- Cologne

-

"Köln" redirects here. For other uses, see Köln (disambiguation).This article is about the German city. For other uses, see Cologne (disambiguation).

Köln

CologneCologne Cathedral at nighttime

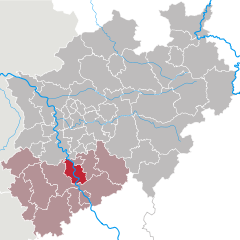

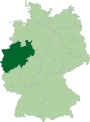

Coordinates 50°57′N 6°58′E / 50.95°N 6.96667°ECoordinates: 50°57′N 6°58′E / 50.95°N 6.96667°E Administration Country Germany State North Rhine-Westphalia Admin. region Cologne District Urban district Lord Mayor Jürgen Roters (SPD) Basic statistics Area 405.15 km2 (156.43 sq mi) Elevation 37 m (121 ft) Population 1,007,119 (31 December 2010)[1] - Density 2,486 /km2 (6,438 /sq mi) Founded 38 BC Other information Time zone CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) Licence plate K Postal codes 50441–51149 Area codes 0221, 02203 (Porz) Website www.stadt-koeln.de Cologne (English pronunciation: /kəˈloʊn/, German: Köln [kœln], Kölsch: Kölle [ˈkœɫə]) is Germany's fourth-largest city (after Berlin, Hamburg and Munich), and is the largest city both in the Germany Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia and within the Rhine-Ruhr Metropolitan Area, one of the major European metropolitan areas with more than ten million inhabitants.

Cologne is located on both sides of the Rhine River. The city's famous Cologne Cathedral (Kölner Dom) is the seat of the Catholic Archbishop of Cologne. The University of Cologne (Universität zu Köln) is one of Europe's oldest and largest universities.[2]

Cologne is a major cultural centre of the Rhineland and has a vibrant arts scene. Cologne is home to more than 30 museums and hundreds of galleries. Exhibitions range from local ancient Roman archeological sites to contemporary graphics and sculpture. The Cologne Trade Fair hosts a number of trade shows such as Art Cologne, imm Cologne, Gamescom and the Photokina.

Contents

History

Main article: History of CologneRoman Cologne

The first urban settlement on the grounds of what today is the center of Cologne was Oppidum Ubiorum, which was founded in 38 BC by the Ubii, a Cisrhenian Germanic tribe. In 50 AD, the Romans founded Colonia on the Rhine [3] and the city became the provincial capital of Germania Inferior in 85 AD.[4] The city was named "Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium" in 50 AD.[4] Considerable Roman remains can be found in present-day Cologne, especially near the wharf area, where a notable discovery of a 1900 year old Roman boat was made in late 2007.[5] From 260 to 271 Cologne was the capital of the Gallic Empire under Postumus, Marius and Victorinus. In 310 under Constantine a bridge was built over the Rhine at Cologne. The imperial governors of Rome resided in the city and became one of the most important trade and production centres in the Roman Empire north of the Alps.[3]

Maternus, who was elected as bishop in 313, was the first known bishop of Cologne. The city was the capital of a Roman province until occupied by the Franks in 459. In 785, Cologne became the seat of an archbishopric.[3]

Middle Ages

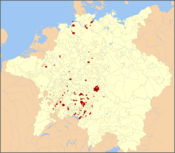

During the time of the Holy Roman Empire in the Middle Ages, the Archbishop of Cologne was one of the seven prince-electors and one of the three ecclesiastical electors. The archbishops had ruled large temporal domains but in 1288 Sigfried II von Westerburg was defeated in the Battle of Worringen and forced into exile in Bonn.

Cologne's location on the river Rhine placed it at the intersection of the major trade routes between east and west and was the basis of Cologne's growth. Cologne was a member of the Hanseatic League [3] and became a Free Imperial City in 1475. Interestingly the archbishop nevertheless preserved the right of capital punishment. Thus the municipal council (though in strict political opposition towards the archbishop) depended upon him in all matters concerning criminal justice. This included torture, which sentence was only allowed to be handed down by the episcopal judge, the so-called "Greve". This legal situation lasted until the French conquest of Cologne.

Besides its economic and political significance Cologne also became an important centre of medieval pilgrimage, when Cologne's Archbishop Rainald of Dassel gave the relics of the Three Wise Men to Cologne's cathedral in 1164 (after they in fact had been captured from Milan). Besides the three magi Cologne preserves the relics of Saint Ursula and Albertus Magnus.[6]

The economic structures of medieval and early modern Cologne were characterized by the city's status as a major harbour and transport hub upon the Rhine. Craftsmanship was organized by self-administering guilds, some of which were exclusive to women.

As a free city Cologne was a sovereign state within the Holy Roman Empire and as such had the right (and obligation) to maintain its own military force. Wearing a red uniform these troops were known as the Rote Funken (red sparks). These soldiers were part of the Army of the Holy Roman Empire ("Reichskontingent") and fought in the wars of the 17th and 18th century, including the wars against revolutionary France, when the small force was almost completely wiped out in combat. The tradition of these troops is preserved as a military persiflage by Cologne's most outstanding carnival society, the Rote Funken.[7]

The free city of Cologne must not be confused with the Archbishopric of Cologne which was a state of its own within the Holy Roman Empire. Since the second half of the 16th century the archbishops were taken from the Bavarian dynasty Wittelsbach. Due to the free status of Cologne, the archbishops were usually not allowed to enter the city. Thus they took up residence in Bonn and later in Brühl on the Rhine. As members of an influential and powerful family and supported by their outstanding status as electors, the archbishops of Cologne repeatedly challenged and threatened the free status of Cologne during the 17th and 18th century, resulting in complicated affairs, which were handled by diplomatic means and propaganda as well as by the supreme courts of the Holy Roman Empire.

From 19th century until World War II

Cologne lost its status as a free city during the French period. According to the Peace Treaty of Lunéville (1801) all the territories of the Holy Roman Empire on the left bank of the Rhine were officially incorporated into the French Republic (which already had occupied Cologne in 1798). Thus this region later became part of Napoleon's Empire. Cologne was part of the French Département Roer (named after the River Roer, German: Rur) with Aachen (French: Aix-la-Chapelle) as its capital. The French modernized public life, for example by introducing the Napoleonic code and removing the old elites from power. The Napoleonic code remained in use on the left bank of the Rhine until 1900, when a unified civil code (the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch) was introduced in the German Empire. In 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, Cologne was made part of the Kingdom of Prussia, first in the Jülich-Cleves-Berg province and then the Rhine province.

The permanent tensions between the Roman Catholic Rhineland and the overwhelmingly Protestant Prussian state repeatedly escalated with Cologne being in the focus of the conflict. In 1837 the archbishop of Cologne, Clemens August von Droste-Vischering, was arrested and imprisoned for two years after a dispute over the legal status of marriages between Protestants and Roman Catholics (Mischehenstreit). In 1874 during the Kulturkampf, Archbishop Paul Melchers was imprisoned before taking refuge in the Netherlands. These conflicts alienated the Catholic population from Berlin and contributed to a deeply felt anti-Prussian resentment, which was still significant after World War II, when the former mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, became the first West German chancellor.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Cologne absorbed numerous surrounding towns, and by World War I had already grown to 700,000 inhabitants. Industrialization changed the city and spurred its growth. Vehicle and engine manufacturing were especially successful, though heavy industry was less ubiquitous than in the Ruhr area. The cathedral, started in 1248 but abandoned around 1560, was eventually finished in 1880 not just as a place of worship but also as a German national monument celebrating the newly founded German empire and the continuity of the German nation since the Middle Ages. Some of this urban growth occurred at the expense of the city's historic heritage with much being demolished (for example, the city walls or the area around the cathedral) and sometimes replaced by present-day buildings.

