- Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior

-

Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior

Commodore 64 box art, featuring Michael Van Wijk and Maria WhittakerDeveloper(s) Palace Software Publisher(s) Palace Software (Europe), Epyx (North America) Platform(s) Acorn Electron, Amiga, Amstrad CPC, Apple II, Atari ST, BBC Micro, Commodore 64, MS-DOS, ZX Spectrum Release date(s) 1987 Genre(s) Fighting game Mode(s) Single-player, and two-player versus Media/distribution Floppy disk, compact audio cassette Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior is a video game first released for Commodore 64 personal computers in 1987; the title was developed and published by Palace Software, and ported to other computers in the following months. The developers licensed the game to Epyx, who published it as Death Sword in the United States. Barbarian is a fighting game that gives players control over sword-wielding barbarians. In the game's two-player mode, players pit their characters against each other. Barbarian also has a single-player mode, in which the player's barbarian braves a series of challenges set by an evil wizard to rescue a princess.

Instead of using painted artwork for the game's box, Palace Software used photos of hired models. The photos, also used in advertising campaigns, featured bikini-clad Maria Whittaker, a model who was then associated with The Sun tabloid's Page Three topless photo shoots. Palace Software's marketing strategy provoked outrage in the United Kingdom; protestors focused on sexual aspects of the packaging rather than decapitations and other violence within the game. The ensuing controversy boosted Barbarian's profile, helping to make it a commercial success. Game critics were impressed with its fast and furious combat, and dashes of humour. The game was Palace Software's critical hit; boosted by Barbarian's success, Palace Software expanded its operations, publishing other developers' work. In 1988, the company released a sequel, Barbarian II: The Dungeon of Drax.

Contents

Gameplay

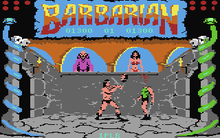

Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior is a fighting game that supports one or two players. Players assume the roles of sword-wielding barbarians, who battle in locales such as a forest glade and a "fighting pit".[1] The game's head-to-head mode lets a player fight against another or the computer in time-limited matches. The game also features a single-player story mode, which comprises a series of plot-connected challenges.[2]

Using joysticks or the keyboard, players move their characters around the arena, jumping to dodge low blows and rolling to dodge or trip the opponent. By holding down the fire button and moving the controller, players directs their barbarian to kick, headbutt, or attack with his sword.[3][4] Each barbarian has 12 life points, which are represented as 6 circles in the top corners of the interface. A successful attack on a barbarian takes away one of his life points (half a circle). The character dies when his life points are reduced to zero. Alternatively, a well-timed blow to the neck decapitates the barbarian, killing him instantly. A goblin enters the arena, kicks the head, and drags the body away.[5]

If the players do not input any commands for a time, the game attempts a self-referencing action to draw their attentions: the barbarians turn to face the players, shrug their shoulders, and say "C'mon".[6][7] The game awards points for successful attacks; the more complex the move, the higher the score awarded.[4] A score board displays the highest points achieved for the game.[1]

Single-player story mode

In the single-player story mode, the player controls a nameless barbarian who is on a quest to defeat the evil wizard Drax. Princess Mariana has been kidnapped by Drax, who is protected by 8 barbarian warriors. The protagonist engages each of the other barbarians in single combat to the death.[3][8] Overcoming them, he faces the wizard. After the barbarian has killed Drax, Mariana drops herself at her saviour's feet and the screen fades to black.[9] The United States version of the game names the protagonist Gorth.[10]

Development

In 1985, Palace Software hired Steve Brown as a game designer and artist. He thought up the concept of pitting a broom-flying witch against a monster pumpkin, and created Cauldron and Cauldron II: The Pumpkin Strikes Back. The two games were commercial successes and Brown was given free rein for his third work. He was inspired by Frank Frazetta's fantasy paintings to create a sword fighting game that was "brutal and as realistic as possible".[11] Brown based the game and its characters on the Conan the Barbarian series, having read all of Robert E Howard's stories of the titular warrior.[12] He conceptualised 16 moves and practiced them with wooden swords, filming his sessions as references for the game's animation. One move, the Web of Death, was copied from the 1984 sword and sorcery film Conan the Destroyer. Spinning the sword like a propeller, Brown "nearly took [his] eye out" when he practiced the move.[6][11] Playing back the videos, the team traced each frame of action onto clear plastic sheets laid over the television screen. The tracings were transferred on a grid that helped the team map the swordplay images, pixel by pixel, to a digital form.[13]

