- Occupation of the Jordan Valley (1918)

-

The British Empire's occupation of the Jordan Valley occurred during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I, beginning after the Capture of Jericho in February when the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment began patrolling an area near Jericho at the base of the road from Jerusalem. The occupation ended in September when the area was consolidated with other former Ottoman Empire territories which were won as a consequence of the British Empire victory at the Battle of Megiddo.

Despite the difficult climate and the unhealthy environment of the Jordan Valley, General Allenby decided that, in order to ensure the strength of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force's front line it was necessary to extend the line which stretched from the Mediterranean Sea, across the Judean Hills to the Dead Sea in order to protect his right flank. This line was held until September, providing a strong position from which to launch the attacks on Amman to the east and northwards to Damascus.

During the period from March to September the Ottoman Army held the hills of Moab on the eastern side of the valley and the northern section of valley. Their well placed artillery periodically shelled the occupying force and, particularly in May, German aircraft bombed and strafed bivouacs and horse lines.

Background

After the Capture of Jerusalem at the end of 1917 the Jordan River was crossed by infantry and mounted riflemen and bridgeheads established at the beginning of the unsuccessful first Transjordan attack on Amman in March. The defeat of the second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt and the withdrawal to the Jordan Valley on 3 to 5 May, marked the end of major operations until September 1918.[1]

Decision to occupy the valley

I am not strong enough to make holding attacks on both flanks, and the Turks can transfer their reserves from flank to flank as required. The Turks have more of these, the VII Army have 2400, and the VIII Army 5800 in Reserve. [see table] I must maintain my hold on the bridges of the Jordan, and my control of the Dead Sea. This will cause the Turks to keep a considerable force watching me, and ease pressure on Feisal and his forces. It is absolutely essential to me that he should continue to be active. He is a sensible, well–informed man; and he is fully alive to the limitations imposed on me. I keep in close touch with him, through Lawrence. I have now in the valley two Mounted Divisions and an Indian Infantry Brigade. I cannot lessen this number yet.

Allenby letter to Wilson 5 June 1918[2]Reasons for garrisoning the Jordan Valley include –

- The road from the Hedjaz railway station at Amman to Shunet Nimrin opposite the Ghoraniyeh crossing of the Jordan River, remained a serious strategic threat to the British right flank as a large German and Ottoman force could very quickly be moved from Amman to Shunet Nimrin and a major attack mounted into the valley.[3][Note 1]

- The plan for the advance in September required holding the Jordan bridgeheads and maintaining a continuous threat of another offensive across the Transjordan.[4]

- The mobility of the mounted force kept alive the possibility of a third Transjordan attack on this flank and their endurance of the terrible heat, may have confirmed the enemy's assumption, that the next advance would come in this sector of the front line.[5]

- The implied threat of a large mounted force which was constantly active in whatever part of the front line Desert Mounted Corps was based raised enemy expectations of a fresh attack being mounted in that area.[3]

- A withdrawal of Chauvel's force from the valley to the heights may have been contemplated but the lost territory would have to be re–taken before the proposed September operations.[3]

- Despite the huge numbers of sick projected to be suffered during the occupation of the Jordan Valley, the re-taking of the valley may have been more costly than holding it.[3]

- If a retreat out of the Jordan Valley took place, the alternative position in the wilderness overlooking the Jordan Valley was insufficient in either space or water to accommodate the Desert Mounted Corps.[3][6]

- A retreat out of the valley would enhance the already increased morale of the German and Ottoman forces and their standing in the region, following their Transjordan victories.[3]

- Normally mounted troops would be held in reserve, but Allenby did not think there were enough available infantry divisions to hold his front line while the radical reorganisation of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force was being carried out.[6]

It therefore was decided to defend the eastern flank from the Jordan valley with a strong garrison until September and to occupy a place many considered to be an unpleasant and unhealthy place and virtually uninhabitable during the hot summer months due to the heat, high humidity and malaria.[3][4]

So important did Allenby consider the support of the Hedjaz Arabs to the defence of his right flank, that they were substantially subsidised –

“ I think we shall manage the subsidy required as well as the extra £50,000 you require for Northern Operations ... I am urging for another £500,000 additional to the £400,000 en route from Australia and I am sure you will do what you can, through the WO to represent the importance of not risking a delay again in the payment of our Arab subsidy.[7] ” The Ottoman defenders maintained an observation post on El Haud hill which dominates the whole Jordan Valley.[8]

Ottoman Force June 1918 Rifles Sabres Machine guns Art.Rifles [sic] East of Jordan 8050 2375 221 30 VII Army 12850 750 289 28 VIII Army 15870 1000 314 1309 North Palestine Line of Communications 950 – 6 – “ The Turks opposing me are now in greater strength than hitherto – excepting just before the battle of Beersheba–Gaza. His morale, fed on reports of European victories, has risen. The harvest is now reaped, and food is plentiful. My staff estimate that 68,000 rifles and sabres can be kept and fed on this front, during summer. As for redistributing my forces; all my goods are in the shop window. My front, from the Jordan to the Mediterranean, is 60 miles. It is on the whole, a strong line; and I have made, and am making, roads and communications behind it. Still, it is wide – for the size of my force. It is the best line I can hold. Any retirement would weaken it. My right flank is covered by the Jordan; my left by the Mediterranean Sea. The Jordan Valley must be held by me; it is vital. If the Turks regained control of the Jordan, I should lose control of the Dead Sea. This would cut me off from the Arabs on the Hedjaz railway; with the result that, shortly, the Turks would regain their power in the Hedjaz. The Arabs would make terms with them, and our prestige would be gone. My right flank would be turned, and my position in Palestine would be untenable. I might hold Rafa or El Arish; but you can imagine what effect such a withdrawal would have on the population of Egypt, and on the watching tribes of the Western Desert. You see, therefore, that I cannot modify my present dispositions. I must give up nothing of what I now hold. Anyhow, I must hold the Jordan Valley.[9] ” Garrison

Chauvel was given the task of defending the Jordan Valley, but his Desert Mounted Corps had lost the 5th Mounted Yeomanry Brigade and the Yeomanry Mounted Division, both of which, along with most of the British infantry were sent to the Western Front to be replaced by Indian Army infantry and cavalry. This resultant recorganisation required time to work through.[4][10]

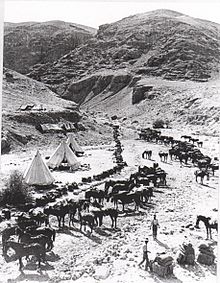

The Jordan Valley was garrisoned in 1918 by the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade (late Imperial Service Infantry Brigade), the Anzac and Australian Mounted Divisions, and arriving on 17 May the 4th and 5th Cavalry Divisions. The took over the outposts in the sector outside the Ghoraniyeh bridgehead while the Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade held the bridgehead.[Note 2] In August these troops were joined at the beginning of the month by the newly formed 1st and 2nd Battalions British West Indies Regiment, in the middle of the month by the first of two Jewish battalions; the 38th Royal Fusiliers and towards the end of August by Indian cavalry units.[4][8][11] This force included a section of the Light Armoured Motor Brigade commanded by Captain McIntyre; the armoured cars had two machine guns mounted on the rear of each car and were camouflaged with bushes while making sorties to attack Ottoman patrols.[12] Allenby had decided to hold the valley with this mainly mounted force because the mobility of mounted troops would enable them to keep the greater proportion of their strength in reserve on the higher ground.[4]

Chauvel's headquarters were at Talaat ed Dumm from 25 April until 16 September and he divided the Jordan Valley into two sectors, each patrolled by three brigades while a reserve of three brigades was maintained.[13][14]

In the garrisoned area of the valley there were two villages; Jericho and Rujm El Bahr on the edge of the Dead Sea; other human habitations included the Bedouin shelters and several monasteries.[15] Arabs chose to evacuate Jericho during the summer months, leaving only the heterogeneous local tribes.[3] In the vicinity of the Dead Sea, the Taamara, a 7,000 strong semi-settled Arab tribe cultivated selected areas of the slopes of the Dead Sea about Wady Muallak and Wady Nur. They husbanded 3,000 sheep, 2,000 donkeys and a few large cattle or camels and travelled to the Madeba district to work as hired carriers.[16]

Conditions in the valley

You will see by the address that we are in the Jordan Valley, and it’s a terrible place. I will never tell anyone to go to hell again; I will tell him to go to Jericho, and I think that will be bad enough! I have been through Jerusalem and Jericho, but did not get much of a look round. We are all going for a swim in the Jordan in a couple of days, and I will try and send you a bottle of water out of it.

