- Construct (philosophy of science)

-

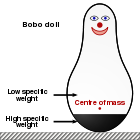

An object's center of mass is certainly a real thing, but it is a construct (not another object)

An object's center of mass is certainly a real thing, but it is a construct (not another object)

A construct in the philosophy of science is an ideal object, where the existence of the thing may be said to depend upon a subject's mind. This, as opposed to a "real" object, where existence does not seem to depend on the existence of a mind.[1]

In a scientific theory, particularly within psychology, a hypothetical construct is an explanatory variable which is not directly observable. For example, the concepts of intelligence and motivation are used to explain phenomena in psychology, but neither is directly observable. A hypothetical construct differs from an intervening variable in that it has properties and implications which have not been demonstrated in empirical research. These serve as a guide to further research. An intervening variable, on the other hand, is a summary of observed empirical findings.

The creation of constructs is a part of Operationalization, especially the creation of Theoretical definitions. The usefulness of one conceptualization over another depends largely on construct validity.

Contents

Construct versus object

Concepts that are considered constructs by this definition include that which is designated by the symbol "3" or the word "liberty". Scientific hypotheses and theories (e.g., evolutionary theory, gravitational theory), as well as classifications (e.g. in biological taxonomy) are also conceptual entities considered to be constructs.

Some simple examples of real objects (that are not constructs) are lawyers and undershirts.

History

Cronbach and Meehl (1948) define a hypothetical construct as a concept for which there is not a single observable referent, which cannot be directly observed, and for which there exist multiple referents, but none all-inclusive. For example, according to Cronbach and Meehl a fish is not a hypothetical construct because, despite variation in species and varieties of fish, there is an agreed upon definition for a fish with specific characteristics that distinguish a fish from a bird. Furthermore, a fish can be directly observed. On the other hand a hypothetical construct has no single referent; rather, hypothetical constructs consist of groups of functionally related behaviors, attitudes, processes, and experiences. Instead of seeing intelligence, love, or fear we see indicators or manifestations of what we have agreed to call intelligence, love, or fear. Other examples of hypothetical constructs include gravity, creativity, menopause, and guilt.

McCorquodale and Meehl (1948) discussed the distinction between what they called intervening variables and these hypothetical constructs. According to McCorquodale and Meehl (1948) intervening variables are defined solely in terms of their antecedents and consequences. Thus, intervening variables are operationally defined congruent with the philosophy of Positivism that was popular at the time. In contrast, McCorquodale and Meehl (1948) describe hypothetical constructs as containing surplus meaning, as they imply more than just the operations by which they are measured.

In the positivist tradition, Boring (1923) described intelligence as whatever the intelligence test measures. As a reaction to such operational definitions, Cronbach and Meehl (1955) emphasized the necessity of viewing constructs like intelligence as hypothetical constructs. They asserted that there is no adequate criterion for the operational definition of constructs like abilities and personality. Thus, according to Cronbach and Meehl (1955), a useful construct of intelligence or personality should imply more than simply test scores. Instead these constructs should predict a wide range of behaviors.

Sources

Boring, E.G. (1923) Intelligence as the tests test it. New Republic, 36, 35-37.

Cronbach, L.J., and Meehl, P.E. (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281-302.

MacCorquodale, K.,& Meehl, P.E. (1948). On a distinction between hypothetical constructs and intervening variables. Psychological Review, 55, 95-107.

References

- ^ Bunge, M. 1974. Treatise on Basic Philosophy, Vol. I Semantics I: Sense and Reference. Dordrecth-Boston: Reidel Publishing Co.

Categories:- Science stubs

- Scientific method

- Philosophical concepts

- Philosophy of science

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.