- Charles Hamilton (writer)

-

For other people named Charles Hamilton, see Charles Hamilton (disambiguation).

Charles Hamilton

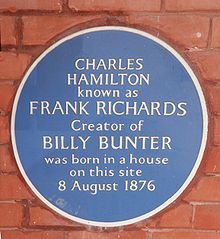

Hamilton on the cover of his Autobiography under his pen name of Frank RichardsBorn Charles Harold St. John Hamilton

8 August 1876

Ealing, LondonDied 24 December 1961 (aged 85)

Kingsgate, KentOccupation Author Nationality English Notable work(s) Billy Bunter Charles Harold St. John Hamilton (8 August 1876 – 24 December 1961), was an English writer, specializing in writing long-running series of stories for weekly magazines about recurrent casts of characters, his most frequent and famous genre being boys' public school stories, though he also dealt with other genres. He used a variety of pen-names, generally using a different name for each set of characters he wrote about, the most famous being Frank Richards for the Greyfriars School stories (featuring Billy Bunter). Other important pen-names included Martin Clifford (for St Jim's), Owen Conquest (for Rookwood), Peter Todd (for Herlock Sholmes) and Ralph Redway (for The Rio Kid). He also wrote some stories under his real name such as the Ken King stories for the Modern Boy.

He is estimated to have written about 100 million words in his lifetime (Lofts & Adley 1970:170) and has featured in the Guinness Book of Records as the world's most prolific author.

Contents

Working Life

Early life and career - 1876-1906

Hamilton was born in Ealing, London to a family of eight children. He began a career as a writer of fiction having his first story accepted almost immediately. Over the following years he was to establish himself as the main writer with the publisher, Trapps Holmes, providing several thousand stories on a range of subjects including police, detectives, firefighters, Westerns as well as school stories. In 1906 he started to write for the Amalgamated Press and although he continued to have stories published for Trapps Holmes until 1915 (many of which were reprints), his allegiance was gradually to move (Lofts & Adley 1975:25–42).

Heyday – 1907-1940

Amalgamated Press started a new story paper for boys called The Gem in 1907 and by issue number 11 it had established a format – the major content was to be a story about St Jim’s school, starring Tom Merry as the main character and written by Charles Hamilton under the pen name of Martin Clifford. This paper rapidly established itself and anxious to capitalize on its success, a similar venture was launched in 1908. This was to be known as The Magnet, the subject matter was a school called Greyfriars and Hamilton was again to be the author, this time using the name Frank Richards (Lofts & Adley 1975:43–51) .

In 1915, Hamilton started a third school for Amalgamated Press, Rookwood, this time under the name Owen Conquest and featuring a leading character called Jimmy Silver. These appeared as part of the Boys' Friend Weekly publication and were shorter than the Greyfriars and St Jim’s stories (Lofts & Adley 1975:52–55).

These three schools were to absorb most of Hamilton’s efforts over the next three decades and constitute the work for which he is best remembered. In the early days of this period, the St Jim’s stories were more involved and more popular. The Greyfriars stories however, evolved gradually over the early years of the Magnet, eventually becoming Hamilton’s main priority. In all he provided stories for 82% of the issues of The Magnet compared with two thirds of the issues of the Gem. If a Hamilton story was not available, the story was provided by another author but still using the Clifford or Richards name (Lofts & Adley 1975:52–72) .

The Gem carried on until December 1939 and by then the circulation of the Magnet had also declined. With England facing a paper shortage the closure of the paper was inevitable and this came about in 1940.

Late career – 1940-1961

Following the closure of The Magnet in 1940, Hamilton had little work but he became known as the author of the stories following a newspaper interview he gave to the London Evening Standard. He was not however able to continue the Greyfriars saga as Amalgamated Press held the copyright and would not release it.

In the event he was obliged to create new schools such as Carcroft and Sparshott, as well as trying the romance genre under the name of Winston Cardew. By 1946 however, he had received permission to write Greyfriars stories again and obtained a contract from publishers Charles Skilton for a hardback series the first volume of which, Billy Bunter of Greyfriars School, was published in September 1947. The series was to continue for the rest of his life, the publisher later changing to Cassells. In addition, he wrote further St Jim’s, Rookwood and Cliff House stories, as well as the television script for seven series of Billy Bunter stories for the BBC (Lofts & Adley 1975:146–151).

He died on 24 December 1961, aged 86.

Personal life

Rose Lawn, Kent

Rose Lawn, Kent

Hamilton never married but some details of a romance is provided in a biography, and another is briefly mentioned in his autobiography. Early in the 20th century, he was briefly engaged to a lady called Agnes, and later he formed a brief attachment to an American lady whom he alluded to as Miss New York.

His life interests were writing stories, studying Latin, Greek, and modern languages, chess, music, and gambling, especially at Monte Carlo. The Roman poet and author Horace was a particular favourite. He travelled widely in Europe in his youth, but never left England after 1926, living in a small house called Rose Lawn, at Kingsgate, Kent, looked after by his housekeeper, Miss Edith Hood. She continued to reside in Rose Lawn following his death in 1961.

While Hamilton was reclusive in later years, he had a prolific letter correspondence with his readers. He generally wore a skull cap to conceal his hair loss and sometimes smoked a pipe.

He had a close relationship with his sister Una, and her daughter, his niece, Una Hamilton Wright, who produced her own biography of Hamilton in 2006 (Hamilton Wright & McCall 2006). He also got along very well with Percy Harrison his brother-in-law, and the husband of his sister Una.

