- Capital punishment in Texas

-

The Huntsville Unit in Huntsville, Texas is the location of the execution chamber of the state of Texas

The Huntsville Unit in Huntsville, Texas is the location of the execution chamber of the state of Texas

Capital punishment has been used in the U.S. state of Texas and its predecessor entities since 1819. As of 27 October 2011, 1,227 individuals (all but six of whom have been male) have been executed.[1] As of 2010 the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) houses death row prisoners after they are transported from their counties of conviction, and the TDCJ administers the death penalty on a condemned person's court-scheduled date of execution.[2]

Texas has used a variety of execution methods – hanging (until 1924), shooting by firing squad (used only four times during the Civil War period), electrocution (1924–1964) and lethal injection (1982 to present). Most executions were for murder, but other crimes such as piracy, cattle rustling, treason, desertion and rape have been subject to death sentences. Six sets of brothers have been executed, the most recent being Jessie (9/16/1994) and Jose (11/18/1999) Gutierrez.

Under current state law, the crimes of capital murder and capital sabotage (see Texas Government Code §557.012) or a second conviction for the aggravated sexual assault of someone under 14 is eligible for the death penalty (though the recent Supreme Court case Kennedy v. Louisiana removed the death penalty option for rapists). In order for a murder to be a "capital murder," it must meet one of the circumstances described below under the Capital Offenses section.

Since the death penalty was re-instituted in the United States in the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia decision, Texas has executed (all via lethal injection) more inmates than any other state (beginning in 1982 with the execution of Charles Brooks Jr.), notwithstanding that two states (California and Florida) have a larger death row population than Texas.

Male death row inmates are held at the Allan B. Polunsky Unit and female death row inmates are held at the Mountain View Unit, while all executions occur at Huntsville Unit.

History

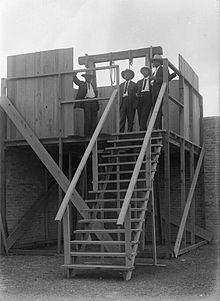

Gallows in Brownsville, Texas prior to the hanging of two men in 1916

Gallows in Brownsville, Texas prior to the hanging of two men in 1916

Prior to statehood in 1845, eight executions were carried out; all were by hanging. Upon statehood, hanging would be the method used for almost all executions until 1924. Hangings were administered by the county where the trial took place. The last hanging in the state was that of Nathan Lee, a man convicted of murder and executed in McKinney, Texas on August 31, 1923. The only other method used at the time was execution by firing squad, which was used for three Confederate deserters during the American Civil War as well as a man convicted of attempted rape in 1863.[citation needed]

Ellis Unit, which at one time housed the State of Texas male death row

Ellis Unit, which at one time housed the State of Texas male death row

Texas changed its execution laws in 1923, requiring the executions be carried out on the electric chair and that they take place at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville (also known as Huntsville Unit). From 1928 until 1965, this was also home to the state's male death row. The first executions on the electric chair were on February 8, 1924 when Charles Reynolds, Ewell Morris, George Washington, Mack Matthews, A black man, and Melvin Johnson had their death sentences carried out. The five executions were the most carried out on a single day in the state. The state would conduct multiple executions on a single day on several other occasions, the last being on September 5, 1951. Since then, the state has not executed more than one person on a single day, though there is no law prohibiting such. A total of 361 people were electrocuted by the state, with the last being Joseph Johnson on July 30, 1964.[citation needed]

The United States Supreme Court decision in Furman v. Georgia (408 U.S. 238 (1972)), which declared Georgia's "unitary trial" procedure (in which the jury was asked to return a verdict of guilt or innocence and, simultaneously, determine whether the defendant would be punished by death or life imprisonment) to be unconstitutional on the grounds that it was a cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution, essentially negated all death penalty sentences nationwide. At the time of the decision 52 inmates (45 on death row and seven in county jails awaiting transfer to TDCJ) had been given the death penalty; all were commuted to life in prison.[3]

The Furman decision led to a 1973 revision of the laws, primarily by introducing the bifurcated trial process (where the guilt-innocence and punishment phases are separate) and narrowly limiting the legal definition of capital murder (and, thus, those offenses for which the death penalty could be imposed). The first person sentenced to death under this new statute was John Devries on February 15, 1974; Devries hanged himself in his cell on July 1, 1974 (using bedsheets from his bunk) before he could be executed.[3]

The Supreme Court decision in Gregg v. Georgia in 1976 once again allowed for the death penalty to be imposed (a case from Texas was also involved in the Gregg decision and was upheld by the Court). However, the first execution in Texas after this decision would not take place until December 7, 1982 with that of Charles Brooks, Jr.. Brooks was also the first person to be judicially executed by lethal injection in the world, and the first African American to be executed in the United States since 1967.