We have had some pretty early rises lately. Jacko has been coming over in his planes, bombing and turning his machine guns on us. He did this twice, but the third morning there were 12 of our planes in the sky, so he did not come too close.

I have changed my horse lately, and some of the boys reckon I “slipped on the deal”, but I don’t. I was riding her the other day and you could not see your hand in front of you for dust, which is an everyday occurrence here, when she put her foot in a hole and came down on top of my leg and laid there for a while. It bent my spur and put a gravel rash on my boot, but the old leg was too good – it stood the strain, and I didn’t even drop my pipe out of my mouth.

Well, it’s a hard job to get tobacco over here, so I am going to ask you to send me over three tins every month. Of course, you can make a little parcel of it as well. Also the “Wedderburn Express”; it is about the best old paper to read, although it is called “the rag”.

We have got a change from wet blankets now; we have them dusty and full of grass seeds. They prick a bit, but you soon get used to it, and if you are without sleep for a few nights you don’t mind the pricks at all. I have a new address now, but will still get the letters that are on the way by the old one. J----- was giving me a bit of a “kid” about my letter writing. I don’t know whether you think the same, but I hope the news contained within them will let you see that I am still going strong, and have not forgotten any of you, although you are so far away.”

R. W. Gregson Trooper 2663 undated letter to his family in [17]At 1,290 feet (390 m) below sea level and 4,000 feet (1,200 m) below the mountains on either side of the scorching Jordan Valley, here for weeks at a time, the shade temperature rarely dropped below 100 °F (38 °C) and occasionally reached 122–125 °F (50–52 °C); at the Ghoraniyeh bridgehead 130 °F (54 °C) was recorded. Coupled with the heat, the tremendous evaporation of the Dead Sea which keeps the still, heavy atmosphere moist, adds to the discomfort and produces a feeling of lassitude which is most depressing and difficult to overcome. In addition to these unpleasant conditions the valley swarms with snakes, scorpions, mosquitoes, great black spiders, and men and animals were tormented by day and night by swarms of every sort of fly.[4][18][19]

From Jericho the Jordan River was invisible, about 4 miles (6.4 km) across the almost open plain; being very good going for movement across the valley.[8] Big vultures perch on the chalky bluffs overlooking the river, and storks are seen flying overhead, while wild pigs were seen in the bush. The river contained many fish, and its marshy borders were crowded with frogs and other small animals.[20]

In the spring the land in the Jordan Valley supports a little thin grass, but the fierce sun of early summer quickly scorches this leaving only a layer of white chalky marl impregnated with salt, several feet deep. This surface was soon broken up by the movement of mounted troops into a fine white powder resembling flour, and covering everything with a thick blanket of dust. Roads and tracks were often covered with as much as 1 foot (30 cm) of white powder and traffic stirred this up into a dense, limey cloud which penetrated everywhere, and stuck grittily to sweat-soaked clothes. A white coating of dust would enshroud men returning from watering their horses; their clothes, wet with perspiration which sometimes dripped from the knees of their riding-breeches, and their faces only revealed by sweaty rivulets.[19][21]

During the summer the nights are breathless, but in the early morning a strong hot wind, blowing from the north, sweeps the white dust down the valley in dense choking clouds. By about 11:00 the wind dies down, and a period of deathlike stillness follows, accompanied by intense heat. Shortly afterwards a wind sometimes arises from the south, or violent air currents sweep the valley, carrying “dust devils” to great heights; these continue till about 22:00 after which sleep is possible for a few brief hours.[19]

The troops' general careworn appearance was very noticeable; they were not actually ill but lacked proper sleep and the effects of this deprivation were intensified by the heat, dust, humidity, pressure effect, stillness of the air, and mosquitoes which together with the cumulative effects of the hardships of the two previous years of campaigning caused a general depression. These extremely depressing effects of the region in turn contributed to the debility of troops after a period in the valley. Their shelter was most often just bivouac sheets which barely allowed the men room to sit up; there were a few bell tents in which temperatures reached 125 °F (52 °C). However, although they worked long hours in the hot sun patrolling, digging, wiring, caring for the horses and carrying out anti-mosquito work, heat exhaustion was never a problem (as it had in the Sinai desert; in particular on the second day of the Battle of Romani) as there was easy access to large supplies of pure, cool water for drinking and washing. Springs supplied drinking water and supplies of rations and forage were transported to the valley from Jerusalem. But thirst was constant and very large quantities of fluid; more than 1 imperial gallon (4.5×10−6 LT) were consumed, while meat rations (in the absence of refrigeration) consisted mainly of tins of "bully beef," which was often stewed by the hot conditions while still in the cans, and bread was always dry and there were few fresh vegetables.[4][19][22]

Vegetation

The bush ranged from 4 feet (1.2 m) to the height of a horse; there were numerous Ber trees which have enormous thorns (the traditional “crown of thorns” tree) and big prickly bushes which made it quite easy to rig up shelter from the sun, and near Jericho a woody scrub 3–4 feet (0.91–1.2 m) high, with broad leaves which are woolly on the underside, has fruit similar to apples.[20][23] There was dense jhow jungle on either side of the Jordan River for some 200–300 yards (180–270 m), and the banks were sheer about 5–6 feet (1.5–1.8 m) above water-level which made it impossible to swim horses in the river.[8]

Swimming in the Dead Sea

While in bivouac in the Jordan Valley, it was a common practice when things were quiet, to ride the few miles to Rujm El Bahr, at the northern end of the Dead Sea where the Jordan River runs in, to bathe themselves and their horses. This inland sea is about 47 miles (76 km) long and about 10 miles (16 km) wide with steep mountain country sloping down to the water on each side. The surface of the sea lies 1,290 feet (390 m) below the sea-level of the Mediterranean and the water is extremely salty, containing about 25% mineral salts and is extremely buoyant; many of the horses were obviously perplexed at floating so high out of the water. It has been calculated that 6,500,000 tons of water fall into the Dead Sea daily from various streams, and as the sea has no outlet all of this water evaporates creating the humid heat of the atmosphere in the valley.[15]

Water supply and mosquitoes

The one generous feature of the valley was its water supply; the slightly muddy Jordan River flowed strongly throughout the year in a trough about 100–150 feet (30–46 m) below the valley floor, fed by numerous clear springs and wadis running into it on either side.[4][8] Most New Zealanders enjoyed the physical benefits of bathing in the Jordan at one time or another during the campaign in which a good bath was such a luxury.[20]

In the left sector where the Australian Mounted Division was stationed there were several sources of water; the Jordan River, the Wadi el Auja, and the Wadi Nueiameh, which flowed from Ain el Duk, and into the Jordan at El Ghoraniyeh. The latter wadi was used by the Headquarters of the Valley Defences.[24] The section of the valley patrolled by the Anzac Mounted Division was crossed by the wadis Auja, Mellahah, Nueiameh and the Kelt as well as the Jordan River with several extensive marshes in the jungle on its banks. The nullahs were astonishingly deep, usually with dense vegetation and quite big trees. The area was notorious for subtertian or malignant malaria and in particular the whole valley of the Wadi el Mellahah was swarming with anopheles larvae, the worst kind of mosquitoes.[8][18]

