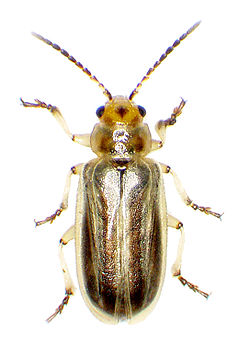

- Diorhabda carinulata

-

Diorhabda carinulata Northern Tamarisk Beetle

Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Order: Coleoptera Family: Chrysomelidae Subfamily: Galerucinae Genus: Diorhabda Species: D. carinulata Binomial name Diorhabda carinulata

Desbrochers, 1870Synonyms Diorhabda koltzei ab. basicornis Laboissière, 1935

Diorhabda elongata deserticola Chen, 1961

Diorhabda deserticola Chen, 1961Diorhabda carinulata is a species of leaf beetle known as the northern tamarisk beetle (NTB) which feeds on tamarisk trees from southern Russia and Iran to Mongolia and western China[1]. The NTB is used in North America as a biological pest control agent against saltcedar or tamarisk (Tamarix spp.), an invasive species in arid and semi-arid ecosystems (where the NTB and its closely related sibling species are also less accurately referred to as the 'saltcedar beetle', 'saltcedar leaf beetle', 'salt cedar leaf beetle', or 'tamarisk leaf beetle') (Tracy and Robbins 2009).

Contents

Taxonomy

The NTB was first described from southern Russia as Galeruca carinulata Desbrochers (1870). Weise (1893) created the genus Diorhabda and erroneously placed the NTB as a junior synonym of a sibling species, the Mediterranean tamarisk beetle, Diorhabda elongata (Brullé). Chen (1961) described the NTB in western China as a new subspecies Diorhabda elongata deserticola Chen. Yu et al. (1996) proposed the species D. deserticola. Berti and Rapillly (1973) recognized the NTB as a separate species Diorhabda carinulata (Desbrochers) based on detailed morphology of the endophallus of the male genitalia. Tracy and Robbins (2009) confirmed the findings of Berti and Rapilly (1973), established D. e. deserticola as a junior synonym to D. carinulata, and provided illustrated taxonomic keys separating the NTB from the four other sibling species of the D. elongata (Brullé) species group: Diorhabda elongata, Diorhabda carinata (Faldermann), Diorhabda sublineata (Lucas), and Diorhabda meridionalis Berti and Rapilly. In literature prior to 2009, D. carinulata was usually referred to as D. elongata, a China/Kazakhstan ecotype of D. elongata (in the U.S.), or D. elongata deserticola. (For additional information, see

Wikispecies: Diorhabda carinulata.)

Wikispecies: Diorhabda carinulata.)Host plants

Extensive literature on the biology and host range of the NTB in Kazakhstan, China, and Mongolia are found under the names of Diorhabda elongata and Diorhabda elongata deserticola[1]. The NTB is a well known pest of tamarisk in western China where in certain years large outbreaks of the beetle can defoliate thousands of acres of tamarisk trees. The NTB is controlled in western China to protect plantings of tamarisk for windbreaks and soil stabilization. In nature, the NTB feeds on at least 14 species of tamarisk and the closely related genus Myricaria, and all these food plants are restricted to the tamarisk plant family Tamaricaceae (Tracy and Robbins 2009). Extensive laboratory host range studies verified that NTB is a specialist feeder on tamarisks, feeding only on plants of the tamarisk family. In North America, NTB prefer T. ramosissima to T. parviflora in the field (Dudley et al. 2006) and this preference is also seen in laboratory studies (Dalin et al. 2009). In laboratory and field cage studies, the NTB will also feed and complete development on Frankenia shrubs of the family Frankeniaceae, distant relatives of tamarisks in the same plant order Tamaricales, but NTB greatly prefer to lay eggs upon tamarisk (DeLoach et al. 2003, Lewis et al. 2003a, Milbrath and DeLoach 2006). Field studies in Nevada confirm that the NTB will not significantly attack Frankenia (Dudley and Kazmer 2005).

