- New England English

-

New England English refers to the dialects of English spoken in the New England area. These include the Eastern New England dialect (ENE), the Western New England dialect (WNE), and some Subdialects within these two regions. While many people may think the New England dialects are disappearing or becoming less prevalent, recent research by William Labov suggests that these dialects are growing more distinct and diverse from those elsewhere in the United States.[citation needed]

Contents

Features

Eastern New England speech is historically non-rhotic, while Western New England is historically rhotic. Eastern New England possesses the so-called cot–caught merger; the Providence dialect does not possess the merger; and Western New England exhibits a continuum from full merger in northern Vermont to full distinction in western Connecticut. The Western New England accent is closely related to the Inland North accent which prevails further west.[1]

Regional variances

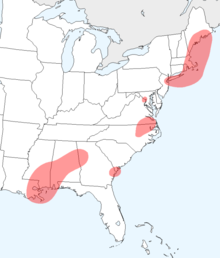

The red areas are those where non-rhotic pronunciation is found among some whites in the United States. AAVE-influenced non-rhotic pronunciations may be found among African-Americans throughout the country. Map based on Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006:48)

The red areas are those where non-rhotic pronunciation is found among some whites in the United States. AAVE-influenced non-rhotic pronunciations may be found among African-Americans throughout the country. Map based on Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006:48)

Within New England English exists a number of dialects.

Eastern New England

Further information: Boston accentEastern New England was originally marked by non-rhoticity in car, card, fear, etc. Though this feature is receding, it is still strong in the area ranging from Bangor, Maine to Providence.

There are several systems of pronouncing "short-a" (the /a/ in pack or bad) attested in the region, including the "nasal" system, remnants of the "broad-a" system, and "Northern breaking".[2]

The Eastern New England dialect region includes much of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, and areas of south-western Nova Scotia, and is frequently said to include Rhode Island and eastern Connecticut.[3][4] Characteristic phonological features include non-rhoticity and a distinctive set of low vowels.

The phrase park the car in Harvard Yard is commonly used to caricature the lack of rhoticity in eastern New England, which contrasts with the generally rhotic accents common elsewhere in North America.[5]

Eastern New England maintains a distinction between the vowel [a] as in father or calm versus [ɒ] as in dog or hot, a pair that is merged in virtually all other North American accents.[4] In contrast, the vowels of caught and cot are pronounced identically, as is the case in most of Canada and the western United States, but not in the southern United States, New York city, Philadelphia, or much of the US Great Lakes region.[6] These vowels are not merged, however, in southeastern New England.

There is evidence that New Hampshire has been shifting over time away from other Eastern New England dialects. Younger speakers have begun to merge the vowels, mentioned above, in father ([a]) and dog ([ɒ]).[7] New Hampshirites have also come to pronounce /r/ with greater frequency than speakers in Massachusetts,[8] and have moved towards a system of "short-a" pronunciation that is distinct from Boston speakers.[2]

Southeastern New England

Southeastern New England includes Rhode Island and areas nearby it in neighboring states such as eastern Connecticut.

As mentioned before, this dialect is traditionally non-rhotic.

A feature that the Southeastern New England accent shares with New York City and much of the Eastern Seaboard is resistance to the cot–caught merger. This also distinguishes the region from Northeastern New England.

Western New England

Western New England is r-pronouncing.

A study of WNE found raising of /æ/ in all environments and tensing (as well as raising) before nasals (Boberg 2001: 17-19).[9] A small sample of telephone survey data showed this to be the case across WNE with the exception of the very northern city of Burlington, Vermont.[10] Words like bad and stack are pronounced with [eə], and words like stand and can are pronounced [ɛə].

Labov (1991: 12) suggests that unified raising of TRAP/BATH/DANCE is a pivot point for the NCVS (the Northern Cities Vowel Shift).[11] Boberg (2001: 11) further argues that the NCVS may thus have had its beginnings in northwestern NE.[9] The existence of this raising pattern is surprising if one accepts the lack of BATH-raising in the LANE data (Kurath 1939-43), especially given that Labov, Ash and Boberg does not show this to be an incipient vigorous change: older speakers show more raising than younger speakers in Hartford, CT, Springfield, MA, and Rutland, VT (Boberg 2001: 19).[9][12]

Recent data from Labov, Ash and Boberg has all western Connecticut speakers keeping cot and caught distinct, resembling the Inland North pattern. However, seven of the eight Vermont speakers have completely merged the two vowels.

As was mentioned earlier, the northern half of this region shows the cot–caught merger, along with consistent fronting of /ɑː/ before /r/.

Southwestern New England shows the basic tendency of the Northern Cities Shift to back /ɛ/ and front /ɑː/.

Some speakers of the Western New England dialect may replace "t" with a glottal stop and replace "-ing" with "in'". This would mean that those who do such would pronounce (for example) "sitting" as "sih-in'", New Britain as "New Bri-in", and so on. T-glotallising is found in other parts of the country as well, in varying amounts. Even the "t" in "Vermont" is often replaced with a glottal stop by native Vermonters.[citation needed]

Some local dialects in working class areas of southwestern Connecticut (especially Greater New Haven and Greater Bridgeport) are strongly influenced by the neighboring New York dialect.

See also

- New England

- Regional accents of English speakers

- Boston English

- Vermont English

- North American English regional phonology #Northeastern dialects

- Regional vocabularies of American English

External links

References

- ^ Nagy, Naomi; Roberts, Julie (2004). "New England phonology". In Edgar Schneider, Kate Burridge, Bernd Kortmann, Rajend Mesthrie, and Clive Upton. A handbook of varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 270–281.

- ^ a b Wood, Jim (2011). "Short-a in Northern New England". Journal of English Linguistics 39 (2): 135–165. doi:10.1177/0075424210366961.

- ^ Schneider, Edgar; Bernd Kortmann (2005). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multi-Media Reference Tool. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 270. ISBN 978-3110175325.

- ^ a b Kurath, Hans; Raven Ioor McDavid (1961). The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States: Based upon the Collections of the Linguistic Atlas of the Eastern United States. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0817301291.

- ^ Wolfram, Walt; Natalie Schilling-Estes (1998). American English: Dialects and Variation. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631204873.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Jim (2006). "Beantown Babble (Boston, MA)". In W. Wolfram and B. Ward. American Voices: How Dialects Differ from Coast to Coast. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1405121092.

- ^ Nagy, Naomi (2001). ""Live Free or Die" as a linguistic principle". American Speech 76 (1): 30–41. doi:10.1215/00031283-76-1-30.

- ^ Nagy, Naomi; Irwin, Patricia (2010). "Boston (r): Neighbo(r)s nea(r) and fa(r)". Language Variation and Change 22 (2): 241–278. doi:10.1017/S0954394510000062.

- ^ a b c Boberg, Charles (2001). "The Phonological Status of Western New England". American Speech 76 (1): 3–29. doi:10.1215/00031283-76-1-3.

- ^ Labov, William; Sharry Ash, Charles Boberg (2006). The atlas of North American English. Mouton. ISBN 3110167468.

- ^ Labov, William (1991). "The three dialects of English". In Penelope Eckert. New ways of analyzing sound change. Academic Press.

- ^ Kurath, Hans (editor) (1939-43). Linguistic Atlas of New England (3 vols). Brown University.

Categories:- New England

- American English

- American slang

- Connecticut culture

- Maine culture

- Massachusetts culture

- New Hampshire culture

- Rhode Island culture

- Vermont culture

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.