- Hurricane Andrew

-

This article is about the 1992 hurricane. For the 1986 tropical storm, see Tropical Storm Andrew (1986).

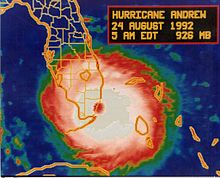

Hurricane Andrew Category 5 Hurricane (SSHS)

Hurricane Andrew approaching the Bahamas and Florida as a Category 5 hurricane Formed August 16, 1992 Dissipated August 28, 1992 Highest winds 1-minute sustained:

175 mph (280 km/h)Lowest pressure 922 mbar (hPa; 27.23 inHg) Fatalities 26 direct, 39 indirect Damage $26.5 billion (1992 USD)

(Third costliest tropical cyclone in U.S. history)Areas affected Bahamas; South Florida, Louisiana, and other areas of the Southern United States Part of the 1992 Atlantic hurricane season Hurricane Andrew was the third Category 5 hurricane to make landfall in the United States, after the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 and Hurricane Camille in 1969. Andrew was the first named storm and only major hurricane of the otherwise inactive 1992 Atlantic hurricane season. During Andrew's duration it struck the northwestern Bahamas, southern Florida at Homestead (south of Miami), and southwest Louisiana around Morgan City in August.[1] Andrew caused $26.5 billion in damage (1992 USD, $41.5 billion 2011 USD), with most of that damage cost in south Florida, which it struck at Category 5 strength; however, other sources estimated the total cost between $27 billion (1992 USD, $42.3 billion 2011 USD) and $34 billion (1992 USD, $47 billion 2011 USD). Its central pressure ranks as the fourth-lowest in U.S. landfall records. Andrew was the costliest Atlantic hurricane in U.S. history prior to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. It was also surpassed by Hurricane Ike in 2008.

Contents

Meteorological history

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa on August 14. Under the influence of a ridge of high pressure to its north, the wave tracked quickly westward, developing into Tropical Depression Three late on August 16 about 1,630 mi (2,620 km) east-southeast of Barbados. By August 17, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Andrew,[1] and by the following day had organized convection and estimated winds of 50 mph (80 km/h).[2] Shortly thereafter the thunderstorms decreased markedly,[3] and as the storm turned to the northwest it encountered southwesterly wind shear from an upper-level low.[1] On August 19, a Hurricane Hunters flight into the storm failed to locate a well-defined center,[4] and the next day a flight found only a broad circulation with an unusually high pressure of 1,015 mb (30.0 inHg). Around that time, the upper-level low degenerated into a trough, which decreased the wind shear over the storm. In addition, a strong ridge developed over the southeastern United States, which built eastward and caused Andrew to turn to the west.[1]

The storm gradually re-intensified, and after developing an eye, Andrew attained hurricane status early on August 22 about 650 mi (1,050 km) east-southeast of Nassau, Bahamas. The hurricane accelerated as it tracked due westward into an area of very favorable conditions, and late on August 22 began rapidly intensifying; in a 24 hour period the pressure dropped 47 mb (1.4 inHg) to a minimum pressure of 922 mb (27.2 inHg).[1] On August 23 Andrew attained Category 5 status on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, and at 1800 UTC that day it reached peak winds of 175 mph (282 km/h) while located a short distance off Eleuthera island.[5] Operationally, the National Hurricane Center assessed its peak intensity as 150 mph (240 km/h),[6] although it was reanalyzed and re-classified as a Category 5 hurricane twelve years subsequent to the hurricane.[5] At its peak, Andrew was a small hurricane, with winds of 35 mph (56 km/h) extending out only 90 miles (140 km) from the center.[7] Subsequent to peaking in intensity, the hurricane underwent an eyewall replacement cycle,[8] and at 2100 UTC on August 23, Hurricane Andrew struck Eleuthera with winds of 160 mph (260 km/h).[5] The hurricane weakened further while crossing the Bahama Banks, and at 0100 UTC on August 24 Andrew hit the southern Berry Islands of the Bahamas with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h).[5]

