- Caesura

-

For Helios album, see Caesura (album).

In meter, a caesura (alternative spellings are cæsura and cesura) is a complete pause in a line of poetry or in a musical composition. The plural form of caesura is caesuras or caesurae. Caesurae feature prominently in Greek and Latin verse, especially in the heroic verse form, dactylic hexameter.

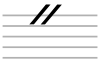

In poetry, a masculine caesura follows a stressed syllable while a feminine caesura follows an unstressed syllable. A caesura is also described by its position in a line of poetry. A caesura close to the beginning of a line is called an initial caesura, one in the middle of a line is medial, and one near the end of a line is terminal. Initial and terminal caesurae were rare in formal, Romance, and Neoclassical verse, which preferred medial caesurae. In scansion, poetry written with signs to indicate the length and stress of syllables, the "double pipe" sign ("||") is used to denote the position of a caesura.

In musical notation, caesura denotes a brief, silent pause, during which metrical time is not counted.

In musical notation, the symbol for a caesura is a pair of parallel lines set at an angle, rather like a pair of forward slashes: //. The symbol is popularly called "tram-lines" in the U.K. and "railroad tracks" in the U.S.

Contents

Examples

In the following examples, the symbol for the caesura in scanning poetry, the "double pipes" ("||"), are inserted into the text of the poem to indicate the position of the audible pause.

Homer

Caesurae were widely used in Greek poetry, for example in the opening line of the Iliad:

- μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ || Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος

- ("Sing, o goddess, the rage || of Achilles, the son of Peleus.")

This line includes a masculine caesura after θεὰ, a natural break that separates the line into two logical parts. Unlike later writers, Homeric lines more commonly employ feminine caesurae.

Latin

Caesurae were widely used in Latin poetry, for example in the opening line of Virgil's Aeneid:

- Arma virumque cano || Troiae qui primus ab oris

- (Of arms and the man, I sing. || Who first from the shores of Troy...)

This line uses caesura in the medial position. In dactylic hexameter, a caesura occurs any time the ending of a word does not coincide with the beginning or the end of a metrical foot; in modern prosody, however, it is only called one when the ending also coincides with an audible pause in the line.

The ancient elegiac couplet form of the Greeks and Romans contained a line of dactylic hexameter followed by a line of pentameter. The pentameter often displayed a clearer caesura, as in this example from Propertius:

- Cynthia prima fuit; || Cynthia finis erit.

- (Cynthia was the first; Cynthia will be the last)

Old English

The caesura was even more important to Old English verse than it was to Latin or Greek poetry. In Latin or Greek poetry, the caesura could be suppressed for effect in any line. In the alliterative verse that is shared by most of the oldest Germanic languages, the caesura is an ever-present and necessary part of the verse form itself. The opening line of Beowulf reads:

- Hwæt! We Gardena || in gear-dagum,

- þeodcyninga, || þrym gefrunon,

- hu ða æþelingas || ellen fremedon.

- (So! The Spear-Danes in days gone by)

- (and the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness.)

- (We have heard of these princes' heroic campaigns.)

The basic form is accentual verse, with four stresses per line, separated by a caesura. Old English poetry added alliteration and other devices to this basic pattern.

Middle English

William Langland's Piers Ploughman:

- I loked on my left half || as þe lady me taughte

- And was war of a womman || worþeli ycloþed.

- (I looked on my left side / as the lady me taught)

- (and was aware of a woman / worthily clothed.)

Other examples

Caesurae can occur in later forms of verse, where they are usually optional. The so-called ballad meter, or the common meter of the hymn odists, is usually thought of as a line of iambic tetrameter followed by a line of trimeter, but it can also be considered a line of heptameter with a fixed caesura at the fourth foot.

Considering the break as a caesura in these verse forms, rather than a beginning of a new line, explains how sometimes multiple caesurae can be found in this verse form (from the ballad Tom o' Bedlam):

- From the hag and hungry goblin || that into rags would rend ye,

- And the spirits that stand || by the naked man || in the Book of Moons, defend ye!

In later and freer verse forms, the caesura is optional. It can, however, be used for rhetorical effect, as in Alexander Pope's line:

- To err is human; || to forgive, divine.

See also

- Haiku

- Meter (poetry)

- Old English poetry

- Saturnian (poetry)

References

- [1] “caesura” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 3 March 2007

Categories:- Poetic rhythm

- Musical notation

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.