In the post-Gregg era Texas has executed over four times more inmates than Virginia (the state with the second-highest number of executions in the post-Gregg era) and nearly 34 times more inmates than California (the state with the largest death row population). The TDCJ website maintains a list of inmates with scheduled execution dates, which is generally updated within 1–2 days after an execution takes place or a stay of execution is granted. TDCJ List of Scheduled Executions

Capital offenses

With one exception, the only crime for which the death penalty can be assessed is "capital murder".

Unlike the Model Penal Code (which does not specifically define the crime of capital murder), the Texas Penal Code specifically defines capital murder (and, thus, the possibility of the death penalty as a punishment) as murder which involves one or more of the elements listed below:[4]

- Murder of an on-duty public safety officer or firefighter (the defendant must have known that the victim was such)

- Intentional murder in the course of committing or attempting to commit a felony offense (such as burglary, robbery, aggravated sexual assault, arson, obstruction or retaliation, or terroristic threat)

- Murder for remuneration or for promise of remuneration (both the person who does the actual murder and the person who hired them can be charged with capital murder)

- Murder while escaping or attempting to escape a penal institution

- Murder while incarcerated with one of the following three qualifiers:

- While incarcerated for capital murder, the victim is an employee of the institution or the murder must be done "with the intent to establish, maintain, or participate in a combination or in the profits of a combination",

- While incarcerated for either capital murder or murder, or

- While serving either a life sentence or a 99-year sentence under specified Penal Code sections not involving capital murder or murder.

- Multiple murders (defined as two or more murders during the same "criminal act", which can involve a series of events not taking place at the same time)

- Murder of an individual under ten years of age

- Murder of a person in retaliation for, or on account of, the service or status of the other person as a judge or justice of any court

The Texas Penal Code also allows for the death penalty to be assessed for "aggravated sexual assault of child committed by someone previously convicted of aggravated sexual assault of child".[5] The statute remains part of the Penal Code; however, the Supreme Court of the United States's decision in Kennedy v. Louisiana which outlawed the death penalty for any crime not involving murder nullifies its effect.

The Texas Penal Code also allows a person can be convicted of any felony, including capital murder, "as a party" to the offense. "As a party" means that the person did not personally commit the elements of the crime, but is otherwise responsible for the conduct of the actual perpetrator as defined by law; which includes:

- soliciting for the act,

- encouraging its commission,

- aiding the commission of the offense,

- participating in a conspiracy to commit any felony where one of the conspirators commits the crime of capital murder

The felony involved does not have to be capital murder; if a person is proven to be a party to a felony offense and a murder is committed, the person can be charged with and convicted of capital murder, and thus eligible for the death penalty.

As in any other state, people who are under 18 at the time of commission of the capital crime [6] or mentally retarded[7] are precluded from being executed by the Constitution of the United States.

Legal procedure

Trial phase

A capital trial in Texas is a bifurcated trial, consisting of the "guilt-innocence phase" (where the jury must determine if guilt has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt) followed by the "punishment phase" (in which the jury determines whether the person will be sentenced to death or life in prison).

Guilt-innocence phase

The guilt-innocence phase in a capital case in Texas proceeds identically to a non-capital case with the exception of voir dire (jury selection). In a capital case, voir dire is conducted on each potential juror individually rather than as a group, and voir dire must result in a death-qualified jury.

Punishment phase

A punishment phase will not take place if the death penalty will not be imposed. Reasons for such include:

- The person was under 18 at the time of the crime and, thus, cannot be sentenced to death (Roper v. Simmons)

- Both the prosecution and defense agree that the person was mentally retarded at the time of the crime and, thus, cannot be sentenced to death (Atkins v. Virginia)

- The prosecution has chosen not to seek the death penalty. This can be for various reasons, such as the prosecution believing that they could not show the defendant worthy of death, or the family has asked that the death penalty not be imposed (in Texas, the district attorney for the county is in charge of prosecutorial staff; as the district attorney is an elected position, not deferring to a family's wishes could make re-election difficult).

If no punishment phase is held, the sentence is life imprisonment, with the actual sentence as follows:

- For crimes committed on or after September 1, 2005, the sentence is life imprisonment without the possibility of parole

- For crimes committed on or after September 1, 1991 but prior to September 1, 2005, the sentence is life imprisonment with the possibility of parole, but the offender must serve 40 calendar years before it can be considered.

- For crimes committed prior to September 1, 1991, the sentence is life imprisonment with the possibility of parole, with no minimum calendar time required to be served.

