- Death of Ayrton Senna

-

The death of three-time Formula One World Champion Ayrton Senna on May 1, 1994, occurred as a result of his car crashing into a concrete barrier while he was leading the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix at the Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari in Italy. The previous day, Roland Ratzenberger had been killed when his car crashed during qualification for the race. His and Senna's accidents were the worst of several accidents that took place that weekend and were the first fatal accidents to occur during a Formula One race meeting in twelve years. They became a turning point in the safety of Formula One, prompting the implementation of new safety measures and the re-formation of the Grand Prix Drivers' Association.

While Senna's crash remains the most recent to claim the life of a Formula 1 driver, two accidents have since claimed the lives of trackside marshals.

Contents

Background

On May 1, 1994, Senna took part in his third race for the Williams team, the San Marino Grand Prix at the Imola circuit. Although he would not finish it, Senna started his final Formula One race from pole position.

That weekend, he was particularly upset by two events. On Friday, during the afternoon qualifying session, Senna's protégé, F1 newcomer Rubens Barrichello, was involved in a serious accident that prevented him from competing in the race. On Saturday, the death of Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger in qualifying deeply upset Senna, reinforcing his safety concerns and made him consider retiring from the sport. Ironically, he spent his final morning meeting fellow drivers, determined after Ratzenberger's accident to take on a new responsibility to re-create the Grand Prix Drivers' Association, a Drivers' Safety group to increase safety in Formula One. As the most senior driver, he offered to take the role of leader in this effort.

Accident

On Sunday, Pedro Lamy and JJ Lehto were involved in a starting-line accident. Track officials deployed the Opel Vectra safety car, driven by Max Angelelli at the time, to slow down the field and allow the debris from the starting accident to be removed. The cars proceeded under the safety car for 5 laps.

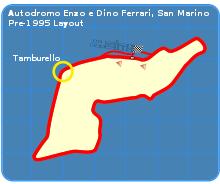

On lap 7, from the onboard camera of Michael Schumacher's Benetton, Senna's car was seen to bottom out heavily (as on the previous lap and during his first laps in the warmup session) and then seen to break traction twice at the rear and strike an unprotected concrete barrier at Tamburello corner. Telemetry shows he left the track at 310 km/h (190 mph) and was able to slow the car down by braking to 218 km/h (135 mph) in slightly under 2 seconds before hitting the wall.

A map of the circuit per 1994 layout, with the Tamburello corner encircled.

A map of the circuit per 1994 layout, with the Tamburello corner encircled.

The car understeered strongly off the track, hit the wall at a shallow angle, tearing off the right front wheel and nose cone, lifted slightly with the nose as it straightened, and spun to a halt. After Senna's car came to a halt, he remained motionless in the cockpit.

After the crash it was immediately evident that Senna had suffered some form of injury, because of the manner in which his helmet was seen to be motionless and leaning slightly to the side. In the seconds that followed his head was seen to move to one side slightly, causing false hopes to be raised. A considerable amount of time passed before medical units came to his aid, with fire marshals having arrived at the car and unable to touch Senna before qualified medical personnel arrived. Television coverage from an overhead helicopter was seen around the world, as rescue workers gave medical attention. Close inspection of the area in which the medical staff treated Senna revealed a considerable amount of blood on the ground. From visible injuries to Senna's head it was evident to attending medical professionals that Senna had sustained a grave head trauma. An emergency tracheotomy was conducted trackside to artificially induce breathing on Senna. The race was stopped 1 minute 9 seconds after Senna's crash.

Approximately 10 minutes after Senna's crash, a miscommunication in the pits caused a Larrousse car piloted by Érik Comas to leave the pit lane and attempt to rejoin the now red flagged Grand Prix. That incident with Comas was spotted by Eurosport Commentator John Watson as the "most ridiculous incident I ever saw at any time in my life". Frantic waving by the marshals at Senna's crash site prevented the Larrousse from risking a collision with the medical helicopter that had landed on the track.

