- Curse of Ham

-

The Curse of Ham is a possible misnomer,[1] for the Curse of Canaan. The curse refers to Noah cursing Ham's offspring Canaan, for Ham's own transgression against his father, according to Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. The debate regarding upon whom the curse fell has raged for at least two thousand years, as early as Classical antiquity. Most commentators agree with the literal text of Genesis that it was Canaan who was cursed for the sin of his father, Ham. Interpretation remains divided as to whether or not Ham himself was actually cursed,[2] having himself committed the offense, which is only vaguely specified.

The narrative of Ham's transgression giving rise to the curse, can be found in Genesis 9:20-27, as well as in the Book of Jubilees 7:6-12. A brief retelling of the narrative was also discovered in the Dead Sea Scroll, Qumran 4Q252, Fragment I, Column II, Lines 6-8 [Gen.9:24-27].

In Psychological biblical criticism, there are psychoanalytic experts, in literary theory, who question the account, by proposing that it was Noah who sinned against Ham, while under the influence, then cursed his son as a means of using a reversal defense mechanism.[3] Others postulate that Ham had incestuous relations with his mother, Noah's wife.[4]

Racial interpretations of the curse of Ham have been used to promote racist religious ideologies, typically based in Abrahamic religions, to justify the enslavement of Black Africans.[5][6][7]

The story of Ham's transgression against his father Noah also parallels ancient Mesopotamian, Greek,[8] and Hittite myths.[9]

Contents

Cursed be narratives

Genesis narrative

Genesis 9:20 And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard:

21 And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent.

22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without.

23 And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness.

24 ¶ And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him.

25 And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.

26 And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

27 God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

(--Authorized Version)Jubilees narrative

Jubilees 7:6 And he rejoiced and drank of this wine, he and his children with joy.

7 And it was evening, and he went into his tent, and being drunken he lay down and slept, and was uncovered in his tent as he slept.

8 And Ham saw Noah his father naked, and went forth and told his two brethren without.

9 And Shem took his garment and arose, he and Japheth, and they placed the garment on their shoulders and went backward and covered the shame of their father, and their faces were backward.

10 And Noah awoke from his sleep and knew all that his younger son had done unto him, and he cursed his son and said: 'Cursed be Canaan; an enslaved servant shall he be unto his brethren.'

11 And he blessed Shem, and said: 'Blessed be the YHWH ALMIGHTY of Shem, and Canaan shall be his servant.

12 YHWH shall enlarge Japheth, and YHWH shall dwell in the dwelling of Shem, and Canaan shall be his servant.'

(--www.yahwehsword.org)4Q252 narrative

Fragment I, Column II:

Line 6: viii, 18 on the first day of the week. On that day Noah went forth from the ark

Line 7: ix, 24-5 at the end of a full year of three hundred and sixty-four days, on the first day of the week, on the seventeenth of the second month ~ on and six ~ Noah from the ark at the appointed time of a full year ~ And Noah awoke from his wine and knew what his youngest son had done to him. And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a slave of slaves shall he be to [his] bro[thers].

Line 8: ix, 27 But he did not curse Ham but only his son, for God had blessed the sons of Noah. And let him dwell in the tents of Shem.

(--Translated by Géza Vermès [10] )Curse origin interpretations

Ham not cursed

Jewish tradition holds that Ham was not cursed, since he was already blessed by God based on Genesis 9:1 as explained in Midrash Tanhuma, Genesis 16.[11] In Midrash Rabbah Genesis 36:7, R. Judah of the second century CE, explains, “there cannot be a curse where a blessing has been given.”

Justin Martyr, who is considered to be the first Christian writer to comment on Noah’s curse and blessings in Gen 9:25-27,[12] also supports the same view as rabbinic tradition, that Ham could not have been cursed as based on Genesis 9:1.[13] However, Martyr interpreted that the curse was transmitted onto all of Ham’s descendants, Canaan being as a representing example of a sorts.[14]

According to Josephus, Noah did not curse Ham himself, “because of his nearness of kin, but his posterity.” Divine vengeance only pursued the children of Chanan, whereas his brothers, Ham’s other children, escaped the curse.[15]

The Pesher on Genesis (4Q252) identifies the curse originating with Canaan. The brief narrative makes it very clear that Ham was not cursed, for “God had blessed the sons of Noah.”[Gen.9:1][16][17]

David M. Goldenberg, a scholar in Jewish religion and thought, and author of “The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam”,[18] postulates that it was not Ham whom Noah cursed, that the curse was clearly directed at Canaan. Goldenberg rejects any claims that the curse affected Ham or any of his other children.[19]