As a result of the special issues in death penalty cases, there are different rules of evidence that apply in capital cases in the punishment phase than for a non-capital case. In a non-capital case, the State may introduce evidence of prior bad acts that did not result in a conviction only if "shown beyond a reasonable doubt by evidence to have been committed by the defendant or for which he could be held criminally responsible." There exists no such limitation in capital cases, and the State may introduce evidence "as to any matter that the court deems relevant to sentence" without any burden of proof. As a result, the State may present evidence in the punishment phase relating to a case for which the capital defendant has in the past already been tried and acquitted on, and this has happened in Texas.

Since the re-introduction of the death penalty, Texas has always required the jury to decide whether to impose the death penalty in a specific case. However, Texas did not adopt the "aggravating factor" approach outlined in the Model Penal Code. Instead, once each side has pleaded its case, the jury must answer two questions (three, if the person was convicted as a party) to determine whether a person will or will not be sentenced to death:

- The first question is whether there exists a probability the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a "continuing threat to society". "Society" in this instance includes both inside and outside of prison; thus, a defendant who would constitute a threat to people inside of prison, such as correctional officers or other inmates, is eligible for the death penalty.

- The second question is whether, taking into consideration the circumstances of the offense, the defendant's character and background, and the personal moral culpability of the defendant, there exists sufficient mitigating circumstances to warrant a sentence of life imprisonment rather than a death sentence.

- If the person was convicted as a party, the third question asked is whether the defendant actually caused the death of the deceased, or did not actually cause the death of the deceased but intended to kill the deceased, or "anticipated" that a human life would be taken.

In order for a death sentence to be imposed, the jury must answer the first question 'Yes' and the second question 'No' (and, if convicted as a party, the third question 'Yes'). Otherwise the sentence is life in prison.

Direct appeal of conviction

The imposition of a death sentence in Texas results in an automatic direct appeal to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the state's highest criminal tribunal (the intermediate Texas Court of Appeals is bypassed), which examines the record for trial error.

Habeas corpus appeals

Beyond the direct appeal stage, any appeals not involving habeas corpus to the Federal level are not automatic and must be requested via writ of certiorari. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has jurisdiction over Texas.

In Texas, capital defendants have a state statutory (not constitutional) right to representation by counsel during their initial state habeas corpus proceedings. Habeas proceedings, unlike direct appeals, consider matters extraneous to the trial record in order to determine the constitutionality of the proceedings and hence the validity of the conviction and sentence.

The habeas attorney is appointed at the same time as the direct appeal attorney, and the habeas application is due within 180 days. Although Article 11.071 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure guarantees the defendant ‘competent counsel’ in his state habeas corpus proceedings, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has held that this refers merely to the initial qualifications of the attorney, not to the end product of his representation.

Following a hearing, if any, the defendant's counsel and the State both submit proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law, the trial court is to make its own written findings of fact and conclusions of law regarding the application, and the case is then transferred to the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas, which can adopt or reject the findings and conclusions of the trial court, and will then render an order either granting or denying a new trial.

Subsequent or successive writ applications

A subsequent petition for a writ of habeas corpus is any that is filed after the first. If that writ contains claims that were also raised in a previous writ then it is known as a ‘successive petition’, it if has claims in that could have been raised previously but were not it is called an ‘abusive petition/writ’, though bear in mind that these terms may used fairly interchangeably.

Section 11.071 §5 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure deals with subsequent habeas corpus petitions. The general rule (as in most others that regularly use the death penalty) is that the defendant must raise all the claims it wishes in the first habeas corpus writ. After this any subsequent habeas writ, whether it contains new evidence or not, will be rejected on procedural grounds without the courts considering the merits. However, a subsequent writ may be granted if any one of the four following exceptions are met:

- i) the petition raises a claim based on facts that were unavailable at the time of the original petition

- Generally a petition raising new factual evidence under the first exception will only be accepted if it is the subject of a Brady claim, meaning the prosecution has suppressed the evidence and therefore the defendant could not have had access to it at the time of their first petition.

- ii) the claim is based on case-law developed subsequent to the original petition

- This exception is currently the subject of ongoing litigation, as a defendant is required to argue opposite positions in state and federal court; a federal court may only grant habeas relief if the state court has misapplied ‘clearly established’ federal law, while a Texas court may only grant relief if the defendant wants to take advantage of a ‘new’ rule of law.

- iii) if the claim raises evidence showing that the defendant would not have been convicted but for a violation of the US Constitution

- This exception concerns claims of actual innocence of the crime for which the defendant has been convicted. These claims have to show that, by a preponderance of the evidence, the defendant would not have been convicted but for a violation of the US Constitution. Although preponderance of the evidence is not an especially high burden of proof, the defendant is also required to show a violation of the US Constitution, which can be much more difficult to prove. A claim in a subsequent petition that merely claims a defendant is innocent without a Constitutional violation will not be considered.