His stories were typed out utilizing a purplish ribbon and with little revision on a Remington Standard 10 typewriter. Previously from around the year 1900 to 1922, he utilized a Remington Standard 7 typewriter.

Output

Extent

Main article: List of stories by Charles HamiltonIt has been estimated by researchers Lofts and Adley that Hamilton wrote around 100 million words or the equivalent of 1,200 average length novels, making him the most prolific author in history. He is known to have used at least 25 pen-names and created over 100 schools as well as writing many non-school stories. More than 5,000 of his stories have been identified, of which 3,100 were reprinted (Lofts & Adley 1970:170).

Style

Hamilton employed a lightly ironic voice, often studded with humorous classical references which had the effect of making the stories both accessible and erudite. In this respect, he has been compared to P. G. Wodehouse who emerged from a similar period and was also a prolific author in a light-hearted genre (Cadogan 1988:56). His extraordinary output has been suggested as arising from a very fluent style that came naturally to him and, in turn made the stories very readable (Cadogan 1988:1), while at the same time being somewhat wordy.

Much of his popularity derives from his ability to allow the reader to participate vicariously in the ongoing adventure. As with many later children’s writers, the stories centred on a small core group of characters who form a close knit unit – at St Jim’s there was the Terrible Three, at Rookwood the Fistical Four and at Greyfriars, The Famous Five. Such groups, while being closed to other pupils, are implicitly open to readers who are subliminally invited to include themselves amongst their number, thereby establishing their involvement with the story.

A moral message is also included within the stories. The texts are supportive of honesty, generosity, respect and discipline while being strongly against smoking and gambling, notwithstanding Hamilton’s own predilections. The message though is subtly tempered by comic characters of whom Billy Bunter is the most famous. Bunter is the antithesis of everything the stories support, being lazy, greedy, dishonest and self-centred. His presence though is tolerated by virtue of extreme incompetence and an absence of outright malice. His absurd interventions deflate the high seriousness that the authority figures seek to impose and frequently reduce their efforts to farce.

The public school setting offered an opportunity to create a world where adult presence was spread thinly, thereby giving the juvenile characters a chance to achieve something akin to independence. In such circumstances adventures could be developed which were way beyond the imagining of the readership, a formula that J.K. Rowling was to exploit with much popular success.

Criticism

Before World War 2, all of Hamilton’s writing was for weekly papers, produced on cheap paper and lacking any suggestion of permanence; it had nonetheless attracted a loyal following but unsurprisingly, no critical attention. This changed with the publication of an essay by George Orwell entitled Boys' Weeklies, which paid particular attention to Hamilton’s work. He suggested that the style was deliberately formulaic so that it could be copied by a panel of authors whom he erroneously supposed to lie behind the Frank Richards name. He also denigrated the works as outdated, snobbish and right-wing, while conceding that Billy Bunter is a ‘really first-rate character’ (Orwell 1940). Hamilton’s reply included his first public acknowledgement of himself as author and defended the wholesome nature of the stories as being appropriate for his audience (Richards 1940).

Cultural historian Geoffrey Richards has written extensively about Hamilton's work, providing many examples of prominent admirers, including John Arlott, Peter Cushing, Ted Willis and Benny Green. He claims the works recall a world which contrasts with "the birth of an age which knew all about its rights but had forgotten its responsibilities"(Richards 1991:292–295).

See also

- The Magnet

- The Gem

- Greyfriars School

- Billy Bunter

- Bessie Bunter

- Tom Merry

- Boys' Weeklies - Essay by George Orwell

References

- Beal, George (Editor) (1977), The Magnet Companion, London: Howard Baker.

- Cadogan, Mary (1988), Frank Richards - The Chap Behind The Chums, Middlesex: Viking.

- Fayne, Eric; Jenkins, Roger (1972), A History of The Magnet and The Gem, Kent: Museum Press.

- Hamilton Wright, Una; McCall (2006), The Far Side of Billy Bunter: the Biography of Charles Hamilton, London: Friars Library.

- Lofts, W.O.; Adley, D.J. (1970), The Men behind Boys' Fiction, London: Howard Baker.

- Lofts, W.O.; Adley, D.J. (1975), The World of Frank Richards, London: Howard Baker.

- McCall, Peter (1982), The Greyfriars Guide, London: Howard Baker.

- Orwell, George (1940), "Boys Weeklies", Horizon, http://ghostwolf.dyndns.org/words/authors/O/OrwellGeorge/essay/boysweeklies.html.

- Richards, Frank (1940), "Frank Richards Replies to Orwell", Horizon, http://www.friardale.co.uk/Ephemera/Newspapers/George%20Orwell_Horizon_Reply.pdf.

- Richards, Frank (1962), The Autobiography of Frank Richards, London: Skilton.

- Richards, Jeffery (1991), Happiest Days: Public Schools in English Fiction, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Turner, E.S. (1975), Boys will be Boys – 3rd edition, London: Penguin.

External links

- Friardale Hamilton material

- Magnets

- Collecting Books and Magazines Detailed article

- Greyfriars, The Magnet & Billy Bunter Facts and Figures

- Greyfriars Index Detailed listing of Hamilton material

- The Friars Club Enthusiasts’ Club

- The Magnet Detailed site about The Magnet

- Bunterzone Enthusiasts’ site

- Index of Boys Weeklies

Categories:- British writers

- English children's writers

- People from Ealing

- 20th-century British children's literature

- 1876 births

- 1961 deaths

- British boys' story papers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.