As it crossed over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream in the Straits of Florida, the hurricane rapidly re-intensified as the eye decreased in size and its eyewall convection deepened.[1] At 0840 UTC on August 24, Andrew struck Elliott Key with winds of 165 mph (266 km/h) and a pressure of 926 millibars (27.3 inHg). About 25 minutes later the hurricane hit the Florida mainland about 9 mi (15 km) northeast Homestead, or 20 mi (33 km) south-southwest of Miami, with the same winds and a minimum pressure of 922 mb (27.2 inHg).[5] While crossing southern Florida, the hurricane weakened slightly and emerged into the Gulf of Mexico with winds of 135 mph (217 km/h).[1] The eye remained well-defined as it turned to the west-northwest,[9] and Andrew reached winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) by late on August 25.[5]

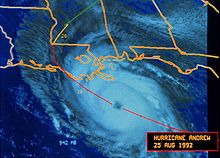

As the high pressure system to its north weakened, a strong approaching cold front caused the hurricane to decelerate to the northwest.[1] The winds decreased while the hurricane neared the Gulf Coast of the United States, and at 0830 UTC on August 26 Andrew made its final landfall in a sparsely populated area of Louisiana about 20 mi (32 km) west-southwest of Morgan City with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h).[5] It deteriorated rapidly as it turned to the north and northeast, and within ten hours weakened to a tropical storm. After entering Mississippi, the cyclone weakened to tropical depression status early on August 27. Accelerating northeastward, the tropical depression began merging with the approaching frontal system, and by midday on August 28 Andrew ceased to meet the qualifications of a tropical cyclone while located over the southern Appalachian Mountains.[1] The remnants continued to the northeast and lost its identity within the frontal zone over the Mid-Atlantic states.[10]

Statistics

Most intense landfalling U.S. hurricanes

Intensity is measured solely by central pressureRank Hurricane Season Landfall pressure 1 "Labor Day" 1935 892 mbar (hPa) 2 Camille 1969 909 mbar (hPa) 3 Katrina 2005 920 mbar (hPa) 4 Andrew 1992 922 mbar (hPa) 5 "Indianola" 1886 925 mbar (hPa) 6 "Florida Keys" 1919 927 mbar (hPa) 7 "Okeechobee" 1928 929 mbar (hPa) 8 Donna 1960 930 mbar (hPa) 9 Carla 1961 931 mbar (hPa) 10 Hugo 1989 934 mbar (hPa) Source: National Hurricane Center Reports from private barometers helped establish that Andrew's central pressure, at landfall near Homestead, Florida, was 922 mb (27.2 inHg).[1] At the time, this was the third-lowest pressure on record for a landfalling hurricane in the United States (it is now fourth, after 2005's Hurricane Katrina).[11]

Andrew's peak winds in South Florida were not directly measured, primarily because of the destruction or failure of measuring instruments. The Coastal Marine Automated Network (C-MAN) station at Fowey Rocks, with platform elevation of 141 feet (43 m), in its last transmission at 4:30 a.m. EDT, August 24, recorded an 8-minute average wind of 142 mph (229 km/h) with a peak gust of 169 mph (272 km/h) shortly before the equipment was destroyed. It is probable that higher winds occurred at Fowey Rocks after the station was destroyed.[1]

Another important wind speed report came from the Kendall-Tamiami Executive Airport, located nine miles (14 km) west of the shoreline. While weather observations had been suspended at the station, the official weather observer there stayed on duty and continued to make wind speed readings. At 4:45 a.m. EDT, August 24, he noted that the wind speed indicator was "pegged" at a position a little beyond the instrument's highest value of 120 mph (195 km/h), at a point he estimated to be around 10 mph (200 km/h). The needle reportedly remained "fixed" at this location for 3–5 minutes before dropping to "0" when the anemometer failed. These observations were closely corroborated by two other observers. He also indicated that the weather conditions continued to worsen for an additional 30 minutes after the anemometer failed. It is probable that much stronger winds occurred at this location.[1]

The highest recorded surface gust, within Andrew's northern eyewall, occurred at the home of a resident about a mile from the shoreline in Perrine, Florida. During the peak of the storm, a gust of 212 miles per hour (341 km/h) was observed before both the home and anemometer were destroyed. Subsequent wind-tunnel testing at Clemson University of the same type of anemometer revealed a 16.5% error. The observed value was officially corrected to be 177 mph (285 km/h).[1]

