- Eric Hermelin

Infobox Person

name = Eric Hermelin

image_size =

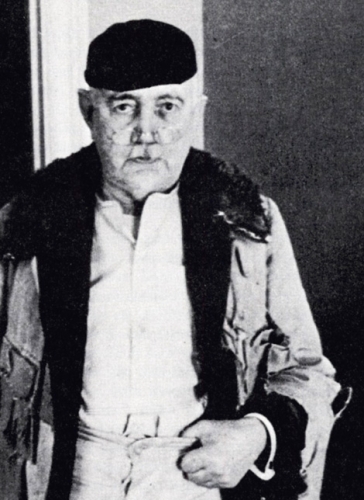

caption = Eric Hermelin in his sheepskin coat, ca. 1940

birth_name = Eric Axel Hermelin

birth_date = birth date|1860|06|22

birth_place = Svanshals,Sweden

death_date = Death date|1944|11|08

death_place =Lund , Sweden

death_cause =

resting_place =

resting_place_coordinates =

residence =

nationality = Swedish

ethnicity = Swedish

citizenship =

other_names =Thomas Edward Hallan

known_for = Translation ofPersian literature

education = University ofUppsala

alma_mater =

employer =

occupation =

home_town =

title =

salary =

networth =

height =

weight =

term =

predecessor =

successor =

party =

boards =

religion =

spouse = never married

partner =

children =

parents =

relations =

website =

footnotes =Eric Axel Hermelin, Baron Hermelin (

June 22 ,1860 –November 8 ,1944 ) was a Swedish author and prolific translator of Persian works of literature.Biography

Hermelin was born into an aristocratic family in Svanshals, south

Sweden , and had a traditional education, at the end of which he spent a couple of years at the Philosophical Faculty of the University ofUppsala , which he left without taking a degree. Already at this stage he seems to have developed a taste for alcohol, which later became an addiction, with drastic life-long consequences. After an unsuccessful attempt at farming on a family estate, he began a wandering life abroad. In 1883 he went to the United States and eked out a living as a teacher, a carpenter, and a soldier, before returning toEurope in 1885. In 1886 he traveled toEngland and joined the British army as a soldier in the Middlesex Regiment (under the name ofThomas Edward Hallan ). He went with his regiment toIndia in the following year. However, his army career in India proved a failure. He was much troubled by disease, and by then his drinking had developed into full-blown alcoholism, possibly in combination with the use of narcotic drugs. Nevertheless, he spent time on language studies, obviously in preparation for one of the language examinations that formed part of the British administrative system inIndia . He states that he learntHindustani (i.e.,Urdu ) and also started to learn Persian. There is, however, no record showing that he had passed any examination in these subjects. In later years he occasionally referred to hisIndia n "Monshi," and it is also likely that he had his first encounters withSufism at that time. In April 1893 he was finally discharged from the army "with ignominy," i.e., for disciplinary reasons. After that he became an even more intrepid traveler, going toEngland and America (includingJamaica ) and then back toSweden , where he again tried his hand at farming. His aristocratic family found his alcoholism and disorderly life unacceptable and had him declared officially unfit to manage his life, and in 1897 he was placed under the care of a guardian. Regardless of this injunction, he went abroad again and lived inAustralia and, possibly, America, earning a living through sundry occupations. He turned up inLondon in the autumn of 1907 and returned toSweden in early 1908. In the autumn of the same year he was taken into a lunatic asylum inStockholm , and in February 1909 he was moved to the asylum of St. Lars inLund , where he spent the rest of his life. He never married.Writing works

There is no concrete evidence of any literary production from his years of travel, but he turned to reading and writing when he was confined to the asylum in

Lund . He began as a conservative and patriotic writer of verses, commentaries, and translations in local daily newspapers; but through his reading of, among others, the English socialistRobert Blatchford , he gradually adopted a more liberal and even radical attitude. Soon he was attracted by mysticism, first of all byEmanuel Swedenborg , whose works he started to translate. Then he turned to theChristian quietism and mysticism ofJakob Böhme , who remained one of his main inspirations. In this context he resumed his Persian studies and also started to learnHebrew . Against all odds, with repeated lapses into alcoholism and deep depressions, he began a new career as an author and translator. His first publication (Uppsala , 1913) was a Swedish translation of an English work byAlexander Whyte onJakob Böhme . In 1918 two volumes of translations from works by Böhme appeared in print, and the same year saw his first publication of a Swedish translation from Persian, the "Bustan" ofSa'di , possibly first encountered by him when he was preparing for his Persian examination inIndia some thirty years earlier. It was the first in a long series of Persian translations of classical Persian literature by his hand.In the period 1918-43 he published no less than 23 volumes, altogether more than 8000 pages, of such translations. After the "Golestan" came an anthology of robaiyyat and mathnawiyyat, then Shabestari's "Golshan-e raz", the "Robaiyyyat" of

Khayyam , an abridged version ofSana'i 's "Hadiqat-al-haqiqa" and the "Anwar-e sohayli" ofWa'ez Kashefi . However, the greatest achievement of Hermelin was his translation of works byFarid al-din 'Attar andJalal-al-Din Rumi . BothFarid al-din 'Attar 's "Pand-nama" and his "Manteq al-tayr" appeared in print in 1929, his "Tazkerat al-awlia" in four volumes in 1931-43, and the "Masnawi" ofJalal al-Din Rumi in six volumes in 1933-39. In between he also published translations of excerpts from the "Shah-nama" and the full texts of the "Kalila o Demna" andNezami 's "Eskandar-nama".Thanks to Hermelin's prodigious output, there were already in the 1940s more translations of classical Persian literature available in Swedish than in most other

Europe an languages. The impact of these translations was, however, fairly limited. As a patient in a lunatic asylum, he remained a marginal figure, and most of his translations were printed privately, paid for by the family. Furthermore, he had an old-fashioned, and at times even odd and idiosyncratic, style in Swedish. He made liberal use of capitals for emphasis and excelled in some quasi-etymological erroneous conjectures such as substituting 'Omr ("life") for 'OmarKhayyam ). On the whole however, his translations are reliable and exact, only occasionally misinterpreting phraseology not easily found in the standard works of reference available to him (Salemann-Zhukovski's "Grammar" and Steingass's "Dictionary", etc.). At times his style acquires a strong and original, even prophetic, ring that made it especially attractive to poets and writers, such asVilhelm Ekelund ,Hjalmar Gullberg andGunnar Ekelöf . Similarly, the very personal kind of mysticism that he developed through the years has had more impact as a literary model than as an exegesis ofSufism . His work strikes a grandiose but solitary chord in Swedish writing and Persian scholarship of the 20th century.ee also

*

Persian literature

*Sufism

*Ashk Dahlén References

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.