Feeling that most of the artwork on game boxes at that time were "pretty poor", Brown suggested that an "iconic fantasy imagery with real people would be a great hook for the publicity campaign."[11] His superiors agreed and arranged a photo shoot, hiring models Michael Van Wijk and Maria Whittaker to pose as the barbarian and princess.[14] Whittaker was a topless model, who frequently appeared on Page Three of the tabloid, The Sun. She wore a tiny bikini for the shoot while Van Wijk, wearing only a loincloth, posed with a sword.[11] Palace Software also packaged a poster of Whittaker in costume with the game.[3] Just before release, Palace Software discovered that fellow developer Psygnosis was producing a game also titled Barbarian, albeit of the platform genre. After several discussions, Palace Software appended the subtitle "The Ultimate Warrior" to differentiate the two products.[15]

Releases

Barbarian was released in 1987 for the Commodore 64 and in the months that followed, most other home computers.[11] These machines were varied in their capabilities, and the software ported to them was modified accordingly. The version for the 8-bit ZX Spectrums was mostly monochromatic; it displayed the outlines of the barbarians against single-colour backgrounds. The sounds were reproduced with a lower sampling rate.[16] Conversely, the Atari ST version, which had 16- and 32-bit buses, presents a greater variety of backgrounds and slightly higher quality graphics than the original version. Its story mode also pits 10 barbarians against the player instead of the usual 8.[2] Digitised sound samples are used in the Atari ST and 32-bit Amiga versions;[17][18] the latter also features digitised speech. Each fight begins with the announcement of "Prepare to die!", and metallic sounding thuds and clangs ring out as swords clash against each other.[6] After the initial releases, Barbarian was re-released several times; budget label Kixx published these versions without Whittaker on the covers.[19] Across the Atlantic, video game publisher Epyx acquired the license to Barbarian, releasing it under the title Death Sword, as part of their "Maxx Out!" video game series.[20]

Reception and legacy

During the 1980s, the prevalent attitude was that video games were for children. Barbarian's advertisements, showing a scantily dressed model known for topless poses, triggered significant outcries of moral indignity. Electron User magazine received letters from readers and religious bodies, who called the image "offensive and particularly insulting to women" and an "ugly pornographic advertisement".[11] Chris Jager, a writer for PC World, considered the cover "a trashy controversy-magnet featuring a glamour-saucepot" and a "big bloke [in leotard]".[21] According to Palace Software's co-founder Richard Leinfellner, the controversy did not negatively affect Barbarian, but boosted the game's sales and profile tremendously.[11] Video game industry observers Russell DeMaria and Johnny Wilson commented that the United Kingdom public were more concerned over scantily clad Whittaker than the gory contents in the game.[22] Conversely, Barbarian was banned in Germany by the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien for its violent contents.[7] The ban forbade promotion of the game and its sale to customers under the age of 18.[23] Barbarian's mix of sex and violence was such that David Houghton, writer for GamesRadar, said the game would be rated "Mature" if it was published in 2009.[24]

Reviewers were impressed with Barbarian's gory gameplay. Zzap!64's Steve Jarratt appreciated the "fast and furious" action and his colleague Ciaran Brennan said Barbarian should have been the licensed video game to the fantasy action film Highlander (which had a lot of swordfights and decapitations) instead.[3] Amiga Computing's Brian Chappell enjoyed "hacking the foe to bits, especially when a well aimed blow decapitates him."[18] Several other reviewers express the same satisfaction in lopping the heads off their foes.[2][18] Although shocked at the game's violence, Antic's reviewer said the "sword fight game is the best available on the ST."[25] According to Jarratt, Barbarian represented "new heights in bloodsports".[3] Equally pleasing to the reviewers at Zzap!64 and Amiga User International's Tony Horgan was the simplicity of the game; they found that almost anyone could quickly familiarise themselves with the game mechanics, making the two-player mode a fun and quick pastime.[3][26]