Professor Sidney Watkins, a world-renowned neurosurgeon, Formula One Safety Delegate and Medical Delegate, and the head of the Formula One on-track medical team, performed the on-site tracheotomy on Ayrton Senna.[1]

Watkins later reported:

He looked serene. I raised his eyelids and it was clear from his pupils that he had a massive brain injury. We lifted him from the cockpit and laid him on the ground. As we did, he sighed and, although I am not religious, I felt his spirit depart at that moment.[2]

Some time later, Bob Jenkins of NASCAR on ESPN relayed the news of Senna's death to American viewers during the Winston Select 500 just as the drivers were coming to the restart.

Autopsy

Senna was 34 years old at the time of his death. What had likely happened was that the right front wheel had shot up upon impact and entered the cockpit area where Senna was sitting.[3] It struck the right frontal area of his helmet, and the violence of the wheel’s impact pushed his head back against the headrest, causing fatal skull fractures.[3] A piece of upright attached to the wheel had partially penetrated his Bell M3 helmet and caused a trauma to his head.[3] In addition, it appeared that a jagged piece of the upright assembly had penetrated the helmet visor just above his right eye.[3] Senna was using a medium sized (58 cm) M3 helmet with a new "thin" Bell visor. Any one of the three injuries would probably have killed him.[3]

The FIA and Italian authorities still maintain that Senna was not killed instantly, but rather died in hospital, where he had been rushed by helicopter after an emergency tracheotomy and IV administration were performed on track. There is an ongoing debate as to why Senna was not declared dead at the track. Under Italian law when a person dies at a sporting event, that death must be investigated, causing the sporting event to be cancelled. The former Director of the Oporto (Portugal) Legal Medicine Institute, Professor José Eduardo Pinto da Costa, has stated the following:

From the ethical viewpoint, the procedure used for Ayrton's body was wrong. It involved dysthanasia, which means that a person has been kept alive improperly after biological death has taken place because of brain injuries so serious that the patient would never have been able to remain alive without mechanical means of support. There would have been no prospect of normal life and relationships. Whether or not Ayrton was removed from the car while his heart was beating or whether his supply of blood had halted or was still flowing, is irrelevant to the determination of when he died. The autopsy showed that the crash caused multiple fractures at the base of the cranium, crushing the forehead and rupturing the temporal artery with haemorrhage in the respiratory passages. It is possible to resuscitate a dead person immediately after the heart stops through cardio-respiratory processes. The procedure is known as putting the patient on the machine. From the medical-legal viewpoint, in Ayrton's case, there is a subtle point: resuscitation measures were implemented. From the ethical point of view this might well be condemned because the measures were not intended to be of strictly medical benefit to the patient but rather because they suited the commercial interest of the organisation. Resuscitation did in fact take place, with the tracheotomy performed, while the activity of the heart was restored with the assistance of cardio-respiratory devices. The attitude in question was certainly controversial. Any physician would know there was no possibility whatsoever of successfully restoring life in the condition in which Senna had been found.[4]

Professor Jose Pratas Vital, Director of the Egas Moniz hospital in Lisbon, a neurosurgeon and Head of the Medical Staff at the Portuguese GP, offered a different opinion:

The people who conducted the autopsy stated that, on the evidence of his injuries, Senna was dead. They could not say that. He had injuries which led to his death, but at that point the heart may still have been functioning. Medical personnel attending an injured person, and who perceive that the heart is still beating, have only two courses of action: One is to ensure that the patient's respiratory passages remain free, which means that he can breathe. They had to carry out an emergency tracheotomy. With oxygen, and the heart beating, there is another concern, which is loss of blood. These are the steps to be followed in any case involving serious injury, whether on the street or on a racetrack. The rescue team can think of nothing else at that moment except to assist the patient, particularly by immobilising the cervical area. Then the injured person must be taken immediately to the intensive care unit of the nearest hospital.[4]

Rogério Morais Martins, creative director of Ayrton Senna Promotions (which became the Ayrton Senna Institute after Senna's death), stated that:

According to the first clinical bulletin read by Dr. Maria Teresa Fiandri at 4.30 pm Ayrton Senna had brain damage with haemorrhaged shock and deep coma. However, the medical staff did not note any chest or abdomen wound. The haemorrhage was caused by the rupture of the temporal artery. The neurosurgeon who examined Ayrton Senna at the hospital mentioned that the circumstances did not call for surgery because the wound was generalised in the cranium. At 6.05 pm Dr. Fiandri read another communiqué, her voice shaking, announcing that Senna was dead. At that stage he was still connected to the equipment that maintained his heartbeat. The release by the Italian authorities of the results of Ayrton Senna's autopsy, revealing that the driver had died instantaneously during the race at Imola, ignited still more controversy. Now there were questions about the reactions of the race director and the medical authorities. Although spokespersons for the hospital had stated that Senna was still breathing on arrival in Bologna, the autopsy on Ratzenberger [who died the day before] indicated that death had been instantaneous. Under Italian law, a death within the confines of the circuit would have required the cancellation of the entire race meeting. That, in turn, could have prevented Senna's death. The relevant Italian legislation stipulates that when a death takes place during a sporting event, it should be immediately halted and the area sealed off for examination. In the case of Ratzenberger, this would have meant the cancellation of both Saturday's qualifying session and the San Marino Grand Prix on Sunday. Medical experts are unable to state whether or not Ayrton Senna died instantaneously. Nevertheless, they were well aware that his chances of survival were slight. Had he remained alive, the brain damage would have left him severely handicapped. Accidents such as this are almost always fatal, with survivors suffering irreversible brain damage. This is a result of the effects on the brain of sudden deceleration, which causes structural damage to the brain tissues. Estimates of the forces involved in Ayrton's accident suggest a rate of deceleration equivalent to a 30 metre vertical drop, landing head-first. Evidence offered at the autopsy revealed that the impact of this 208 km/h crash caused multiple injuries at the base of the cranium, resulting in respiratory insufficiency. There was crushing of the brain (which was forced against the wall of the cranium causing oedema and haemorrhage, increasing intra-cranial pressure and causing brain death), together with the rupture of the temporal artery, haemorrhage in the respiratory passages and the consequent heart failure. There are two opposing theories on the issue of whether the drivers were still alive when they were put in the helicopters that carried them to hospital. Assuming both Ratzenberger and Senna had died instantaneously, the race organisers might have delayed any announcement in order to avoid being forced to cancel the meeting, thus protecting their financial interests. Had the meeting been cancelled, Sagis – the organisation which administers the Imola circuit – stood to lose an estimated US$6.5 million.[4]

Funeral

Senna's death was considered by many of his Brazilian fans to be a national tragedy, and the Brazilian government declared three days of national mourning. Contrary to airline policy and out of respect, Senna's coffin was allowed to be flown back to his home country not as cargo but in the passenger cabin of Varig's McDonnel-Douglas MD-11 commercial jetliner (registration PP-VOQ (cn 48435/478)), accompanied by his distraught younger brother, Leonardo, and close friends.

An estimated three million people lined the streets of his hometown of São Paulo to offer him their salute. Many prominent motor racing figures attended Senna's state funeral, notably Alain Prost, Jackie Stewart, Damon Hill and Emerson Fittipaldi who were among the pallbearers. However, Senna's family did not allow FOM president Bernie Ecclestone to attend,[5] and FIA President Max Mosley instead attended the funeral of Ratzenberger which took place on 7 May 1994, in Salzburg, Austria.[6] Mosley said in a press conference ten years later, "I went to his funeral because everyone went to Senna's. I thought it was important that somebody went to his."[7] Senna was buried at the Morumbi Cemetery in his hometown of São Paulo. His grave bears the epitaph "Nada pode me separar do amor de Deus", which means "Nothing can separate me from the love of God" (a reference to Romans 8:38-39[8]).

A testament to the adulation he inspired among fans worldwide was the scene at the Tokyo headquarters of Honda where the McLaren cars were typically displayed after each race. Upon his death, so many floral tributes were received that it overwhelmed the large exhibit lobby.[9] This in spite of the fact Senna no longer drove for McLaren and that McLaren, in the preceding seasons did not use Honda power. Senna had a special relationship with company founder Soichiro Honda[citation needed] and was beloved in Japan where he achieved a near mythic status. For the next race at Monaco, the FIA decided to leave the first two grid positions empty and painted them with the colours of the Brazilian and the Austrian flags, to honour Senna and Ratzenberger.