A thousand men cut down the jungle, drained the marshes and swamps, the streams were cleared of reeds which were burnt, canals created so there was no opportunity for standing water, holes were filled in, stagnant pools were oiled and hard standings for the horses were constructed. Even a cultivated area at the source of the Ain es Sultan (Jericho's water supply) was treated by 600 members of the Egyptian Labour Corps over a period of two months. No breeding of the larvae could be demonstrated three days after the work was complete but the areas had to be continually maintained by special malarial squads of the Sanitary Section and the Indian Infantry Brigade. These measures were successful as during the six months to September the incidence of malaria in Chauvel's force was just over five per cent with most cases occurring on the front line or in No Man's Land; while incidence of malaria in the reserve areas was very low.[4][18]

However, despite all efforts, cases of malaria were reported during May and reports of fever steadily developed as the heat and dust increased and the men became less physically fit which lowered their ability to resist sickness. In addition to malaria, minor maladies became very common; thousands of men suffered from blood diseases know as “sand-fly fever” and “five-day fever”, which manifested in excessive temperatures, followed by temporary prostration, and few escaped severe stomach disorders.[25]

Conditions for the horses

The climate did not effect the horses in a marked way but their rations, although plentiful, contained only a small proportion of pure grain with insufficient nutritional value and was too bulky and unpalatable.[26] While others thought the forage was "all that could be desired" and water was plentiful and good. During mid summer when iron was too hot to handle and a hand placed on the back of a horse was positively painful, yet in the dust, the heat and the many diseases, in particular Surra fever which carried by the Surra fly which, in 1917 decimated the Ottoman transport killing as many as 42,000 camels in the Jordan Valley, the horses survived.[27]

They did not thrive, however, and they came out of the valley in poor condition, due mainly due to insufficient number of men to water, feed and groom them and the conditions were unfavourable for exercise, which is essential for keeping horses in good health and condition. There was on average one man to look after six or seven horses, and at times in some regiments there was only one man for every 15 horses after the daily sick had been evacuated and men for outposts, patrols and anti-malarial work had been found.[10]

Occupation

German and Ottoman aerial bombing raids

Bivouacs were bombed during the first few days in the Jordan Valley, but the Indian Army cavalry horse lines in the bridgehead were not attacked, either by bomb-dropping or machine-gunning.[8] Both bivouacs and horse lines of the light horse and mounted rifle brigades were attacked. At dawn on Tuesday 7 May a big bombing raid by nine German aircraft were attacked by heavy rifle and machine gun fire. One bomb fell in the bivvies of the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance where only two were wounded, but metal fragments riddled the tents and blankets. Stretcher bearers brought in 13 wounded in a matter of minutes and what remained of the Field Ambulance horses after the attack on 1 May at Jisr ed Damieh (see Second Transjordan attack on Shunet Nimrin and Es Salt (1918)) were only 20 yards (18 m) away and 12 were wounded and had to be destroyed.[28][Note 3] Another raid the next morning resulted in only one casualty although more horses were hit.[29]

These bombing raids were a regular performance every morning for the first week or so; enemy aircraft flying over were attacked by anti-aircraft artillery, but they ceased after Allied aircraft bombed their aerodrome.[30]

Relief of the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade

On 10 May the 4th Light Horse Brigade received orders to relieve the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade.[31]

Long-range German and Ottoman guns

Spasmodic bursts of long-range shells fired from a German naval pattern 6 inches (15 cm) gun, occurred throughout the British Empire occupation of the Jordan Valley. Some 30 shells were fired at various camps and horse lines in the neighbourhood during the first week. During June they steadily increased artillery fire on the occupied positions, freely shelled the horse lines of the reserve regiment along the Auja, and at times inflicting severe casualties.[21][32][33]

The gun was deployed north-west of British Empire line in the valley and shelled Ghoraniyeh, Jericho, and other back areas at a range of some 20,000 yards (18,000 m). This long-range gun was also reported firing from well disguised positions in the hills east of the Jordan River on British Empire camps and horse lines, with the benefit of reports from German Taube aircraft, with a black iron cross under each wing. The gun could fire at targets over 12 miles (19 km) away; on one occasion shelling Jericho, after which the gun was called "Jericho Jane." At the end of the war when this gun was captured, it was found to have been about 18 feet (5.5 m) long and the pointed high explosive shells and their charge-cases were nearly 6 feet (1.8 m) long. In July two more guns of a similar caliber were deployed in about the same position; north-west of the British Empire line in the valley.[21][32][34][Note 4]

Ottoman artillery – July reinforcements

The Ottoman forces in the hills overlooking the Jordan Valley received considerable artillery reinforcement early in July, and pushed a number of field guns and heavy howitzers southwards, east of the Jordan, and commenced a systematic shelling of the troops. Camps and horse lines had to be moved and scattered about in sections in most inconvenient situations along the bottoms of small wadis running down from the ridge into the plain. The whole of the Wadis el Auja and Nueiameh was under the enemy’s observation either from Red Hill and other high ground east of the Jordan or from the foothills west and north-west of Abu Tellul, and took full advantage of this to shell watering places almost every day even though the drinking places were frequently changed. Every effort was made to distract their attention by shelling their foothills positions vigorously, during the hours when horses were being watered. But the dense clouds of dust raised by even the smallest parties of horses on the move, generally gave the game away, and the men and horses were constantly troubled by enemy artillery and numerous times severe casualties were suffered by these watering units.[32][33][35]

Tour of duty

“ Troops were sent out on 24 hour tours of duty; the troop detailed for duty parading mounted, carrying a full supply of ammunition and rations, at Regimental Headquarters where the troop-leader would receive his orders. Moving off, they would march perhaps 8–9 miles (13–14 km), often in single file, crossing the deep gullies which intersect the country near the river and after watering the horses en route if possible, they would arrive to relieve the other troops on their post at about 18:00 or at dusk. The relieved troop would hand over any information regarding enemy patrols, posts, or ranges to important points, and then set out on their march back to camp. The officer or sergeant in charge of the troop would then look over the ground and decide on the best spot for the horses and arrange the disposition of the troop including a listening post to be occupied during the night, in front of the general position and the site for the best deployment of the Hotchkiss automatic rifle.[Note 5] Sentries would be posted, and horse-pickets would be required to watch the horses, and, if a hollow screened from observation could be found, the men would boil up their billies and make a rough meal while the horses were fed. On work of this kind the horses always remained saddled during the night, and were usually ‘linked’ – that is, tied together by their head-ropes, so that in an emergency they could quickly be got out.

On post, the Hotchkiss would always be placed where it could do the most damage, and all night a man would be lying near it, with the first strip inserted in the breach, ready at a moment’s notice. The night might pass uneventfully – on the other hand, rifle fire in front, and the ricocheting of bullets overhead, might give all hands an anxious time as they peered into the darkness in the hope of information from their listening post in front. Perhaps the firing would die down, and silence reign once more, except for the occasional restless movements of the horses, the rolling of a dislodged clod down a hillside, or the weird baying of jackals. Thus the night might pass or a sinister stillness might suddenly be broken by a crash of rifle fire near at hand, and the hurried tumbling in of panting men from the listening post, with information of the direction of an enemy attack. Then, if the enemy appeared to be in greatly superior numbers from their rifle flashes and vaguely-seen dim forms, each man would know a stern fight was before him. For if the orders were to hold the position, it must be some hours before the troop could be reinforced from the Regiment, miles away.

