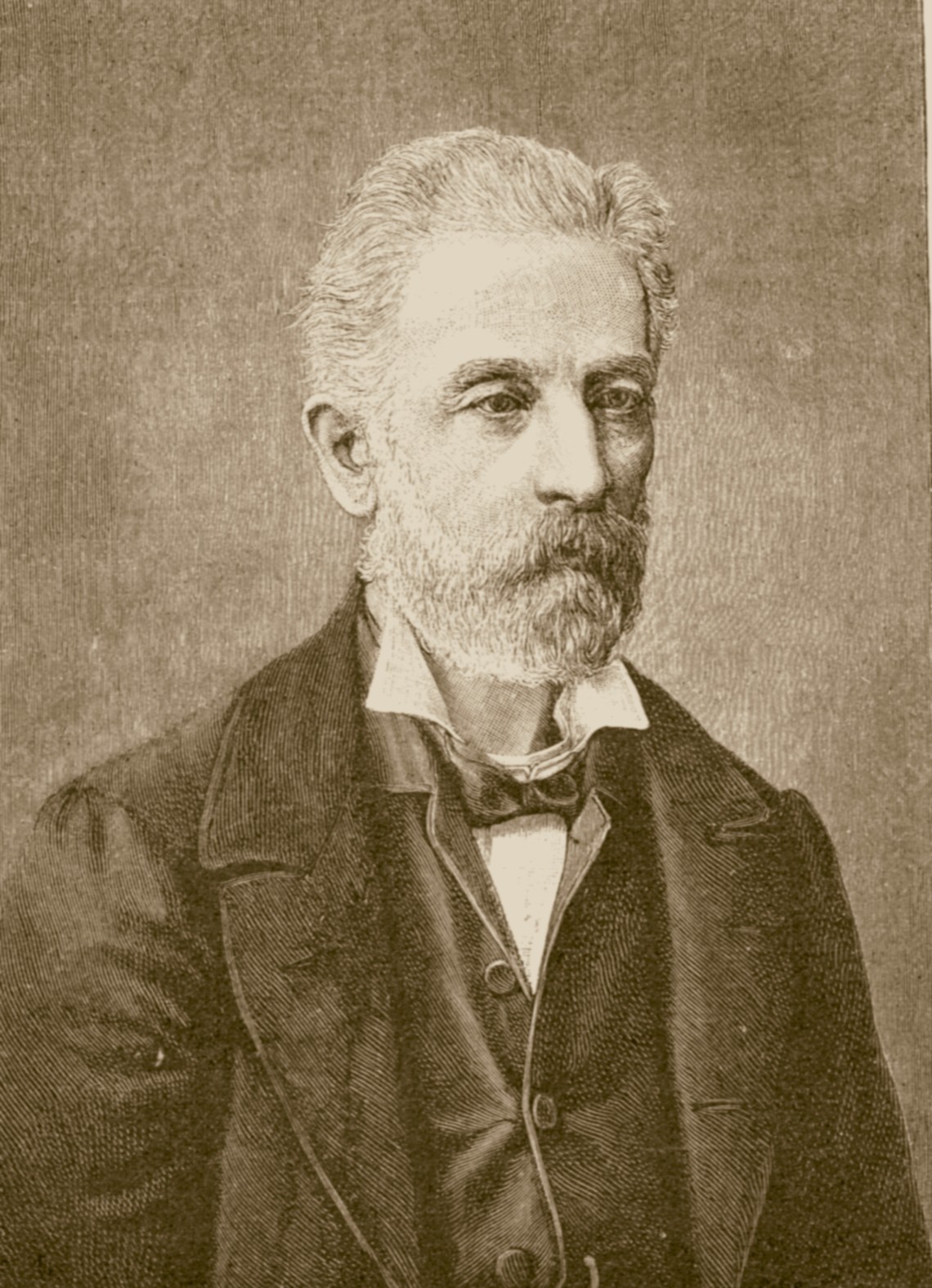

- Adolf Bastian

Infobox Scientist

name = Adolf Bastian

box_width =

image_width =150px

caption = Adolf Bastian

birth_date =26 June 1826

birth_place =Bremen ,Germany

death_date =2 February 1905

death_place =Port of Spain ,Trinidad and Tobago

residence =

citizenship =

nationality =

ethnicity =

field =anthropology

work_institutions =

alma_mater =

doctoral_advisor =

doctoral_students =

known_for =

author_abbrev_bot =

author_abbrev_zoo =

influences =

influenced =

prizes =

religion =

footnotes =

Adolf Bastian (26 June 1826 –2 February 1905 ) was a 19th centurypolymath best remembered for his contributions to the development ofethnography and the development ofanthropology as a discipline. Modern psychology owes him a great debt, because of his theory of the "Elementargedanke", which led toCarl Jung 's development of the theory of "archetypes". [Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology, p. 32. London: Secker & Warburg: 1960. "Jung's idea of the "archetypes" is one of the leading theories, today, in the field of our subject. It is a development of the earlier theory of Adolf Bastian..."]Bastian was born in Bremen,

German Confederation , into a prosperousbourgeois German family of merchants. His career at university was broad almost to the point of being eccentric. He studied law at theRuprecht Karl University of Heidelberg , andbiology at what is todayHumboldt University of Berlin , theFriedrich Schiller University of Jena , and theUniversity of Würzburg . It was at this last university that he attended lectures byRudolf Virchow and developed an interest in what was then known as 'ethnology'. He finally settled on medicine and earned a degree fromPrague in 1850.Bastian became a ship's doctor and began an eight year voyage which took him around the world. This was the first of what would be a quarter of a century of travels outside the German Confederation. He returned to the Confederation in 1859 and wrote a popular account of his travels along with an ambitious three volume work entitled "Man in History", which became one of his most well-known works.

In 1861 he undertook a four-year trip to

Southeast Asia and his account of this trip, "The People of East Asia" ran to six volumes. For the next eight years Bastian remained in the territory of theNorth German Confederation , where be became involved in the creation of several key ethnological institutions in Berlin. He had always been an avid collector, and his contributions to Berlin's Royal museum was so copious that a second museum, theMuseum of Folkart , was founded largely as a result of Bastian's contributions. Its collection of ethnographic artifacts became one of the largest in the world for decades to come. He also worked withRudolf Virchow to organize theEthnological Society of Berlin . During this period he was also the head of theRoyal Geographical Society of Germany . Among others who worked under him at the museum was the youngFranz Boas who later founded the American school of ethnology.In the 1870s Bastian left the