Data collected at the Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station terminated at 5:05 EDT before winds reached maximum strength. The anemometer recorded sustained winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) before it failed, and a barometric pressure of 922 mb (27.2 inHg) was recorded. Gusts exceeding 175 mph (280 km/h) were also observed. The data from Turkey Point reflects shoreline measurements (not inland), as it is situated directly on the coastline.[12] A National Weather Service-Miami Radar image recorded on 24 August 1992 at 4:35 EDT [08:35 UTC] superimposed on a street map by the Hurricane Research Division of NOAA indicates the most powerful winds within the northern eyewall (conditions greater than 48 dBZ) made landfall between SW 152 Street (Coral Reef Drive) and SW 184 Street (Eureka Drive) in the Perrine/Cutler Ridge area.[12] dBZ readings indicate Decibels of Z (radar echo intensity/reflectivity) and help map the relative strength of storm activity within a weather system. This extremely powerful band within the northern eyewall corresponds with the exact latitude range where the highest surface wind gusts of 177 mph (248.8 km/h) and lowest barometric pressure was recorded at a private home in Perrine and evaluated by Clemson University.[1] This corridor is also in line with the former Burger King corporate headquarters, located on the shoreline at the terminus of 184th Street (Eureka Drive), where one of the highest storm surge levels was recorded (16.9 ft).[12]

In 2002, The Atlantic Basin Hurricane Database Reanalysis Project examined Hurricane Andrew and this corridor of extreme winds embedded within Andrew's northern eyewall. The project concluded that Category 5 conditions on land occurred only in a small region of southern Dade (now Miami-Dade) County, specifically close to the coast in Cutler Ridge. The remaining areas affected by Andrew's initial landfall in Florida likely experienced sustained Category 4 and 3 hurricane conditions. Andrew was officially re-classified as a Category 5 storm in 2004, and the reanalysis provides a more comprehensive and detailed examination of Andrew's wind field structure upon landfall than originally assessed in 1992.[5]

The National Hurricane Center, then located along U.S. 1 in Coral Gables, recorded a peak gust of 164 mph (264 km/h) measured 130 feet (40 m) above the ground, just before 5 a.m. EDT. The anemometer was severely damaged at 5:17 a.m. EDT and by 5:45 a.m. had been completely destroyed.[1]

High winds occurred in other locations across Southern Florida, including peak gusts of 115 mph (185 km/h) estimated at Miami International Airport and 132 mph (212 km/h) recorded at Haulover Beach, Florida.[1]

In 2002, as part of an ongoing review of historical hurricane records, National Hurricane Center experts concluded that Andrew had sustained winds of 165 mph (266 km/h) briefly before and during landfall, making it a Category 5.[1]

Berwick, Louisiana reported sustained winds of 96 mph (154 km/h) with gusts to 120 mph (190 km/h). The highest gust of 175 mph (282 km/h) was reported from a drilling barge on Bayou Teche in coastal St. Mary Parish, Louisiana.[13]

Preparations

Bahamas

Main article: Effects of Hurricane Andrew in The BahamasBefore the hurricane passed through the Bahamas, forecasters predicted a storm surge of up to 18 ft (5.5 m), as well as up to 8 in (200 mm) of rain.[14] On August 22, hurricane watches were issued from Andros and Eleuthera islands, northward through Grand Bahama and Great Abaco. They were upgraded to hurricane warnings later that day, and on August 23 additional warnings were issued for the central Bahamas, including Cat Island, Exuma, San Salvador Island, and Long Island. All watches and warnings were discontinued on August 24.[1] Advanced warning was credited for the low death toll in the country.[15]