Assuming that our troop weather the hours of darkness with nothing more eventful occurring than a few stray shots, and perhaps the sounds of an enemy patrol moving somewhere in front, the eerie hour of dawn would see a few tired figures creeping in, as the men of the listening post return to their troop ready for what the day may bring forth. If things are quiet, this is the time for relaxation after a more or less sleepless night, for now one sentry, with glasses, is all that need be on watch, and the remainder set about feeding themselves and horses somewhere under cover.

The day may give opportunities of ‘potting’ at Turks if they show themselves in range, or the troop may see enemy aeroplanes come over to reconnoitre the British bivouacs for signs of any hostile movements, and interestedly watch them running the gauntlet as the white puffs of shrapnel or black splotches of high explosive anti-aircraft shells burst around them thousands of feet up in the air. This interest, however, may be tempered with a certain amount of bad language from the troop if the enemy planes happen to be about half way between them and the British anti-aircraft guns. For the air will presently fill with a slowly growing musical note as ‘spare parts’ in the form of shrapnel, shell fragments, and nose-caps, begin to fall, with a whirring noise, from the sky to the ground all around them; the spent parts of the exploded shells fired at the enemy airmen, still with a sufficient momentum in falling to knock a man out.

The Turk may have located this post and decided to shell it, when soon after it is light there will be a muffled roar in the distance, a whine that quickly grows to a hissing shriek, and with a shocking crash in the stillness a shell bursts near at hand. Every man gets behind whatever cover is available, and anxious eyes watch the horses in the hope that they will not be hit. A sigh of relief goes round as the enemy shots go wider and wider with each successive shell, apparently searching the ground for the exact location of the post. Then perhaps the shell-fire will cease, ‘Jacko’ as our men call the Turk, having decided that the expenditure of more ammunition on such an unsatisfactory target is not worth while.

Later in the day the post may be visited by an artillery officer keen to hear of any new targets that our men may have located before them on enemy ground, or perhaps even a colonel or general may appear, wishing to acquaint himself with all the features of the front he is responsible for.

So the day draws to a close, until as the dust cloud heralding the arrival of the relieving troop appears in the distance, the order is given ‘Saddle Up!’ (it being usual to off-saddle by day), and then ‘Get Ready to Move!’ [36]

” Air support

April – May

No 1 Squadron Australian Flying Corps moved forward in the last week of April from Mejdel to a new aerodrome outside Ramleh to focus on the Nablus area and during a reconnaissance of the horse-shoe road on 7 May a careful count of all camps was made. The western of the two aerodromes at Jenin to the north of the Judean hills was found to have an additional seven more hangars and on the way home they forced down two Albatros scouts over Tul Keram. A British formation of nine machines dropped nearly a ton of bombs at Jenin two days later, on 9 May, pitting the landing-ground and the railway station, and burning several hangars. Most of the aircraft of the German No. 305 Squadron were damaged in this raid but a Rumpler had an aerial fight with the British aircraft over Jenin aerodrome.[37]

On 13 May four machines of the No. 1 Squadron AFC, in a systematic sweep over the Jisr ed Damieh region took nearly 200 photographs, which enabled a new map to be drawn. Aerial photographs for a new Es Salt sheet were also taken and also for a new map of the Samaria–Nablus region and on 8 June the first British reconnaissance of Haifa, examined the whole coast up to that point. Regular reconnaissances took place over Tul Keram, Nablus and Messudie railway stations and the Lubban–road camps on 11 and 12 June when numerous aerial engagements took place; the superior Bristol Fighter proving superior to the German Rumpler.[38]

June

German aircraft often flew over the British Empire lines at the first light and were particularly interested in the Jericho and lower Jordan area where on 9 June a highflying Rumpler, was forced to land near Jisr ed Damieh, after fighting and striving during five minutes of close combat at 16,000 feet to get the advantage of the Australian pilots. These dawn patrols also visited the Lubban–road sector of the front (north of Jerusalem on the Nablus road) and the coast sector.[39]

Increasingly the air supremacy won in May and June was used to the full with British squadrons flying straight at enemy formations whenever they were sighted while the opposition often fought only if escape seemed impracticable. The close scouting of the Australian pilots which had become a daily duty was, on the other side, utterly impossible for these German airmen who often flew so high that its likely their reconnaissances lacked detail; owing to the heat haze over the Jordan Valley, Australian airmen found reconnaissance even at 10,000 feet difficult.[40]

This new found British and Australian confidence led to successful machine gun attacks on Ottoman ground–troops which were first successfully carried out during the two Transjordan operations in March and April. They inflicted demoralising damage on infantry, cavalry, and transport alike as at the same time as German airmen became more and more disinclined to fly. British and Australian pilots in bombing formations first sought out other enemy to fight; they were quickly followed by ordinary reconnaissance missions when rest camps and road transport in the rear became targets for bombs and machine guns.[41]

In mid-June British squadrons, escorted by Bristol Fighters, made three bomb raids on the El Kutrani fields dropping incendiary bombs as well as high explosives bombs, causing panic among Bedouin reapers and Ottoman cavalry which scattered, while the escorting Australians lashed with machine-gun fire the unusually busy El Kutrani railway station and a nearby train. While British squadrons were disrupted the Moabite harvest gangs, bombing raids from No. 1 Squadron were directed against the grain fields in the Mediterranean sector. On the same day of the El Kutrani raid; 16 June the squadron sent three raids, each of two machines, with incendiary bombs against the crops about Kakon, Anebta, and Mukhalid. One of the most successful dropped sixteen fire-bombs in fields and among haystacks, set them alight, and machine gunned the workers.[42]

July

Daily observations of the regions around Nablus (headquarters of the Ottoman 7th Army) and Amman (on the Hedjaz railway) were required at this time to keep a close watch on the German and Ottoman forces' troop movements. There were several indications of increased defensive preparations on the coastal sector; improvements were made to the Afule to Haifa railway and there was increased road traffic all over this district while the trench system near Kakon was not being maintained. The smallest details of roads and tracks immediately opposite the British front and crossings of the important Nahr Iskanderuneh were all carefully observed.[43]

Flights were made down the Hedjaz railway on 1 July to El Kutrani where the camp and aerodrome were strafed with machine gun fire by Australians and on 6 July at Jauf ed Derwish they found the garrison working to repair their defences and railway culverts, after the destruction of the bridges over the Wady es Sultane to the south by the Hedjaz Arabs, which cut their railway communications. When Jauf ed Derwish station north of Maan was reconnoitred, the old German aerodrome at Beersheba was used as an advance landing-ground. Also on 6 July aerial photographs were taken of the Et Tire area near the sea for the map makers. Two days later Jauf ed Derwish was bombed by a British formation which flew over Maan and found it strongly garrisoned. No. 1 Squadron’s patrols watched the whole length of the railway during the first fortnight of July; on 13 July a convoy of 2,000 camels south of Amman escorted by 500 cavalry, moving south towards Kissir was machine gunned scattering the horses and camels, while three more Bristol Fighters attacked a caravan near Kissir on the same day; Amman was attacked several days later.[44]

Several aerial combats occurred over Tul Keram, Bireh, Nablus and Jenin on 16 July and attacked a transport column of camels near Arrabe, a train north of Ramin and three Albatros scouts aircraft on the ground at Balata aerodrome. Near Amman 200 cavalry and 2,000 camels which had been attacked a few days previously, were again attacked, and two Albatros scouts were destroyed during aerial combat over the Wady el Auja.[45]

On 22 July Australian pilots destroyed a Rumpler during a dawn patrol south west of Lubban after aerial combat and on 28 July two Bristol Fighers piloted by Australians fought two Rumpler aircraft from over the outskirts of Jerusalem to the upper Wady Fara; another Rumpler was forced down two days later.[46]