Although the barbarian characters use the same basic blocky sprites, they impressed reviewers at Zzap!64 and Amiga Computing with their smooth animation and life-like movements.[18][27] Reviewers of the Amiga version, however, expressed disappointment with the port for failing to exploit the computer's greater graphics capability and implement more detailed character sprites.[1][26] Its digitised sounds, however, won praise from Commodore User's Gary Penn.[6] Advanced Computer Entertainment's reviewers had similar thoughts over the Atari ST port.[28]

In his review for Computer and Video Games, Paul Boughton was impressed by the game's detailed gory effects, such as the aftermath of a decapitation, calling them "hypnotically gruesome".[13] It was these little touches that "[makes] the game worthwhile", according to Richard Eddy in Crash.[13][29] Watching "the head [fall] to the ground [as blood spurts from the] severed neck, accompanied by a scream and satisfying thud as the torso tumbles" proved to be "wholesome stuff" for Chappell.[18] The scene was a "great retro gaming moment" for Retro Gamer's staff.[30] The cackling goblin, which drags off the bodies, endeared him to some reviewers;[1][29] the team at Retro Gamer regretted that the creature did not have his own game.[11] The actions of the barbarian also impressed them to nominate him as one of their top 50 characters from the early three decades of video gaming.[31]

Barbarian proved to be a big hit, and Palace started planning to publish a line of sequels. Barbarian II: The Dungeon of Drax was released in 1988, and Barbarian III was in the works.[11] Van Wijk and Whittaker were hired again to grace the box cover and advertisements.[32] After the success with Barbarian, Palace Software began to expand its portfolio by publishing games that were created by other developers. Barbarian, however, remained its most popular game, best remembered for its violent swordfights and Maria Whittaker.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d Jenkins, Chris (May 1988). "Reviews—Barbarian". Computer and Video Games (London, United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing) (79): pp. 58–59. ISSN 0261-3697.

- ^ a b c Wild, Nik; Hogg, Robin; Eddy, Richard; Rothwell, Mark; Candy, Robin (December 1987 – January 1988). "Ice-crisp Sword Clash". The Games Machine (Shropshire, United Kingdom: Newsfield Publications) (2): p. 47. ISSN 0954-8092.

- ^ a b c d e f Rignall, Julian; Brennan, Ciaran; Jarratt, Steve (July 1987). "Test—Barbarian". Zzap!64 (Shropshire, United Kingdom: Newsfield Publications) (27): pp. 88–89. ISSN 0954-867X.

- ^ a b Boughton, Paul (June 1987). "Birth of the Barbarian". Computer and Video Games (London, United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing) (68): pp. 14–15. ISSN 0261-3697.

- ^ Jones, Darran (2 March 2006). "RetroRevival—Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth, United Kingdom: Imagine Publishing) (22): p. 44. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ a b c d Penn, Gary (April 1988). "Barbarian". Commodore User (London, United Kingdom: EMAP): p. 74. ISSN 0265-721X.

- ^ a b Rapp, Bernhard (2007). "Self-reflexitivity in computer games: Analyses of selected examples". In Nöth, Winfried; Bishara, Nina. Self-reference in the Media. Approaches to Applied Semiotics. 6. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 259, 262. ISBN 3-11019-464-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=NBOFIdchEQYC&pg=PA253. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ Shaw, Pete (July 1987). "Screen Shots". Your Sinclair (London, United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing) (19): p. 30. ISSN 0269-6983.

- ^ Vaughan, Craig (31 August 2004). "Over the Rainbow". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth, United Kingdom: Imagine Publishing) (7): p. 37. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ "Introduction". Death Sword. Maxx Out!. California, United States: Epyx. 1988. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Carroll, Martyn (30 March 2006). "Company Profile: Palace Software". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth, United Kingdom: Imagine Publishing) (23): pp. 66–69. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ Amstrad Cent Pour Cent staff (July / August 1988). "Et Steve Brown créa Barbarian [And Steve Brown created Barbarian]" (in French). Amstrad Cent Pour Cent (Paris, France: Media Publishing System): pp. 6–7. ISSN 0988-8160.

- ^ a b c Boughton, Paul (June 1987). "Birth of the Barbarian". Computer and Video Games (London, United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing) (68): pp. 42–43. ISSN 0261-3697.