German Empire and began travelling extensively inAfrica as well as theNew World .He died in

Port of Spain ,Trinidad and Tobago during one these journeys in 1905.Works and ideas

Bastian is remembered as one of the pioneers of the concept of the 'psychic unity of mankind' -- the idea that all humans share a basic mental framework. This became the basis in other guises of 20th century

structuralism , and influencedCarl Jung 's idea of thecollective unconscious . He also argued that the world was divided up into different 'geographical provinces' and that each of these provinces moved through the same stages of evolutionary development. According to Bastian, innovations and culture traits tended not to diffuse across areas. Rather, each province took its unique form as a result of its environment. This approach was part of a larger nineteenth century interest in the 'comparative method' as practiced by anthropologists such asEdward B. Tylor .While Bastian considered himself to be extremely scientific, it is worth noting that he emerged out of the naturalist tradition that was inspired by

Johann Gottfried Herder and exemplified by figures such asAlexander von Humboldt . For him,empiricism meant a rejection of philosophy in favor of scrupulous observations. As a result, he was extremely hostile to Darwin's theory ofevolution because the physical transformation of species had never been empirically observed, despite the fact that he posited a similar evolutionary development for human civilization. Additionally, he was much more concerned with documenting unusual civilizations before they vanished (presumably as a result of contact with Western civilization) than with the rigorous application of scientific observation. As a result, some have criticized his works for being disorganized collections of facts rather than coherently structured or carefully researched empirical studies.Fact|date=March 2008The Psychic Unity of Mankind in Greater Detail

In arguing for the “psychic unity of mankind,” Bastian proposed a straightforward project for the long-term development of a science of human culture and consciousness based upon this notion. He argued that the mental acts of all people everywhere on the planet are the products of physiological mechanisms characteristic of the human species (what today we might term the genetic loading on the organization and functioning of the human neuroendocrine system). Every human mind inherits a complement of species-specific “elementary ideas” ("Elementargedanken"), and hence the minds of all people, regardless of their race or culture, operate in the same way.