On 31 July a reconnaissance was made from Nablus over the Wady Fara to Beisan where they machine gunned a train and a transport park near the sstation. Then they flew north to Semakh machine gunning troops near the railway station and aerodrome before flying back over Jenin aerodrome. During the period of almost daily patrols almost 1,000 aerial photographs were taken from Nablus and Wady Fara up to Beisan and from Tul Keram north covering nearly 400 square miles (1,000 km2). Enemy troops, roads and traffic were regularly attacked even by photography patrols when flying low to avoid enemy anti-aircraft fire.[47]

August

On 5 August the camps along the Wady Fara were counted and small cavalry movements over Ain es Sir were noted, chased down an Albatros scout and returning over the Wady Fara machine gunned a column of infantry and some camels; these camps were harassed a few days later. A formation of six new Pfalz scout was first encountered over Jenin aerodrome on 14 August when it was found they were inferior to the Bristol aircraft in climbing ability and all six were forced after aerial combat to land. Rumpler aircraft were successfully attacked on 16 and 21 August and on 24 August a determined attack by eight German aircraft on two Bristol Fighters defending the British air screen between Tul Keram and Kalkilieh was defeated and four of the enemy aircraft were destroyed.[48]

Medical support

In May the Anzac Field Laboratory was established 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north west of Jericho at the foot of the hills.[49] The 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance relieved the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade Field Ambulance shortly after 10 May and about this time daily shade temperatures were registered in the ambulance tents between 109–110 °F (43–43 °C) and often as high as 120 °F (49 °C).[27][29] Friday 31 May 1918, was the hottest day yet, the temperature reached 108 °F (42 °C) in the operating tent and 114 °F (46 °C) outside in the shade. A terrible night followed; close, hot and still, then a tearing wind with clouds of dust from 02:00 to 08:00 smothered everything in dust.[50]

In the five weeks between 2 May and 8 June, 616 sick men were evacuated from the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance, representing one third of the men of the brigade. During the same period, the field ambulance treated about the same number for dressings and minor ailments some of whom were kept in hospital for a few days and returned to their units. So effectively, in five weeks, the field ambulance cared for the equivalent of two regiments or two thirds of the total brigade.[51] Yet in general the Force's standard of health was very high.[52]

Apart from the endemic prevalence of malaria a certain amount of dysentery occurred, and a few cases of enteric, relapsing fever, typhus, and smallpox were also seen and sand-fly fever was not very uncommon.[53] Boils were a relatively minor infliction which were inevitable in the dust, heat and sweat of the Jordan Valley. They might begin where shirt collars rubbed the backs of necks, then spread to the top of the head and possibly the arm pits and buttocks. They were very painful and were treated by lancing or hot foments sometimes applied hourly and requiring a day or two in hospital. These foments were made from a wad of lint wrapped in a towel and held in boiling water; when hot the towel was taken out and wrung thoroughly until the lint was as dry as possible when it was quickly slapped straight on the boil – if it was allowed to cool even slightly it would be ineffective.[54]

Field Ambulances % Average weekly admitted Average weekly evacuated January .95 .61 February .70 .53 March .83 .76 April 1.85 1.71 May 1.94 1.83 June 2.38 2.14 July 4.19 3.98 August 3.06 2.91 to 14 September 3.08 2.52 The Anzac Mounted Division which had had the longest and severest campaigning prior to garrisoning the valley, also served in the Jordan Valley for the longest period.[26] Of the many hundreds of New Zealanders sent to hospital from the Jordan Valley with malaria, many died, many recovered in hospital but later suffered a relapse and went to hospital again, many men were invalided to New Zealand as a result of malaria, with their health badly undermined. At this time, all available reinforcements were in demand.[56]

Malaria

Wearing only shorts and putties, and short sleeved shirts, we were bitten unmercifully by mosquitoes, until our arms and legs looked like sieves, even when sleeping under a mosquito net. All troops have been issued with mosquito nets – big double bed size, one to each two men. When stretched out they can easily cover a two–man bivvy. But even when well tucked in some mosquitoes still managed to get in for a bite somehow or other.

From May onwards an increasing and ultimately heavy wastage was brought about by infection from the parasite of malaria – both Plasmodium vivar (benign tertian) and Plasmodium fakiparum (malignant tertian), with a small incidence of quartan - in spite of determined, well-organised, and scientifically controlled measures of prevention.[53]

Malaria struck during the week of 24 to 30 May and although a small percentage of men seemed to have an inbuilt resistance, many did not and the field ambulances had their busiest time ever when a very high percentage of troops got malaria; one field ambulance treated about 1,000 patients at this time.[57]

Minor cases of malaria are kept at the field ambulance for two or three days in the hospital tents, and then sent back to their units. More serious cases, including all the malignant ones, were evacuated as soon as possible, after immediate treatment. All cases got one or more injections of quinine.[50]

Ice began to be delivered daily by motor lorry from Jerusalem to treat the bad cases of malignant malaria; it travelled in sacks filled with sawdust, and with care lasted for 12 hours or more. Patients in the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance were as a result, given iced drinks which to them, appeared incredible. When a serious case arrived with a temperature of 104–105 °F (40–41 °C) ice wrapped in lint was packed all round his body to practically freeze him; his temperature was taken every minute or so and in about 20 minutes when his temperature may have dropped to normal he was wrapped, shivering in a blanket, when the tent temperature was well 100 °F (38 °C), and evacuated by motor ambulance to hospital in Jerusalem, before the next attack.[50]

One such evacuee was A. E. Illingworth, Trooper 1682a who had been born at Gurley, NSW in 1875 and farmed at "Oaklands", Narrabri West, landed at Suez on 19 January 1917 aged 42 years and was taken to the 12th Light Horse Regiment training camp at Moascar. On 3 March 1917 he transferred to the 4th Light Horse Regiment at Ferry Post and was in the field until he became ill from pyrexia on 8 June 1918 when he was admitted to 31 General Hospital, Abbassia on 15 June. After treatment he rejoined his regiment on 20 July at Jericho and remained in the field until returning to Australia on the "Essex" on 15 June 1919. He died at Narrabri in May 1924.[58]

Between 15 May and 24 August the 9th and 11th Light Horse Regiments, participated in a quinine trial; every man in one squadron in each regiment was given five grains of quinine daily by mouth and the remainder none. During the period 10 cases of malaria occurred in the treated squadrons while 80 occurred in the untreated men giving a ration of 1:2.3 cases.[59]

Trip to hospital

For the wounded and sick the trip to base hospital in Cairo 300 miles (480 km) away was a long and difficult one during which it was necessary for them to negotiate many stages.

- From his regiment the sick man would be carried on a stretcher to the Field Ambulance, where his case would be diagnosed and a card describing him and his illness was attached to his clothing.

- Then he would be moved to the Divisional Casualty Clearing Station, which would be a little further back in the Valley, close to the motor road. #From there he would be placed, with three other stretcher cases, in a motor ambulance, to make the long journey through the hills to Jerusalem, where he would arrive coated in dust.

- In Jerusalem he would be carried into one of the two big buildings taken over by the British for use as casualty clearing stations. His medical history card would be read and treatment given him, and he might be kept there for a couple of days. (Later, when the broad-gauge line was through to Jerusalem, cases would be sent southwards in hospital train.)

- When he was fit enough to travel, his stretcher would again make up a load in a motor ambulance to Ludd, near the coast on the railway three or four hours away over very hilly, dusty roads.

- At Ludd the patient would be admitted to another casualty clearing station, where he would perhaps be kept another day or two before continuing his journey southwards in a hospital train.

- The hospital train would take him to the stationary hospital at Gaza, or El Arish or straight on to Kantara.

- After lying in a hospital at Kantara East for perhaps two or three days, he would be carried in an ambulance across the Suez Canal to Kantara West.