Cologne was designated as one of the Fortresses of the German Confederation.[8] It was turned into a heavily armed fortress (opposing the French and Belgian fortresses of Verdun and Liège) with two fortified belts surrounding the city, the remains of which can be seen to this day.[9] The military demands on what became Germany's largest fortress presented a significant obstacle to urban development, with forts, bunkers and wide defensive dugouts completely encircling the city and preventing expansion; this resulted in a very dense built-up area within the city itself.

During World War I Cologne was the target of several only minor air raids and survived the hostilities without significant damage. Until 1926 Cologne was occupied by the British Army of the Rhine under the terms of the armistice and the subsequent Versailles Peace Treaty.[10] Contrary to the harsh measures taken by French occupation troops, the British acted with more tact towards the local population. The mayor of Cologne from 1917 until 1933 and future West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer acknowledged the political impact of this approach, especially that the British had opposed French plans for a permanent Allied occupation of the Rhineland.

As part of the de-militarization of the Rhineland the fortifications had to be dismantled. This was taken as an opportunity to create two green belts (Grüngürtel) around the city by converting the fortifications and their clear fields of fire into large public parks. However this project was not completed until 1933. In 1919 the University of Cologne, closed by the French in 1798, was refounded. This re-foundation was considered a replacement for the loss of the German University of Strasbourg that became part of France with the rest of Alsace. Cologne prospered during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and progress was made especially in respect to public governance, city planning, housing and social affairs. Social housing projects were considered exemplary and copied by other German cities. As Cologne competed for hosting the Olympics a modern sports stadium was erected at Müngersdorf. When the British occupation ended, civil aviation was allowed once again and Cologne Butzweilerhof Airport soon became a hub for national and international air traffic: second in Germany only to Berlin Tempelhof Airport.

The democratic parties lost the local elections in Cologne in March 1933 to the NSDAP and other right wing parties. Thereafter Communist as well as Social Democrats members of the city assembly were imprisoned and Mayor Adenauer was dismissed by the new holders of power. However, compared to other major cities, the Nazis never gained decisive support in Cologne and the number of votes cast for the Nazi Party in Reichstag elections was always below the national average.[11][12] By 1939 the population had risen to 772,221 inhabitants.

World War II

During World War II, Cologne was a Military Area Command Headquarters (Militärbereichshauptkommandoquartier) for the Military District (Wehrkreis) VI of Münster. Cologne was under the command of Lieutenant-General Freiherr Roeder von Diersburg, who was responsible for military operations in Bonn, Siegburg, Aachen, Jülich, Düren, and Monschau. Cologne was home to the 211th Infantry Regiment and the 26th Artillery Regiment.

During the Bombing of Cologne in World War II, Cologne endured 262 air raids[13] by the Western Allies, which caused approximately 20,000 civilian casualties and almost completely wiped out the centre of the city. During the night of 31 May 1942, Cologne was the target of "Operation Millennium", the first 1,000 bomber raid by the Royal Air Force in World War II. 1,046 heavy bombers attacked their target with 1,455 tons of explosives, approximately two-thirds of which were incendiary.[14] This raid lasted about 75 minutes, destroyed 600 acres (243 ha) of built-up area, killed 486 civilians and made 59,000 people homeless. By the end of the war, the population of Cologne had been reduced by 95%. This loss was mainly caused by a massive evacuation of the people to more rural areas. The same happened in many other German cities in the last two years of war. At the end of 1945, the population had already risen to about 500,000 again.

By that time, essentially all of Cologne's pre-war Jewish population of 11,000 had been deported or killed by the Nazis.[15] The six synagogues of the city were destroyed. The synagogue on Roonstraße was rebuilt in 1959.[16]

The outskirts of Cologne were reached by US-troops on 4 March 1945. The inner city at the left bank of the Rhine was captured on 6 March 1945 in half a day, meeting minor resistance only. Because the Hohenzollernbrücke was destroyed on retreat by German pioneers, the boroughs at the right bank of the river remained under German control until mid of April 1945.[17]

Post-war Cologne until today

Despite Cologne's status of being the largest city in the region, nearby Düsseldorf was chosen as the political capital of the federated state of North Rhine-Westphalia. With Bonn being chosen as the provisional capital (provisorische Bundeshauptstadt) and seat of the government of the Federal Republic of Germany (then informally West Germany), Cologne benefited by being sandwiched between two important political centres. The city became and still is home to a number of Federal agencies and organizations. After reunification in 1990, Berlin was made the capital of Germany.

In 1945 architect and urban planner Rudolf Schwarz called Cologne the "world's greatest heap of rubble." Schwarz designed the master plan of reconstruction in 1947, which called for the construction of several new thoroughfares through the downtown area, especially the Nord-Süd-Fahrt ("North-South-Drive"). The master plan took into consideration the fact that even shortly after the war a large increase in automobile traffic could be anticipated. Plans for new roads had already, to a certain degree, evolved under the Nazi administration, but the actual construction became easier in times when the majority of downtown lots were undeveloped.

The destruction of 95% of the city centre including the famous Twelve Romanesque churches like St. Gereon, Great St. Martin, St. Maria im Kapitol and several other monuments in World War II meant a tremendous loss of cultural treasures. The rebuilding of those churches and other landmarks like the Gürzenich event hall was not undisputed among leading architects and art historians at that time, but in most cases, civil intention prevailed. The reconstruction lasted until the 1990s, when the Romanesque church of St. Kunibert was finished.

In 1959, the city's population reached pre-war numbers again. It then grew steadily, exceeding 1 million for about one year from 1975. It has remained just below that until mid 2010, when it exceeded 1 million again.

In the 1980s and 1990s Cologne's economy prospered for two main reasons. Firstly, a growth in the number of media companies, both in the private and public sectors; they are especially catered for in the newly-developed Media Park, which creates a strongly visual focal point in the Cologne town centre and includes the KölnTurm, one of Cologne's most prominent high-rise buildings. Secondly, a permanent improvement of the diverse traffic infrastructure made Cologne one of the most easily accessible metropolitan areas in Central Europe.

Due to the economic success of the Cologne Trade Fair, the city arranged a large extension to the fair site in 2005. At the same time the original buildings, which date back to the 1920s are rented out to RTL, Germany's largest private broadcaster, as their new corporate headquarters.