Life cycle

The NTB overwinters as adults on the ground in leaf litter beneath tamarisk trees. Adults become active and begin feeding and mating in the early spring when tamarisk leaves are budding. Eggs are laid on tamarisk leaves and hatch in about a week in warm weather. Three larval stages feed on tamarisk leaves for about two and a half weeks when they crawl to the ground and spend about 5 days as a “C”-shaped inactive prepupa before pupating about one week. Adults emerge from pupae to complete the life cycle in about 4–5 weeks in the summer. (For images of various life stages, see

Wikimedia Commons: Diorhabda carinulata.) From two to four generations of tamarisk beetles occur through spring and fall in central Asia. In the late summer and early fall adults begin to enter diapause in which they cease reproduction and feed to build fat bodies before seeking a protected place to overwinter beneath the tamarisk (Lewis et al. 2003b). Larvae and adults are sensitive to shorter daylengths as the summer progresses that signal the coming of winter and induce diapause (Bean et al. 2007a, 2007b). Cossé et al. (2005) identified an aggregation pheromone that adult male NTB can emit to attract both males and females to certain tamarisk trees.

Wikimedia Commons: Diorhabda carinulata.) From two to four generations of tamarisk beetles occur through spring and fall in central Asia. In the late summer and early fall adults begin to enter diapause in which they cease reproduction and feed to build fat bodies before seeking a protected place to overwinter beneath the tamarisk (Lewis et al. 2003b). Larvae and adults are sensitive to shorter daylengths as the summer progresses that signal the coming of winter and induce diapause (Bean et al. 2007a, 2007b). Cossé et al. (2005) identified an aggregation pheromone that adult male NTB can emit to attract both males and females to certain tamarisk trees.Biological control agent

The NTB is currently the most successful biological control agent for tamarisk in North America. Populations of NTB from around 44°N latitude at Fukang, China and Chilik, Kazakhstan were initially released by the USDA Agricultural Research Service in 2001. Since its release, the NTB has defoliated tens of thousands of acres of tamarisk in Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming. However, the NTB appears to be poorly adapted to some areas where other species of Old World tamarisk beetles are being introduced, such as the Mediterranean tamarisk beetle, Diorhabda elongata, in northern California and parts of west Texas, and the larger tamarisk beetle, Diorhabda carinata (Faldermann), and the subtropical tamarisk beetle, Diorhabda sublineata (Lucas), in parts of west Texas (Tracy and Robbins 2009).

Tamarisk does not usually die from a single defoliation from tamarisk beetles, and it can resprout within several weeks of defoliation. Repeated defoliation of individual tamarisk trees can lead to severe dieback the next season and death of the tree within several years (DeLoach and Carruthers 2004). Tamarisk beetle defoliation over the course of at least one to several years can severely reduce the nonstructural carbohydrate reserves in the root crowns of tamarisk (Hudgeons et al. 2007). Biological control of tamarisk by the NTB will not eradicate tamarisk but it has the potential to suppress tamarisk populations by 75–85%, after which both NTB and tamarisk populations should reach equilibrium at lower levels (DeLoach and Carruthers 2004, Tracy and DeLoach 1999).

A primary objective of tamarisk biological control with the NTB is to reduce competition by exotic tamarisk with a variety of native riparian flora, including trees (willows, cottonwoods, and honey mesquite), shrubs (wolfberry, saltbush, and baccharis), and grasses (alkali sacaton, saltgrass, and creeping and basin wildryes). Unlike expensive chemical and mechanical controls of tamarisk that often must be repeated, tamarisk biological control does not harm native flora and is self-sustaining in the environment. Recovery of native riparian grasses can be quite rapid under the once closed canopy of repeatedly defoliated tamarisk. However, tamarisk beetle defoliation can locally reduce nesting habitat for riparian woodland birds until native woodland flora are able to return. In some areas, tamarisk may be replaced by grasslands or shrublands, resulting in losses of riparian forest habitats for birds (Tracy and DeLoach 1999). Releases of tamarisk beetles in southern California, Arizona, and along the Rio Grande in western New Mexico, are currently delayed until concerns can be resolved regarding safety of tamarisk biological control to nesting habitats of the federally endangered southwestern willow flycatcher, Empidonax traillii Audubon subspecies extimus Phillips, which will nest in tamarisk (see DeLoach et al. 2000, Dudley and DeLoach 2004). The NTB has defoliated some tamarisk nest trees of the southwestern willow flycatcher on the Virgin River in southern Utah, and actions to protect the flycatcher are under consideration[2]. In 2010, the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) officially discontinued its program for release of the NTB in 13 northwestern states (USDA APHIS 2005) over concern for the flycatcher (Gruver 2010). The Colorado Department of Agriculture is continuing to redistribute beetles within their state and they are seeing vigorous growth of native vegetation such as willows in response to reductions in tamarisk by the NTB (Johnson 2010).