Narrative comparisons

Genesis interpretations

In Biblical criticism, source critics who follow Julius Wellhausen typically categorize the story of Noah, from Genesis 9:20-27, as an ethnological tradition that emerges from the conflict between Israel and Canaan. Noah's curse against Ham, in Genesis 9:25, is a curse against his son's lineage, by saying, “Cursed be Canaan; A servant of servants He shall be to his brethren."NKJV By using the expression “servant of servants”, otherwise translated “slave of slaves”,NIV this grammatical construction emphasizes the extreme degree of servitude that Canaan will undergo in relation to his "brothers".[20] In the following passage, "of Shem... may Canaan be his servant,"[9:26] the narrarator is foreshadowing Israel’s conquest of the promised land.[21]

In contrast, according to Umberto Cassuto, Ham’s transgression is an allegory that represents the Canaanite people. The Canaanites were to suffer the curse not because of Ham’s sin, but because they acted like him by their own transgressions. The passage of Canaan serving Shem refers to the children of Canaan who served under Chedorlaomer, king of Elam,[Gen 14:4] son of Shem.[22]

Saadia and Ibn Janah construe the curse to mean “cursed be [the father of] Canaan”, where the curse falls directly upon Ham himself. However, some source critics, like Ibn Ezra, argue that in the “fuller story”, Canaan, son of Ham, was a participant in the offense against Noah.[23]

Scholars have also suggested that Ham may have made fun of his fathers’ condition, inviting others to look at the strange sight of his nakedness. Such mocking would principally be opposed to the concept of honoring one’s father and mother,[24] which later became a command.[Ex.10:12]

Davies and Rogerson have suggested that the author of the text has Noah aim his curse specifically at Canaan, son of Ham in order to provide justification for the later Israelites to drive out and enslave the Canaanites.[25] Furthermore, within the larger narrative of the flood story, this curse provides a warning that, though the earth may not ever be punished in such a grand scope, this does not preclude the punishment of humankind.[26]

Jubilees interpretations

In the Book of Jubilees, the seriousness of Ham's curse is compounded by the cultic significance of God's covenant to "never again bring a flood on the earth".[27] In response to this covenant, Noah builds a sacrificial altar “to atone for the land”.[Jub. 6:1-3] Noah’s practice and ceremonial functions parallel the festival of Shavuot as if it were a prototype to the celebration of the giving of the Torah.[27][28] His “priestly” functions also emulate being "first priest" in accordance with halakhah as taught in the Qumranic works.[29][30] By turning the drinking of the wine into a religious ceremony, Jubilees alleviates any misgivings that may be provoked by the episode of Noah’s drunkenness. Thus, Ham’s offense would constitute an act of disrespect not only to his father, but also to the festival ordinances.[31]

Qumran 4Q252 interpretations

The Pesher on Genesis (4Q252) prompts considerable interest because of the types of exegesis found in the text.[32] The systematic linking of events of Noah’s life and the flood, to specific days of the week and month, may be hints to Noah having a priestly role.[33]

In contrast with Jubilees, where Noah is linked to the first celebration of the covenant, 4Q252 makes no mention of that covenant. It also omits the planting of the vineyard. Additionly, it makes it very clear that Ham was not cursed, only his son Canaan, because Ham had already been blessed by God in Genesis 9:1. This concept is also supported in the Tanhuma, Genesis 16.[11]

In an effort to find some thematic coherence, it has been suggested that such unity could include the elected and rejected [34] as well as contrasting traditions in which sin connected with sex is punished with destruction, but the righteous are rewarded with the possession of the land.[35] Noah’s disembarking from the ark and subsequent cursing of Canaan is the archetypical act, of the narrative, that makes distinctions between who would and who would not possess the land.[36]

Comparisons in mythology

According to the text published in 1498 by the monk Annio da Viterbo purporting to be an ancient Babylonian chronicle ("Pseudo-Berossus"), Ham studied the evil arts that had been practiced before the flood, and thus became known as "Cam Esenus" (Ham the licentious) as well as the original Zoroaster and Saturn (Cronus). He became jealous of Noah's additional children born after the deluge, and began to view his father with enmity. One day when Noah lay drunk and naked in his tent, Ham saw him and sang a mocking incantation that rendered Noah temporarily sterile, as if castrated. This account contains several other parallels connecting Ham with Greek myths of the castration of Uranus by Cronus, as well as Italian legends of Saturn and/or Camesis ruling over the Golden Age and fighting the Titanomachy. Ham in this account also abandons his wife who had been aboard the ark and had mothered the African peoples, and instead marries his sister Rhea, daughter of Noah, producing a race of giants in Sicily. Viterbo's text, while finding scholarly acceptance in the 16th century, has been widely dismissed as a forgery since ca. 1600.