Geography

Districts

Main article: Districts of CologneCologne is subdivided into 9 districts (Stadtbezirke) and 85 city parts (Stadtteile):[18]

- Innenstadt (Stadtbezirk 1)

- Altstadt-Nord, Altstadt-Süd, Neustadt-Nord, Neustadt-Süd, Deutz

- Rodenkirchen (Stadtbezirk 2)

- Bayenthal, Godorf, Hahnwald, Immendorf, Marienburg, Meschenich, Raderberg, Raderthal, Rodenkirchen, Rondorf, Sürth, Weiß, Zollstock

- Lindenthal (Stadtbezirk 3)

- Braunsfeld, Junkersdorf, Klettenberg, Lindenthal, Lövenich, Müngersdorf, Sülz, Weiden, Widdersdorf

- Ehrenfeld (Stadtbezirk 4)

- Bickendorf, Bocklemünd/Mengenich, Ehrenfeld, Neuehrenfeld, Ossendorf, Vogelsang

- Nippes (Stadtbezirk 5)

- Bilderstöckchen, Longerich, Mauenheim, Niehl, Nippes, Riehl, Weidenpesch

- Chorweiler (Stadtbezirk 6)

- Blumenberg, Chorweiler, Esch/Auweiler, Fühlingen, Heimersdorf, Lindweiler, Merkenich, Pesch, Roggendorf/Thenhoven, Seeberg, Volkhoven/Weiler, Worringen

- Porz (Stadtbezirk 7)

- Eil, Elsdorf, Ensen, Finkenberg, Gremberghoven, Grengel, Langel, Libur, Lind, Poll, Porz, Urbach, Wahn, Wahnheide, Westhoven, Zündorf

- Kalk (Stadtbezirk 8)

- Brück, Höhenberg, Humboldt/Gremberg, Kalk, Merheim, Neubrück, Ostheim, Rath/Heumar, Vingst

- Mülheim (Stadtbezirk 9)

- Buchforst, Buchheim, Dellbrück, Dünnwald, Flittard, Höhenhaus, Holweide, Mülheim, Stammheim

Climate

Cologne is one of the warmest cities in Germany. It has a temperate–oceanic climate with relatively mild winters and warm summers. Its average annual temperature is 10 °C (50 °F): 14.5 °C (58 °F) during the day and 5.5 °C (42 °F) at night.

Climate data for Cologne Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Average high °C (°F) 5.2

(41.4)6.6

(43.9)10.5

(50.9)14.2

(57.6)19.0

(66.2)21.3

(70.3)23.7

(74.7)23.7

(74.7)19.6

(67.3)14.6

(58.3)9.0

(48.2)6.2

(43.2)14.5 Daily mean °C (°F) 2.3

(36.1)2.9

(37.2)6.1

(43.0)8.9

(48.0)13.4

(56.1)16.0

(60.8)18.3

(64.9)18.0

(64.4)14.6

(58.3)10.4

(50.7)5.8

(42.4)3.4

(38.1)10.0 Average low °C (°F) −0.7

(30.7)−0.9

(30.4)1.7

(35.1)3.6

(38.5)7.7

(45.9)10.7

(51.3)12.8

(55.0)12.3

(54.1)9.6

(49.3)6.2

(43.2)2.5

(36.5)0.6

(33.1)5.5 Precipitation mm (inches) 60.4

(2.378)46.6

(1.835)62.5

(2.461)50.5

(1.988)72.4

(2.85)87.6

(3.449)86.0

(3.386)65.3

(2.571)69.3

(2.728)61.7

(2.429)63.2

(2.488)70.7

(2.783)796.2

(31.346)Avg. precipitation days 11.9 9.3 12.5 10.2 10.4 11.6 11.2 9.4 10.7 10.5 11.9 12.9 120.9 Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN)[19] Flood protection

Cologne is regularly affected by flooding from the Rhine and is considered the most flood-prone European city.[20] A city agency (Stadtentwässerungsbetriebe Köln,[21] "Cologne Urban Drainage Operations") manages an extensive flood control system which includes both permanent and mobile flood walls, protection from rising waters for buildings close to the river banks, monitoring and forecasting systems, pumping stations and programs to create or protect floodplains and river embankments.[20][22] The system was redesigned after a 1993 flood which resulted in heavy damages.[20]

Demographics

Main article: Demographics of CologneCologne is the fourth-largest city in Germany in terms of inhabitants after Berlin, Hamburg and Munich. As of 30 June 2011, there were officially 1,010,269 residents.[23] Cologne is the centre of the Cologne/Bonn Region with around 3 million inhabitants (including the neighboring cities of Bonn, Hürth, Leverkusen, and Bergisch Gladbach).

According to local statistics, in 2006 the population density in the city was 2,528 inhabitants per square kilometre. 31.4 percent of the population has migrated there, and 17.2 percent of Cologne's population is non-German. The largest group, comprising 6.3 percent of the total population, is Turkish.[24] As of September 2007, there are about 120,000 Muslims living in Cologne, mostly of Turkish origin.[25] Cologne also has the oldest and one of the largest Jewish communities in Germany.[26]

In the city the population was spread out with 15.5% under the age of 18, 67.0% from 18 to 64 and 17.4% who were 65 years of age or older.[27]

Government

See also: Cologne City HallThe city's administration is headed by the mayor and the three deputy mayors. Jürgen Roters of the Social Democratic Party has been mayor since 20 October 2009.[28]

Political traditions and developments

The long tradition of a free imperial city, which long dominated exclusively Catholic population and the age-old conflict between the church and the bourgeoisie (and within it between the patricians and craftsmen) has created its own political climate in Cologne. Various interest groups often form the basis of societal socialization and therefore beyond party boundaries. The resulting network of relationships, the political, economic and cultural links with each other in a system of mutual favors, obligations and dependencies, also called Cologne coterie. This has often led to an unusual proportional distribution in the city government and degenerated at times into corruption: in 1999, revealed "waste scandal" over kickbacks and illegal campaign contributions, not only the entrepreneur Hellmut Trienekens in prison brought, but did throw almost the entire leadership staff of the ruling Social Democrats.

The city was connected because of their Catholic tradition in the Empire and the Weimar Republic established the center, joined soon after the war, the political majority of the CDU to the SPD. This ruled for 40 years, in part, by an absolute majority of Council. Because of liberal traditions Cologne was always a stronghold of the FDP, because of its tolerant social climate and the Greens. Both parties do - with varying degrees of success - the increasingly popular parties disputed the majority.

Mayor

Lord Mayor of Cologne is Jürgen Roters of the Social Democratic Party. As a common candidate of the SPD and the Greens, he received 54.67% of the vote on 30 August 2009 at the municipal election. He has been Lord Mayor since 21 October 2009.

Elections

City Councillors are set to a five year term and the Mayor has a six year term.[29]

Make-up of city council

Party Seats Source Social Democratic Party 25 [30] Christian Democratic Union 25 Green Party 20 Free Democratic Party 9 pro Cologne 5 The Left 4 Free Voters 1 DEINE FREUNDE 1 Cityscape

Panoramic view of the city centre at night as seen from Deutz; from left to right: Deutz Bridge, Great St. Martin Church, Cologne Cathedral, Hohenzollern Bridge

The inner city of Cologne was completely destroyed during World War II. The reconstruction of the city followed the style of the 1950s, while respecting the old layout and naming of the streets. Thus, the city today is characterized by simple and modest post-war buildings, with few interspersed pre-war buildings which were reconstructed due to their historical importance. Some buildings of the "Wiederaufbauzeit" (era of reconstruction), for example the opera house by Wilhelm Riphahn, are nowadays regarded as classics of modern architecture.[citation needed] Nevertheless, the uncompromising style of the Cologne Opera house and other modern buildings has remained controversial.

