- Portland, Oregon

-

Portland — City — City of Portland Portland's skyline from the west, with Mount Hood on the left

Flag

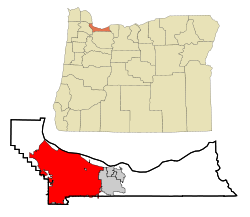

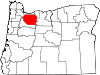

SealNickname(s): "Rose City", "Stumptown", "PDX"[1] See Nicknames of Portland, Oregon for a complete listing. Location of Portland in Multnomah County and the state of Oregon Location in the United States Coordinates: 45°31′12″N 122°40′55″W / 45.52°N 122.68194°WCoordinates: 45°31′12″N 122°40′55″W / 45.52°N 122.68194°W Country USA State Oregon Counties Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas Founded 1845 Incorporated February 8, 1851 Government – Type Commission – Mayor Sam Adams[2] – Commissioners Randy Leonard

Dan Saltzman

Nick Fish

Amanda Fritz– Auditor LaVonne Griffin-Valade Area – City 145.4 sq mi (376.5 km2) – Land 134.3 sq mi (347.9 km2) – Water 11.1 sq mi (28.6 km2) Elevation 50 ft (15.2 m) Population (2010) – City 583,776 – Density 4,288.38/sq mi (1,655.31/km2) – Metro 2,260,000 – Demonym Portlander Time zone PST (UTC-8) – Summer (DST) PDT (UTC-7) ZIP codes 97086-97299 Area code(s) 503 and 971 FIPS code 41-59000[3] GNIS feature ID 1136645[4] Website www.portlandonline.com Portland is a city located in the Pacific Northwest, near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2010 Census, it had a population of 583,776,[5] making it the 29th most populous city in the United States. Portland is Oregon's most populous city, and the third most populous city in the Pacific Northwest, after Seattle, Washington and Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Approximately 2,260,000 people live in the Portland metropolitan area (MSA),[6] the 23rd most populous in the United States.[6]

Portland was incorporated in 1851 and is the county seat of Multnomah County.[7] The city extends west into the Cedar Mill neighborhood in Washington County and south towards Lake Oswego in Clackamas County. With a commission-based government headed by a mayor and four other commissioners, the city and region are noted for strong land-use planning[8] and investment in light rail, supported by Metro, a distinctive regional government. Because of its public transportation networks and efficient land use planning, Portland has been referred to as one of the most environmentally friendly, or "green", cities in the world.[9]

Located in the Marine west coast climate region, Portland has a climate marked by warm, dry summers and wet but mild winters. This climate is ideal for growing roses, and for more than a century, Portland has been known as "The City of Roses"[10][11] with many rose gardens—most prominently the International Rose Test Garden. The city is also known for its large number of microbreweries and microdistilleries, as well as its coffee enthusiasm. It is also the home of the Timbers MLS team and the Trail Blazers NBA team.

Contents

History

Main article: History of Portland, OregonThe land today occupied by Multnomah County was inhabited for centuries by two bands of Upper Chinook Indians. The Multnomah people settled on and around Sauvie Island and the Cascades Indians settled along the Columbia Gorge. These groups fished and traded along the river and gathered berries, wapato and other root vegetables. The nearby Tualatin Plains provided prime hunting grounds.[12] The later settlement of Portland started as a spot known as "the clearing,"[13] which was on the banks of the Willamette about halfway between Oregon City and Fort Vancouver. In 1843, William Overton saw great commercial potential for this land but lacked the funds required to file a land claim. He struck a bargain with his partner, Asa Lovejoy of Boston, Massachusetts: for 25¢, Overton would share his claim to the 640 acres (2.6 km2) site. Overton later sold his half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove of Portland, Maine. Pettygrove and Lovejoy each wished to name the new city after his respective home town. In 1845, this controversy was settled with a coin toss, which Pettygrove won in a series of two out of three tosses.[14] The coin used for this decision, now known as the Portland Penny, is on display in the headquarters of the Oregon Historical Society.

At the time of its incorporation on February 8, 1851 Portland had over 800 inhabitants,[15] a steam sawmill, a log cabin hotel, and a newspaper, the Weekly Oregonian. By 1879, the population had grown to 17,500.[16] The city merged with Albina and East Portland in 1891, and annexed the cities of Linnton and St. Johns in 1915.

Portland's location, with access both to the Pacific Ocean via the Willamette and the Columbia rivers and to the agricultural Tualatin Valley via the "Great Plank Road" through a canyon in the West Hills (the route of current-day U.S. Route 26), gave it an advantage over nearby ports, and it grew very quickly.[17] It remained the major port in the Pacific Northwest for much of the 19th century, until the 1890s, when Seattle's deepwater harbor was connected to the rest of the mainland by rail, affording an inland route without the treacherous navigation of the Columbia River.

Nicknames

Main article: Nicknames of Portland, OregonThe most common nickname for Portland is The City of Roses,[18] and this became the city's official nickname in 2003.[19] Other nicknames include Stumptown,[20] Bridgetown,[21] Rip City,[22] Little Beirut,[1] Beervana[23][24] or Beertown,[25] P-Town,[19][26] Soccer City USA,[27][28][29][30] Portlandia, and the metonymous PDX.

Geography

The Willamette River runs through the center of the city, while Mount Tabor (center) rises on the city's east side. Mount Saint Helens (left) and Mount Hood (right center) are visible from many places in the city. Topography

Portland lies at the northern end of Oregon's most populated region, the Willamette Valley. However, as the metropolitan area is culturally and politically distinct from the rest of the valley, local usage often excludes Portland from the valley proper. Although almost all of Portland lies within Multnomah County, small portions of the city lie within Clackamas and Washington counties with mid-2005 populations estimated at 785 and 1,455, respectively. The Willamette River runs north through the city center, separating the east and west sections of the city before veering northwest to join with the Columbia River (which separates the state of Washington from the state of Oregon) a short distance north of the city.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 145.4 square miles (377 km2). 134.3 square miles (348 km2) of it is land and 11.1 square miles (29 km2), or 7.6%, is water.[31]

Portland lies on top of an extinct Plio-Pleistocene volcanic field known as the Boring Lava Field.[32] The Boring Lava Field includes at least 32 cinder cones such as Mount Tabor,[33] and its center lies in Southeast Portland. The dormant but potentially active volcano Mount Hood to the east of Portland is easily visible from much of the city during clear weather. The active volcano Mount Saint Helens to the north in Washington is visible in the distance from high-elevation locations in the city and is close enough to have dusted the city with volcanic ash after an eruption on May 18, 1980.[34] Mount Adams, another prominent volcano in Washington state to the northeast of Portland, is also visible from parts of the city.

Climate

Portland experiences a temperate climate that is usually described as oceanic with mild, damp winters and relatively dry, warm summers. Like much of the Pacific Northwest, according to the Köppen climate classification it falls within the cool, dry-summer subtropical zone (Csb), also referred to as cool-summer Mediterranean, because of its relatively dry summers.[35] Other climate classification systems, such as Trewartha, place it firmly in the Oceanic zone (Do).[36]

Summers in Portland are warm, sunny and rather dry, with August, the warmest month, averaging 79.7 °F (26.5 °C), and much larger day-night variation than in winter. Because of its inland location and when there is an absence of a sea breeze, heatwaves occur (in particular during the months of July and August) with air temperatures sometimes rising over 100 °F (38 °C), but 90 °F (32 °C) is more commonplace, occurring 13 days per annum.[37] Winters are normally mild, and very moist, with January averaging 39.9 °F (4.4 °C). Lows, though usually above freezing, can reach that mark or below 37 nights per year, however.[37] Cold snaps are short-lived, and snowfall occurs no more than a few times per year, although the city has been known to see major snow and ice storms because of the cold air outflow from the Columbia River Gorge. The city's winter snowfall totals have ranged from just a trace on many occasions, to 60.9 inches (154.7 cm) in 1892–93. Spring can bring rather unpredictable weather, resulting from warm spells, to thunderstorms rolling off the Cascade Range. The rainfall averages an equivalent 37.5 inches (950 mm) per year in downtown Portland, spread over 155 days a year. The lowest temperature ever recorded in Portland was −3 °F (−19 °C), set on February 2, 1950.[38] The highest temperature ever recorded was 107 °F (42 °C), set on July 30, 1965 as well as August 8 and 10, 1981.[38] Temperatures of 100 °F (38 °C) have been recorded in each of the months from May through September.[38]

