- Nicolas Jenson

-

Nicolaus Jenson, portrait

Nicolaus Jenson, portrait

Nicolas Jenson (1420 in Sommevoire, France – 1480 in Venice, Italy) was a French engraver, pioneer printer and type designer who accomplished most of his work in Venice. Jenson acted as Master of the French Royal mint at Tours, and is accredited with being the creator of the first model roman type. [1] Nicholas Jenson has been something of cult figure among students of early printing since the nineteenth century when the aesthete William Morris canonized him as one of the patron saints of typography because of the beauty and perfection of his roman font. Apart from any qualitative judgments, just the sheer number of Jenson’s editions (108 between 1470 and 1481 according to Lowry) makes him an important figure in the early history of printing and a pivotal force in the emergence of Venice as one of the first great centers of the printing press..[2]

Contents

History

In October of 1458, while acting as Master of the French royal mint, Jenson was sent to Mainz, by King George VII, to study the art of metal movable type. Jenson then went to Mainz to study printing under Johannes Gutenberg. In 1470 he opened a printing shop in Venice, and, in the first work he produced, the printed roman lowercase letter took on the proportions, shapes, and arrangements that marked its transition from an imitation of handwriting to the style that has remained in use throughout subsequent centuries of printing. Jenson also designed Greek-style type and black-letter type. Although he composed his types in a meticulously even style, he did not always print them with the accuracy they deserved. Nonetheless, he published more than 150 titles, soundly edited by scholars of authority.[3] From whom Jenson learned this is in question. Some hypothesize that Jenson studied under the tutelage of Gutenberg. However, there is no historically verifiable evidence of this. By this time Gutenberg's first press had been seized by Johann Fust, and historians are unsure of his activities during this period. Further, by the time Jenson arrived in Mainz, there were a number of established printers under which he could have apprenticed. Jenson left Mainz in 1461, but with no desire to return to France after King Charles' death in 1461, as he had he had little desire to return under the new rule of Louis XI. Jenson came to Venice in 1468, where he opened his own printing workshop, eventually producing around 150 titles. In the first work he produced, the printed roman lowercase letter took on the proportions, shapes, and arrangements that marked its transition from an imitation of handwriting to the style that has remained in use throughout subsequent centuries of printing. Jenson also designed Greek-style type and black-letter type. By the end of his life Jenson was a wealthy man, producing liturgical, theological and legal texts in a variety of gothic fonts, the roman type left only for the odd commissioned work..[4]

Printing History

During the 1470’s Nicholas Jenson’s technical skill and business acumen helped establish Venice as Italy’s publishing capital and in centuries since he has been celebrated for perfecting roman type, the rebirth of Latin inscription. But what set Jenson apart from other printers was his constant drive to expand fis financial base beyond the patronage system. Wishing to invade the untapped market of the university textbooks, he built a team of Italian banking families and German merchants-speculators and, armes with capital, by 1477 he could run as many as 12 presses simultaneously. In order to lower prices and force out less productive rivals, he cut cursive gothic type, enabling him to print text and gloss on the same page for the first time in history..[5]

The Typeface

Jenson's fame as one of history's greatest typeface designers and punch cutters rests on the types first used in Eusebiu's De praeparatione evangelica, which presents the full flowering of roman type design.

Capitals of Nicolas Jenson's roman typeface, from a translation 'in fiorentina' (in Italian) of Pliny the Elder, published in Venice in 1476.

Capitals of Nicolas Jenson's roman typeface, from a translation 'in fiorentina' (in Italian) of Pliny the Elder, published in Venice in 1476.