Green areas account for over a quarter of Cologne which is approximately 75 m2 (807.29 sq ft) of public green space for every citizen of the city.[31]

Tourism

Cologne had 4.31 million overnight accommodations booked and 2.38 million arrivals in 2008.[18] The city also has the most pubs per capita in Germany.[32] The city has 70 clubs and other party spots. The city has "countless" bars, restaurants and pubs.[32]

Landmarks

Churches

- Cologne Cathedral (German: Kölner Dom) is the city's most famous monument and the Cologne residents' most respected landmark. It is a Gothic church, started in 1248, and completed in 1880. In 1996, it was designated a World Heritage site; it houses the Shrine of the Three Kings that supposedly contains the relics of the Three Magi (see also[33]). Residents of Cologne sometimes refer to the cathedral as "the eternal construction site" (Dauerbaustelle).

- Twelve Romanesque churches: These buildings are outstanding examples of medieval church architecture. The origins of some of the churches go back as far as Roman times, for example St. Gereon, which was originally a chapel in a Roman graveyard. With the exception of St. Maria Lyskirchen all of these churches were very badly damaged during World War II. Reconstruction was only finished in the 1990s.

Medieval houses

The Cologne City Hall (Kölner Rathaus), established in the 12th century, is the oldest city hall in Germany still in use.[34] The Renaissance style loggia and tower were added in the 15th century. Other famous houses include the Gürzenich, Haus Saaleck and the Overstolzenhaus.

Medieval city gates

Of the once 12 medieval city gates, only the Eigelsteintorburg at Ebertplatz, the Hahnentor at Rudolfplatz and the Severinstorburg at Chlodwigplatz still stand today.

Streets

Main article: Streets in Cologne- The Cologne Ring boulevards (such as Hohenzollernring, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Ring, Hansaring) with their medieval city gates (such as Hahnentorburg on Rudolfplatz) are also known for their night life.

- Hohe Straße (literally: High Street) is one of the main shopping areas and extends past the cathedral in an approximately southerly direction. The street contains many gift shops, clothing stores, fast food restaurants and electronic goods dealers.

- Schildergasse - connects the Neumarkt plaza on its west end to the southern end of the Hohe Strasse shopping street at its east end and has been named the busiest shopping street in Europe with 13,000 people passing through every hour.

- Ehrenstraße - the shopping area around Apostelnstrasse, Ehrenstrasse, and Rudolfplatz is a little more on the eccentric and stylish side.

Bridges

Several bridges cross the Rhine in Cologne. They are (from South to North): the Cologne Rodenkirchen Bridge, Southern Railway Bridge, Severin Bridge, Deutz Bridge, Hohenzollern Bridge, Zoo Bridge (Zoobrücke) and Cologne Mülheim Bridge. In particular the iron tied arch Hohenzollern Bridge (Hohenzollernbrücke) is a dominant landmark along the river embankment. A Rhine river crossing of a special kind is provided by the Cologne Cable Car (German: Kölner Seilbahn), a cableway that runs across the Rhine between the Cologne Zoological Garden in Niehl and the Rheinpark in Deutz.

High rise structures

Cologne's tallest structure is the Colonius telecommunication tower at 266 m/873 ft. The observation deck has been closed since 1992. A selection of the tallest buildings in Cologne are listed below. Other tall structures include the Hansahochhaus (designed by architect Jacob Koerfer and completed in 1925 - it was at one time Europe's tallest office building), the Kranhaus buildings at Rheinauhafen and the Messeturm Köln (English: Trade Fair tower).

Skyscraper Image Height in metres Floors Year Address Notes KölnTurm

148.5 43 2001 Mediapark 8, Neustadt-Nord (literally: Cologne Tower), Cologne's second tallest building at 165.48 metres (542.91 ft) in height, second only to the Colonius telecommunication tower. The 30th floor of the building has a restaurant and a terrace with 360° views of the city. Colonia-Hochhaus

147 45 1973 An der Schanz 2, Riehl tallest building in Germany from 1973 to 1976. Today, it is still the country's tallest residential building. Rheintower

138 34 1980 Raderberggürtel, Marienburg former headquarters of Deutsche Welle, since 2007 under renovation with the new name Rheintower Köln-Marienburg. Uni-Center[35]

133 45 1973 Luxemburger Straße, Sülz TÜV Rheinland

112 22 1974 Am Grauen Stein, Poll KölnTriangle

103 29 2006 Ottoplatz 1, Deutz opposite to the cathedral with a 103 m (338 ft) high viewing platform and a view of the cathedral over the Rhine; headquarters of the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Herkules-Hochhaus

102 31 1969 Graeffstraße 1, Ehrenfeld Culture

Cologne has several museums. The famous Roman-Germanic Museum features art and architecture from the city's distant past; the Museum Ludwig houses one of the most important collections of modern art in Europe, including a Picasso collection matched only by the museums in Barcelona and Paris. The Schnütgen Museum of religious art is housed in St. Cecilia, one of Cologne's Twelve Romanesque churches. Several orchestras are active in the city, among them the Gürzenich Orchestra and the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne, both based at the Cologne Philharmonic Orchestra Building.[36] Other orchestras are the Musica Antiqua Köln, as well as several choirs, including the WDR Rundfunkchor Köln. Cologne was also an important centre of electronic music in the 1950s (Studio für elektronische Musik, Karlheinz Stockhausen) and again from the 90s onward. The public radio and TV station WDR was involved in promoting musical movements such as Krautrock in the 70s; the influential Can was formed there in 1968. There are several centres of nightlife, among them the Kwartier Latäng (the student quarter around the Zülpicher Straße) and the nightclub-studded areas around Hohenzollernring, Friesenplatz and Rudolfplatz.

The large annual literary festival Lit.Cologne features regional and international authors. The main literary figure connected with Cologne is writer Heinrich Böll, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Cologne is well known for its beer, called Kölsch. Kölsch is also the name of the local dialect. This has led to the common joke of Kölsch being the only language one can drink.

Cologne is also famous for Eau de Cologne (German: Kölnisch Wasser; lit: Water of Cologne), a perfume created by Italian expatriate Johann Maria Farina at the beginning of the 18th century. During the 18th century this perfume became increasingly popular, was exported all over Europe by the Farina family and Farina became a household name for Eau de Cologne. In 1803 Wilhelm Mülhens entered into a contract with an unrelated person from Italy named Carlo Francesco Farina who granted him the right to use his family name and Mühlens opened a small factory at Cologne's Glockengasse. In later years and after various court battles his grandson Ferdinand Mülhens had to abandon the name Farina for the company and their product. He decided to use the house number given to the factory at Glockengasse during French occupation in the early 19th century: 4711. Today, original Eau de Cologne is still produced in Cologne by both the Farina family, currently in the eighth generation, and by Mäurer and Wirtz who bought the 4711 brand in 2006.