Climate data for Portland, Oregon (PDX) Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Record high °F (°C) 63

(17)71

(22)80

(27)90

(32)103

(39)101

(38)107

(42)108

(42)105

(41)92

(33)73

(23)65

(18)108

(42)Average high °F (°C) 45.6

(7.6)50.3

(10.2)55.7

(13.2)60.5

(15.8)66.7

(19.3)72.7

(22.6)79.3

(26.3)79.7

(26.5)74.6

(23.7)63.3

(17.4)51.8

(11.0)45.4

(7.4)62.13

(16.74)Average low °F (°C) 34.2

(1.2)35.9

(2.2)38.6

(3.7)41.9

(5.5)47.5

(8.6)52.6

(11.4)56.9

(13.8)57.3

(14.1)52.5

(11.4)45.2

(7.3)39.8

(4.3)35.0

(1.7)44.78

(7.10)Record low °F (°C) −2

(−19)−3

(−19)11

(−12)29

(−1.7)29

(−1.7)39

(4)43

(6)44

(7)34

(1)26

(−3.3)13

(−11)6

(−14)−3

(−19)Precipitation inches (mm) 5.07

(128.8)4.18

(106.2)3.71

(94.2)2.64

(67.1)2.38

(60.5)1.59

(40.4).72

(18.3).93

(23.6)1.65

(41.9)2.88

(73.2)5.61

(142.5)5.71

(145)37.07

(941.6)Snowfall inches (cm) 1.6

(4.1)1.6

(4.1)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0).6

(1.5)1.3

(3.3)5.2

(13.2)Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) 17.2 15.8 17.2 15.3 12.8 8.8 4.4 4.8 7.5 11.4 18.9 18.3 152.4 Avg. snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) 1.0 1.1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 .4 1.3 3.8 Sunshine hours 86.8 118.7 192.2 222.0 275.9 291.0 331.7 297.6 237.0 151.9 78.0 65.1 2,347.9 Source no. 1: NOAA (1971–2000)[37] Source no. 2: HKO (sun, 1961–1990)[39] Cityscape

Panorama of downtown Portland. Hawthorne Bridge viewed from a dock on the Willamette River near the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI)

Panorama of downtown Portland at night. Viewed from across the Willamette River in SE Portland. See also: Architecture of Portland, Oregon, List of tallest buildings in Portland, Oregon, Downtown Portland, and Neighborhoods of Portland, OregonPortland straddles the Willamette River near its confluence with the Columbia River. The denser and earlier-developed west side is mostly hemmed in by the nearby West Hills (Tualatin Mountains), though it extends over them to the border with Washington County. The flatter east side fans out for about 180 blocks, until it meets the suburb of Gresham. Rural Multnomah County lies farther east. In 1891 the cities of Portland, Albina, and East Portland were consolidated, and duplicate street names were given new names. The "great renumbering" on September 2, 1931 standardized street naming patterns, and changed house numbers from 20 per block to 100 per block. It divided Portland into five sections: Southwest, Southeast, Northwest, North, and Northeast. Burnside St. divides north and south, and the Willamette River divides east and west. The river curves west five blocks north of Burnside and in place of it, Williams Ave. is used as a divider. The North section lies between Williams Ave. and the Willamette River to the west.

On the west side, the RiverPlace, John's Landing and South Waterfront Districts lie in a "sixth quadrant" where addresses go higher from west to east toward the river. This "sixth quadrant" is roughly bounded by Naito Parkway and Barbur Boulevard to the west, Montgomery Street to the north and Nevada Street to the south. East-West addresses in this area are denoted with a leading zero (instead of a minus sign). This means 0246 SW California St. is not the same as 246 SW California St. Many mapping programs are unable to distinguish between these two different addresses.

Parks and gardens

A panoramic view of the International Rose Test Garden

A panoramic view of the International Rose Test Garden

Tom McCall Waterfront Park seen from the north

Tom McCall Waterfront Park seen from the north Main article: List of parks in Portland, Oregon

Main article: List of parks in Portland, OregonPortlanders are proud of Portland's parks and its legacy of preserving open spaces. Parks and greenspace planning date back to John Charles Olmsted's 1903 Report to the Portland Park Board. In 1995, voters in the Portland metropolitan region passed a regional bond measure to acquire valuable natural areas for fish, wildlife, and people. Ten years later, more than 8,100 acres (33 km2) of ecologically valuable natural areas had been purchased and permanently protected from development.[40]

Portland is one of only three cities in the contiguous U.S. with extinct volcanoes within its boundaries (besides Jackson, Mississippi and Bend, Oregon). Mount Tabor Park is known for its scenic views and historic reservoirs.[41]

Forest Park is the largest wilderness park within city limits in the United States, covering more than 5,000 acres (2,023 ha). Portland is also home to Mill Ends Park, the world's smallest park (a two-foot-diameter circle, the park's area is only about 0.3 square m). Washington Park is just west of downtown, and is home to the Oregon Zoo, the Portland Japanese Garden, and the International Rose Test Garden.

Tom McCall Waterfront Park runs along the west bank of the Willamette for the length of downtown. The 37-acre (15 ha) park was built in 1974 after Harbor Drive was removed and now hosts large events throughout the year. Portland's downtown features two groups of contiguous city blocks dedicated for park space: the North and South Park Blocks.

Tryon Creek State Natural Area is one of three Oregon State Parks in Portland and the most popular; its creek has a run of steelhead. The other two State Parks are Willamette Stone State Heritage Site located in the West Hills and the Government Island State Recreation Area located in the Columbia River near Portland International Airport.

Culture and contemporary life

See also: List of fiction set in OregonPortland is often awarded the "Greenest City in America", and ranks among the world's top 10 greenest cities. Popular Science has continued to award Portland the title of the Greenest City in America and Grist magazine lists it as the second greenest city in the world.[42][43] Portland is the home city of "the World's Oldest Teenage Drag Queen Pageant", the Rose Bud and Thorn Pageant, started in 1975 and modeled after the Imperial Sovereign Rose Court of Oregon.[44]

Entertainment and performing arts

See also: Music of Oregon The Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, home of the Oregon Symphony, among others

The Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, home of the Oregon Symphony, among others

Like most large cities, Portland has a range of classical performing arts institutions which include the Oregon Ballet Theatre, Oregon Symphony, Portland Opera and the Portland Youth Philharmonic. It also has quite a few stages similar to New York's Off Broadway or Off-Off-Broadway such as Portland Center Stage, Artists Repertory Theatre, Miracle Theatre, Stark Raving Theatre, and Tears of Joy Theatre. Portland hosts the world's only HP Lovecraft Film Festival[45] at the Hollywood Theatre.

Portland is home to famous bands such as The Kingsmen and Paul Revere & the Raiders, both famous for their associations with the song "Louie Louie". Other widely known musical groups include The Dandy Warhols, Everclear, Modest Mouse, Pink Martini, Sleater-Kinney, The Shins, Blitzen Trapper, The Decemberists, and the late Elliott Smith. The city's now-demolished Satyricon nightclub is well known for being the place where the late Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain and Hole frontwoman Courtney Love met each other; Love had grown up in Portland for most of her life.[46] In recent years, a number of indie music bands from Portland have been touring nationally.

Widely recognized animators who hail from Portland include Matt Groening (The Simpsons) , Will Vinton (Will Vinton's A Claymation Christmas Celebration) and Travis Knight (Coraline). Dan Steffan, cartoonist-illustrator for Heavy Metal and other magazines, lives in Portland.

Filmmaker Gus Van Sant (Good Will Hunting (1997), Milk (2008)) is also a Portland native. Actors from Portland include Sam Elliott and Sally Struthers.

Recent films set and shot in Portland include Extraordinary Measures, Body of Evidence, What the Bleep Do We Know!?,The Hunted, Twilight, Paranoid Park, Wendy and Lucy, Feast of Love, Untraceable, and Coraline . An unusual feature of Portland entertainment is the large number of movie theaters serving beer, often with second-run or revival films. A notable example of these "brew and view" theaters is The Bagdad Theater and Pub.

TV shows including Portlandia, Leverage, Under Suspicion, Grimm, Nowhere Man and Life Unexpected have been filmed in Portland.

Authors

Authors from Portland include science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin, famous for her Earthsea novels, Hainish Cycle and Orsinian Tales; transgressional fiction novelist Chuck Palahniuk, best known for his award-winning novel Fight Club; best-selling Christian author Don Miller; and Beverly Cleary, author of the famous series of children's books featuring Henry Huggins, his dog Ribsy, Beatrice "Beezus" Quimby and Ramona Quimby. Klickitat Street, where Cleary's characters live, is an actual street in northeast Portland. Statues of the characters stand in nearby Grant Park.