- The last stage of his journey to a base hospital in Cairo was on the Egyptian State Railways.[60]

Rest camp

As the result of the good effects of the rest camp on the beach at Tel el Marakeb in 1917, an "Ambulance Rest Station" for Desert Mounted Corps was established in the grounds of a monastery at Jerusalem. This was staffed in turn by personnel from the immobile sections of corps' ambulances. A good supply of tents and mattresses was obtained, extras in the way of food provided, and the troops put under conditions differing as much as possible from the ordinary regimental life. Valuable help was given by the Australian Red Cross Society in the supply of games, amusements, and comforts. The men sent to this rest camp, including Indian cavalrymen, were those run down or debilitated after minor sickness.[61]

During the Palestine advance the system of leave to the Australian Mounted Division's Rest Camp at Port Said was stopped but recommenced at the beginning of January, 1918, and throughout the period spent in the Jordan Valley quotas averaging some 350 men were sent there every ten days which gave the men seven days clear rest, under very satisfactory conditions.[62]

Return trip from rest camp to the Jordan

The return journey was very different from coming down in a hospital train as a draft usually travelled at night, in practically open trucks with about 35 men packed into each truck including all their kits, rifles, 48 hours’ rations, and a loaded bandolier. They would arrive at Ludd in the morning after a sleepless night in a bumping, clanking train where they would have time for a wash and a scratch meal before moving on by train to Jerusalem where the draft would be accommodated for perhaps a night or two at the Desert Mounted Corps rest camp, 1 mile (1.6 km) or so from the station. From there they would be despatched in motor lorries down the hill to Jericho, where led horses would be sent in some miles, from the brigade bivouac, to meet them and carry them back to their units.[63]

Reliefs

Relief of the Anzac Mounted Division

On 16 May two brigades of the Anzac Mounted Division were relieved of their duties in the Jordan Valley and ordered two weeks rest in the hills near Bethlehem. The division trekked up the winding white road, which ran between Jericho and Jerusalem, stopping at Talaat Ed Dum, a dry, dusty bivouac near the Good Samaritan's Inn where, Lieutenant General Chauvel, commander of the Jordan Valley sector, had his headquarters beside the Jericho road about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) to the east. The brigades of the Anzac Mounted Division remained there until 29 May the following morning moved through Bethany, skirted the walls of the Holy City, and through modern Jerusalem and out along the Hebron road to a bivouac site in the cool mountain air at Solomon's Pools about half way between Jerusalem and Hebron.[64][65][66] Only the 1st Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigades left the Jordan Valley at this time; the 2nd Light Horse remained; they left the valley for Solomon's Pools on 5 June and returned on 22 June.[67][68]

Jerusalem tourists

Even when nominally ‘resting’ a trooper’s time was never his own – horse-pickets still had to do their turn every night, guards, pumping parties for watering the horse and endless other working parties had to be supplied.[64] The horses were watered twice a day at the “Pools of Solomon” great oblong cisterns of stone, some hundreds of feet long, which were still in good condition. The pumps were worked by the pumping parties on a ledge in one of the cisterns pushing the water up into the canvas troughs above, where the horses were be brought in in groups. The hand-pumps and canvas troughs were carried everywhere, and where water was available were quickly erected.[69]

During their stay at Solomon's Pools the men attended a celebration of the King's Birthday on 3 June, when a parade was held in Bethlehem and the inhabitants of Bethlehem were invited to attend. They erected a triumphal arch decorated with flowers and flags and inscribed: "Bethlehem Municipality Greeting on the Occasion of the Birthday of His Majesty King George V" at the entrance to the square, in front of the Church of the Nativity.[70]

While at Solomon's Pools, most of the men got the opportunity of seeing Jerusalem where many photographs of historical spots were taken and sent home; there some gained the impression that the light horsemen and mounted riflemen were having some sort of a ‘Cook’s tour.’ Naturally most of the photos were taken during these short rest periods as the long months of unending work and discomfort gave rare opportunities or inclinations for taking photos.[64]

Return of the Anzac Mounted Division

On 13 June the two brigades moved out to return via Talaat ed Dumm to Jericho, reaching their bivouac area in the vicinity of the Ain es Duk on 16 June. Here a spring gushes out a mass of stones in an arid valley and within a few yards became a full flowing stream of cool and clear water, giving a flow of some 200,000 imperial gallons (0.89 LT) per day. Part of this stream ran across a small valley along a beautiful, perfectly preserved, Roman arched aqueduct of three tiers.[71]

For the rest of June, while the Australian Mounted Division was at Solomon's Pools, the Anzac Mounted Division held the left sector of the defences, digging trenches and regularly patrolling the area including occasional encounters with enemy patrols.[27]

Relief of the Australian Mounted Division

The relief of the Australian Mounted Division by the Anzac Mounted Division was ordered on 14 June and by 20 June the command of the left sector of the Jordan Valley passed to the commander of the Anzac Mounted Division from the commander of the Australian Mounted Division who took over command of all troops at Solomon's Pools. Over several days the 3rd and 4th Light Horse and 5th Mounted Brigades were relieved of their duties and sent to Bethlehem for a well earned rest.[72][73]

On Sunday 16 June, I visited the nearby Monastery of the Enclosed Garden,or Solomon's Garden. It was very interesting and beautiful, with all types of trees, including fruit trees, enclosed within huge, rock–built walls. I then visited Bethlehem and was shown over the Monastery of Saint Joseph by the Mother Superior. Also visited the Church of the Nativity, where they claim you can still see the manger where Christ lay as a baby. You have to peer at it though a narrow slit between two rocks, to prevent it from damage and souveniring by tourists and pilgrims.

Staff Sergeant Hamilton [74]The 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance moved out at 17:00 on Sunday 9 June in a terrific storm and three hours later arrived at Talaat ed Dumm halfway to Jerusalem where they spent a couple of days; it was exactly six weeks since the brigade had first gone to the Jordan Valley.[72]

On Thursday 13 June the Field Ambulance packed up and moved onto the Jerusalem road at about 18:00 travelling on the very steep up-hill road till 23:00; on the way picking up four patients. They rested till 01.30 on Friday, before going on to arrive at Jerusalem, about 06:00, then on to Bethlehem, and two miles beyond, reached Solomon’s Pools by 09:00. Here the three huge rock-lined reservoirs, built by King Solomon about 970 BC to supply water by aqueducts to Jerusalem, were still in reasonable repair as were the aqueducts which were still supplying about 40,000 gallons of water a day to Jerusalem.[75]

Here in the uplands near Solomon's Pools, the sunny days were cool, and at night men who had suffered sleepless nights on the Jordan enjoyed the mountain mists and the comfort of blankets.[76] The Australian Mounted Division Train accompanied the division Bethlehem to repair the effects of the Jordan Valley on men, animals and wagons.[77]

Return of the Australian Mounted Division

Desert Mounted Corps informed the Australian Mounted Division at 10:00 on Friday 28 June that an attempt was to be made by the enemy to force a crossing over the Jordan in the area south of the Ghoraniyeh bridgehead.[73] The division packed up quickly and began its return journey the same day at 17:30; the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance arriving at Talaat ed Dumm or the Samaritan's Inn at 15:00 on Saturday 29 June 1918.[78] And at dusk on Sunday 30 June the division moved out and travelled till midnight then bivouacked back in the Jordan Valley, just three weeks after leaving.[66]

On Monday 1 July the 4th Light Horse Brigade "stood to" all day near Jericho until 20:00, when in the dark, they moved northwards about 10 miles (16 km) to a position in a gully between two hills, just behind the front line. The horses were picqueted and the men turned in about 23:00. Next morning the whole camp was pitched, the field ambulance erecting their hospital and operating tents, and horse lines were put down and everything was straightened up. The weather was still very hot but the daily early morning parade continued, followed by all the horses being taken to water. It was necessary to go about 5 miles (8.0 km), to water and back, through terrible dust, which naturally the horses churned up so that it was difficult to see the horse in front. The men wore goggles and handkerchiefs over their mouths to keep out some of the dust, but it was a long, dusty, hot trip.[79]

the flies used to drive us mad, but now there are hardly any left, the heat has killed them. Next month is to be the worst, I believe, I can't see how our horses are going to stand it. Several have died from snake-bite. We have to camp with our horses in the wady beds and hollows to get cover from the shell fire and down here, of course the heat intensifies and if there is any moving air up top, we don't get it. The horses have cut the place up so it is a heap of fine dust ankle deep, we must be full of it inside.

