- Hirsau Abbey

-

Hirsau Abbey, formerly known as Hirschau Abbey, was once one of the most prominent Benedictine abbeys of Germany. It was located in the town of Hirsau, in the Diocese of Speyer, near Calw in the present Baden-Württemberg.

Contents

History

The monastery was founded in about 830 by Count Erlafried of Calw at the instigation of his son, Bishop Notting of Vercelli, who gave it the body of Saint Aurelius, an Armenian bishop, brought from Italy among other treasures; they were first placed in the oratory of Saint Nazarius at Calw, while the monastery at Hirschau was being built. It was settled by a colony of fifteen monks from Fulda Abbey, disciples of Rabanus Maurus and Walafrid Strabo, under the abbot Liudebert or Lutpert. Count Erlafried endowed the new foundation with lands and other gifts, and made a solemn donation of the whole into the hands of Lutpert, on condition that the Rule of St. Benedict should be observed. The abbey church, dedicated to Saint Peter, was not completed until 838, in which year it was consecrated by Othgar, Archbishop of Mainz, who at the same time translated the body of Saint Aurelius from its temporary resting-place to the new church. Abbot Lutpert died in 853, having brought about a substantial increase both in the possessions of the abbey and in the number of the monks under his rule. Regular observance flourished under him and his successors and a successful monastic school was established.

Over about a hundred and fifty years, under the care of the Counts of Calw, it enjoyed great prosperity, and became an important seat of learning.

However, towards the end of the 10th century the ravages of pestilence, combined with the greed of its patrons and the laxity of the community, brought it to ruin. In 988 a severe plague devastated the neighbourhood and carried off sixty of the monks including the abbot, Hartfried. Only a dozen were left to elect a successor, and they divided into two parties. The more fervent chose one Conrad, whose election was confirmed by the Bishop of Speyer, but some of the others, who favoured a more relaxed rule, elected an opposition abbot in the person of Eberhard, the cellarer. For some time the dispute ran high between the rival superiors and their respective followers. The Count of Calw supported the claims of Eberhard, but neither party would give way to the other and in the end the count brought in an armed force to settle the quarrel. The result was that the abbey was pillaged, the monks dispersed, and the valuable library destroyed. The count became master of the property and the abbey remained empty for over sixty years, during which time the buildings fell into a ruinous state.

In 1049 Leo IX, uncle of Count Adalbert, and grandson of the spoliator, came to Calw, and required Adalbert to restore the abbey. This he did, but so slowly that it was not ready for occupation until 1065, when it was settled by a dozen monks from the celebrated Swiss Einsiedeln Abbey, with Abbot Frederick at their head.

It was however his successor who revived and even surpassed the former renown and prosperity of the abbey. This was the famous William of Hirsau, abbot from 1069 to 1091, a monk of St. Emmeram's Abbey, Regensburg, appointed abbot in 1069. When he came the condition of the monastery was far from satisfactory. The buildings were still incomplete, Count Adalbert still retained possession of some of the monastic property, together with a certain amount of unhelpful influence over the community, and regular discipline was very much relaxed. Abbot William's zeal and prudence by degrees remedied this unsatisfactory state of affairs and inaugurated a period of great prosperity, both spiritual and temporal. He secured the independence of the abbey from the Count of Calw and placed its finances on a sound footing; he completed the buildings already begun and afterwards greatly added to them, as the needs of the increasing community required; and he refounded the monastic school for which the abbey had formerly been famous throughout Germany.

But his greatest work, perhaps, and that for which his name is best remembered, was the reformation that he effected within the community itself. Cluny was then at the height of its fame and William sent some of his monks there to learn the Cluniac customs and rule, after which the Cluniac discipline was introduced at Hirsau. By his Constitutiones Hirsaugienses, a new religious order, the Ordo Hirsaugiensis, was formed. Known as the Hirsau Reforms, the adoption of this rule revitalised Benedictine monasteries throughout Germany, such as those of Blaubeuren, Erfurt and Schaffhausen.

The friend and correspondent of Pope Gregory VII, and of Anselm of Canterbury, William took active part in the politico-ecclesiastical controversies of his time, principally the Investiture Controversy. He was also author of inter alia the treatise De musica et tonis, as well as the Philosophicarum et astronomicarism institutionuin libri iii.