- ^ Your Sinclair staff (June 1987). "Frontlines". Your Sinclair (London, United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing) (18): p. 5. ISSN 0269-6983.

- ^ Computer Gamer staff (June 1987). "Gamer News". Computer Gamer (London, United Kingdom: Argus Press) (68): p. 8. ISSN 0744-6667.

- ^ Stone, Ben; Eddy, Richard; Sumner, Paul (June 1987). "Barbarian". Crash (Ludlow, United Kingdom: Newsfield Publications) (41): pp. 114–115. ISSN 0954-8661.

- ^ ACE staff (November 1987). "Screen Test Updates". Advanced Computer Entertainment (Bath, United Kingdom: Future Publishing) (2): p. 75.

- ^ a b c d e Chappell, Brian (July 1988). "Barbarian". Amiga Computing (United Kingdom: Europress Impact) 1 (2): p. 44. ISSN 0952-5948.

- ^ Campbell, Stuart (August 1991). "Game Reviews—Budget Titles". Amiga Power (Bath, United Kingdom: Future Publishing) (4): p. 80. ISSN 0961-7310.

- ^ Computer Gaming World staff (July 1988). "Taking a Peep". Computer Gaming World (California, United States: Golden Empire Publications) (49): p. 7. ISSN 0744-6667.

- ^ Jager, Chris (2009-02-28). "The Hottest—and Most Hideous—Video Game Box Art Ever". PC World. IDG. http://www.pcworld.com/article/160321/the_hottest_and_most_hideous_video_game_box_art_ever.html. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ^ DeMaria, Russell; Wilson, Johnny (2004). "Across the Atlantic". High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games. Electronic Games (Second ed.). California, United States: McGraw-Hill/Osborne. p. 356. ISBN 0-07223-172-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=HJNvZLvpCEQC&pg=PA320. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ^ Sinclair User staff (November 1987). "Whodunwot". Sinclair User (London, United Kingdom: EMAP) (68): pp. 8–9. ISSN 0262-5458.

- ^ Houghton, David (2009-12-14). "Games You Played as a Kid that would be Mature Rated Today". GamesRadar (United Kingdom). Future Publishing. http://www.gamesradar.com/f/games-you-played-as-a-kid-that-would-be-mature-rated-today/a-2009121414954520080. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ^ Manor, John; Plotkin, David; Panak, Steve (December 1988). "ST Games Gallery: Speed Buggy, Death Sword, Global Commander, and More". Antic (California, United States: Antic Publishing) 7 (8): p. 53. ISSN 0113-1141. http://www.atarimagazines.com/v7n8/stgamegallery.html. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ^ a b Horgan, Tony (June 1988). "Barbarian". Amiga User International (United Kingdom: Croftward) 2 (6): pp. 42–43. ISSN 0955-1077.

- ^ Zzap!64 staff (January 1990). "Test—Barbarian". Zzap!64 (Shropshire, United Kingdom: Newsfield Publications) (57): p. 49. ISSN 0954-867X.

- ^ ACE staff (November 1987). "Screen Test Updates". Advanced Computer Entertainment (Bath, United Kingdom: Future Publishing) (2): p. 75.

- ^ a b Eddy, Richard; Candy, Robin (October 1987). "Kick High". Crash (Ludlow, United Kingdom: Newsfield Publications) (45): pp. 38–39. ISSN 0954-8661.

- ^ Retro Gamer staff (2006). "Great Retro Gaming Moments: Barbarian". Retro. 2. Bournemouth, United Kingdom: Imagine Publishing. p. 169. ISBN 0-95530-323-0.

- ^ Retro Gamer staff (April 2004). "The Top 50 Retro Game Characters". Retro Gamer (Bournemouth, United Kingdom: Imagine Publishing) (2): p. 37. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ Boughton, Paul (May 1988). "The Axe Man Cometh". Computer and Video Games (London, United Kingdom: Dennis Publishing) (81): pp. 100–101. ISSN 0261-3697.

Categories:- 1987 video games

- Amiga games

- Amstrad CPC games

- Apple II games

- Atari ST games

- BBC Micro and Acorn Electron games

- Commodore 64 games

- DOS games

- Epyx games

- Fighting games

- Multiplayer video games

- Versus fighting games

- Video games developed in the United Kingdom

- ZX Spectrum games

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.