The reinforcements can't stand it, they last about a week and off they go to hospital. The old hands stick it out, nothing short of a bullet will put them in hospital. The new chaps go down … and are not much help to us … some of them have hearts like chickens. One man with three years' service is worth half a dozen of them. Am in good health myself, don't seem able to get sick at all.

Baly[80]Each day during the middle of summer in July, the dust grew deeper and finer, the heat more intense and the stagnant air heavier and sickness and sheer exhaustion became more pronounced, and it was noticed that the older men were better able to resist the distressing conditions. Shell-fire and snipers caused casualties which were, if not heavy, a steady drain on the Australian and New Zealand forces, and when men were invalided, the shortage of reinforcements necessitated bringing them back to the valley before their recovery was complete.[81][Note 7]

Mounted patrols were a daily occurrence when skirmishes and minor actions often happened and in the bridgeheads there was generally some fighting going on. A small fleet of armed launches used for patrolling the eastern shore and for keeping up a precarious communication with the Arab forces of the Sherif Feisal, were maintained and guarded on the Dead Sea.[82]

Among the many wounded while on patrol during tours of duty, was Lance Corporal J. A. P. (Jim) McIntyre, regimental number 1621. He had been made a temporary corporal at Beersheba on 3 November 1917 and was promoted to that rank at Solomon Pools on 24 June 1918. He was wounded in action when on patrol near Auja on 22 July 1918 and admitted to the 31 General Hospital, Abbassia for treatment to a bullet wound in his abdomen; he was on the dangerously ill from 8 August until 17 August. He returned to Australia on "Leicestershire" 22 December 1918.[83]

During the height of summer in the heat, the still atmosphere, and the dense clouds of dust, there was constant work associated with the occupation; getting supplies, maintaining sanitation as well as front line duties which was usually active. The occupation force was persistently shelled in advanced positions on both sides of the river, as well as at headquarters in the rear.[84]

From mid July, after the Action of Abu Tellul, both sides confined themselves to artillery activity, and to patrol work, in which the Indian Cavalry, excelled.[24]

Relief and return of the Anzac Mounted Division

The Anzac Mounted Division was in the process of returning to the Jordan Valley during 16 – 25 August after its second rest camp at Solomon's Pools which began at the end of July – beginning of August.[85][86]

Australian Mounted Division move out of the valley

On 9 August the division was ordered to leave the Jordan Valley exactly six weeks after returning from Solomon's Pools in July and 12 weeks since they first entered the valley.[54] They moved across Palestine in three easy stages of about 15 miles (24 km) each, via Talaat ed Dumm, Jerusalem and Enab to Ludd, about 12 miles (19 km) from Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast; each stage beginning about 20:00 in the evening and completed before dawn to avoid being seen by enemy reconnaissance aircraft. They arrived at Ludd about midnight on 14/15 August; pitched their tents in an olive orchard and put down horse lines.[87] The following day camps were established; paths were made and gear in transport wagons unloaded and stored.[88]

Final days of occupation

From the departure of the Australian Mounted Division steps were taken to make it appear that the valley was still fully garrisoned. These included building a bridge in the valley and infantry were marched into the Jordan Valley by day, driven out by motor lorry at night, and marched back in daylight over and over again and 15,000 dummy horses were made of canvas and stuffed with straw and every day mules dragged branches up and down the valley (or the same horses were ridden backwards and forwards all day, as if watering) to keep the dust in thick clouds. Tents were left standing and 142 fires were lit each night.[89][90]

Although the maintenance of so large a mounted force in the Jordan Valley was expensive, it was less costly than having to re-take the valley prior to the Battle of Megiddo and the force which continued to garrison the valley played an important part in the battle strategy.[35] While losses from malaria were considerable, the heat intense, and the dust worse than the troops had ever experienced, the ultimate successes of Allenby's September attacks, more than justified the cost.[91]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ The Ghoraniyeh bridgehead was just 15 miles (24 km) from Jerusalem direct. [Maunsell 1926 p. 194]

- ^ The two veteran Imperial Service brigades had been in the theater since 1914 and seen service from the Suez Canal onwards. [Falls 1930 Vol. 2 Part II p. 424]

- ^ The casualty percentage for the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance was at this time was 33% which is high for a support unit. [Hamilton 1996 p. 120]

- ^ A similar gun used during the Gallipoli campaign had been located on the Asiatic side of the Dardanelles and had been known as "Asiatic Annie." [McPherson 1985 p. 139]

- ^ Each troop in the New Zealand Brigade carried a Hotchkiss automatic rifle, with had a section of four men trained in its use. In situations where the troop-leader often wished he had a hundred men instead of twenty-five or less, it was an invaluable weapon. The gun is air-cooled, can fire as fast as a machine-gun, but has the advantage of a single-shot adjustment, which will often enable the man behind the gun to get the exact range by single shots indistinguishable from rifle fire, and then to pour in a burst of deadly automatic fire. The gun will not stand continued use as an automatic without overheating, but despite this it is a most useful weapon, light enough to be carried by one man dismounted. On trek, or going into action, a pack-horse in each troop carried the Hotchkiss rifle, spare barrel, and several panniers of ammunition, while a reserve of ammunition was carried by another pack-horse for each two troops. The ammunition was fed into the gun in metal strips, each containing thirty rounds. [Moore 1920 p. 120]

- ^ Hamilton had only recently been promoted to Staff Sergeant when his pay was increased to 14 shillings a day. [Hamilton 1996 p. 119]

- ^ The 20th Infantry Division, the 22nd Mounted Brigade and the other cavalry regiments serving at this time in the Jordan Valley would have suffered similarly.

- Citations

- ^ Bruce 2002 p. 203

- ^ a b Hughes 2004 p. 160

- ^ a b c d e f g h Powles 1922 pp. 222–3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Keogh 1955 p. 228