Portland is home to a number of independent, small graphic novel publishers such as Dark Horse Comics and Oni Press,[47] as well as comic book artists and writers such as Brian Michael Bendis and Farel Dalrymple.

Tourism

Portland is home to a diverse array of artists and arts organizations, and was named in 2006 by American Style magazine as the tenth best Big City Arts Destination in the U.S.

The Portland Art Museum owns the city's largest art collection and presents a variety of touring exhibitions each year. With the recent addition of the Modern and Contemporary Art wing it became one of the United States' twenty-five largest museums. Art galleries abound downtown and in the Pearl District, as well as in the Alberta Arts District and other neighborhoods throughout the city.

The Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) is located on the east bank of the Willamette River across from downtown Portland, and contains a variety of hands-on exhibits covering the physical sciences, life science, earth science, technology, astronomy, and early childhood education. OMSI also has an OMNIMAX Theater and is home to the USS Blueback submarine, used in the film The Hunt for Red October.

Portland is also home to Portland Classical Chinese Garden, an authentic representation of a Suzhou-style walled garden.

Portlandia, a statue on the west side of the Portland Building, is the second-largest hammered-copper statue in the U.S. (after the Statue of Liberty). Portland's public art is managed by the Regional Arts & Culture Council.

Powell's City of Books, whose downtown multistory building at the intersection of Burnside and 10th Street occupies an entire city block, claims to be the largest independent bookstore in the United States and the largest bookstore west of the Mississippi River. Their specialty computer and science bookstore recently moved into a new location across the street.

The Portland Rose Festival takes place annually in June and includes two parades, dragon boat races, carnival rides at Tom McCall Waterfront park, and dozens of other events.

Washington Park, in the West Hills, is home to some of Portland's most popular recreational sites, including the Oregon Zoo, the Portland Japanese Garden, the World Forestry Center, and the Hoyt Arboretum.

Portland hosts a number of festivals throughout the year in celebration of beer and brewing, including the Oregon Brewers Festival. Held each summer during the last full weekend of July, it is the largest outdoor craft beer festival in North America with over 70,000 attendees in 2008.[48] Other major beer festivals throughout the calendar year include the Spring Beer and Wine Festival in April, the North American Organic Brewers Festival in June, the Portland International Beerfest in July,[49] and the Holiday Ale Festival in December.

Shopping

Portland has many options for shopping. Some of the well known shopping areas are Downtown Portland, Nob Hill (NW 21st & 23rd Avenues), Pearl District, and the Lloyd District. Major department stores in downtown include Nordstrom, Macy's, and Mario's. The major malls in the metropolitan area are Bridgeport Village, Washington Square, Clackamas Town Center, Lloyd Center, Vancouver Mall, and Pioneer Place. Another destination is the Portland Saturday Market, a town bazaar-like environment where many kinds of goods are sold from Artisan Crafts to Tibetan Imports, reflecting the many cultures of Portland. The Saturday Market is open every weekend from March through Christmas.

Breweries

Portland is well-known for its microbrewery beer.[50] Oregon Public Broadcasting has documented Portland's role in the microbrew revolution in the United States in a report called Beervana.[51] Some illustrate Portlanders' interest in the beverage by an offer made in 1888 when local brewer Henry Weinhard volunteered to pump beer from his brewery into the newly dedicated Skidmore Fountain. Portland's modern abundance of microbreweries dates to the 1980s when state law was changed to allow consumption of beer on brewery premises. Brewery innovation was supported by the abundance of local ingredients, including two-row barley, over a dozen varieties of hops, and pure water from the Bull Run Watershed.

Portland is home to more than 40 breweries—more breweries than any other city in the world[52]—which is partially responsible for CNBC naming Portland the best city for happy hour in the U.S.[53] The McMenamin brothers alone have over thirty brewpubs, distilleries, and wineries scattered throughout the metropolitan area, several in renovated cinemas and other historically significant buildings otherwise destined for demolition. Other notable Portland brewers include Widmer Brothers, BridgePort, and Hair of the Dog, as well as numerous smaller, quality brewers. In 1999, author Michael "Beerhunter" Jackson called Portland a candidate for the beer capital of the world because the city boasted more breweries than Cologne, Germany. The Portland Oregon Visitors Association promotes "Beervana" and "Brewtopia" as nicknames for the city.[54] In mid-January 2006, Mayor Tom Potter officially gave the city a new nickname: Beertown.[55]

Cuisine

Portland has a growing restaurant scene, and among three nominees, was recognized by the Food Network Awards as their "Delicious Destination of the Year: A rising city with a fast-growing food scene" for 2007.[56]

The New York Times also spotlighted Portland for its burgeoning restaurant scene in the same year.[57] Travel + Leisure ranked Portland No. 9 among all national cities in 2007.[58] The city is also known for being the most vegetarian-friendly city in America.[59]

Portland has been named the best city in the world for street food by several publications, including U.S. News[60] and CNN.[61] Food cart pods spread throughout the city have come to define the scene, appearing frequently on television programs & becoming popular destinations themselves.

In addition to beer, Portland has become known as a premier coffee destination in the Pacific Northwest. Yelp.com lists more than 20 coffee houses in Portland with 4.5-5 star ratings.[62] The city is home to the original Stumptown Coffee Roasters, well-known by aficionados as one of the nation's highest quality direct-trade roasteries,[63] as well as dozens of other micro-roasteries and cafes.

Sports

Main article: Sports in Portland, Oregon The Rose Garden, home of the Portland Trail Blazers.

The Rose Garden, home of the Portland Trail Blazers.

Portland is home to two major league teams: the Portland Timbers of Major League Soccer and the Portland Trail Blazers of the National Basketball Association.[64] The city is also home to a number of minor league teams.

Running is a popular sport in the metropolitan area, which hosts the Portland Marathon and much of the Hood to Coast Relay, the world's largest (by number of participants) long-distance relay race. The city is home to the Oregon Track Club, which includes American record holders Chris Solinsky, Alan Webb, and Shalane Flanagan. Skiing and snowboarding are also highly popular, with a number of nearby resorts on Mount Hood, including year-round Timberline Lodge.

Portland was formerly home to the Portland Rosebuds of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, the first professional sports team in Oregon and the first professional hockey team in the United States. The Rosebuds played in the 1916 Stanley Cup Finals, the first American team to do so.

The city also has one of the most active bicycle racing scenes in the United States. The Oregon Bicycle Racing Association sanctions hundreds of bicycling events each year. Weekly events at Alpenrose Velodrome and Portland International Raceway allow for racing nearly every night of the week March through September, and cyclocross races September through December, such as the Cross Crusade, can have over 1,000 riders and boisterous spectators.

Additionally, the Portland metro area has its own cricket league, the Oregon Cricket League. The league hosts two formats.[65][66]

Portland has two Division I college sports teams, the University of Portland Pilots and the Portland State Vikings. Both universities field teams in numerous sports, including soccer, baseball, basketball, and football. The University of Portland plays at Joe Etzel Field, the Clive Charles Soccer Complex, and the Chiles Center. Portland State University plays at the Stott Center and Jeld-Wen Field. In addition, Lewis & Clark College fields several sports teams that compete in NCAA Division III.

Club Sport League League championships Home venue Founded Portland Trail Blazers Basketball National Basketball Association 1 (1976-77) Rose Garden 1970 Portland Timbers Soccer Major League Soccer 0 Jeld-Wen Field 1975 Portland Winterhawks Ice hockey Western Hockey League 2 (1982–83, 1997–98) Rose Garden 1976 Media

Main article: Media in Portland, OregonThe Oregonian is the only daily general-interest newspaper serving Portland. It also circulates throughout the state and in Clark County, Washington.

Smaller local newspapers, distributed free of charge in newspaper boxes and at venues around the city, include Portland Tribune (general-interest paper published on Thursdays), Willamette Week (general-interest alternative weekly published on Wednesdays), The Portland Mercury (another weekly, targeted at younger urban readers published on Thursdays), and The Asian Reporter (a weekly covering Asian news, both international and local).

Portland Indymedia is one of the oldest and largest Independent Media Centers. The Portland Alliance, a largely anti-authoritarian progressive monthly, is the largest radical print paper in the city. Just Out, published in Portland twice monthly, is the region's foremost LGBT publication. A biweekly paper, Street Roots, is also sold within the city by members of the homeless community.