References

- Bean, D.W.; Dudley, T.L.; Keller, J.C. 2007a: Seasonal timing of diapause limits the effective range of Diorhabda elongata deserticola (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) as a biological control agent for tamarisk (Tamarix spp.). Environmental Entomology, 36(1): 15–25. PDF

- Bean, D.W.; Wang, T.; Bartelt, R.J.; Zilkowski, B.W. 2007b: Diapause in the leaf beetle Diorhabda elongata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent for tamarisk (Tamarix spp.). Environmental Entomology, 36(3): 531–540. PDF

- Berti, N.; Rapilly, M. 1973: Contribution a la faune de l’Iran; Voyages de MM. R. Naviaux et M. Rapilly (Col. Chrysomelidae). Annales de la Société Entomologique de France, 9(4): 861–894. (In French)

- Chen, S.H. 1961: New Species of Chinese Chrysomelidae. Acta Entomologica Sinica, 10(4–6): 429–435. (In Chinese with English summary)

- Cossé, A.A.; Bartelt, R.J.; Zilkowski, B.W.; Bean, D.W.; Petroski, R.J. 2005: The aggregation pheromone of Diorhabda elongata, a biological control agent of saltcedar (Tamarix sp.): Identification of two behaviorally active components. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 31(3): 657–670. PDF

- Dalin, P.; O'Neal, M.J.; Dudley, T.; Bean, D.W.; 2009: Host plant quality of Tamarix ramosissima and T. parviflora for three sibling species of the biocontrol insect Diorhabda elongata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Environmental Entomology, 38(5): 1373–1378. PDF

- DeLoach, C.J.; Lewis, P.A.; Herr, J.C.; Carruthers, R.I.; Tracy, J.L.; Johnson, J. 2003: Host specificity of the leaf beetle, Diorhabda elongata deserticola (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) from Asia, a biological control agent for saltcedars (Tamarix: Tamaricaceae) in the western United States. Biological Control, 27: 117–147. PDF

- DeLoach, C.J.; Carruthers, R. 2004: Biological control programs for integrated invasive plant management. In: Proceedings of Weed Science Society of America Meeting, Kansas City, MO. Weed Science Society of America (CD-ROM). 17 pp. PDF

- DeLoach, C.J.; Carruthers, R.I.; Lovich, J.E.; Dudley, T.L.; Smith, S.D. 2000: Ecological interactions in the biological control of saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) in the United States: toward a new understanding. In: N. R. Spencer (ed.), Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds, 4–14 July 1999, Montana State University. Bozeman, Montana, pp. 819–873. PDF

- Desbrochers des Loges, M.J. 1870: Descriptions de Coléoptères nouveaux d’Europe et confins. L’Abeille, Volume 7, Part 1: 10–135. (In French)

- Dudley, T.L. DeLoach, C.J. 2004: Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.), endangered species, and biological weed control-can they mix? Weed Technology, 18(5): 1542–1551. PDF

- Dudley, T.L.; Kazmer, D.J. 2005: Field assessment of the risk posed by Diorhabda elongata, a biocontrol agent for control of saltcedar (Tamarix spp.), to a nontarget plant, Frankenia salina. Biological Control, 35: 265–275. PDF

- Dudley, T. L.; Dalin, P.; Bean, D.W 2006: Status of biological control of Tamarix spp. in California. In: M. S. Hoddle and M. W. Johnson (eds.), Proceedings of the Fifth California Conference on Biological Control, 25–26 July 2006, Riverside, CA. University of California at Riverside, Riverside, California, pp. 137–140. PDF