- ^ Wavell 1968 pp. 188–9

- ^ a b Woodward 2006 p. 183

- ^ Letter Wingate to Allenby; 5 July 1918 in Hughes 2004 pp. 167–8

- ^ a b c d e f g Maunsell 1926 p. 199

- ^ Allenby letter to Wilson 15 June 1918 in Hughes 2004 p. 163

- ^ a b Blenkinsop 1925 p.228

- ^ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 Part II pp. 423–4

- ^ Scrymgeour 1961 p. 53

- ^ Powles 1922 pp. 223–4

- ^ Hill 1978 p. 157

- ^ a b Moore 1920 pp. 116–7

- ^ Secret 9/4/18

- ^ Holloway 1990 pp. 212–3

- ^ a b c Powles 1922 pp. 260–1

- ^ a b c d Blenkinsop 1925 pp. 227–8

- ^ a b c Moore 1920 p. 118

- ^ a b c Moore 1920 p. 146

- ^ Downes 1938 pp. 700–3

- ^ Maunsell 1926 pp. 194, 199

- ^ a b Preston 1921 p. 186

- ^ Gullett 1941 p. 643

- ^ a b Falls 1930 Vol. 2 Part II p. 424

- ^ a b c Powles 1922 p. 229

- ^ Hamilton 1996 pp. 119–20

- ^ a b Hamilton 1996 p. 120

- ^ Maunsell 1926 p. 194

- ^ 4th LHB War Diary AWM4, 10-4-17

- ^ a b c Preston 1921 pp. 186–7

- ^ a b Gullett 1941 p. 669

- ^ Scrymgeour 1961 p.54

- ^ a b Blenkinsop1925 pp. 228–9

- ^ Moore 1920 pp.118–23

- ^ Cutlack 1941 p. 122

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 122–3, 126–7

- ^ Cutlack 1941 p. 127

- ^ Cutlack 1941 p. 128

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 128–9

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 125–6

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 140

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 135–6

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 138

- ^ Cutlack 1941 p. 139

- ^ Cutlack 1941 p. 141–2

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 142–4

- ^ Downes 1938 p. 699

- ^ a b c d Hamilton 1996 p.122

- ^ Hamilton 1996 pp. 123–4

- ^ Falls 1930 Vol. 2 Part II p. 425

- ^ a b Downes 1938 p. 705

- ^ a b Hamilton 1996 p. 133

- ^ Downes 1938 p. 712

- ^ Moore 1920 p.142

- ^ Hamilton 1996 pp. 121–2

- ^ G. Massey 2007 p. 58

- ^ Downes 1938 p. 707

- ^ Moore 1920 pp.142-4

- ^ Downes 1938 pp. 712–3

- ^ Downes 1938 p. 713

- ^ Moore 1920 pp.144-5

- ^ a b c Moore 1920 pp. 126–7

- ^ Powles 1922 p. 224

- ^ a b Hamilton 1996 p. 128

- ^ Powles 1922 p. 226

- ^ 2nd Light Horse Brigade War Diary AWM4, 10-2-42

- ^ Moore 1920 p. 127

- ^ Powles 1922 p. 225–6

- ^ Powles 1922 pp. 228–9

- ^ a b Hamilton 1996 p. 124

- ^ a b Australian Mounted Division War Diary AWM4, 1-58-12part1 June 1918

- ^ Hamilton 1996 p. 126

- ^ Hamilton 1996 p.125

- ^ Gullett 1919 p. 21

- ^ Lindsay 1992 p. 217

- ^ Hamilton 1996 pp. 127–8

- ^ Hamilton 1996 p. 129

- ^ Baly 2003 p. 227

- ^ Gullett 1941 pp. 674–5

- ^ Powles 1922 p. 230

- ^ G. Massey 2007 pp. 70–1

- ^ Gullett 1941 p. 644

- ^ Powles 1922 p. 231

- ^ 2nd Light Horse Brigade War Diary AWM4, 10-2-44

- ^ Hamilton 1996 p. 135

- ^ Hamilton 1996 p. 136

- ^ Hamilton 1996 p. 135–6

- ^ Mitchell 1978 pp. 160–1

- ^ Powles 1922 p. 223

References

- "2nd Light Horse Brigade War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 10-2-10 & 20. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. November 1915 & September 1916. http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/war_diaries/first_world_war/subclass.asp?levelID=1467.

- "4th Light Horse Brigade War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 10-4-17. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. May 1918. http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/records/awm4/subclass.asp?levelID=1465.

- "Australian Mounted Division General Staff War Diary". First World War Diaries AWM4, 1-58-12PART1. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. June 1918. http://www.awm.gov.au/collection/records/awm4/subclass.asp?levelID=1342.

- Handbook on Northern Palestine and Southern Syria, (1st provisional 9 April ed.). Cairo: Government Press. 1918. OCLC 23101324. [referred to as "Secret 9/4/18"]

- Baly, Lindsay (2003). Horseman, Pass By: The Australian Light Horse in World War I. East Roseville, Sydney: Simon & Schuster. OCLC 223425266.

- Blenkinsop, L.J. & J.W. Rainey, ed (1925). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents Veterinary Services. London: H.M. Stationers. OCLC 460717714.

- Bruce, Anthony (2002). The Last Crusade: The Palestine Campaign in the First World War. London: John Murray Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7195-5432-2.

- F. M. Cutlack (1941). "The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918". Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 Volume VIII. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/first_world_war/volume.asp?levelID=67894.

- R. M. Downes (1938). "The Campaign in Sinai and Palestine". Gallipoli, Palestine and New Guinea of Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914-1918 Part II in Volume 1. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. http://www.awm.gov.au/histories/first_world_war/volume.asp?levelID=67898.

- Falls, Cyril; A. F. Becke (maps) (1930). Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from June 1917 to the End of the War. Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. 2 Part II. London: HM Stationary Office. OCLC 256950972.

- Henry S. Gullett, Charles Barnet, Art Editor David Baker, ed (1919). Australia in Palestine. Sydney: Angus & Robertson Ltd. OCLC 224023558.

- Gullett, H.S. (1941). The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, 1914–1918. Official History of Australian in the War of 1914–1918, Volume VII. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 220900153.

- Hamilton, Patrick M. (1996). Riders of Destiny The 4th Australian Light Horse Field Ambulance 1917–18: An Autobiography and History. Gardenvale, Melbourne: Mostly Unsung Military History. ISBN 978-1-876179-01-4.

- Holloway, David (1990). Hooves, Wheels & Tracks a History of the 4th/19th Prince of Wales’ Light Horse Regiment and its predecessors. Fitzroy, Melbourne: Regimental Trustees. OCLC 24551943.

- Hughes, Matthew, ed (2004). Allenby in Palestine: The Middle East Correspondence of Field Marshal Viscount Allenby June 1917 – October 1919. Army Records Society. 22. Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7509-3841-9.

- Keogh, E. G.; Joan Graham (1955). Suez to Aleppo. Melbourne: Directorate of Military Training by Wilkie & Co.. OCLC 220029983.

- Lindsay, Neville (1992). Equal to the Task: The Royal Australian Army Service Corps, Volume 1. Kenmore: Historia Productions. OCLC 28994468.

- McPherson, Joseph W. (1985). Barry Carman, John McPherson. ed. The man who loved Egypt Bimbashi McPherson. London: Ariel Books BBC. ISBN 9780563204374.

- Massey, Graeme (2007). Beersheba: The men of the 4th Light Horse Regiment who charged on the 31st October 1917. Warracknabeal, Victoria: Warracknabeal Secondary College History Department. OCLC 225647074.

- Maunsell, E. B. (1926). Prince of Wales’ Own, the Seinde Horse, 1839-1922. OCLC 221077029.

- Mitchell, Elyne (1978). Light Horse The Story of Australia's Mounted Troops. Melbourne: Macmillan. OCLC 5288180.

- Moore, A. Briscoe (1920). The Mounted Riflemen in Sinai & Palestine The Story of New Zealand's Crusaders. Christchurch: Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd. OCLC 561949575.

- Preston, R. M. P. (1921). The Desert Mounted Corps: An Account of the Cavalry Operations in Palestine and Syria 1917–1918. London: Constable & Co.. OCLC 3900439.

- Powles, C. Guy; A. Wilkie (1922). The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine. Official History New Zealand's Effort in the Great War, Volume III. Auckland: Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd. OCLC 2959465.

- Scrymgeour, J. T. S. (1961?). Blue Eyes A True Romance of the Desert Column. Infracombe: Arthur H. Stockwell. OCLC 220903073.

- Wavell, Field Marshal Earl (1968). E.W. Sheppard. ed. The Palestine Campaigns. A Short History of the British Army (3rd ed.). London: Constable & Co..

- Woodward, David R. (2006). Hell in the Holy Land World War I in the Middle East. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2383-7.

Categories:- British occupations

- Military operations of World War I involving the United Kingdom

- Military operations of World War I involving Australia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.