Carnival

The Cologne carnival is one of the biggest street festivals in Europe. In Cologne, the carnival season officially starts on 11 November at 11 minutes past 11 a.m. with the proclamation of the new Carnival Season, and continues until Ash Wednesday. But the so-called "Tolle Tage" (crazy days) don't start until Weiberfastnacht (Women's Carnival) or, in dialect, Wieverfastelovend (Thursday before Ash Wednesday), which is the beginning of the street carnival. Zülpicher Strasse and its surroundings, Neumarkt square, Heumarkt and all bars and pubs in the city are crowded with people in costumes dancing and drinking on the streets. Hundreds of thousands of visitors flock to Cologne during this time. Generally, around a million people celebrate in the streets on the Thursday before Ash Wednesday.[37]

Rivalry with Düsseldorf

Cologne and Düsseldorf have a "fierce regional rivalry".[38], which includes carnival parades, football, and beer.[38] People in Cologne prefer Kölsch while people in Düsseldorf prefer Alt.[38] Waiters and patrons will "scorn" and make a "mockery" of people who order Alt beer in Cologne and Kölsch in Düsseldorf.[38] The rivalry has been described as a "love-hate relationship".[38]

Museums

Main article: List of museums in Cologne- Farina Fragrance Museum, the birthplace of Eau de Cologne.

- Römisch-Germanisches Museum (English: Roman-Germanic Museum) for ancient Roman and Germanic culture.

- Wallraf-Richartz Museum for European painting from the 13th to the early 20th century.

- Museum Ludwig for modern art.

- Museum Schnütgen for medieval art.

- Museum für Angewandte Kunst for applied art.

- Kolumba Kunstmuseum des Erzbistums Köln (Art museum of the archbishopric of Cologne), modern art museum built around medieval ruins, completed 2007.

- Cathedral Treasury "Domschatzkammer" in the historic underground vaults of the Cathedral

- EL-DE Haus, the former local headquarters of the Gestapo houses a museum documenting Nazi rule in Cologne with a special focus on the persecution of political dissenters and minorities.

- German Sports and Olympic Museum, with exhibitions about sports from antiquity until the present.

- Chocolate Museum, officially called Imhoff-Schokoladenmuseum.

- Forum for Internet Technology in Contemporary Art - collections of Internet based art, corporate part of (NewMediaArtProjectNetwork):cologne - the experimental platform for art and New Media.

- Flora und Botanischer Garten Köln, the city's formal park and main botanical garden

- Forstbotanischer Garten Köln, an arboretum and woodland botanical garden

Music fairs and festivals

The city was home to the internationally famous Ringfest, and now to the C/o pop festival.[39]

Economy

North entrance to Koelnmesse, 2008

North entrance to Koelnmesse, 2008

As the largest city in the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region, Cologne benefits from a large market structure.[40] In competition for location factors with Düsseldorf, the economy of Cologne is primarily based on insurance and media industries,[41] while the city is also an important cultural and research centre and home to a number of corporate headquarters.

Among the largest media companies based in Cologne are Westdeutscher Rundfunk, RTL Television (with subsidiaries), n-tv, Deutschlandradio, Brainpool TV and publishing houses like J. P. Bachem, Taschen, Tandem Verlag and M. DuMont Schauberg. Several clusters of media, arts and communications agencies, TV production studios, and state agencies work partly with private and government funded cultural instititutions. Among the insurance companies based in Cologne are Central, DEVK, DKV, Generali Deutschland, Gothaer, HDI Gerling and national headquarters of AXA Insurance and Zurich Financial Services.

Lufthansa, the German flag carrier, and Lufthansa CityLine have their main corporate headquarters in Cologne.[42] Largest employer in Cologne is Ford Europe, which has its European headquarters and a factory in Niehl (Ford-Werke GmbH).[43] Toyota Motorsport GmbH (TMG), Toyota's official motorsports team, responsible for Toyota rally cars, and then Formula One cars has headquarters and workshops in Cologne. Other large companies based in Cologne include the REWE Group, TÜV Rheinland, Deutz AG and a number of Kölsch breweries. Cologne has the country's highest density of pubs per capita.[32] The three largest Kölsch breweries are Reissdorf, Gaffel and Früh.

brewery established annual output in hectolitre Heinrich Reissdorf 1894 650.000 Gaffel Becker & Co 1908 500.000 Cölner Hofbräu Früh 1904 440.000 Historically, Cologne has always been an important trade city, with land, air, and sea connections.[2] The city has five Rhine ports,[2] the second largest inland port in Germany and one of the largest in Europe. Cologne-Bonn Airport is the second largest freight terminal in Germany.[2] Today, the Cologne trade fair (Koelnmesse) ranks as a major European trade fair location with over 50 trade fairs[2] and other large cultural and sports events. In 2008, Cologne had 4.31 million overnight accommodations booked and 2.38 million arrivals.[18] Cologne's largest daily newspaper is the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger.

Transport

Main article: Transport in CologneRoad transport

Road building had been a major issue in the 1920s under the leadership of mayor Konrad Adenauer. The first German limited access road was constructed after 1929 between Cologne and Bonn. Today, this is the Bundesautobahn 555. In 1965, Cologne became the first German city to be fully encircled by a freeway belt. Roughly at the same time a downtown bypass freeway (Stadtautobahn) was planned, but only partially put into effect, due to opposition by environmental groups. The completed section became Bundesstraße ("Federal Road") B 55a which begins at the Zoobrücke ("Zoo Bridge") and meets with A 4 and A 3 at the interchange Cologne East. Nevertheless, it is referred to as Stadtautobahn by most locals. In contrast to this the Nord-Süd-Fahrt ("North-South-Drive") was actually completed, a new four/six lane downtown thoroughfare, which had already been anticipated by planners like Fritz Schumacher in the 1920s. The last section south of Ebertplatz was completed in 1972.

In 2005, the first stretch of an eight-lane freeway in North Rhine-Westphalia was opened to traffic on Bundesautobahn 3, part of the eastern section of the Cologne Beltway between the interchanges Cologne East and Heumar.

Cycling

Cologne Stadtbahn at Bensberg station

Cologne Stadtbahn at Bensberg station

Train at Köln Hbf (Cologne Central Station)

Train at Köln Hbf (Cologne Central Station)

Like most German cities, Cologne has a traffic layout designed to be bicycle-friendly. There is an extensive cycle network, featuring pavement-edge cycle lanes linked by cycle priority crossings. In some of the narrow one-way central streets, cyclists are explicitly allowed to cycle both ways.

Rail transport

Cologne has a railway service with Deutsche Bahn Intercity and ICE-trains stopping at Köln Hauptbahnhof (Cologne Central Station), Köln Messe/Deutz and Cologne/Bonn Airport. ICE and TGV Thalys high-speed trains link Cologne with Amsterdam, Brussels (in 1h47, 6 departures/day) and Paris (in 3h14, 6 departures/day). There are frequent ICE trains to other German cities, including Frankfurt am Main and Berlin. ICE Trains to London via the Channel Tunnel are planned for 2013.[44]

The Cologne city railway operated by Kölner Verkehrsbetriebe (KVB)[45] is an extensive light rail system that is partially underground (referred to as U-Bahn) and serves Cologne and a number of neighboring cities. Nearby Bonn is linked by both the city railway and Deutsche Bahn trains, and occasional recreational boats on the Rhine. Düsseldorf is also linked by S-Bahn trains which are operated by Deutsche Bahn.

There are also frequent buses covering most of the city and surrounding suburbs, and Eurolines coaches to London via Brussels.

Water transport

Häfen und Güterverkehr Köln (Cologne Ports and Railways) (HGK) is one of the largest operators for inland ports in Germany.[46] Ports include Köln-Deutz, Köln-Godorf and Köln-Niehl I and II. Köln-Düsseldorfer offers Rhine river cruises along the entire Rhine.