Trial

The Williams team was entangled for many years in a court case with the Italian prosecutors over manslaughter charges, ending in a guilty verdict for Patrick Head. The Italian Court of Appeal, on April 13, 2007, stated the following in the verdict numbered 15050: "It has been determined that the accident was caused by a steering column failure. This failure was caused by badly designed and badly executed modifications. The responsibility of this falls on Patrick Head, culpable of omitted control". Even being found responsible for Senna's accident, Patrick Head wasn't arrested: in Italy the statute of limitation for manslaughter is 7 years and 6 months, and the final verdict was pronounced 13 years after the accident.[10]

A 600-page technical report was submitted by Bologna University under Professor of Engineering Enrico Lorenzini and his team of specialists. The report concluded that fatigue cracks had developed through most of the steering column at the point where it had broken.[11] Lorenzini stated: "It had been badly welded together about a third of the way down and couldn't stand the strain of the race. We discovered scratches on the crack in the steering rod. It seemed like the job had been done in a hurry but I can't say how long before the race. Someone had tried to smooth over the join following the welding. I have never seen anything like it. I believe the rod was faulty and probably cracked even during the warm-up. Moments before the crash only a tiny piece was left connected and therefore the car didn't respond in the bend."[12]

Senna did not like the position of the steering column relative to his seating position and had repeatedly asked for it to be changed. Patrick Head and Adrian Newey agreed to Senna's request to lengthen the FW16's steering column, but there was no time to manufacture a longer steering shaft. The existing shaft was instead cut, extended by inserting a smaller-diameter piece of tubing and welded together with reinforcing plates. Many surmise, based on the "yellow button tracking analysis" done in 1997 by CINECA that the movement of the steering wheel during the final seconds into Tamburello was abnormal. A reference point (yellow button) on the onboard video is seen to move several centimetres in its own plane, because of the steering wheel moving up and down, indicating a fully or partially buckled steering column.

Williams released its own video to prove the movement was normal by Coulthard manhandling an FW16B steering wheel, yet the effort required by Coulthard to deflect the wheel in the demonstration is termed to be "quite considerable". The nature of Tamburello requiring a light and anticipatory grip on the wheel (because of the high speed and bumps) coupled with Senna's slight frame causes some[who?] to question whether or not the movement of the yellow button was indeed as "normal" as Williams has claimed.

During the trials,[13] Fabrizio Nosco, a Regional technical commissioner, testified that both of the vehicle's black boxes were intact, except for minor scratches. He said "I have seen thousands of these devices and removed them for checks. The two boxes were intact, even though they had some scratches. The Williams device looked to have survived the crash.". In a move that apparently breached FIA regulations, Charles Whiting, a FIA official, handed the black boxes to Williams before the regulating body's own investigation into the accident. Williams claimed the black boxes were unreadable, and the boxes returned for the court proceedings were indeed unreadable, a full month after the accident. The black boxes might have put to rest the cause of the accident.

At the conclusion of the Italian trial, Senna's FW16, chassis number 02, was returned to the Williams team. The team reported that the car was in an advanced state of deterioration and was subsequently destroyed. The car's engine was returned to Renault, and its fate is unknown.[14]

In May 2011, Williams FW16 designer Adrian Newey expressed his views on the accident: "The honest truth is that no one will ever know exactly what happened. There's no doubt the steering column failed and the big question was whether it failed in the accident or did it cause the accident? It had fatigue cracks and would have failed at some point. There is no question that its design was very poor. However, all the evidence suggests the car did not go off the track as a result of steering column failure... If you look at the camera shots, especially from Michael Schumacher's following car, the car didn't understeer off the track. It oversteered which is not consistent with a steering column failure. The rear of the car stepped out and all the data suggests that happened. Ayrton then corrected that by going to 50% throttle which would be consistent with trying to reduce the rear stepping out and then, half-a-second later, he went hard on the brakes. The question then is why did the rear step out? The car bottomed much harder on that second lap which again appears to be unusual because the tyre pressure should have come up by then – which leaves you expecting that the right rear tyre probably picked up a puncture from debris on the track. If I was pushed into picking out a single most likely cause that would be it."[15]