The abbot then wrote his well-known "Consuetudines Hirsaugienses"[1] which for several centuries remained the standard of monastic observance. Under William monks were sent out from Hirsau to reform other German monasteries on the same lines, and from it seven new monasteries were founded. The numbers of the community increased to 150 under his rule, manual labour and the copying of manuscripts forming an important part of their occupations. Numerous exemptions and other privileges were obtained from time to time from emperors and popes.

About the end of the 12th century Hirsau Abbey was again very perceptibly on the decline both materially and morally. It never afterwards again rose into importance.

In the twelfth century the autocratic rule of Abbot Manegold caused for a time some internal dissensions and a consequent decline of strict discipline, but the vigorous efforts of several abbots checked the decadence, and temporarily re-established the stricter observance.

In the fifteenth century, however, the famous "Customs" gradually became little more than a dead letter. Wolfram, the thirty-eighth abbot (1428-1460), introduced the contemporary Melk Reform. A few years later Hirsau adopted the Constitutions of Bursfelde Abbey and became part of the Bursfelde Congregation. Wolfram's successor, Bernhard, carried on the work of revival, freed the abbey from its debts, restored the monastic buildings, and also reformed several other monasteries.

In the days of Abbot John III (1514-56) Hirsau fell on hard times: the Protestant Reformation began to make its influence felt, and after a brief period of struggle, the abbey, through the involvement of Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg, passed into Lutheran hands, though still maintaining its monastic character. In consequence of the Reformation it was secularized in 1558. In 1630 it became Catholic again for a short time, but after the Peace of Westphalia (1648) it once more came under the control of the Dukes of Württemberg and another series of Lutheran abbots presided over it.

The community eventually came to an end and the once famous Hirsau Abbey was finally destroyed by the French under Melac in 1692. Only a few ruins now remain to mark its site.

Galleries

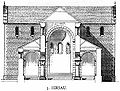

- Church of St. Aurelius

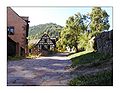

- Monastery

Notes

- ^ P. L., CL, and Herrgott, "Vetus Disciplina Monastica",

Sources and references

- Herrbach-Schmidt, B., Westermann, C.: Klostermuseum Hirsau: Führer durch des Zweigmuseum des Badischen Landesmuseums. Badisches Landesmuseum, Karlsruhe(1998), ISBN 3-923132-69-7

- Teschauer, O.: Kloster Hirsau, Ein Kurzführer, Calwer Druckzentrum,(1991), ISBN 3-926802-10-3

- Würfel, M.: Lernort, Kloster Hirsau. Einhorn-Verlag, Eduard Dietenberger GmbH (1998), ISBN 3-927654-65-5

- "Abbey of Hirschau". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07363a.htm.

- The Chronicon Hirsaugiense, or, as it is called in the later edition, Annales Hirsaugienses of Abbot Trithemius by Trithemius, the celebrated Abbot of Spanheim, who had access to its archives before they were dispersed (Basel, 1559; St Gall, 1690), although containing much that is merely legendary, is nevertheless an important source of information up to the year 1503, not only on the affairs of this monastery, but also on the early history of Germany.

- The Codex Hirsaugiensis was edited by A. F. Gfrorer and printed at Stuttgart in 1843.

- Baer, 1897. Die Hirsauer Bauschule. Freiburg.

- Giseke, 1883. Die Hirschauer während des Investiturstreits. Gotha.

- Helmsdorfer, 1874. Forschungen zur Geschichte des Abts Wilhelm von Hirschau. Göttingen

- Besides the "Customs" already referred to, William of Hirschau left a treatise "De Musica et Tonis" (printed by Gerbert, "Script. Eccles.", and also by Migne, P. L., CL).

- Klaiber, C.H., 1886. Das Kloster Hirschau. Tübingen.

- Steck, 1844. Das Kloster Hirschau

- Süssmann, 1903. Forschungen zur Geschichte des Klosters Hirschau. Halle.

- Weizsäcker, 1898. Führer durch die Geschichte des Klosters Hirschau. Stuttgart

External links

- (German) Hirsau im Nagoldtal

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.Coordinates: 48°44′16″N 8°43′56″E / 48.73778°N 8.73222°E

- "Hunting Lodge (Jagdschloss) in 3D Warehouse".[1]

- "The Hunting Lodge (Jagdschloss) in Wikimapia". [2]

- "The Lady Chapel in 3D Warehouse".[3]

- "The Cloister in 3D Warehouse".[4]

Categories:- Benedictine monasteries in Germany

- Monasteries in Baden-Württemberg

- Christian monasteries established in the 9th century

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.