Air transport

Cologne's international airport is Cologne/Bonn Airport (CGN). It is also called Konrad Adenauer Airport after Germany's first post-war Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who was born in the city and was mayor of Cologne from 1917 until 1933. The airport is shared with the neighbouring city of Bonn. Cologne is headquarter to the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). The airport is also the main hub of the airline Germanwings.

Education

Cologne is home to numerous universities and colleges,[47][48] and host to some 72,000 students.[2] Its oldest university, the University of Cologne (originally founded in 1388[3]) is the largest university in Germany, as the Cologne University of Applied Sciences is the largest university of Applied Sciences in the country. The Cologne University of Music and Dance is the largest conservatory in Europe.[49]

- Public and state universities:

- University of Cologne (Universität zu Köln);

- German Sport University Cologne (Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln).

- Public and state colleges:

- Cologne University of Applied Sciences (Fachhochschule Köln);

- Köln International School of Design;

- Cologne University of Music and Dance (Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln);

- Academy of Media Arts Cologne (Kunsthochschule für Medien Köln);

- Private colleges:

- Catholic University of Applied Sciences (Katholische Hochschule Nordrhein-Westfalen);

- Cologne Business School;

- international filmschool cologne (internationale filmschule köln);

- Rhenish University of Applied Sciences (Rheinische Fachhochschule Köln)

- Research institutes:

- German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt);

- European Astronaut Center (EAC) of the European Space Agency;

- European College of Sport Science (ECSS);

- Max Planck Institute for the Biology of Ageing (Max-Planck-Institut für die Biologie des Alterns);

- Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung);

- Max Planck Institute for Neurological Research (Max-Planck-Institut für neurologische Forschung);

- Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research (Max-Planck-Institut für Züchtungsforschung).

Former colleges include:

- The Cologne Art and Crafts Schools (Kölner Werkschulen);

- The Cologne Institute for Religious Art (Kölner Institut für religiöse Kunst)

Media

Within Germany, Cologne is known as an important media centre. Several radio and television stations, including Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), RTL and VOX, have their headquarters in the city. Film and TV production is also important. The city is "Germany's capital of TV crime stories".[50] A third of all German TV productions are produced in the Cologne region.[50] Further, the city hosts the Cologne Comedy Festival, which is considered to be the largest comedy festival in mainland Europe.[51]

Sports

Cologne hosts Bundesliga club 1. FC Köln.[52] 1. FC Köln plays its home matches in RheinEnergieStadion which also hosted 5 matches of the 2006 FIFA World Cup.[53] The International Olympic Committee and Internationale Vereinigung Sport- und Freizeiteinrichtungen e.V. gave RheinEnergieStadion a bronze medal for "being one of the best sporting venues in the world".[53]

The city is also home of the ice hockey team Kölner Haie, in the highest ice hockey league in Germany, the Deutsche Eishockey Liga.[52] They are based at the Lanxess Arena.[52]

Several horse races per year are held at Cologne-Weidenpesch Racecourse since 1897, the annual Cologne Marathon was started in 1997. From 2002-2009, the Panasonic Toyota Racing Formula One team was based in the Marsdorf suburb, at the Toyota Motorsport GmbH facility.

Cologne is considered "the secret golf capital of Germany".[52] The first golf club in North Rhine-Westphalia was founded in Cologne in 1906.[52] The city offers the most options and top events in Germany.[52]

The city has hosted several athletic events which includes the 2005 FIFA Confederations Cup, 2006 FIFA World Cup, 2007 World Men's Handball Championship, 2010 IIHF World Championship and 2010 Gay Games.[4]

Twin towns — sister cities

Cologne is "twinned" with the following cities:[54]

Turku, Finland, since 1967

Turku, Finland, since 1967 Neukölln, Germany, since 1967

Neukölln, Germany, since 1967 Tel Aviv, Israel, since 1979

Tel Aviv, Israel, since 1979 Barcelona, Spain, since 1984[56]

Barcelona, Spain, since 1984[56] Beijing, China, since 1987[57]

Beijing, China, since 1987[57] Cork, Ireland, since 1988

Cork, Ireland, since 1988 Thessaloniki, Greece, since 1988[58]

Thessaloniki, Greece, since 1988[58] Corinto/El Realejo, Nicaragua, since 1988

Corinto/El Realejo, Nicaragua, since 1988 Indianapolis, United States, since 1988

Indianapolis, United States, since 1988

Volgograd, Russia, since 1988

Volgograd, Russia, since 1988 Treptow-Köpenick, Germany, since 1990

Treptow-Köpenick, Germany, since 1990 Katowice, Poland, since 1991

Katowice, Poland, since 1991 Bethlehem, Palestinian Territories, since 1996[59]

Bethlehem, Palestinian Territories, since 1996[59] Istanbul, Turkey, since 1997

Istanbul, Turkey, since 1997 Cluj-Napoca, Romania, since 1999

Cluj-Napoca, Romania, since 1999 Batangas, Philippines

Batangas, Philippines Saskatoon, Canada

Saskatoon, Canada Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, since 2011

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, since 2011

Additionally, the districts of Rodenkirchen, Lindenthal and Porz continue to maintain individual town-partnerships, established during their time as independent municipalities.

Born in Cologne

Notable people, whose roots can be found in Cologne:

- Adenauer, Konrad (5 January 1876 - 19 April 1967), politician, mayor of Cologne (1917–1933, 1945) and first West German Federal Chancellor

- Agrippa, Heinrich Cornelius (1486–1535), alchemist, occultist, and author of Three Books of Occult Philosophy

- Agrippina the Younger (6 November 15 - between 19 March and 23 March 59), Roman Empress (wife of Emperor Claudius) and mother of Emperor Nero

- Birnbaum, Heinrich (1403–1473), a Catholic monk

- Blum, Robert (10 November 1807 - 9 November 1848), politician and martyr of the 19th century democratic movement in Germany

- Böll, Heinrich (21 December 1917 - 16 July 1985), writer and winner of the Nobel prize for literature in 1972

- Bruch, Max (6 January 1838 - 2 October 1920) composer

- Calatrava, Álex (born 14 June 1973), Spanish professional tennis player

- Donnersmarck, Florian Henckel von (born 2 May 1973), Academy Award-winning director and screenwriter

- Ernst, Max (2 April 1891 - 1 April 1976), artist

- Gossow, Angela (5 November 1974) The lead vocalist of the Swedish melodic death metal band Arch Enemy

- Heidemann, Britta (born 22 December 1982), épée fencer and Olympic medalist

- Herr, Trude (4 May 1927 - 16 March 1991), actress and singer

- Höner, Stefanie (born 2 August 1969), actress

- Kier, Udo (born 14 October 1944), actor

- Jutta Kleinschmidt (born August 29, 1962), offroad automotive racing competitor

- Klemperer, Werner (22 March 1920 - 6 December 2000), Emmy Award-winning comedy actor

- Klibansky, Erich (28 November 1900 - 24 July 1942), Jewish headmaster and teacher

- Kober, Adolf (3 September 1870 - 30 December 1958), Jewish rabbi and medievalist

- Krekel, Hildegard (born 2 June 1952), actress

- Krekel, Lotti (born 23 August 1941), actress and singer

- Krupp, Uwe (born 24 June 1965), professional (ice) hockey player

- Kühn, Heinz (18 February 1912 - 12 March 1992), Minister-President of North Rhine-Westphalia (1966–1978)