The Portland Business Journal, a weekly, covers business-related news, as does The Daily Journal of Commerce. Portland Monthly is a monthly news and culture magazine. The Bee, over 105 years old, is another neighborhood newspaper serving the inner southeast neighborhoods.

Portland is well served by television and radio.

Economy

Portland's location is beneficial for several industries. Relatively low energy cost, accessible resources, North-South and East-West Interstates, international air terminals, large marine shipping facilities, and both west coast intercontinental railroads are all economic advantages.[67] The US consulting firm Mercer, in a 2009 assessment "conducted to help governments and major companies place employees on international assignments", ranked Portland 42nd worldwide in quality of living; the survey factored in political stability, personal freedom, sanitation, crime, housing, the natural environment, recreation, banking facilities, availability of consumer goods, education, and public services including transportation.[68]

The city's history of attracting and retaining company headquarters is mixed. Major businesses such as Willamette Industries, Louisiana-Pacific, CH2M HILL, U.S. Bank, and Evraz North American (formerly known as Oregon Steel Mills), have moved headquarters out of the city, as have smaller companies such as Lucy Activewear and Northwest Pipe Company.[69] Examples of how the city has attracted a company's world, North American, or U.S. headquarters include Vestas Wind Systems, and sporting goods manufacturers Li-Ning Co., Hi-Tec Sports, KEEN, Inc. and Adidas.[69]

Other Portland based companies include advertising firm Wieden+Kennedy; financial services companies Umpqua Holdings Corporation and StanCorp Financial Group; data tracking firm Rentrak; utility providers PacifiCorp, NW Natural and Portland General Electric; communications provider Integra Telecom; restaurant chains McMenamins and McCormick & Schmick's; toolmaker Leatherman; and architectural firms ZGF Architects LLP and Boora Architects.

Real estate and construction

Video of Portland's Urban Growth boundary. The red dots indicate areas of growth between 1986 and 1996. (larger size)

Oregon's 1973 "urban growth boundary" law limits the boundaries for large scale development in each metropolitan area in Oregon.[70] This limits access to utilities such as sewage, water and telecommunications, as well as coverage by fire, police and schools.[70] Originally this law mandated that the city must maintain enough land within the boundary to provide an estimated 20 years of growth; however, in 2007 the legislature altered the law to require the maintenance of an estimated 50 years of growth within the boundary, as well as the protection of accompanying farm and rural lands.[71]

The growth boundary, along with efforts of the PDC to create economic development zones, has led to the development of a large portion of downtown, a large number of mid- and high-rise developments, and an overall increase in housing and business density.[72][73]

Manufacturing

Computer components manufacturer Intel is the Portland area's largest employer, providing jobs for more than 15,000 people, with several campuses to the west of central Portland in the city of Hillsboro.[67] The metro area is home to more than 1,200 technology companies.[67] This high density of technology companies has led to the nickname Silicon Forest being used to describe the Portland area, a reference to the abundance of trees in the region and to the Silicon Valley region in Northern California.

Portland is home to the North American headquarters for Adidas, while the metropolitan area serves as the headquarters for Nike, FLIR Systems, Columbia Sportswear, and TriQuint Semiconductor, among others. Nike and Portland based Precision Castparts are the only two Fortune 500 companies headquartered in Oregon. Other manufacturing companies based in Portland include Freightliner Trucks, Zidell Companies, The Collins Companies, while Western Star Trucks builds their trucks in the city.

The steel industry's history in Portland predates World War II. By the 1950s, the steel industry became the city's number one industry for employment.[74] The steel industry thrives in the region, with Schnitzer Steel Industries, a prominent steel company, shipping a record 1.15 billion tons of scrap metal to Asia during 2003.[74] Other heavy industry companies include ESCO Corporation and Oregon Steel Mills.

Logistics

Portland is the largest shipper of wheat in the United States,[75][76] and is the second largest port for wheat in the world.[77] The marine terminals alone handle over 13 million tons of cargo per year, and is home to one of the largest commercial dry docks in the country.[78][79] The Port of Portland is the third largest U.S. port on the west coast, though it is located about 80 miles (130 km) upriver.[67][79]

Transportation

MAX Light Rail is the centerpiece of the city's public transportation systemPortland Streetcar runs north-south through DowntownPortland Aerial Tram connects the South Waterfront district with OHSUMain article: Transportation in Portland, OregonThe Portland metropolitan area has transportation services common to major U.S. cities, though Oregon's emphasis on proactive land-use planning and transit-oriented development within the urban growth boundary means that commuters have multiple well-developed options. A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Portland 12th most walkable of fifty largest U.S. cities.[80] Some Portlanders use mass transit for their daily commute. In 2008, 12.6% of all commutes in Portland were on public transit.[81] TriMet operates most of the region's buses and the MAX (short for Metropolitan Area Express) light rail system, which connects the city and suburbs. Westside Express Service, or WES, opened in February 2009 as commuter rail for Portland's western suburbs, linking Beaverton and Wilsonville. The Portland Streetcar operates from the south waterfront, through Portland State University and north to nearby homes and shopping districts. The Streetcar line will add 3.3 miles of tracks on the east side of the Willamette River in the fall of 2012.[82] The line will complete a loop to the tracks on the west side of the river once the new Portland-Milwaukie Light Rail Bridge is completed in 2013.[83] Within the Free Rail Zone, a designated geographic area centered in downtown, rides on TriMet's MAX and streetcar systems are free. Fifth and Sixth avenues within downtown comprise the Portland Transit Mall, two streets devoted primarily to bus and light rail traffic with limited automobile access. Intense public transit development continues as two light rail lines are under construction, as well as a new downtown transit mall linking several transit options. TriMet also provides real-time tracking of buses and trains with its TransitTracker and even makes the data available to software developers so they can create customized tools of their own.[84]

I-5 connects Portland with the Willamette Valley, Southern Oregon, and California to the south and with Washington to the north. I-405 forms a loop with I-5 around the central downtown area of the city and I-205 is a loop freeway route on the east side which connects to the Portland International Airport. US 26 supports commuting within the metro area and continues to the Pacific Ocean westward and Mount Hood and Central Oregon eastward. US 30 has a main, bypass, and business route through the city extending to Astoria, Oregon to the west; through Gresham, Oregon, and the eastern exurbs, and connects to I-84, traveling towards Boise, Idaho.

Portland's main airport is Portland International Airport, located about 20 minutes by car (40 minutes by MAX) northeast of downtown. In addition Portland is home to Oregon's only public use heliport, the Portland Downtown Heliport. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Portland at Union Station on three routes. Long-haul train routes include the Coast Starlight (with service from Los Angeles to Seattle) and the Empire Builder (with service from Portland to Chicago.) The Amtrak Cascades commuter trains operate between Vancouver, British Columbia and Eugene, Oregon, and serve Portland several times daily.

The city is particularly supportive of urban bicycling and has been recognized by the League of American Bicyclists among others for its network of on street bicycling facilities and other bicycle-friendly services.[85] It ranks highly among the most bicycle friendly cities in the world.[86] The Bicycle Transportation Alliance sponsors an annual Bicycle Commute Challenge, in which thousands of commuters compete for prizes and recognition based on the length and frequency of their commutes.[87] Approximately 8% of commuters bike to work, the highest proportion of any major U.S. city and about 10 times the national average.[88]

Car sharing through Zipcar and U Car Share is available to residents of the city and some inner suburbs. Portland has a commuter aerial cableway, the Portland Aerial Tram, which connects the South Waterfront district on the Willamette River to the Oregon Health & Science University campus on Marquam Hill above.

Portland has five indoor skateparks and is home to historically significant Burnside Skatepark. Gabriel Skatepark is the most recent, which opened on July 12, 2008. Another fourteen are in the works.[89] The Wall Street Journal stated Portland "may be the most skateboard-friendly town in America."[90]

Law and government

See also: Government of Portland, OregonThe city of Portland is governed by the Portland City Council, which includes the Mayor, four Commissioners, and an auditor. Each is elected citywide to serve a four year term. The auditor provides checks and balances in the commission form of government and accountability for the use of public resources. In addition, the auditor provides access to information and reports on various matters of city government.

The city's Office of Neighborhood Involvement serves as a conduit between city government and Portland's 95 officially recognized neighborhoods. Each neighborhood is represented by a volunteer-based neighborhood association which serves as a liaison between residents of the neighborhood and the city government. The city provides funding to neighborhood associations through seven district coalitions, each of which is a geographical groupings of several neighborhood associations. Most (but not all) neighborhood associations belong to one of these district coalitions.