Modern day authors such as J. M. Robertson, the novelist Robert Graves, and historian Raphael Patai, support the concept that the curse of Ham is related to the Greek myth of the castration of Uranus by Cronus [8][9] Graves and Patai also propose a connection with a Hittite myth of the supreme god Anu whose genitals were "bitten off by his rebel son and cup-bearer Kumarbi, who afterwards rejoiced and laughed (as Ham is said to have done) until Anu cursed him".[37]

Incest interpretations

Rabbinic sources are divided on the passage of Genesis 9:22-24 as to what actually happened in Noah's tent between him and his son, Ham. Rav maintains that Ham castrated his father. Rabbi Samuel claims that Ham sexually abused his father.[38] The former interpretation could explain why Noah did not have children after the flood.[39] W. G. Cole supports a sexual attack interpretation based on the text: “what his younger son had done to him”[Gen. 9:24][40] E. A. Speiser agrees that the phrase “saw his father’s nakedness” relates to genital exposure. However, he does not believe that it implies to a sexual offense as based on Genesis 42:9, 12; Genesis 2:25, and Exodus 20:26.[41]

Ham with Noah

In the field of Psychological biblical criticism, J. H. Ellens and W. G. Rollins use psychoanalytic literary theory to interpret incestuous relations that may have occurred between Ham and his father. They pose three psychoanalytical questions:[42]

- 1. Did Noah intentionally “uncover himself within his tent” and then lie down, or did he accidentally expose himself while sleeping?

- 2. If Noah intentionally removed his own clothing, was he sober enough to do so? Or, was he so intoxicated that he “became uncovered in his tent”?NKJV

- 3. At what point did Ham enter the tent? Was he already in the tent when Noah arrived or did he wander in sometime later?

Ellens and Rollins offer these three possible explanations:[43]

- 1. Noah was already undressed when Ham arrived; and it was Noah who initiated an incestuous liaison with his son.

- 2. Noah disrobed in his son’s presence surfacing a repressed incestuous homosexual fantasy that was not acted upon.

- 3. Upon seeing his father naked, Ham initiated a sexual encounter (as most commentators suggest).

In their view, it seems unlikely that Ham would run out looking for his brothers,[9:22] if he was the one that initiated a forbidden act. Ellens and Rollins support the view that perhaps Noah was the one who was really at fault, after having been intoxicated with wine. They point out that clinicians report that in most cases, children who have incestuous homosexual relations do not report the incident until many years later.[43][44] In light of the curse on Ham, psychologist Karen Horney states that a shamed person often needs to take revenge when humiliated, in order to save face. The shamed person feels triumphant by “shaming the shamer.” [45] Based on this psychoanalytical analysis, Ellen and Rollins conclude that if Noah was at fault, he probably felt shame and guilt when Ham’s brothers arrived to assess what happened. From this standpoint, when the brothers arrived, Noah cursed Ham as a way to reverse the situation.[43]

Ham with his mother

F. W. Bassett proposes that the idiomatic expression "saw his father’s nakedness" could mean that Ham had sexual intercourse with his mother, Noah's wife which resulted in the birth of Canaan and that is why he (Canaan) was cursed.[4] By this interpretation, Canaan is not cursed arbitrarily or capriciously but by the incest itself. Some in the modern creationism movement also share this view.[46] Biblical support for this interpretation is claimed to be from Leviticus 18, 20:11, 20-21, Ezekiel 22:10, and Habbakkuk 2:15. In particular the laws concerning forbidden sexual relationships in Leviticus 18 and 20 can be seen as supporting this interpretation. These laws consistently use the phrase "you shall not uncover the nakedness of..." when speaking about forbidden incest. This is of course the same phrase that is used in the narrative of the Curse of Ham. Moreover, when the Levitical laws employ this term it is always concerned with forbidden heterosexual sex, never homosexual sex. As such, this interpretation must be applied to the wife of Noah, not Noah himself as other interpretations do.[47] In this regard, the story of the Curse of Ham is most similar to Leviticus 18:8.