- Lauterbach, Heiner (born 10 April 1953), actor

- Liebert, Ottmar (born 1 February 1961), musician

- Millowitsch, Marie-Luise (born 23 November 1955), actress

- Millowitsch, Peter (born 1 February 1949), actor, playwright and theatre director

- Millowitsch, Willy (8 January 1909 - 20 September 1999), actor, playwright and theatre director

- Niedecken, Wolfgang (born 30 March 1951), singer, musician, artist and bandleader of BAP

- Neuhoff, Theodor von (25 August 1694 - 11 December 1756), briefly King Theodore of Corsica

- Offenbach, Jacques (20 June 1819 - 5 October 1880), composer

- Ostermann, Wilhelm (1 October 1876 - 6 August 1936) composer

- Petras, Kim (born 27 August 1992), singer

- Prausnitz, Frederik William (26 August 1920 - 12 November 2004), American conductor and teacher

- Päffgen, Christa aka Nico (16 October 1938 - 18 July 1988), model, actress, singer and songwriter (see Velvet Underground) and Warhol Superstar

- Raab, Stefan (born 20 October 1966), German entertainer and host of ESC 2011

- Rüttgers, Jürgen (born 26 June 1951), Minister-President of North Rhine-Westphalia 2005-2010

- Stockhausen, Markus (born 2 May 1957), musician and composer

- Trips, Wolfgang Graf Berghe von, Formula One racing driver

- Vondel, Joost van den (17 November 1587 - 5 February 1679), Dutch poet and playwright

- Weimar, Robert (born 13 May 1932), legal scientist and psychologist

See also

- Stadtwerke Köln, the municipal infrastructure company, operator of the city's railways, ports and utilities.

- History of the Jews in Cologne

References

- ^ "Amtliche Bevölkerungszahlen" (in German). Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW. 31 December 2010. http://www.it.nrw.de/statistik/a/daten/amtlichebevoelkerungszahlen/index.html.

- ^ a b c d e f "Economy". KölnTourismus. http://www.koeln.de/cologne_tourist_information/economy. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "From Ubii village to metropolis". City of Cologne. http://www.koeln.de/cologne_tourist_information/history/from_ubii_village_metropolis. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ a b c "Facts and figures". City of Cologne. http://www.koeln.de/cologne_tourist_information/history/facts_and_figures. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "C.Michael Hogan, ''Cologne Wharf'', The Megalithic Portal, editor Andy Burnham, 2007". Megalithic.co.uk. http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=18208. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ Joseph P. Huffman, Family, Commerce, and Religion in London and Cologne (1998) covers from 1000 to 1300.

- ^ "Rote Funken - Kölsche Funke rut-wieß vun 1823 e.V. - Rote Funken Koeln". Rote-funken.de. http://www.rote-funken.de/. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ United Services Magazine, December 1835

- ^ "Festung Köln". http://www.altearmee.de/zwischenwerk/index.htm. Retrieved April 2011.

- ^ Cologne Evacuated, TIME Magazine, February 15, 1926

- ^ "Weimarer Wahlen". Web.archive.org. 2008-02-11. Archived from the original on 2008-02-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20080211085633/http://weimarer-wahlen.de/de/index.html. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ "Voting results 1919-1933 Cologne-Aachen". Wahlen-in-deutschland.de. http://www.wahlen-in-deutschland.de/wrtwkoelnaachen.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ koelnarchitektur (2003-07-15). "on the reconstruction of Cologne". Koelnarchitektur.de. http://www.koelnarchitektur.de/pages/de/home/news_archiv/823.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ Tourtellot, Arthur B. et al. Life's Picture History of World War II, p. 237. Time Incorporated, New York, 1950.

- ^ Kirsten Serup-Bilfeld, Zwischen Dom und Davidstern. Jüdisches Leben in Köln von den Anfängen bis heute. Köln 2001, page 193

- ^ "Synagogen-Gemeinde Köln". Sgk.de. 1931-06-26. http://www.sgk.de/index.php/historie.html. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ "Trotz Durchhalteparolen wenig Widerstand - Die US-Armee nimmt Köln ein [Minor restistance despite rallying calls Durchhalteparolen wenig Widerstand - the US-army captures Cologne]" (in German). Sixty years ago [Vor 60 Jahren] on www.wdr.de. Westdeutscher Rundfunk. 7 March 2005. http://www1.wdr.de/themen/archiv/stichtag/stichtag808.html. Retrieved 29 Oktober 2011.

- ^ a b c "Cologne at a glance". City of Cologne. http://www.koeln.de/cologne_tourist_information/cologne_a_glance. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "Weather Information for Cologne". http://www.worldweather.org/016/c00056.htm.

- ^ a b c "Flood Forecasting and Flood Defence in Cologne". Mitigation of Climate Induced Natural Hazards (MITCH). http://www.hrwallingford.co.uk/Mitch/Workshop2/Papers/Gocth_Vogt.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ "Stadtentwässerungsbetriebe Köln : Flood Management". Steb-koeln.de. http://www.steb-koeln.de/management0.html?&L=1. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "Flood Defence Scheme City of Cologne". http://www.hochwasserschutz.de/en/pdf/IBS_Koeln_Rhein.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ "Information und Technik Nordrhein-Westfalen (IT.NRW) - Amtliche Bevölkerungszahlen". It.nrw.de. http://www.it.nrw.de/statistik/a/daten/amtlichebevoelkerungszahlen/index.html. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ "2007 - Einwohnerdaten im Überblick - Zahlen + Statistik - Bevölkerung - Stadt Köln". Web.archive.org. 2008-01-28. Archived from the original on 2008-01-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20080128135300/http://www.stadt-koeln.de/zahlen/bevoelkerung/artikel/04600/. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ "WDR Article of 15.08.2007". Wdr.de. http://www.wdr.de/studio/koeln/lokalzeit/hintergrund/moschee.jhtml. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ Serup-Bilfeldt, Kirsten (19 August 2005). "Cologne: Germany's Oldest Jewish Community". Deutsche Welle. http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,1684525,00.html. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ "City of Cologne -> Figures Statistics Population (german)". Web.archive.org. 2008-02-08. Archived from the original on 2008-02-08. http://web.archive.org/web/20080208023326/http://www.stadt-koeln.de/zahlen/bevoelkerung/artikel/04600/index.html. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ "Der Oberbürgermeister" (in German). http://www.stadt-koeln.de/1/oberbuergermeister/. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Wahlperiode" (in German). City of Cologne. http://www.stadt-koeln.de/1/wahlen/abisz/03612/. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Alle Ratsmitglieder" (in German). City of Cologne. http://www.stadt-koeln.de/1/stadtrat/ratsmitglieder/. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ "Green Cologne". KölnTourismus. http://www.koeln.de/cologne_tourist_information/exploring_city/green_cologne. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ a b c "Nightlife". KölnTourismus. http://www.koeln.de/cologne_tourist_information/nightlife. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "Offizielle Webseite des Kölner Doms | Bedeutende Werke". Koelner-dom.de. http://www.koelner-dom.de/index.php?id=dreikoenigenschrein. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ "Strategic Management Society - Cologne Conference - Cologne Information". Cologne.strategicmanagement.net. 2008-10-14. http://cologne.strategicmanagement.net/tuesday.php. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "Homepage of the Uni-Center". Unicenterkoeln.de. http://www.unicenterkoeln.de/site/unser_haus/index.php. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ "Kölner Philharmonie". Web.archive.org. 2007-12-11. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20071211142559/http://www.koelner-philharmonie.de/en/00_home/00_home.php?Style=eb281b060898acfab42beae0870f44f6. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ "Carnival - Cologne`s "fifth season" - Cologne Sights & Events - Stadt Köln". Web.archive.org. 2008-01-26. Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. http://web.archive.org/web/20080125230206/http://www.stadt-koeln.de/en/koelntourismus/karneval/. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ a b c d e "Giving beer a home in the Rhineland". The Local. 28 July 2011. http://www.thelocal.de/society/20110728-36597.html. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ "C/o Pop Official Website". http://www.c-o-pop.de/home.4.en.html.