According to Bastian, the contingencies of geographic location and historical background create different local elaborations of the "elementary ideas"; these he called "folk ideas" ("Volkergedanken"). Bastian also proposed a lawful “genetic principle” by which societies develop over the course of their history from exhibiting simple sociocultural institutions to becoming increasingly complex in their organization. Through the accumulation of ethnographic data, we can study the psychological laws of mental development as they reveal themselves in diverse regions and under differing conditions. Although one is speaking with individual informants, Bastian held that the object of research is not the study of the individual per se, but rather the “folk ideas” or “collective mind” of a particular people.

The more one studies various peoples, Bastian thought, the more one sees that the historically conditioned "folk ideas" are of secondary importance compared with the universal "elementary ideas". The individual is like the cell in an organism, a social animal whose mind - its "folk ideas" - is influenced by its social background; and the "elementary ideas" are the ground from which these “folk ideas” develop. From this perspective, the social group has a kind of group mind, a social “soul” ("Gesellschaftsseele") if you will, in which the individual mind is embedded.

Bastian believed that the "elementary ideas" are to be scientifically reconstructed from "folk ideas" as varying forms of collective representations ("Gesellschaftsgedanken"). Because one cannot observe the collective representations per se, Bastian felt that the ethnographic project had to proceed through a series of five analytical steps (see Koepping, 1983):

* 1. Fieldwork: Empirical description of cross-cultural data (as opposed to armchair philosophy; Bastian himself spent much of his adult life among non-European peoples).

* 2. Deduction of collective representations: From cross-cultural data we describe the collective representations in a given society.

* 3. Analysis of folk ideas: Collective representations are broken down into constituent folk ideas. Geographical regions often exhibit similar patterns of folk ideas – he called these “idea circles” which described the collective representations of particular regions.

* 4. Deduction of elementary ideas: Resemblances between folk ideas and patterns of folk ideas across regions indicate underlying elementary ideas.

* 5. Application of a scientific psychology: Study of elementary ideas defines the psychic unity of mankind, which is due to the underlying psychophysiological structure of the species – this study is to be accomplished by a truly scientific, cross-culturally grounded psychology.What Bastian argued for was nothing less than what today we might call a psychobiologically grounded, cross-cultural social psychology. The key to developing this robust science of human consciousness was to collect as much ethnographic data as possible from all over the world before folk cultures became too “tainted” by contact with European imperialist powers. Through ethnographic research, he wrote, we can study the psychological laws of mental development as they reveal themselves in diverse geographical settings. Thus in modern day parlance, our different sociocultural forms are due both to trans-culturally shared (i.e.,

archetypal ) processes inherent in our very distinct human psychophysiology -- much of it operating at a non-conscious level -- and to our development (orenculturation ) within a particular environment.References and notes

Sources and further reading

Buchheit, Klaus Peter: "Die Verkettung der Dinge. Stil und Diagnose im Schreiben Adolf Bastians" ("Concatenation of things : Style and Diagnosis as methods of Adolf Bastian's writing and of writing Adolf Bastian"), Lit Verlag Münster 2005

Buchheit, Klaus Peter; Klaus Peter Koepping: "Adolf Philipp Wilhelm Bastian", in: Feest/Kohl (Hg.) "Hauptwerke der Ethnologie", Kröner Stuttgart 2001:19-25

Buchheit, Klaus Peter: "The Concatenation of Minds" (an essay on Bastian's conception of lore), in: Rao/Hutnyk (Hg.) "Celebrating Transgression. Method and Politics in Anthropological Studies of Culture", Berghahn Oxford New York 2006:211-224

Buchheit, Klaus Peter: "The World as Negro and déjà vue" (an essay on Adolf Bastian and the self-deconstructing infringements of Buddhism, jargon, and racism as means of intercultural diagnosis), in: Manuela Fischer, Peter Bolz, Susan Kamel (eds.), "Adolf Bastian and his universal archive of humanity. The origins of German anthropology." Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim, Zürich, New York, 2007:39-44

Koepping, Klaus-Peter (1983) "Adolf Bastian and the Psychic Unity of Mankind: The Foundations of Anthropology in Nineteenth Century Germany". St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Lowie, Robert (1937) "The History of Ethnological Theory". Holt Rhinehart (contains a chapter on Bastian).

Tylor, Edward B. (1905) "Professor Adolf Bastian." "Man" 5:138-143.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.