- iv) the claim raises evidence showing that the jury in the defendant’s trial would not have answered the two (or three) death penalty questions (see the Punishment Phase section above) in the State’s favor but for a violation of the US Constitution

- This exception applies to situations where some Constitutional defect in the trial or appeal means that no rational juror could have voted for the defendant to receive the death penalty. Note though that, as with exception iii), this kind of claim is dependent on there being some other problem with the defendant’s trial, but under this exception the burden of proof standard is clear and convincing evidence, a higher standard than under exception iii). This exception is important for subsequent or successive petitions making an Atkins claim of mental retardation, as a successful petition will automatically render a defendant ineligible for the death penalty. Unlike exception iii) the court will consider successive petitions raising such a claim without an accompanying Constitutional violation.

The first two exceptions allow subsequent petitions regarding new evidence, but only if it was unavailable at the time of the previous petition; this obviously excludes successive petitions containing no new claims from being considered under either of these two exceptions. The second two exceptions have no such limitations and potentially allow a defendant to file a successive petition and re-litigate claims that have already been rejected; however the standard of evidence that the defendant must show is extremely high.[citation needed]

Board of Pardons and Paroles

In addition, a defendant may also appeal to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles (a division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice) for commutation of the sentence.

The Board, after hearing testimony, decides whether or not to recommend commutation to the Governor of Texas. The Governor can accept or reject a positive recommendation of commutation, but has no power to override a negative recommendation (the law was changed in 1936 due to concerns that pardons were being sold for cash under the administrations of former Governor James E. Ferguson and later his wife and Texas' first female Governor Miriam A. Ferguson).[8] The only unilateral action which the Governor can take is to grant a one-time, 30-day reprieve to the defendant.[9][10]

It should be noted that the Board members are gubernatorial appointees (though their terms overlap gubernatorial elections) and, thus, will most likely share the same political viewpoints as the Governor who appointed them.

Processing, transportation, and confinement

Male death row inmates are housed at the Polunsky Unit in West Livingston;[3][11] female death row inmates are housed at the Mountain View Unit in Gatesville. All death row inmates at both units are physically segregated from the general population, recreate individually, and have individual 60 square feet (5.6 m2) cells. They receive special death row ID numbers instead of regular Texas Department of Criminal Justice numbers.[3]

Death row prisoners, along with prisoners in administrative segregation, are seated individually on prison transport vehicles. The TDCJ makes death row prisoners wear various restrains, including belly chains and leg irons, while being transported.[12] Death row offenders and offenders with life imprisonment without parole enter the TDCJ system through two points; men enter through the Byrd Unit in Huntsville, and women enter through the Reception Center in Christina Crain Unit, Gatesville. From there, death row inmates go to their designated death row facilities.[13]

Establishing the date of execution

The judge presiding over a capital case sets the execution date once it appears that all the offender's appeals have been exhausted.[14] The initial date of execution cannot be prior to the 91st day after the day the order is entered and (if the original order is withdrawn) subsequent execution dates cannot be less than the 31st day after the order is entered, provided that no habeas corpus motion has been filed under Article 11.071; otherwise, the date cannot be set prior to the court either denying relief, or issuing its mandate.[15] In the event an offender manages to escape confinement, and not be re-arrested until after the set execution date, the revised date of execution shall be not less than 30 days from the date the order is issued.[16][17]

Execution procedure

The law does not prohibit multiple executions in a single day; however, Texas has not executed multiple offenders on a single day since September 5, 1951, when three offenders were executed on that day.[18]

The law only specifies that "[t]he execution shall take place at a location designated by the Texas Department of Corrections in a room arranged for that purpose."[19] However, since 1923, all executions have been carried out at the Huntsville Unit, the former location of death row.

On the afternoon of a prisoner's scheduled execution,[20] he or she is transported directly from his or her death row unit to the Huntsville Unit.[21] Men leave the Polunsky Unit in a three-vehicle convoy bound for the Huntsville Unit; [20] women leave from the Mountain View Unit. The only individuals who are informed of the transportation arrangements are the wardens of the affected units. The TDCJ does not make an announcement regarding what routes are used, what dates the transportation will occur on, or what methods of transportation will be used.[21]

Upon arrival at the Huntsville Unit, the condemned is led through a back gate, submits to a cavity search, then is placed in a holding cell.

