.2715. ISSN 0268-1161. PMID 12351553. http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12351553.

- ^ Vercellini, P.; Eskenazi, B.; Consonni, D.; Somigliana, E.; Parazzini, F.; Abbiati, A.; Fedele, L. (2010). "Oral contraceptives and risk of endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update 17 (2): 159–170. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq042. PMID 20833638.

- ^ http://www.endofound.org/padma-lakshmi

- ^ http://www.ok.co.uk/posts/view/19557/End-of-pain-Coping-with-endometriosis

- ^ http://celebritybabyscoop.com/2010/11/10/nikki-cascone

- ^ http://www.fastbleep.com/medical-notes/o-g-and-paeds/17/38/253

- ^ http://www.drdonnica.com/celebrities/00004929.htm

- ^ http://www.redorbit.com/news/health/128565/body_talk_celebrity_baby_clinic

- ^ http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/27407271

- ^ http://www.jillianmichaels.com

- ^ http://www.fertilethoughts.com/forums/endometriosis/704004-other-famous-people-endo.html

- ^ http://chancesour.blogspot.com/2011/03/what-me-jillian-michaels-padma-lakshmi.html

- ^ http://ustrendstoday.info/endometriosis-8-celebrities-who-have-been-very-open-with-their-strugglephotos.html

- ^ http://community.wegohealth.com/profiles/blogs/famous-people-affected-by

- ^ http://www.fertilethoughts.com/forums/endometriosis/704004-other-famous-people-endo.html

- ^ http://www.redorbit.com/news/health/128565/body_talk_celebrity_baby_clinic

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IetE1BOjEYs

- ^ http://www.shape.com/celebrities/endometriosis-scare-julianne-hough-lacey-schwimmer

- ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zEu0mNGE19g

- ^ http://wubtub.blogspot.com/2011/10/kirsten-storms-battles-endometriosis.html

- ^ http://community.wegohealth.com/profiles/blogs/famous-people-affected-by

External links

Female diseases of the pelvis and genitals (N70–N99, 614–629) Internal AdnexaOophoritis · Ovarian cyst (Follicular cyst of ovary, Corpus luteum cyst, Theca lutein cyst) · Endometriosis of ovary · Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome · Ovarian torsion · Ovarian apoplexy · Mittelschmerz · Female infertility (Anovulation, Poor ovarian reserve)Endometritis · Endometriosis · Endometrial polyp · Endometrial hyperplasia · Asherman's syndrome · Dysfunctional uterine bleedingCervicitis · Cervical polyp · Nabothian cyst · Cervical incompetence · Female infertility (Cervical stenosis) · Cervical dysplasiaGeneralVaginitis (Bacterial vaginosis, Atrophic vaginitis, Candidal vulvovaginitis) · Leukorrhea/Vaginal discharge · Hematocolpos/HydrocolposOther/generalPelvic inflammatory disease · Pelvic congestion syndromeExternal Categories:- Noninflammatory disorders of female genital tract

- Menstrual cycle

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.