Portland and its surrounding metropolitan area are served by Metro, the United States' only directly elected metropolitan planning organization. Metro's charter gives it responsibility for land use and transportation planning, solid waste management, and map development. Metro also owns and operates the Oregon Convention Center, Oregon Zoo, Portland Center for the Performing Arts, and Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center.

The Multnomah County government provides many services to the Portland area, as do Washington and Clackamas counties to the west and south.

Portland strongly favors the Democratic Party. Although local elections are nonpartisan, most of the city's elected officials are Democrats.

Portland's delegation to the Oregon Legislative Assembly is entirely Democratic. In the current 76th Oregon Legislative Assembly, which first convened in 2011, four state Senators represent Portland in the state Senate: Diane Rosenbaum (District 21), Chip Shields (District 22), Jackie Dingfelder (District 23), and Rod Monroe (District 24), all Democrats. Portland sends six Representatives to the state House of Representatives: Jules Bailey (District 42), Lew Frederick (District 43), Tina Kotek (District 44), Michael Dembrow (District 45), Ben Cannon (District 46), and Jefferson Smith (District 47), also all Democrats.

Portland's federal representation in the United States House of Representatives is split between three congressional districts. Most of the city is in the 3rd District, represented by Earl Blumenauer, who served on the city council from 1986 until his election to Congress in 1996. Most of the city west of the Willamette River is part of the 1st District, represented by David Wu. A small portion of the city is in the 5th District, represented by Kurt Schrader. All three are Democrats. A Republican has not represented a significant portion of Portland in the U.S. House of Representatives since 1975. Both of Oregon's senators, Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, are from Portland and are also both Democrats.

Sam Adams, the current mayor of Portland, became the city's first openly gay mayor in 2009.[91] In 2004, 59.7 percent of Multnomah County voters cast ballots against Oregon Ballot Measure 36, which amended the Oregon Constitution to prohibit recognition of same-sex marriages. The measure passed with 56.6% of the statewide vote. Multnomah County is one of two counties where a majority voted against the initiative; the other is Benton County, which includes Corvallis, home of Oregon State University.[92]

On April 28, 2005, Portland became the only city in the nation to withdraw from a Joint Terrorism Task Force.[93][94]

Planning and development

The city consulted with urban planners as far back as 1903. Development of Washington Park and one of the country's finest greenways, the 40 Mile Loop, which interconnects many of the city's parks, began.

Portland is often cited as an example of a city with strong land use planning controls;[8] This is largely the result of statewide land conservation policies adopted in 1973 under Governor Tom McCall, in particular the requirement for an urban growth boundary (UGB) for every city and metropolitan area. The opposite extreme, a city with few or no controls, is typically illustrated by Houston, Texas.[95][96][97][98][99]

Portland's urban growth boundary, adopted in 1979, separates urban areas (where high-density development is encouraged and focused) from traditional farm land (where restrictions on non-agricultural development are very strict).[100] This was atypical in an era when automobile use led many areas to neglect their core cities in favor of development along interstate highways, in suburbs, and satellite cities.

The original state rules included a provision for expanding urban growth boundaries, but critics felt this wasn't being accomplished. In 1995, the State passed a law requiring cities to expand UGBs to provide enough undeveloped land for a 20 year supply of future housing at projected growth levels.[101]

The Portland Development Commission is a semi-public agency that plays a major role in downtown development; it was created by city voters in 1958 to serve as the city's urban renewal agency. It provides housing and economic development programs within the city, and works behind the scenes with major local developers to create large projects.

In the early 1960s, the PDC led the razing of a large Italian-Jewish neighborhood downtown, bounded roughly by the I-405 freeway, the Willamette River, 4th Avenue and Market street.

Mayor Neil Goldschmidt took office in 1972 as a proponent of bringing housing and the associated vitality back to the downtown area, which was seen as emptying out after 5 pm. The effort has had dramatic effects in the 30 years since, with many thousands of new housing units clustered in three areas: north of Portland State University (between the I-405 freeway, SW Broadway, and SW Taylor St.); the RiverPlace development along the waterfront under the Marquam (I-5) bridge; and most notably in the Pearl District (between I-405, Burnside St., NW Northrup St., and NW 9th Ave.).

The Urban Greenspaces Institute, housed in Portland State University Geography Department's Center for Mapping Research, promotes better integration of the built and natural environments. The institute works on urban park, trail, and natural areas planning issues, both at the local and regional levels.

In October 2009, the Portland City Council unanimously adopted a climate action plan that will cut the city's greenhouse gas emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.[102]

According to Grist magazine, Portland is the second most eco-friendly or "green" city in the world trailing only Reykjavík, Iceland.[103] In 2010, Move, Inc. placed Portland in its "top 10 greenest cities" list.[104][105]

Free speech

Because of strong free speech protections of the Oregon Constitution upheld by the Oregon Supreme Court Henry v. Oregon Constitution 1987 which specifically found that full nudity and lap dances in strip clubs are protected speech,[106] Portland is widely considered to have more strip clubs per capita than Las Vegas or San Francisco.[107][108][109] Portland has been titled as "Pornland" for its strip clubs, erotic massage parlors, and high rate of child sex trafficking.[110][111] The term was heavily used in 2010, but the term was referenced by Chuck Palahniuk in 2003.[112]

A judge dismissed charges against a nude bicyclist in November 2008 on the grounds that the city's annual World Naked Bike Ride "was a well-established tradition in Portland. The first instance occurred sometime around 1999 and had less than 7 participants; at the time it was jokingly referred to as "critical ass" (a play on Critical Mass bike rides). Participants would 'purchase' a bike from a local chain department store and then return it the next morning. It used to take place at midnight and lasted until the participants were stopped/arrested. The prankster aspect of it came in when the arresting officers didn't want to touch the naked cyclists in order to arrest them.[113] The 2009 Naked Bike Ride occurred without significant incident.[114] City police managed traffic intersections.[115] There were an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 participants. In June 2010 Portland's World Naked Bike Ride had an estimated 13,000 people.[116][117][118]

A state law prohibiting publicly insulting a person in a way likely to provoke a violent response was tested in Portland and struck down unanimously by the State Supreme Court as violating protected free speech and being overly broad.[119]

Demographics

As of 2000, there are an estimated 529,121 people residing in the city, organized into 223,737 households and 118,356 families. The population density is 4,228.38 people per square mile (1,655.31/km²). There are 237,307 housing units at an average density of 1,766.7 per square mile (682.1/km²). Population growth in the Portland metropolitan area has outpaced the national average during the last decade, with 2008 estimates showing an 80% chance of population growth in excess of 60% over the next 50 years.[71]

2010 Census data

The racial makeup of the city was 73.9% White (405,938), 8.8% Hispanic or Latino (of any race) (48,285), 7.8% Asian (42,785), 7.8% Black or African American (42,711), 2.8% Native American (15,523), 0.6% Pacific Islander (3,564), and 3.0% from other races (16,347).

The Marquam Bridge over the Willamette River, viewed from the southwest, atop Marquam Hill

The Marquam Bridge over the Willamette River, viewed from the southwest, atop Marquam Hill

Out of 223,737 households, 24.5% have children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.1% are married couples living together, 10.8% have a female householder with no husband present, and 47.1% are non-families. 34.6% of all households are made up of individuals and 9% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 2.3 and the average family size is 3.

The age distribution was 21.1% under the age of 18, 10.3% from 18 to 24, 34.7% from 25 to 44, 22.4% from 45 to 64, and 11.6% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 35 years. For every 100 females there are 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there are 95.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city is $40,146, and the median income for a family is $50,271. Males have a reported median income of $35,279 versus $29,344 reported for females. The per capita income for the city is $22,643. 13.1% of the population and 8.5% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 15.7% of those under the age of 18 and 10.4% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line. Figures delineating the income levels based on race are not available at this time.