United States

Florida

By 11 PM Eastern Daylight Time, residents were warned that precautions to protect life and property should have been completed. About 55,000 people left the Florida Keys. Evacuations were ordered for 517,000 people in Dade County, 300,000 in Broward County, 315,000 in Palm Beach County and 15,000 in St. Lucie County. For counties further west in Florida, evacuation totals exceeding one thousand people are Collier (25,000), Glades (4,000) and Lee (2,500).[1] A 7 to 10-foot (3.0 m) storm surge was predicted for Eastern Florida and the Florida Keys, and a 7 to 11-foot (3.4 m) storm surge was predicted for Western Florida before the storm exited Florida. Some isolated tornadoes were also predicted for South and Central Florida for August 23 and August 24.[16] At least 8,000 Florida National Guard troops were deployed to prevent looting.[17][18] Another 27,000 active duty military were deployed. Many hurricane watches and warnings were issued in Florida because of Hurricane Andrew, including a hurricane warning issued on August 23 that stretched from Vero Beach all the way to the Florida Keys and to Dry Tortugas. All watches and warning in the state were discontinued late on August 24 after Andrew moved offshore of Florida.[1]

Louisiana

Sandbag walls were created in the South Bell Telephone Building in New Orleans. Sandbag walls were also created in the French Quarter section of New Orleans. Floodgates were also closed throughout the New Orleans Levee system. Sandbags for the public ran out because of the protection of major areas. Flights headed to and from New Orleans were canceled.[19] There were many watches and warnings issued because of Andrew. For about two days the entire southern coast of Louisiana was covered in warning and watches. All hurricane watches and warnings were discontinued after Andrew made landfall near Morgan City, Louisiana.[1]

Elsewhere

As Andrew approached the Gulf Coast, tropical storm/hurricane watches and warnings were also issued in Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas. All watches and warnings were discontinued on August 25 after Andrew had moved inland over Louisiana. In addition, 250,000 people evacuated Orange and Jefferson Counties in Texas.[1]

Impact

Bahamas

In the Bahamas, Andrew produced hurricane force winds in North Eleuthera, New Providence, North Andros, Bimini, Berry Islands.[20] It first struck Eleuthera,[21] where it produced a high storm surge that was described as a "mighty wall of water".[15] One person drowned from the surge in Eleuthera, and two others died in nearby The Bluff.[22] The hurricane also produced several tornadoes in the area.[23] Further west, Andrew spared damage to the capital city of Nassau,[24] but on the private island of Cat Cay, many wealthy homes sustained heavy damage.[25] Much of the northwestern Bahamas received damage,[23] with monetary damage estimated at $250 million (1992 USD, $391 million 2011 USD).[1] A total of 800 houses were destroyed, leaving 1,700 people homeless. Additionally, the storm left severe damage to the sectors of transport, communications, water, sanitation, agriculture, and fishing.[24] The hurricane caused four deaths in the country, of which three directly;[1] the indirect fatality was due to a heart failure during the passage of the storm.[22]

Florida

As with most high-intensity storms (Categories 4 and 5), the worst damage from Andrew is thought to have occurred not from straight-line winds but from vortices, or "miniwhirls" (something like embedded tornadoes). This was the conclusion of Tetsuya Theodore Fujita, a University of Chicago meteorologist who is known for the development of the Fujita scale for measuring the strength of tornadoes.

Andrew produced a 17 feet (5.2 m) storm surge near the landfall point in Florida. A tidal surge of 16.9 feet (5.2 m) was recorded at the shoreline of SW 184th Street (Eureka Drive), the former location of the Burger King world corporate headquarters on the coast of the Perrine/Cutler Ridge area (directly within the path of the northern eyewall).[12] Storm surge destruction was minimal, though, because of Andrew not moving over Miami itself.

Rainfall was limited in Southeast Florida because of Andrew traveling through at fast speeds, ranging from 20 to 25 mph (32 to 40 km/h).

Unlike most hurricanes, the vast majority of the damage in Florida was due to the winds. The agricultural loss in Florida was $1.04 billion (1992 USD) alone.[26]

In Dade County 90% of homes had major roof damage. 117,000 were destroyed or had major damage.[26]

The Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station was hit directly by Andrew. Over $90 million of damage was done, largely to a water tank and to a smokestack of one of the fossil-fueled units on-site, but the containment buildings were undamaged. The nuclear plant was built to withstand winds of up to 235 mph (378 km/h).

Massive damage caused by Andrew at Homestead Air Force Base, very near the point of landfall on the South Florida coast, led to the closing of the base as a full active-duty base. It was later partly rebuilt and operates today as a U. S. Air Reserve base. The aircraft and squadron were relocated to Aviano Air Base in Italy.