Legacy

Following the deaths of Senna and Ratzenberger, many safety improvements were made. Although other drivers had died before him, Senna had arguably been the highest profile. Improved crash barriers, redesigned tracks and tyre barriers, higher crash safety standards, and higher sills on the driver cockpit are among the measures that were subsequently introduced. Since Senna's death, no drivers have died behind the wheel of a Formula One car, despite large accidents still occurring. The FIA immediately investigated the Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari in Imola, and the track's signature Tamburello turn, was changed into a left-right chicane.

At the hospital it was revealed that nurses had discovered a small furled Austrian flag hidden in the sleeve of Senna’s race overalls. Journalists concluded he had intended to fly it from his cockpit after the race, and dedicate what would have been his 42nd Grand Prix victory to the memory of Roland Ratzenberger.[1]

At his funeral an estimated three million people lined the streets of his home town of São Paulo to give him their salute.

Senna remains the most recent driver to die in a Formula 1 crash. However, two trackside marshals have been killed since then as a result of flying debris from crashes. These fatalities occurred at the 2000 Italian Grand Prix and the 2001 Australian Grand Prix.

Notes and references

- ^ a b "8W – Who? – Ayrton Senna". Forix.com. http://www.forix.com/8w/senna1994.html. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ Watkins, Sid (1996). Life at the Limit: Triumph and Tragedy in Formula One. Pan Books. p. 10. ISBN 0-330-35139-7.

- ^ a b c d e "SportsPro: Sport's money magazine". February 25, 2008. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080225170106/http://www.sportspromedia.com/senna.htm. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c "The Senna Files: Ayrton Senna trial news etc : NewSfile No.2". Ayrton Senna. http://www.ayrton-senna.com/s-files/newsfle2.html. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "'Senna would have beaten Schumacher in equal cars' – Motor Racing, Sport". The Independent (UK). 22 April 2004. http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/motor-racing/senna-would-have-beaten-schumacher-in-equal-cars-560807.html. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ^ David Tremayne, Mark Skewis, Stuart Williams, Paul Fearnley (5 April 1994). "Track Topics". Motoring News (News Publications Ltd.).

- ^ "Max went to Roland's funeral". www.f1racing.net. 23 April 2004. http://www.f1racing.net/en/news.php?newsID=48657. Retrieved 28 October 2006.

- ^ Romans 8:38-39, NIV

- ^ "アイルトン・セナの去った夜" (in Japanese). http://www.honda.co.jp/collection-hall/episodes_old/motor/mp44/index.html.

- ^ "Senna, Head "responsabile" – Gazzetta dello Sport". Gazzetta.it. http://www.gazzetta.it/Motori/Formula1/Primo_Piano/2007/04_Aprile/13/senna.shtml. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Williamsdispute Senna findings – Sport". The Independent. UK. March 29, 1996. http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/williamsdispute-senna-findings-1344727.html. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Williams fear Senna fall-out – Sport". The Independent. UK. December 17, 1995. http://www.independent.co.uk/sport/williams-fear-senna-fallout-1526203.html. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ "Ayrton Senna THE SENNA FILES Ayrton Senna trial news etc : NewSfile No.5". Ayrton-senna.com. February 16, 1997. http://www.ayrton-senna.com/s-files/newsfle5.html. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ Tom Rubython, "Life of Senna", chapter 33, "The Trial", pg.473.

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/sport/2011/may/16/adrian-newey-ayrton-senna-death

See also

- List of Formula One fatal accidents

- 1994 San Marino Grand Prix

- Death of Dale Earnhardt – another fatal crash whose impact on NASCAR was similar to that of Senna's crash on F1

Categories:- 1994 in Formula One

- 1994 in Brazil

- 1994 in Italy

- Conspiracy theories

- Deaths by person

- Filmed deaths in sports

- Sport deaths in Italy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.