Before 2011, the condemned was given an opportunity to have a last meal based on what the unit's cafeteria could prepare from its stock. Robert Perkinson, author of Texas Tough: The Rise of America's Prison Empire, said in 2010 that most condemned prisoners order "standard American fare in heaping portions, the sorts of meals that recall a childhood Sunday."[20] Many female prisoners under the death sentence did not take a last meal.[22] However, Lawrence Russel Brewer, a white supremacist gang member convicted for the high-profile hate crime dragging death of James Byrd, Jr., ordered a large last meal and did not eat it before his execution. In response, John Whitmire, a member of the Texas legislature, asked the TDCJ to stop special meals. Whitmire stated to the press that Brewer's victim, Mr. Byrd, "didn't get to choose his last meal." The TDCJ complied. Brian Price, a former prison chef, offered to personally cook and pay for any subsequent special last meal since the TDCJ is not paying for them anymore.[23] However, Whitmire warned in a letter that he would seek formal state legislation when lawmakers next convened if the "last meal" tradition wasn't stopped immediately.[24] Afterwards, the TDCJ stopped serving special last meals, and will only allow execution chamber prisoners to have the same kind of meal served to regular prisoners.[25] Many prisoners requested cigarettes (which were denied as TDCJ has banned smoking in its facilities).

Under Texas law, executions are carried out at or after 6 p.m. Huntsville (Central) time "by intravenous injection of a substance or substances in a lethal quantity sufficient to cause death and until such convict is dead".[26] The law does not specify the substance(s) to be used; according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice the chemicals used for the lethal injection are the commonly-used three-drug combination of (in order) sodium thiopental (a lethal dose which sedates the offender), pancuronium bromide (a muscle relaxant which collapses the diaphragm and lungs), and potassium chloride (which stops the heartbeat). The offender is usually pronounced dead approximately seven minutes after start of the injection process; the cost for the three substances is $86.08 per offender.[3] As a result of drug shortages, sodium thiopental was replaced by pentobarbital in 2011.[27] Further shortages of this drug have pushed the cost of the drugs to approximately $1300 per offender.[28]

The only persons legally allowed to be present at the execution are:[29]

- the executioner "and such persons as may be necessary to assist him in conducting the execution"

- the Board of Directors of the Department of Corrections

- two physicians including the prison physician

- the spiritual advisor of the condemned

- the chaplains of the Department of Corrections

- the county judge and sheriff of the county in which the crime was committed

- no more than five relatives or friends of the condemned person

However, no convict is permitted to be a witness to an execution.

In response to victims rights groups, TDCJ adopted a board rule in January 1996 allowing five victim witnesses (six for multiple victims). Initially the witnesses were limited to immediate family and individuals with a close relationship to the victim, but the board rule was modified in 1998 to allow close friends of surviving witnesses, and further modified in May 2008 to allow the victim witnesses to be accompanied by a spiritual advisor who is a bona fide pastor or comparable official of the victim's religion.[30]

In addition, five members of the media are also allowed to witness the execution, divided equally as possible between the rooms containing the offender's and victim witnesses.[31] Under current TDCJ guidelines, a representative of both the Associated Press and the Huntsville Item (the local newspaper) are guaranteed slots to witness an execution (Michael Graczyk from the AP's Houston office is a frequent attender, having attended over 300 executions).[32] Other media members must submit their requests at least three days prior to the execution date; priority will be given to media members representing the area in which the capital crime took place. College and university media are not permitted to be witnesses.[33]

Upon the offender's death the body shall be immediately embalmed, and shall be disposed of as follows:[34]

- A relative or bona fide friend of the offender may demand or request the body within 48 hours after death, upon payment of a fee not to exceed US$25 for the mortician's services in embalming the deceased; once TDCJ receives the receipt the body shall be released to the requestor or his/her authorized agent.

- If no relative or bona fide friend requests the body, the Anatomical Board of the State of Texas may request the body, but must also pay the US$25 fee for embalming services and TDCJ must receive the receipt prior to delivery.

- If no relative, bona fide friend, or the Anatomical Board requests the body, TDCJ shall cause the body to be "decently buried" with the embalming fee to be paid by the county in which the indictment resulting in the conviction occurred.

Captain Joe Byrd Cemetery in Huntsville, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison cemetery for deceased prisoners, including executed prisoners, who are not reclaimed by their families

Captain Joe Byrd Cemetery in Huntsville, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison cemetery for deceased prisoners, including executed prisoners, who are not reclaimed by their families

Reasons for the high number of executions

There are a variety of proposed legal and cultural explanations as to why Texas has more executions than any other state.