Power lines to the Florida Keys were destroyed, leaving residents without power. However, water was maintained, although it had to be boiled.[27]

There was also moderate damage to the coral reef areas offshore of Florida down to depths of 75 feet (23 m).[26]

The effects of Hurricane Andrew on Florida wetlands were considerable. In the Florida Everglades, 25%, 70,000 acres (280 km2) of trees were knocked down by the storm. It took 20 days for new trees and vegetation to grow following the storms passing. Damage to marine life was moderate as the storm increased the turbidity and lowered the oxygen level in the water, threatening many fish and other marine wildlife. In addition, the storm killed 182 million fish in the basin, causing $160 million (1992 USD) in lost value.[28]

Louisiana

After hitting Florida, Andrew moved across the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall about 23 mi (37 km) west-southwest of Morgan City in south-central Louisiana; at landfall, the maximum sustained winds were 115 mph (185 km/h). As it moved ashore, the hurricane produced storm tides of at least 8 ft (2.4 m), causing flooding along the coast from Vermilion Bay to Lake Borgne.[1] River flooding was also reported, with the Tangipahoa River in Robert cresting at 3.8 ft (1.2 m) above flood stage.[29] Before making landfall, Andrew spawned an F3 tornado in Laplace, which stayed on the ground until Reserve, St. John the Baptist Parish. Two people were killed as a result of that tornado.[13][1] The tornado was on the ground for about 10 minutes, during which it damaged or destroyed 163 structures which left 60 families homeless.[29] Tornadoes were also reported in the parishes of Ascension, Iberville, Pointe Coupee, and Avoyelles, as well as in Baton Rouge.[1] Heavy rains accompanied the storm's passage through the state, peaking at 11.02 in (280 mm) in Robert.[1][30]

Due to high winds, about 152,000 electricity customers lost their power because of the impact of Andrew. The hurricane knocked down 80% of the trees in part of the Atchafalaya River Basin near the coast. In addition to tree damage, significant agricultural damage was also reported in Louisiana in the wake of Hurricane Andrew. Damage was done to soy bean, corn, and sugar cane crops. The damage estimated done to the sugar cane was $200 million (1992 USD).[31]

Offshore, the storm killed 9.4 million fish, causing $7.8 million (1992 USD, $12.2 million 2011 USD) in lost value, and damaged large areas of marshland along the Louisiana coast.[28] Also offshore, a group of six fishermen from Alabama perished due to drownings.[1][29][32] A Coast Guard helicopter had to rescue four people and two dogs from a disabled 65 ft (20 m) fishing boat, 50 mi (80 km) south of Houma.[19]

Damage was estimated at $1 billion (1992 USD, $1.57 billion 2011 USD). There were nine indirect deaths in the state,[1] one of which in Lafayette from a car accident due to a power outage affecting a traffic light.[33] In addition, there were eight direct fatalities as a result of Andrew.[1]

Remainder of United States

Offshore the gulf states, Hurricane Andrew left about $500 million in damage to oil facilities. One company lost 13 platforms, had 104 structures damaged, and five drilling wells blown off course.[1]

As Andrew moved ashore in Louisiana, its outer fringes produced a storm tide of about 1.3 ft (0.40 m) in Sabine Pass, Texas. Winds were minor in the state, reaching 30 mph (48 km/h) in Port Arthur.[1]

After moving through Louisiana, Tropical Storm Andrew crossed Mississippi, prompting 3 severe thunderstorm warnings, 21 tornado warnings, and 16 flood warnings. Funnel clouds were observed along its path,[34] and there were 26 tornadoes across the state.[35] Structural damage was generally minimal, occurring from the tornadoes and severe thunderstorms. The winds also knocked down trees in the southwestern portion of the state.[34] The storm also dropped rainfall across much of the state,[36] peaking at 9.30 in (236 mm) at Sumrall.[30] The rainfall caused flooding in low-lying areas and creeks, covering a few county roads but not entering many houses or businesses.[36] Along the coast, the storm produced flooding and high tides.[32]