However, though the population of the city is increasing, the total population of children is diminishing, which has put pressure on the public school system to close schools. A 2005 study found that Portland is now educating fewer children than it did in 1925, despite the city's population having almost doubled since then, and the city will have to close the equivalent of three to four elementary schools each year for the next decade.[122]

In 1940, Portland's African-American population was approximately 2,000 and largely consisted of railroad employees and their families.[123] During the war-time liberty ship construction boom, the need for workers drew many blacks to the city. The new influx of blacks settled in specific neighborhoods, such as the Albina district and Vanport. The May 1948 flood which destroyed Vanport eliminated the only integrated neighborhood, and an influx of blacks into the NE quadrant of the city continued.[123] At 7.90%, Portland's African American population is nearly four times the state average. Over two thirds of Oregon's African-American residents live in Portland.[123] As of the 2000 census, three of its high schools (Cleveland, Lincoln and Wilson) were over 70% white, reflecting the overall population, while Jefferson High School was 87% non-white. The remaining six schools have a higher number of non-whites, including blacks and Asians. Hispanic students average from 3.3% at Wilson to 31% at Roosevelt.[124]

With about 12,000 Vietnamese residing in the city proper, Portland has one of the largest Vietnamese populations in America per capita.[not in citation given][125] According to statistics there are 21,000 Pacific Islanders in Portland, making up 4% of the population.[126]

The city of Portland has the 7th highest LGBT population in the country, with 8.8% of residents identifying as homosexual, and the metro area ranks 4th in the nation at 6.1%.[127]

Racial history

Portland's population has been and remains predominantly white. In 2009, Portland had the fifth-highest percentage of white residents among the 40 largest U.S. metropolitan areas. A 2007 survey of the 40 largest cities in the U.S. concluded that Portland's urban core is the "whitest big city in the nation".[128] Some scholars have noted the Pacific Northwest as a whole is "one of the last Caucasian bastions of the United States".[129] While Portland's diversity was historically comparable to metro Seattle and Salt Lake City, those areas grew more diverse in the late 1990s and 2000s. Portland not only remains white, but migration to Portland is disproportionately white, at least partly because Portland is attractive to young college-educated Americans, a group which is overwhelmingly white.[128][130]

The racial demographics today are largely a result of historic policies and trends. The Oregon Territory banned African American immigration in 1849. In the 19th century, certain laws allowed the immigration of Chinese laborers but prohibited them from owning property or bringing their families.[128][131][132] The early 1920s saw the rapid growth of the Ku Klux Klan, which became very influential in Oregon politics, culminating in the election of Walter M. Pierce as governor.[131][132][133]

The largest influxes of minority populations occurred during World War II, as the African American population grew 10 times for wartime work.[128] After World War II, the Vanport flood in 1948 displaced many African Americans. As they resettled, redlining directed the displaced workers from the wartime settlement to neighboring Albina.[129][132][134] There and elsewhere in the Portland area, they experienced police hostility, lack of employment, and mortgage discrimination, leading to half the black population leaving after the war.[128] Widespread housing discrimination continues to affect the racial landscape today. A 2011 audit of landlords' renting practices by the Fair Housing Council of Oregon indicated that 64% of 50 leasing agents discriminated against Latino or black prospective tenants, compared with white prospective tenants. The Oregonian stated, "They were quoted higher rent and deposits, for example, or given additional fees, not offered applications or move-in specials, or shown inferior units."[135]

In the 1980s and 1990s, radical skinhead groups flourished in Portland.[132] During redevelopment of north Portland along the MAX Yellow Line, displacement of minorities occurred at a drastic rate. Out of 29 census tracts in north and northeast Portland, ten were majority nonwhite in 2000. By 2010, none of these tracts were majority nonwhite as gentrification drove the cost of living up.[136] However, Portland's African-American community still thrives in the north and northeast section of the city, mainly in the King Neighborhood.

Education

Main article: Education in Portland, OregonPortland is served by six public school districts and many private schools. Portland Public Schools is the largest school district. There are also many colleges and universities- the largest being Portland Community College, Portland State University, and Oregon Health & Science University. The city is also home to such private universities as the University of Portland, Reed College, and Lewis & Clark College.

Museums

Portland is home to many educational museums. They include:

Oregon Museum of Science and Industry

Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), which includes many hands on activities for adults and children. OMSI consists of five main halls, most of which, consist of smaller laboratories: Earth Science Hall, Life Science Hall, Turbine Hall, Science Playground, and Featured Exhibit Hall. The Featured Exhibit Hall has a new exhibit every few months. The laboratories are Chemistry, Physics, Technology, Life, Paleontology, and Watershed. OMSI has many other unique attractions, such as the USS Blueback (SS-581), the OMNIMAX Dome Theater, and OMSI's Kendall Planetarium. The USS Blueback was the last non-nuclear fast attack submarine to join the US Navy and OMSI offers daily tours.[137] The OMNIMAX Dome Theater is a variant of the IMAX motion picture format, where the movie is projected onto a domed projection surface. The projection surface at OMSI's OMNIMAX Dome Theater is 6,532 sq ft (606.8 m2). The OMNIMAX Theater uses the largest frame in the motion picture industry and the frames are ten times the size of the standard 35mm film.[138] OMSI's Kendall Planetarium is the largest and most technologically advanced planetarium in the Pacific Northwest.[139] OMSI is located at 1945 SE Water Ave. OMSI is built right up next to the river and is also conveniently located near the entrance to the Springwater Corridor and Eastbank Esplanade pedestrian and bike trails.

Portland Art Museum

The Portland Art Museum owns the city's largest art collection and presents a variety of touring exhibitions each year and with the recent addition of the Modern and Contemporary Art wing it became one of the United States' twenty-five largest museums.

Oregon History Museum

The Oregon History Museum was founded in 1898. The Oregon History Museum has a variety of books, film, pictures, artifacts, and maps dating back throughout Oregon's history. The Oregon History Museum has one of the most extensive collections of state history materials in the USA.

The Portland Children's Museum

The Portland Children's Museum is a museum specifically geared for early childhood development. This museum has many topics, and many of their exhibits rotate, to keep the information fresh. The Portland Children's Museum also supports a small charter school for elementary children.

Crime

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Uniform Crime Report in 2009, Portland ranked 53rd in violent crime out of the top 75 U.S. cities with a population greater than 250,000.[140] The murder rate in Portland over the last five years (2005–2009) has averaged 3.9 murders per 100,000 people per year, which is lower than the national average. For crimes other than murder, Portland is generally somewhat higher than the national average. According to the Portland Police, Killingsworth St., 82nd Ave., and the St. Johns Woods Apartments are the most dangerous areas of the city.[141] In October, 2009, the Forbes magazine rated Portland as the third safest city in America.[142][143]

Sister cities

Portland has nine sister cities:[144]

Ashkelon, Israel

Ashkelon, Israel Kaohsiung, Republic of China (Taiwan)

Kaohsiung, Republic of China (Taiwan) Ulsan, South Korea

Ulsan, South Korea Mutare, Zimbabwe

Mutare, Zimbabwe Guadalajara, Mexico

Guadalajara, Mexico

Khabarovsk, Russia

Khabarovsk, Russia Sapporo, Japan

Sapporo, Japan Suzhou, People's Republic of China

Suzhou, People's Republic of China Bologna, Italy

Bologna, Italy

Portland also has a "Friendship City" relationship with:Gallery

-

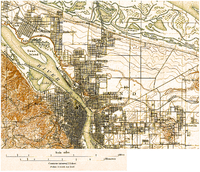

1897 topographic map of Portland shows streets, railroads, and significant differences in the Columbia Slough

-

MAX Light Rail and underground station at the Oregon Zoo

-

A view of the Willamette River from the Roof of the KOIN Center

See also

- List of people from Portland, Oregon

- 1972 Portland-Vancouver Tornado

- List of hospitals in Portland, Oregon

- Keep Portland Weird

References

- ^ a b McCall, William (August 19, 2003). "'Little Beirut' nickname has stuck". The Oregonian.

- ^ "Elected Officials". City of Portland, Oregon. 2007. http://www.portlandonline.com/index.cfm?c=25999. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. http://geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ a b "2010 Census profiles: Oregon cities alphabetically M-P" (PDF). Portland State University Population Research Center. http://www.pdx.edu/sites/www.pdx.edu.prc/files/media_assets/2010_PL94_cities_M-P.pdf. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "Portland U.S.'s 23rd-largest metro area - Portland Business Journal". Bizjournals.com. http://www.bizjournals.com/portland/blog/2011/06/portland-uss-23rd-largest-metro-area.html?ed=2011-06-24&s=article_du&ana=e_du_pub. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. http://www.naco.org/Counties/Pages/FindACounty.aspx. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ a b "The "Smart Growth" Debate Continues". Urban Mobility Corporation. May/June 2003. http://www.innobriefs.com/editor/20030423smartgrowth.html. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ Kate Sheppard (July 19, 2007). "15 Green Cities". Environmental News and Commentary. http://www.grist.org/article/cities3. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ "Portland, Oregon: Green City of Roses | Frommers.com". Frommers.com. http://www.frommers.com/articles/1721.html. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ "Portland – MSN Encarta". Portland – MSN Encarta. Encarta.msn.com. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761561539/portland.html. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Marschner, Janice (2008). of portland before europeans indians&f=false Oregon 1859: a spapshot in time. Timber Press. p. 187. ISBN 9780881928730. http://books.google.com/?id=1-UW6M_gw48C&pg=PA187&dq=history+of+portland+before+europeans+indians#v=onepage&q=history of portland before europeans indians&f=false.