- One major reason is due to population size – Texas has the second-largest population of any state, trailing only California. However, while California's death row is larger than Texas'; since 1976 (when Gregg v. Georgia once again permitted the imposition of the death penalty) Texas has executed over 450 inmates, while California has executed only 13 and none since January 17, 2006.[35]

- Another reason is due to Texas' political climate, which generally leans conservative and in favor of capital punishment. Since 1994, every statewide office has been held by the Republican Party, including the nine judges of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (by law, the judges of this court – which on direct appeal reviews all death penalty cases – are elected, not appointed as in other states).[36] A 2002 Houston Chronicle poll of Texans found that when asked "Do you support the death penalty?" 69.1% responded that they did, 21.9% did not support and 9.1% were not sure or gave no answer.[citation needed]

- Another reason is due to the federal appellate structure – federal appeals from Texas are made to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. Michael Sharlot, dean of the University of Texas at Austin Law School, found the Fifth Circuit to be a "much more conservative circuit" than the neighboring Ninth. According to him, the Fifth is "more deferential to the popular will" that is strongly pro-death penalty and creates few legal obstacles to execution within its jurisdiction.[37][38]

Texas may have a much lower rate of death sentencing than other states, according to a study by Cornell University faculty members. The study showed that states with more objective laws defining a death penalty offense (such as Texas; as shown in the Capital Offenses section above Texas has defined specific, objective circumstances which constitute a capital murder offense) sentenced defendants to death less (about 1.9 percent in 1977-99) than states whose laws were more subjective in defining a death penalty offense (which assigned it about 2.7 percent during that period).[39]

Alleged execution of innocent persons

See also: Wrongful executionTexas' active use of the death penalty has led death penalty opponents to claim that Texas has executed persons who were, in fact, innocent. One notable case involves Cameron Todd Willingham, who was executed by lethal injection on February 17, 2004 for murdering his three daughters in 1991 by arson, but where a 2009 article in The New Yorker, and subsequent findings, have cast doubt on the evidence used in his conviction.

In 2009, a report conducted by Dr. Craig Beyler, hired by the Texas Forensic Science Commission to review the case, found that "a finding of arson could not be sustained". Beyler said that key testimony from a fire marshal at Willingham's trial was "hardly consistent with a scientific mind-set and is more characteristic of mystics or psychics”.[40]

Governor Rick Perry has expressed skepticism of Beyler's findings. He stated that court records showed evidence of Willingham’s guilt in charges that he intentionally killed his daughters in the fire. Perry is quoted in the report as stating of Willingham, "I’m familiar with the latter-day supposed experts on the arson side of it," and Perry said that court records provide "clear and compelling, overwhelming evidence that he was in fact the murderer of his children."[41]

On July 23, 2010, the Texas Forensic Science Commission released a report saying that the conviction was based on "flawed science" and that there is no indication that the arson authorities were negligent or committed willful misconduct.[42]

Execution of Mexican nationals

Further information: José Medellín and Humberto Leal GarciaTwo Mexican nationals have been recently executed in Texas – José Medellín in 2008, and Humberto Leal Garcia in 2011. At the time of their arrests in the early 1990s, neither had been informed of their rights as Mexican nationals to have the Mexican consulate informed of the charges and provide legal assistance. A 2004 ruling by the International Court of Justice concluded that the U.S. had violated the rights of 51 Mexican nationals, including Medellin and Garcia, under the terms of a treaty the U.S. had signed.[43] In response to the ruling, the Bush administration issued an instruction that states comply,[44] but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that he had exceeded his authority. The Supreme Court also ruled in Medellin v. Texas that the treaty was not binding on states until Congress enacted statutes to implement it, and in Leal Garcia v. Texas declined to place a stay on the executions in order to allow Congress additional time to enact such a statute. A 2008 ruling by the International Court of Justice asked the United States to place a stay on the executions, but Texas officials stated that they were not bound by international law.[45]

Garcia supporters complained about the use of bite mark analysis and luminol in determining his guilt.[46] However, Garcia accepted responsibility for the crimes and apologized before his execution.[47]

Regarding the Garcia execution, Texas Governor Rick Perry stated that "If you commit the most heinous of crimes in Texas, you can expect to face the ultimate penalty under our laws."[48]

Opposition

See also: Capital punishment debateThe Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, a 501c3 grassroots membership organization was founded in 1998. TCADP has members across the state of Texas working to educate their local communities on the problems of the Texas death penalty. TCADP hosts multiple education and training opportunities each year around the state including releasing an annual report on December 7 and a day-long annual conference which includes workshops, panel discussions, networking and awards. The conference is held in Austin during legislative years and in other Texas Cities in non-legislative years (2012: San Antonio). TCADP opened a state office in Austin in 2004 with a paid program coordinator and hired an executive director in 2008. TCADP is affiliated with the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty.