In neighboring Alabama, the storm's rainfall peaked at 4.71 in (120 mm) in Aliceville.[30] Along Dauphin Island, high tides left severe beach erosion, with up to 30 ft (9.1 m) lost in some areas.[32] Two damaging tornadoes occurred in the state, and wind gusts of 41 mph (67 km/h) were reported in Huntsville.[1] Damage was generally minor in Alabama.[32] Tropical storm force wind gusts extended eastward into Georgia, where damaging tornadoes were also reported. Monetary damage in the state reached about $100,000 (1992 USD, $157 thousand 2011 USD).[1] Rainfall from Andrew spread across the southeastern United States along the Appalachian Mountains corridor. Totals of over 5 inches (125 mm) were reported near the tri-point border between Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. Rainfall continued along the path of Andrew's remnants through the Mid-Atlantic and Ohio Valley.[10]

Costliest U.S. Atlantic hurricanes

Cost refers to total estimated property damageRank Hurricane Season Damages 1 Katrina 2005 $108 billion 2 Ike 2008 $29.5 billion 3 Andrew 1992 $26.5 billion 4 Wilma 2005 $21 billion 5 Ivan 2004 $18.8 billion 6 Charley 2004 $15.1 billion 7 Rita 2005 $12 billion 8 Frances 2004 $9.51 billion 9 Allison 2001 $9 billion 10 Jeanne 2004 $7.66 billion Source: NOAA[37] Main article: List of costliest Atlantic hurricanes

Aftermath

Florida

The slow response of federal aid to storm victims in southern Florida led Dade County emergency management director Kate Hale to famously exclaim at a nationally televised news conference, "Where in the hell is the cavalry on this one? They keep saying we're going to get supplies. For God's sake, where are they?" Almost immediately, President George H. W. Bush promised, "Help is on the way," and mobile kitchens and tents, along with units from the 82nd Airborne Division and the 10th Mountain Division, Fort Drum, New York began pouring in.[38]

Insurance claims in the wake of the extreme damage caused by Andrew led to the bankruptcy and closure of 11 insurance companies and drained an excessive amount of equity from 30 more. An estimated $16 billion of the total losses (mainly structural) were insured. The Federal Insurance Administration estimated that flood damage from the hurricane would total $100 million and that the program would cover all expected claims.[39] Even though a state-managed catastrophe fund was implemented to provide protection for the industry and its consumers, insurance rates and deductibles drastically increased.[40] Nearly one million residences were no longer eligible for coverage by any insurance company. This led the Florida Legislature to create new entities, such as the Joint Underwriting Association, the Florida Windstorm Underwriting Association, and the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, in effort to restore adequate insurance capacity.

Looting occurred in Florida after the storm, with at least 100 people attempting to ransack the Cutler Ridge shopping mall south of Miami. However, the deployment of 600 National Guard troops in the region restored order.[17]

Andrew's catastrophic damage spawned many rumors, including claims that hundreds or even thousands of migrant farm workers in south Dade County (now Miami-Dade County) were killed and their deaths were not reported in official accounts. An investigation by the Miami Herald found no basis for such rumors. These rumors were probably based on the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane, when the deaths of migrant workers initially went uncounted, and were still debated at the time of Andrew.

Homeowners and officials criticized developers and contractors for inadequate building practices and poor building codes. An inquiry after the storm concluded that there were probably construction flaws in some buildings, and that the state of Florida did enact some strict building codes since 1986, but they were either overlooked or ignored.[41]

In the decade after the storm, Hurricane Andrew may have contributed to the massive and sudden housing boom in Broward County, Florida. Located just north of Miami-Dade County, residents who had lost their homes migrated to western sections of the county that was just starting to be developed. The result was record growth in places like Miramar, Pembroke Pines and Weston.[28]

In commemoration of tenth anniversary of Hurricane Andrew, Biscayne National Park dedicated a plaque in 2002. The plaque reads:[42]

On Monday, August 24, 1992, at 4:30 a.m., the eye wall of Hurricane Andrew passed over this point before striking Homestead and southern Miami-Dade County. Andrew was one of the most powerful hurricanes in U.S. history with wind gusts exceeding 175 mph and a local record storm tide of 16.9 feet. Fifteen people in South Florida were killed by the forces of the hurricane and at least 29 died in its aftermath; hundreds more were injured. The destruction left at least 160,000 people homeless. Tens-of-thousands of jobs were affected and economic recovery took more than five years. Losses in Florida were estimated at $25-30 billion making Andrew the costliest hurricane disaster in U.S history.