Jenson constructed his first roman typeface deliberately on the basis of typographical principles, as opposed to the old manuscript models. It was first employed in his 1470 edition of Eusebius, De Evangelica Praeparatione. In 1471, a Greek typeface followed, which was used for quotations, and then in 1473 a Black Letter typeface, which he used in books on medicine and history.Jenson was set apart from other printers because he was able to expand his financial base beyond the patronage system. Wishing to incade the relatively untapped market of university textbooks, he built a team of Italian banking families and German merchant-speculators and, armed with capital, by 1477 could run as many as twelve presses simultaneously.[6] He is also responsible for launching two book trading companies, first in 1475 and then in 1480, under the name of Johannes de Colonia, Nicolaus Jenson et socii. A particular advertisement from 1482 exhorts Jenson's books:

Do not hinder one's eyes, but rather help them and do them good. Moreover, the characters are so intelligently and carefully elaborated that the letters are neither smaller, larger nor thicker than reason or pleasure demand.Following his death in 1480, his respective typefaces were employed by the Aldine Press,[7] and have continued to be the basis for numerous fonts. Examples include Bruce Rogers' "Centaur" in 1914, Morris Fuller Benton's "Cloister Old Style" in 1926, and Robert Slimbach's "Adobe Jenson" in 1996. [8]

Published Works

By 1472, Jenson had only been printing for two years. Even so, his roman type quickly became the model for what later came to be called Venetian oldstyle and was widely imitated. Though Jenson's type was soon superceded in popularity by those of Aldus and Garamond, it was revived again by William Morris in the late 19th century and became the model of choice for a number of private press printers.[9]

Julius Caesar Works, printer Nicolas Jenson, 1471

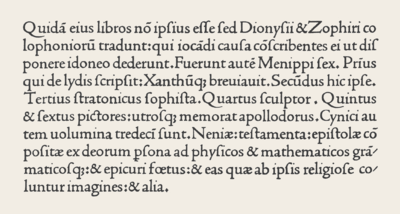

Julius Caesar Works, printer Nicolas Jenson, 1471 Roman type of Nicholas Jenson, 1472

Roman type of Nicholas Jenson, 1472Venetian publishing in Renaissance Europe

See also

References

- ^ Bullen, Henry Lewis. Nicolas Jenson, Printer of Venice: His famous type designs and some comment upon the printing types of earlier printers. San Francisco. Printed by John Henry Nash.(1926)

- ^ Nicholas Jenson and the rise of Venetian publishing in Renaissance Europe / Martin Lowry. Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA : B. Blackwell, 1991. xvii, 286 p., [16] p. of plates : ill. ; 24 cm.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/302641/Nicolas-Jenson

- ^ Nicholas Jenson and the rise of Venetian publishing in Renaissance Europe / Martin Lowry. Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA : B. Blackwell, 1991. xvii, 286 p., [16] p. of plates : ill. ; 24 cm.

- ^ Nicholas Jenson and the rise of Venetian publishing in Renaissance Europe / Martin Lowry. Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA : B. Blackwell, 1991. xvii, 286 p., [16] p. of plates : ill. ; 24 cm.

- ^ James E. Stark Libraries & Culture Vol. 28, No. 3 (Summer, 1993) (pp. 343-344)

- ^ Nicolas Jenson. (2010). Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, 1. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

- ^ "Nicolas Jenson." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2011. Web. 06 Oct. 2011. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/302641/Nicolas-Jenson>.

- ^ Nicholas Jenson and the rise of Venetian publishing in Renaissance Europe / Martin Lowry. Oxford, UK ; Cambridge, Mass., USA : B. Blackwell, 1991. xvii, 286 p., [16] p. of plates : ill. ; 24 cm.

- ^ Lowry, Martin: Venetian Printing. The Rise of the Roman Letterform. With an Essay by George Abrams. EWdited, introduced and translated into Danish by Poul Steen Larsen. Herning: Poul Kristensens Fporlag, 1989. The first book to present the typeface Abrams Venetian, designed by George Abrams.

v. Lieres, Dr. Vita. "Nicolaus Jenson." in: Schriftgießerei D. Stempel AG [ed.]: Altmeister der Druckschrift. Frankfurt am Main, 1940. (pp. 35–40). (In German)

External links

Categories:- 1420 births

- 1480 deaths

- Typographers

- 15th-century French people

- French printers

- Printers of incunabula

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.