Protesters gather at the front gate of the Texas Governor's Mansion during the "6th Annual March to Stop Executions

Protesters gather at the front gate of the Texas Governor's Mansion during the "6th Annual March to Stop Executions

The March to Abolish the Death Penalty is the current name of an event organized each October since 2000 by several Texas anti-death penalty organizations, including Texas Moratorium Network, the Austin chapter of the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, the Texas Death Penalty Abolition Movement and Texas Students Against the Death Penalty.[49] Anti-Death Penalty Alternative Spring Break is an annual event started by Texas Moratorium Network in 2004 and now co-organized by Texas Students Against the Death Penalty. It serves as a training ground for students who oppose the death penalty.[50]

The Death Row Inner-Communalist Vanguard Engagement (D.R.I.V.E.) consists of several male death row inmates from the Polunsky Unit. Through a variety of non-violent strategies, they have begun launching protests against the perceived bad conditions at Polunsky, in particular, and capital punishment, in general. They actively seek to consistently voice complaints to the administration, to organize grievance filing to address problems. They occupy day rooms, non-violently refuse to evacuate their cells or initiate sit-ins in visiting rooms, hallways, pod runs and recreation yards when there is the perception of an act of abuse of authority by guards (verbal abuse; physical abuse; meals/recreations or showers being wrongly denied; unsanitary day rooms and showers being allowed to persist; medical being denied; paper work being denied; refusing to contact higher rank to address the problems and complaints) and when alleged retaliation (thefts, denials, destruction of property; food restrictions; wrongful denials of visits; abuse of inmates) is carried out in response to their grievances.

See also

- List of individuals executed in Texas

- Michael Graczyk, Houston-based reporter who has witnessed over 300 executions in Texas

- The Rope, the Chair, and the Needle: Capital Punishment in Texas, 1923-1990

- Crime in Texas

References

- ^ Summing Texas Executions 1819–1964 and Executed offenders (1982-present) from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice

- ^ "Death row." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on September 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Death Row Facts." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on May 6, 2010.

- ^ "Texas Penal Code, Section 19.03, "Capital Murder"". http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/Docs/PE/pdf/PE.19.pdf. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ "Texas Penal Code, Section 12.42, "Penalties for Repeat and Habitual Felony Offenders", subsection (c)(3)". http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/Docs/PE/pdf/PE.12.pdf. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- ^ Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005)

- ^ Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002)

- ^ Texas State Libraries and Archives Commission: "Pardons and Paroles" retrieved October 20, 2011]

- ^ Texas Administrative Code Title 37 PUBLIC SAFETY AND CORRECTIONS, Part 5 TEXAS BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLES, Chapter 143 EXECUTIVE CLEMENCY, Subchapter E COMMUTATION OF SENTENCE, Rule 143.57 Commutation of Death Sentence to Lesser Penalty retrieved August 20, 2011

- ^ The Texas Constitution: Sec. 11. BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLES; PAROLE LAWS; REPRIEVES, COMMUTATIONS, AND PARDONS; REMISSION OF FINES AND FORFEITURES, subsection b (Amended Nov. 3, 1936, Nov. 8, 1983, and Nov. 7, 1989.) stating "In all criminal cases, except treason and impeachment, the Governor shall have power, after conviction, on the written signed recommendation and advice of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, or a majority thereof, to grant reprieves and commutations of punishment and pardons; and under such rules as the Legislature may prescribe, and upon the written recommendation and advice of a majority of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, he shall have the power to remit fines and forfeitures. The Governor shall have the power to grant one reprieve in any capital case for a period not to exceed thirty (30) days; and he shall have power to revoke conditional pardons. With the advice and consent of the Legislature, he may grant reprieves, commutations of punishment and pardons in cases of treason." retrieved August 20, 2011

- ^ "West Livingston CDP, Texas." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 9, 2010.

- ^ "More than 500,000 prisoners transported annually Bus Stop: Transportation officers keep offender traffic moving." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. March/April 2005. Retrieved on October 26, 2010.

- ^ "Life without parole offenders face a lifetime of tight supervision." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on July 7, 2010.

- ^ "Scheduled Executions." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on May 9, 2010. "The judge presiding over a capital punishment case sets the date of execution for a death row offender when it appears that appeals in the case have been exhausted."

- ^ Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 43.141, "Scheduling of execution date; Withdrawal; Modification"

- ^ Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 43.21, "Escape after sentence"

- ^ Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 43.22, "Escape from Department of Corrections"

- ^ http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/ESPYstate.pdf

- ^ Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 43.19, "Place of execution"

- ^ a b c Perkinson, Robert. Texas Tough: The Rise of America's Prison Empire. First Edition. Metropolitan Books, 2010. 39. ISBN 978-0-8050-8069-8.

- ^ a b Crawford, Bill. Texas Death Row: Executions in the Modern Era. Penguin Publishing, 2008. viii. Retrieved from Google Books on November 1, 2010. ISBN 0452289300, 9780452289307

- ^ Perkinson, Robert. Texas Tough: The Rise of America's Prison Empire. First Edition. Metropolitan Books, 2010. 40. ISBN 978-0-8050-8069-8.