Louisiana

Following the affects of Hurricane Andrew in Louisiana, then-President of the United States George H. W. Bush declared portions of the state as a disaster area.[13] In Louisiana, about 6,200 people had to be housed in 36 separate shelters, according to the American Red Cross. The Salvation Army sent in 37 mobile food storage faculties that served 40,000 meals, to help those who could get little or no food. Federal aid, from the Pentagon, sent in four 750 kilowatt generators, 2,500 cots, and 30,000 MREs, or prepackaged meals, to Louisiana. About 1,279 National Guard were deployed to Louisiana, to do various duties, from cooking to patrolling.[31] Shortly after the storm, Sheriffs along the coast of Louisiana imposed a curfew from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. local time. Alcohol sales were also banned immediately after the storm.[19]

Retirement

Because of the exceptional and widespread damage in Florida and Louisiana, the name Andrew was retired in the spring of 1993 and will never again be used for an Atlantic hurricane.[43] The name was replaced by Alex for the 1998 season.[44]

See also

- Hurricane Andrew, South Florida and Louisiana, August 23–26, 1992, report on the event by the NOAA Disaster Survey Team

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Florida hurricanes

- List of retired Atlantic hurricane names

- Timeline of the 1992 Atlantic hurricane season

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Edward Rappaport (1993-12-10). "Hurricane Andrew Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/1992andrew.html. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- ^ Rappaport, Edward (1992). "Tropical Storm Andrew Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/tropdisc/nal0492.005. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ Gerrish, Harold (1992). "Tropical Storm Andrew Discussion Eight". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/tropdisc/nal0492.008. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (1992). "Tropical Storm Andrew Discussion Thirteen". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/tropdisc/nal0492.013. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landsea, Christopher et al. (2004). "A Re-Analysis of Hurricane Andrew's Intensity". American Meteorological Society. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/Landsea/landseabams2004.pdf. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (1992). "Hurricane Andrew Discussion Thirty". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/tropdisc/nal0492.030. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Landsea, Christopher (2004). "Aren't big tropical cyclones also intense tropical cyclones?". Hurricane Research Division. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/tcfaq/C3.html. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Rappaport, Edward; Gerrish, Harold; Pasch, Richard (1992). "Hurricane Andrew Discussion Thirty-One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/tropdisc/nal0492.031. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Avila, Lixion; Mayfield, Max (1992). "Hurricane Andrew Discussion Thirty-Five". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/tropdisc/nal0492.035. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ a b Roth, David (2007). "Rainfall Summary for Hurricane Andrew". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/andrew1992.html. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

- ^ Knabb, Richard D; Rhome, Jamie R.; Brown, Daniel P (December 20, 2005; updated August 10, 2006). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Katrina: 23–30 August 2005" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL122005_Katrina.pdf. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

- ^ a b c d National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1992). NOAA landfall map (Map). http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/gifs/1992ed_andr2.gif.

- ^ a b c Roth, David (2010-01-14). "Louisiana Hurricane History". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. p. 47. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/research/lahur.pdf. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Max Mayfield (1992). "Hurricane Andrew Public Advisory 30". National Hurricane center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/public/pal0492.030. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ a b Jonathan Freedland (1992-09-02). "Storm Ravaged Island in Bahamas". Washington Post. http://tech.mit.edu/V112/N36/bahamas.36w.html. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- ^ Rappaport/Gerrish/Pasch (1992). "Hurricane Andrew Advisory 31". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/public/pal0492.031. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ a b "(Newspaper Upload "at0824p3")". http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/news/ap0824p3.gif.

- ^ "(Newspaper Upload at0824p1". http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/news/at0824p1.gif.

- ^ a b c "(The Inteligencer Summary of Impact (The Inteligencer)". http://www.thehurricanearchive.com/Viewer.aspx?img=26525313&firstvisit=true¤tResult=1¤tPage=0.