- ^ stadt-koeln.de Cologne Business Guide (German) (English)

- ^ Cologne on Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ "Directory: World Airlines". Flight International: p. 107. 2007-04-03.

- ^ "(German) Über Ford - Standorte". Ford Germany. http://www.ford.de/UeberFord. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/travel/travel-news/highspeed-trains-to-link-england-and-germany-20111013-1lmq8.html

- ^ "Kölner Verkehrsbetriebe (KVB)". Kvb-koeln.de. http://www.kvb-koeln.de/. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ "Häfen und Güterverkehr Köln AG". Hgk.de. http://www.hgk.de/neu/english/contents/HGK_ports_cargo-handling-points.html. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ "Hochschulen - Wissensdurst KĂśln - Das KĂślner Wissenschaftsportal". Wissensdurst-koeln.de. http://wissensdurst-koeln.de/category/wissenschaft-forschung/hochschulen/. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ http://wissensdurst-koeln.de/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/flyer-spitzenforschung.pdf

- ^ "goethe.de". goethe.de. http://www.goethe.de/Ins/th/prj/nbc/edu/sch/enindex.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ a b "Productions "made in Cologne"". Cologne Tourism. http://www.cologne-tourism.com/city-experience/media-capital/production-made-in-cologne.html#c4883. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ "Cologne Comedy Festival website". Koeln-comedy.de. 2007-10-21. http://www.koeln-comedy.de/koelncomedy/index_en.html/. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sport and relaxation". KölnTourismus. http://www.koeln.de/cologne_tourist_information/exploring_city/sport_and_relaxation. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ a b "The RheinEnergie Stadium". 1. FC Köln. http://www.fc-koeln.de/en/club/stadium/. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Partnerstädte". http://www.koeln.de/koeln/die_domstadt/partnerstaedte. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Kyoto City Web / Data Box / Sister Cities". www.city.kyoto.jp. http://www.city.kyoto.jp/koho/eng/databox/sister.html. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ^ "Barcelona internacional - Ciutats agermanades" (in Spanish). © 2006-2009 Ajuntament de Barcelona. http://w3.bcn.es/XMLServeis/XMLHomeLinkPl/0,4022,229724149_257215678_1,00.html. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ^ "Sister Cities". Beijing Municipal Government. http://www.ebeijing.gov.cn/Sister_Cities/Sister_City/. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ "Twinning Cities". City of Thessaloniki. http://www.thessalonikicity.gr/English/twinning-cities.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "::Bethlehem Municipality::". www.bethlehem-city.org. http://www.bethlehem-city.org/Twining.php. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

External links

- www.cologne-tourism.com (German) (English) (Spanish) (French)

- Cologne Tourism at koeln.de (German) (English)

- City of Cologne, official City of Cologne page (German)

- Colonipedia, the city-wiki of Cologne (German)

- KölnWiki, the city-wiki of Cologne (German)

- Colonia 3D, a reconstruction of Roman Cologne

- Cologne travel guide from Wikitravel

Neuss Düsseldorf Wuppertal

Aachen

Siegen  Cologne

Cologne

Brühl Bonn Koblenz Districts of Cologne I. Innenstadt · II. Rodenkirchen · III. Lindenthal · IV. Ehrenfeld · V. Nippes · VI. Chorweiler · VII. Porz · VIII. Kalk · IX. Mülheim

Urban and rural districts in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany

Urban and rural districts in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany

Urban districts Bielefeld · Bochum · Bonn · Bottrop · Dortmund · Duisburg · Düsseldorf · Essen · Gelsenkirchen · Hagen · Hamm · Herne · Köln (Cologne) · Krefeld · Leverkusen · Mönchengladbach · Mülheim · Münster · Oberhausen · Remscheid · Solingen · Wuppertal

Rural districts Aachen · Borken · Coesfeld · Düren · Ennepe-Ruhr-Kreis · Euskirchen · Gütersloh · Heinsberg · Herford · Hochsauerlandkreis · Höxter · Kleve (Cleves) · Lippe · Märkischer Kreis · Mettmann · Minden-Lübbecke · Oberbergischer Kreis · Olpe · Paderborn · Recklinghausen · Rheinisch-Bergischer Kreis · Rhein-Erft-Kreis · Rhein-Kreis Neuss · Rhein-Sieg-Kreis · Siegen-Wittgenstein · Soest · Steinfurt · Unna · Viersen · Warendorf · WeselCities in Germany by population 1,000,000+ 500,000+ 200,000+ Aachen · Augsburg · Bielefeld · Bochum · Bonn · Braunschweig · Chemnitz · Duisburg · Erfurt · Freiburg im Breisgau · Gelsenkirchen · Halle an der Saale · Karlsruhe · Kiel · Krefeld · Lübeck · Magdeburg · Mannheim · Münster · Mönchengladbach · Oberhausen · Rostock · Wiesbaden · Wuppertal

100,000+ Bergisch Gladbach · Bottrop · Bremerhaven · Cottbus · Darmstadt · Erlangen · Fürth · Göttingen · Hagen · Hamm · Heidelberg · Heilbronn · Herne · Hildesheim · Ingolstadt · Jena · Kassel · Koblenz · Leverkusen · Ludwigshafen · Mainz · Moers · Mülheim an der Ruhr · Neuss · Offenbach am Main · Oldenburg · Osnabrück · Paderborn · Pforzheim · Potsdam · Recklinghausen · Regensburg · Remscheid · Reutlingen · Saarbrücken · Salzgitter · Siegen · Solingen · Trier · Ulm · Wolfsburg · Würzburg

Members of the Hanseatic League by Quarter Chief cities are highlighted; Free Imperial Cities of the Holy Roman Empire are shown in italics.Wendish Quarter Anklam · Demmin · Greifswald · Hamburg · Kolberg (Kołobrzeg) · Lüneburg · Rostock · Rügenwalde (Darłowo) · Stettin (Szczecin) · Stolp (Słupsk) · Stockholm · Stralsund · Visby · Wismar

Saxon Quarter Baltic Quarter Westphalian

QuarterCologne*

Dortmund*Principal Kontore Subsidiary Kontore Other cities Categories:- Cities in North Rhine-Westphalia

- Populated places established in 38 BC

- Cologne

- Populated places on the Rhine

- Catholic pilgrimage sites

- Holy cities

- Members of the Hanseatic League

- Roman legions' camps in Germany

- Roman colonies

- Roman towns and cities in Germany

- Imperial free cities

- Turkish communities in Germany

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.