- ^ Lateef, Mungin. "Former death row chef offers to cook free meals for the condemned." CNN. October 2, 2011. Retrieved on October 2, 2011.

- ^ Associated Press. "Texas death row ends 'last meal' offers after killer's massive tab (+More Weird 'Last Meals')." myWestTexas.com. September 22, 2011. Retrieved on October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Texas drops special last meal for death row inmates." CNN. Thursday September 22, 2011. Retrieved on September 22, 2011.

- ^ Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 43.14, "Execution of Convict"

- ^ MacLaggan, Corrie (16 March 2011). MSNBC. Reuters. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/42113794/ns/us_news-crime_and_courts/t/executions-texas-switches-drug-used-animals/.

- ^ Welsh-Huggins, Andrew (9 July 2011). AP. http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5hE14YzSePrXvm6QuKjUtZjf6Kglw?docId=203afa09b7944f9f81df007c6806f9ca.

- ^ Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 43.20, "Present at Execution"

- ^ http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/victim/victim-viewexec.htm

- ^ http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/victim/victim-viewexec.htm

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (October 21, 2009). "One Reporter’s Lonely Beat, Witnessing Executions". The New York Times (nytimes.com): pp. A1. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/21/business/media/21execute.html. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/divisions/pio/pio_directive_media_relations.html

- ^ Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 43.25, "Body of convict"

- ^ Death Row Inmates by State, Order by State Population

- ^ Welcome to the official site of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals!

- ^ As quoted in Robert Bryce, "Why Texas is Execution Capital," The Christian Science Monitor, December 14, 1998.

- ^ Walpin, Ned (December 5, 2000). "Why is Texas #1 in Executions?". Frontline (pbs.org). http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/execution/readings/texas.html. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ "Cornell study reveals surprising findings on death row, race and the most death penalty-prone states." Cornell University. February 26, 2004. Retrieved on May 9, 2010.

- ^ Full Text of Report on Analysis of Arson Fire Investigation in Todd Willingham Case | Texas Moratorium Network (August 2009)

- ^ Texas Governor Defends Controversial Execution

- ^ Turner, Allan. ""Flawed science" helped lead to Texas man's execution." Houston Chronicle. July 23, 2010. Retrieved on July 23, 2010.

- ^ "Avena and other Mexican Nationals (Mexico v. United States of America)". The Hague Justice Portal. http://www.haguejusticeportal.net/eCache/DEF/6/186.html. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ^ http://www.humbertoleal.org/docs/Bush-memorandum.pdf

- ^ "Court seeks to stay US executions". BBC News. 2008-07-16. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7510073.stm. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ^ "Courthouse News Service". Courthousenews.com. 2011-07-08. http://www.courthousenews.com/2011/07/08/38009.htm. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ^ "Texas executes Mexican after US court rejects appeal". BBC. 2011-07-08. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-14041953. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ^ Graczyk, Michael (2011-07-08). "Criticism of Texas' execution of Mexican Leal doesn't bother Perry". Star-telegram.com. http://www.star-telegram.com/2011/07/08/3209871/criticism-of-texas-execution-of.html. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ^ Protesters march to call for an end to executions

- ^ Alternative Spring Break: Learning how to participate in the legislative process

http://www.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/07/07/texas.mexican.execution/index.html?hpt=hp_t2

External links

- Narratives of family members and friends of people who have died in acts of violence, ex-cons, lawyers, educators and activists from the Texas After Violence Project

- Death Row Information, by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice

- Texas Death Penalty Blog, by The Dallas Morning News

- "Inside the Texas Death Chamber", photo gallery accompanied by audio track, The Associated Press

- Texas execution chamber today Texas in 1982

Capital punishment in the United States In depth Federal Government · Military · Alabama · Arkansas · California · Colorado · Connecticut · Florida · Idaho · Indiana · Louisiana · Maine · Maryland · Massachusetts · Michigan · Mississippi · Nebraska · Nevada · New Hampshire · New Jersey · New Mexico · New York · Ohio · Oklahoma · Oregon · Rhode Island · South Dakota · Texas · Utah · Vermont · Virginia · Washington · West Virginia · Wisconsin · WyomingLists of individuals executed Alabama · Arizona · Arkansas · California · Colorado · Connecticut · Delaware · Florida · Georgia · Idaho · Illinois · Indiana · Kansas · Kentucky · Louisiana · Maryland · Michigan · Mississippi · Missouri · Montana · Nebraska · Nevada · New Hampshire · New Jersey · New Mexico · New York · North Carolina · Ohio · Oklahoma · Oregon · Pennsylvania · South Carolina · South Dakota · Tennessee · Texas · Utah · Virginia · Washington · WyomingOther Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.