- ^ Arthur Rolle (1992). "Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas (2)". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/bahamas2.gif. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ Edward Rappaport (2005-02-07). "Hurricane Andrew Report Addendum". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/1992andrew_add.html. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ a b Arthur Rolle (1992). "Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas (4)". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/bahamas4.gif. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ^ a b Arthur Rolle (1992). "Hurricane Andrew in the Bahamas (3)". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/bahamas3.gif. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ a b United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (1992). "Bahamas and U.S.A. - Hurricane Andrew Aug 1992 UN DHA Information Reports 1-3". ReliefWeb. http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/RWB.NSF/db900SID/ACOS-64D966?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2008-12-06.

- ^ Edwin McDowell (1992-09-27). "After the storms: Three reports; Bahamas". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE7D91E3CF934A1575AC0A964958260&sec=travel&spon=&pagewanted=print. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ^ a b c Williams, John; Duedall, Ivar; Doehring, Fred (1997). Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2417-X.

- ^ Swanson and Wilkinson. "Florida Keys Hurricanes of the Last Millennium". Keys Historeum. http://www.keyshistory.org/hurricanelist.html. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Lovelace and McPherson (1998). "Effects of Hurricane Andrew (1992) on Wetlands in Southern Florida and Louisiana". U.S. Geological Survey. http://water.usgs.gov/nwsum/WSP2425/andrew.html. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ a b c New Orleans, LA National Weather Service (1992-09-15). "Final Storm Report... Hurricane Andrew... Corrected (Page 2)" (GIF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/new02.gif. Retrieved 2011-04-04.

- ^ a b c David M. Roth (2010-11-22). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Gulf Coast". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/tcgulfcoast.html. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ a b "(The Inteligencer)". http://www.thehurricanearchive.com/Viewer.aspx?img=26418438&firstvisit=true¤tResult=4¤tPage=0.

- ^ a b c d Faulkner, Mobile Alabama National Weather Service (1992-08-28). "Post Storm Report...Hurricane Andrew" (GIF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/pshmob.gif. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

- ^ Lake Charles, LA National Weather Service (1992-09-04). "Final Storm Report... Hurricane Andrew" (GIF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/pshlch01.gif. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ a b Steve Rich, Jackson, MS Weather Service Forecast Office (1992-09-03). "Tropical Storm Andrew" (GIF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/jackson1.gif. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ Jackson, MS National Weather Service (2010-09-22). "A Look Back at Hurricane Rita". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/jan/?n=2005_09_24_25_hurr_rita_tor. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ a b Steve Rich, Jackson, MS Weather Service Forecast Office (1992-09-03). "Tropical Storm Andrew (page 2)" (GIF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/storm_wallets/atlantic/atl1992/andrew/preloc/jackson2.gif. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ "The deadliest, costliest and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts)". National Climatic Data Center, National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011-08-10. p. 47. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/nws-nhc-6.pdf. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- ^ Adair (2002). "10 years ago, her angry plea got hurricane aid moving". St. Petersburg Times. http://www.sptimes.com/2002/webspecials02/andrew/day3/story1.shtml. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Pear, R. Hurricane Andrew: Breakdown seen in U. S. storm aid. The New York Times. August 29, 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Hopper (2005). "An American History of Disaster and Response". National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4839530. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Sainz (2002). "Ten years after Hurricane Andrew, effects are still felt". St. Petersburg Times. http://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/weather/hurricane/sfl-1992-ap-mainstory,0,913282.story. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ "Biscayne National Park Plaque Commemorates 10th Anniversary of Hurricane Andrew". National Weather Service. 2002. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/mfl/?n=hurricane_andrew_plaque_dedication. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ National Hurricane Center (2009). "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/retirednames.shtml. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- ^ ""Atlantic Storms 1996-2001"". National Hurricane Center. 1996. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/as.html. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

Further reading

- Sherrow, Victoria (1998). Hurricane Andrew: Nature's Rage. Enslow. ISBN 0766010570.

- Modified after the National Hurricane Center web site. This U.S. government site is in the public domain.

External links

Retired Atlantic hurricane names 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s Igor • TomasCategory 5 Atlantic hurricanes Pre-1950s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s Andrew • Mitch2000s Categories:- Hurricane Andrew

- 1992 Atlantic hurricane season

- Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- Retired Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricanes in the Bahamas

- Hurricanes in Florida

- Hurricanes in Louisiana

- 1992 meteorology

- 1992 in the United States

- History of the United States (1991–present)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.