- ^ Orloff, Chet (2004). "Maintaining Eden: John Charles Olmsted and the Portland Park System". Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 66: 114–119. doi:10.1353/pcg.2004.0006.

- ^ "Portland: The Town that was Almost Boston". Portland Oregon Visitors Association. http://www.travelportland.com/media/history.html. Retrieved November 18, 2006.

- ^ Gibson, Campbell (June 1998). Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990. U.S. Bureau of the Census – Population Division.

- ^ Loy, William G.; Stuart Allan, Aileen R. Buckley, James E. Meacham (2001). Atlas of Oregon. University of Oregon Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-87114-101-9.

- ^ "City keeps lively pulse." (Spencer Heinz, The Oregonian, January 23, 2001)

- ^ City Flower. City of Portland Auditor's Office – City Recorder Division.

- ^ a b Stern, Henry (June 19, 2003). "Name comes up roses for P-town: City Council sees no thorns in picking ‘City of Roses’ as Portland's moniker". The Oregonian.

- ^ "From Robin's Nest to Stumptown". End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center. http://www.endoftheoregontrail.org/road2oregon/sa33pdx.html. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ "The Water". Portland State University. Archived from the original on October 31, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20061031090707/http://www.pdx.edu/water.html. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ Baker, Nena (May 21, 1991). "R.I.P. FOR 'Rip City' Ruckus". The Oregonian: pp. A01

- ^ Engel, Mary (May 30, 2010). "Achieving Beervana in Portland, Ore.". Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/travel/la-tr-beer-20100530,0,767659.story. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ Terry, Lynne (May 29, 2010). "Beervana gets shout out in L.A. Times". The Oregonian. http://www.oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2010/05/beervana_gets_shout_out_in_la.html. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ "Portland – Beer Town USA | DRAFT Magazine". Draftmag.com. http://www.draftmag.com/beertowns/detail/portland. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ Hagestedt, Andre (April 7, 2009). "The Missing Oregon Coast: Waves After Dark". http://www.beachconnection.net/news/missin040709_147.php. Retrieved April 30, 2009. "I’m used to seeing that hint of dawn back in P-town, with my wretched habit of playing video games until 6 a.m"

- ^ "Portland is new Soccer City, USA". Eugene Register-Guard. United Press International (Eugene, Oregon). August 13, 1975. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=II4QAAAAIBAJ&sjid=J-ADAAAAIBAJ&pg=5122,3289171&hl=en. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (November 6, 2008). "Seeking Help to Bring an M.L.S. Team to Portland". The New York Times (New York, New York). http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/07/sports/soccer/07franchise.html?ref=soccer. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (September 18, 2009). "Portland's ugly road to MLS status". Sports Illustrated. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2009/soccer/09/17/portland.timbers/index.html. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ Dure, Beau (August 26, 2009). "Portland Timbers show bark, bite as they prepare to join MLS". USA Today (McLean, Virginia). http://www.usatoday.com/sports/soccer/2009-08-25-portland-timbers_N.htm. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. http://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/gazette.html. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "The Boring Lava Field, Portland, Oregon". USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory. http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/Oregon/BoringLavaField/description_boring_lava.html. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ "Mount Tabor Cinder Cone, Portland, Oregon". USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory. http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/Oregon/BoringLavaField/VisitVolcano/mount_tabor.html. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ Nokes, R. Gregory (December 4, 2000). "History, relived saved from St. Helens by a six-pack of Fresca". The Oregonian: p. 17.

- ^ Kottek, M.; J. Grieser, C. Beck, B. Rudolf, and F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. http://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/pics/kottek_et_al_2006.gif. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ "GLOBAL ECOLOGICAL ZONING FOR THE GLOBAL FOREST RESOURCES ASSESSMENT 2000". Fao.org. http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/ad652e/ad652e07.htm. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Climatography of the United States No. 20: 1971–2000". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://cdo.ncdc.noaa.gov/climatenormals/clim20/or/356751.pdf. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c "NOW Data-NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.wrh.noaa.gov/pqr/climate/pdx_clisummary.php. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Portland, OR". Hong Kong Observatory. http://www.weather.gov.hk/wxinfo/climat/world/eng/n_america/us/Portland_e.htm. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ Houck, Mike. "Metropolitan Greenspaces: A Grassroots Perspective". Audubon Society of Portland. Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20061003201150/http://www.audubonportland.org/conservation_advocacy/urbanconservation/metro_greenspaces. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ "Mount Tabor Park". Portland Parks & Recreation. http://www.portlandonline.com/parks/finder/index.cfm?action=ViewPark&PropertyID=275. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ "America's 50 Greenest Cities". http://www.popsci.com/environment/article/2008-02/americas-50-greenest-cities?page=1. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "15 Green Cities". http://www.grist.org/article/cities3/. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "Imperial Sovereign Rose Court official site". http://www.rosecourt.org/. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ "Lovecraft Film Festival Official Site". http://www.hplfilmfestival.com/. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- ^ "Kurt Cobain". Biography.com. http://www.biography.com/articles/Kurt-Cobain-9542179?print. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ "Stumptown Comics Fest and Zine Library Group Unite". bookreporter.com. http://www.graphicnovelreporter.com/content/stumptown-comics-fest-and-zine-library-group-unite-feature-stories. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ "OregonLive blog". http://blog.oregonlive.com/thebeerhere/2008/07/2008_obf_biggest_ever_say_orga.html.

- ^ Distefano, Anne Marie (July 8, 2005). "Brewers, beer lovers get many reasons to raise a glass". Portland Tribune. http://www.portlandtribune.com/features/story.php?story_id=30717.

- ^ Merrill, Jessica (January 13, 2006). "In Oregon, It's a Brew Pub World". The New York Times. http://travel.nytimes.com/2006/01/13/travel/escapes/13beer.html. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ^ "Oregon Experience: Beervana" (video). http://www.opb.org/programs/oregonexperiencearchive/beervana/player.php. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ^ Ransom, Diana (September 16, 2011). "Why Portland's Beer Economy is 'Hoppy'". Entrepreneur. http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/220319. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Paul Toscano (September 8, 2010). "America's Best Cities for Happy Hour". CNBC. http://www.cnbc.com/id/39057498?slide=13. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ^ "Portland: The center of the beer universe". Portland Oregon Visitors Association. http://www.travelportland.com/media/mbmedkit/mb_beer.html. Retrieved November 18, 2006.

- ^ "Portland lifts a glass to its new name". KOIN 6 News. January 12, 2006. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070213215818/http://koin.com/Global/story.asp?S=5932394. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

- ^ "TV : Food Network Awards : Food Network Awards Winners : Food Network". Foodnetwork.com. http://www.foodnetwork.com/food/show_aw/text/0,3151,FOOD_28456_61089,00.html. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ Asimov, Eric (Published: September 26, 2007). "In Portland, a Golden Age of Dining and Drinking – New York Times". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/26/dining/26port.html?pagewanted=3&_r=1. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ "America's Favorite Cities 2007 | Food/Dining | Food/Dining (Overall) | Travel + Leisure". Travelandleisure.com. http://www.travelandleisure.com/afc/2007/category/6. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ "GoVeg.com // Features // North America's Most Vegetarian-Friendly Cities! // Portland, Oregon". Goveg.com. http://www.goveg.com/f-vegcities-portland.asp. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ "World's Best Street Food". U.S. News. http://travel.usnews.com/features/Worlds_Best_Street_Food/.

- ^ "World's Best Street Food". CNN Travel. http://articles.cnn.com/2010-07-19/travel/worlds.best.street.food_1_street-food-arepas-locals?_s=PM:TRAVEL.