- Gruver, M. 2010: USDA stops using beetles vs. invasive saltcedar. Associated Press, 21 June 2010. [1]

- Hudgeons, J.L.; Knutson, A.E.; Heinz, K.M.; DeLoach, C.J.; Dudley, T.L.; Pattison, R.R.; Kiniry, J.R. 2007: Defoliation by introduced Diorhabda elongata leaf beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) reduces carbohydrate reserves and regrowth of Tamarix (Tamaricaceae). Biological Control, 43: 213–221. PDF

- Johnson, K. 2010: In battle of bug vs. shrub, score one for the bird. New York Times, 22 June 2010. [2]

- Lewis, P.A.; DeLoach, C.J; Herr, J.C.; Dudley, T.L.; Carruthers, R.I. 2003a: Assessment of risk to native Frankenia shrubs from an Asian leaf beetle, Diorhabda elongata deserticola (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), introduced for biological control of saltcedars (Tamarix spp.) in the western United States. Biological Control, 27: 148–166. PDF

- Lewis, P.A.; DeLoach, C.J.; Knutson, A.E.; Tracy, J.L.; Robbins, T.O. 2003b: Biology of Diorhabda elongata deserticola (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), an Asian leaf beetle for biological control of saltcedars (Tamarix spp.) in the United States. Biological Control, 27: 101–116. PDF

- Milbrath, L.; DeLoach, C.J. 2006: Host specificity of different populations of the leaf beetle Diorhabda elongata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a biological control agent of saltcedar (Tamarix spp.). Biological Control, 36: 32–48. PDF

- Tracy, J.L.; DeLoach, C.J. 1999: Biological control of saltcedar in the United States: Progress and projected ecological effects. In: Bell, C.E. (Ed.), Arundo and Saltcedar: The Deadly Duo, Proceedings of the Arundo and Saltcedar Workshop, 17 June 1998. Ontario, California, 111–154. PDF

- Tracy, J.L.; Robbins, T.O. 2009: Taxonomic revision and biogeography of the Tamarix-feeding Diorhabda elongata (Brullé, 1832) species group (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Galerucinae: Galerucini) and analysis of their potential in biological control of Tamarisk. Zootaxa, 2101: 1-152. PDF

- Yu, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, X. 1996: Economic Insect Fauna of China, Fasc. 54, Coleoptera: Chrysomeloidea (II). Science Press, Beijing, China, 324 pp. (In Chinese)

- Weise, J. 1893: Chrysomelidae. In: Erichson, W. (ED.), Naturgeschichte der Insecten Deutchland, 61(73): 961–1161. (In German)

- USDA APHIS. 2005: Program for Biological Control of Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) in Thirteen States: Environmental Assessment. USDA APHIS, Fort Collins, Colorado. 56 pp. PDF

Notes

- ^ a b Tracy and Robbins (2009) provide a detailed review of the distribution, biogeography, biology, and taxonomy of D. carinulata that is a general source for most of this article.

- ^ See link to Center for Biological Diversity 17 June 2009 press release below.

External links

- Center for Biological Diversity 17 June 2009 press release regarding lawsuit to protect the southwestern willow flycatcher in view of defoliation of tamarisk nesting habitat by D. carinulata. [3]

- Montana War on Weeds information on D. carinulata (not D. elongata) for tamarisk biocontrol. [4]

- Tamarisk Coalition information on tamarisk biocontrol (China and Kazakhstan source tamarisk beetles are D. carinulata).[5]

- University of California Berkeley Campus News article on initial 2001 release of D. carinulata (not D. elongata). [6]

- USDA/ARS research with D. carinulata (not D. elongata) for tamarisk biocontrol in Wyoming and Montana. [7]

- USDA/ARS and Texas Agri-Life Research and Extension Service Report of Information to the Public; Progress on Biological Control of Saltcedar in the Western U.S.: Emphasis—Texas 2004-2009. PDF

Categories:- Chrysomelidae

- Biological pest control agents

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.