- ^ "Portland Coffee Shops". Yelp.com. http://www.yelp.com/c/portland/coffee. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- ^ Strand, Oliver (September 16, 2009). "A Seductive Cup". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/16/dining/reviews/16brief-001.html. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- ^ Neyer, Rob (August 21, 2003). "Though not perfect, Portland is a viable city for baseball". ESPN. http://sports.espn.go.com/mlb/columns/story?columnist=neyer_rob&id=1600284. Retrieved January 6, 2009. "Portland is the largest metropolitan area with just one major professional sports team (the Trail Blazers)."

- ^ "Oregon Sports Authority " Blog Archive Not every sport requires a ball". Oregonsports.org. July 3, 2008. http://www.oregonsports.org/not-every-sport-requires-a-ball/. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to OCL". Oregon Cricket League. http://www.oregoncricketleague.org. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Portland: Economy – Major Industries and Commercial Activity". http://www.city-data.com/us-cities/The-West/Portland-Economy.html. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Quality of Living global city rankings 2009 – Mercer survey". Mercer. April 28, 2009. http://www.mercer.com/referencecontent.htm?idContent=1173105. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ^ a b "Notable Portland HQ departures". Portland Business Journal. January 20, 2011. http://www.bizjournals.com/portland/news/2011/01/20/other-hq-companies-that-have-left-town.html?s=print. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ a b "Metro: Urban growth boundary". http://www.metro-region.org/index.cfm/go/by.web/id/277. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ a b Law, Steve (May 29, 2008). "Metro takes long view of growth". Portland Tribune. http://www.portlandtribune.com/news/story.php?story_id=121200846357363500. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Portland – SkyscraperPage". http://skyscraperpage.com/cities/?cityID=29. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "OLMIS – Portland Metro Area: A Look at Recent Job Growth". http://www.qualityinfo.org/olmisj/ArticleReader?itemid=00005735. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ a b "Steel Industry". http://www.history.pdx.edu/guildslake/industry/steel1.htm. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "Next stop: Port of Portland". January 7, 2009. http://learfieldcreative.typepad.com/brownfield/2009/01/next-stop-port-of-portland-.html. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ "Port of Portland's Statement of Need". Center for Columbia River History. http://www.ccrh.org/comm/slough/primary/stmntofnd.htm. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ "White House press release: The Columbia River Channel Deepening Project, August 13, 2004". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. August 13, 2004. http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2004/08/20040813-1.html. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ "Cascade General, Inc". http://www.answers.com/topic/cascade-general-inc?cat=biz-fin. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ a b "Portfolio" (PDF). http://www.portofportland.com/PDFPOP/Portfolio_06_07.pdf. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ "2011 City and Neighborhood Rankings". Walk Score. 2011. http://www.walkscore.com/rankings/cities/. Retrieved Aug 28, 2011.

- ^ "American Community Survey 2006, Table S0802". U.S. Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/STGeoSearchByListServlet?ds_name=ACS_2008_1YR_G00_.

- ^ "The Portland Streetcar Loop Project". portlandstreetcar.org. http://www.portlandstreetcar.org/node/11. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ "Portland-Milwaukie Light Rail Bridge to bring new options for transit, cyclists and pedestrians". trimet.org. http://www.trimet.org/pdfs/pm/Fact-sheets-timelines/PMLR-Bridge-Fact-Sheet-August2011.pdf. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ "Trimet website". Mytrimet.com. http://www.myTrimet.com. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ "League of American Bicyclists * Press Releases". Bikeleague.org. http://www.bikeleague.org/media/press/. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ "11 Most Bike Friendly Cities in the World – Bicycle friendly cities". Virgin Vacations. Virgin Airlines. http://www.virgin-vacations.com/11-most-bike-friendly-cities.aspx. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ Bicycle Commute Challenge information

- ^ 'Youth Magnet' Cities Hit Midlife Crisis The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved on June 14, 2009.

- ^ "19: Portland's Skatepark Master Plan". Skaters for Portland Skateparks. http://skateportland.org/?page_id=11. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ Dougherty, Conor (July 30, 2009). "Skateboarding Capital of the World". The Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204119704574238073660408040.html. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ^ Mary Judetz, "Portland: Largest U.S. city with openly gay mayor" (January 2, 2009). Associated Press

- ^ "Oregon Measure 36 Results by County". Uselectionatlas.org. http://www.uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?year=2004&off=60&elect=0&fips=41&f=0. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ "FBI's Joint Terrorism Task Force". ACLU Oregon. April 28, 2005. http://www.aclu-or.org/content/fbis-joint-terrorism-task-force.

- ^ Byron York (November 28, 2010). "Politically correct Portland rejected feds who saved city from terrorist attack". Washington Examiner. http://washingtonexaminer.com/blogs/beltway-confidential/2010/11/politically-correct-portland-rejected-feds-who-saved-city-terrori.

- ^ "How Houston gets along without zoning – BusinessWeek". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. http://www.businessweek.com/the_thread/hotproperty/archives/2007/10/how_houston_get.html. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Sherry Thomas, special for USATODAY.com (Posted October 30, 2003 12:20 pm). "Houston: A city without zoning". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/travel/destinations/cityguides/houston/2003-10-07-spotlight-zoning_x.htm. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Author: Michael Lewyn. "Zoning Without Zoning | Planetizen". Planetizen.com. http://www.planetizen.com/node/109. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Robert Reinhold (Published: August 17, 1986). "FOCUS: Houston; A Fresh Approach To Zoning – New York Times". Query.nytimes.com. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A0DEFDB103FF934A2575BC0A960948260. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Schadewald, Bill (April 9, 2006). "'The only major U.S. city without zoning' – Houston Business Journal:". Houston.bizjournals.com. http://houston.bizjournals.com/houston/stories/2006/04/10/editorial1.html. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Statewide Planning Goals. Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Comprehensive Land Use Planning Coordination". Legislative Counsel Committee of the Oregon Legislative Assembly. http://www.leg.state.or.us/ors/197.html. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ Law, Steve (October 28, 2009). "Council adopts aggressive Climate Action Plan". The Portland Tribune. http://www.portlandtribune.com/news/story.php?story_id=125678469206117000. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "Grist 15 Green Cities". Grist Magazine Online. http://www.grist.org/news/maindish/2007/07/19/cities/index.html. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- ^ Sienstra (March 24, 2010). "Top 10 greenest cities: Portland makes the cut". The Oregonian. http://www.oregonlive.com/idahosportugal/index.ssf/2010/03/portland_makes_list_of_top_10.html. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Kipen, Nicki (March 24, 2010). "The Top 10 Greenest Cities". Move.com. http://www.move.com/home-finance/real-estate/general/top-greenest-cities-in-us.aspx. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Busse, Phil (November 7, 2002). "Cover Yourself!". The Portland Mercury. http://www.portlandmercury.com/portland/Content?oid=27886&category=22101. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Moore, Adam S.; Beck, Byron (November 8, 2004). "Bump and Grind". Willamette Week. http://www.wweek.com/story.php?story=6093. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Susan Donaldson James (October 22, 2008). "Strip Club Teases Small Oregon City—In National Capital of Stripping, Residents Say Free Speech Has Gone Too Far". ABC News. http://abcnews.go.com/TheLaw/Story?id=6088041&page=1. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ "Judge: Salem lap dances protected by constitution". KATU News. Associated Press. June 30, 2007. http://www.katu.com/news/local/8263157.html. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ "Is Portland 'Pornland?' Nightline highlights city sex trade". September 23, 2010. http://www.katu.com/news/103648264.html. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Rather, Dan (May 18, 2010). "Dan Rather: Pornland, Oregon: Child Prostitution in Portland". The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dan-rather/pornland-oregon-child-pro_b_580035.html. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Palahniuk, Chuck (2003). Fugitives & refugees: a walk in Portland, Oregon. New York: Crown Journeys. p. 101. ISBN 1-4000-4783-8.

- ^ "Judge: riding in the buff is 'tradition,' man cleared". Associated Press. KATU. November 21, 2008. http://www.katu.com/news/local/34445764.html. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ magnifiquem (June 12, 2009). "BUTTCRACKS AND BICYCLES: the Portland naked bike ride 2009!". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5wSKi5Bchk. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- ^ "Cyclists bare all in naked ride through Portland". KATU. June 14, 2009. http://www.katu.com/news/local/48028862.html. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- ^ Jonathan Maus, BikePortland (June 15, 2009). "Portland Naked Bike Ride: 5000 People". PDX Pipeline. http://pdxpipeline.wordpress.com/2009/06/15/portland-naked-bike-ride-5000-people-pictures-story/. Retrieved June 22, 2009.