There are problems with this perspective. The textus receptus assumes that Canaan was born before this entire episode (Genesis 9:18). It is fully possible that this is simply a gloss reminding the reader that Ham would become the father of Canaan, but it is a difficulty with this interpretation. Obviously, if the text assumes that Canaan was already born before the story happened, then the story cannot possibly be an explanation as to why Canaan was cursed.[47]

Furthermore, Noah becomes aware of Ham's sin immediately after he became sober. If that sin was the birth of Canaan then there is a nine month gap that is hard to account for. In other words, if the sin is only recognizable by the pregnancy and birth, then how does Noah immediately know of the sin when he becomes sober?[48]

Finally, another problem emerges. This interpretation cannot account for Shem and Japheth's actions. It is fairly clear from the story that the three brothers are actually covering their father (Genesis 9:22). But if the sin is the incestual relationship and the resulting birth, why do Shem and Japheth act this way?[49]

Race and slavery interpretations

Jewish views

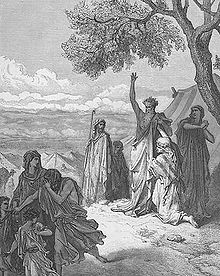

Noah curses Ham by Gustave Dore

Noah curses Ham by Gustave Dore

Although the story in Genesis is actually about Canaan, and although the Torah assigns no racial characteristics or rankings to Ham, early Jewish writers turned the focus of their attention from Canaan to Ham and interpreted the Biblical narrative in a racial way. The Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 108b states: "Our Rabbis taught: Three copulated in the ark, and they were all punished—the dog, the raven, and Ham. The dog was doomed to be tied, the raven expectorates [his seed into his mate's mouth], and Ham was smitten in his skin." {Talmud Bavli, Sanhedrin 108b} The nature of Ham's "smitten" skin is unexplained, but later commentaries described this as a darkening of skin. A later note to the text states that the "smitten" skin referred to the blackness of descendants, and a later comment by rabbis in the Bereshit Rabbah asserts that Ham himself emerged from the ark black-skinned.[50][51] The Zohar (a book central to Kabbalah) states that Ham's son Canaan "darkened the faces of mankind".[52] The episode of Moses marrying a Kushite woman has been construed by some as evidence against this interpretation of 'darkening.' When Aaron and his sister Miriam question this marriage God punishes Miriam with a skin disease that makes her skin 'like snow' [Num.12:10] (with the sense of 'flaky' rather than 'white').[53]

Rashi, the medieval Jewish commentator on Torah, explains the harshness of the curse: "Some say Cham saw his father naked and either sodomized or castrated him. His thought was "Perhaps my father's drunkenness will lead to intercourse with our mother and I will have to share the inheritance of the world with another brother! I will prevent this by taking his manhood from him! When Noah awoke, and he realized what Cham had done, he said, "Because you prevented me from having a fourth son, your fourth son, Canaan, shall forever be a slave to his brothers, who showed respect to me!"

Another notable medieval Jewish commentator on Torah, Abraham ibn Ezra, disagrees with Rashi: "And the meaning of '[Cursed be Canaan, he will be a slave] unto his brothers' is to Cush, Egypt, and Put [only], for they are his father's [other] sons. And there are those who say that the Cushim [black skinned people] are slaves because Noah cursed Ham [the father of Cush], but they forget that the first king after the flood [Nimrod] was a descendant of Cush, and so it is written, 'And the beginning of his kingdom was Babylonia.'"[Gen.10:10] I.e. since Nimrod was descended from Cush, and Nimrod was king, this proves the Cushites, i.e. black skinned people, cannot be under Canaan's curse of slavery.

Islamic views

Neither the Curse of Ham, nor the Curse of Canaan, are mentioned in the Qur'an.[54] Early Islamic scholars were aware of the story in the Torah and debated whether or not there was a curse on Ham's descendants, or instead on the descendants of Shem, and whether it even had any connection to their skin color.

In Islam, the support for the tradition that Noah cursed his son Ham, has been viewed as an utterance of a dual curse against him, by cursing him with blackness and slavery at the same time. The dual curse tradition is acknowledged in modern times as well as by Al-Kisā’ī, Ṭabarī (d. 923) and Tha'labī (d. 1036). It is also mentioned in the works of Akhbār al-zamān (10th or 11th Century), genealogists by Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), The Book of the Zanj, and the Book of the Gold Ingot (Sabā'ik adh-dhahab).[55]

- Al-Kisā’ī: " 'May God change your complexion and may your face turn black!' And that very instant his face did turn black... 'may He make bondswomen and slaves of Ham’s progeny until the Day of Resurrection!'" [56]

- Ṭabarī: “Ham begat all those who are black and curly-haired… Noah prayed that the hair of Ham’s descendants would not grow beyond their ears, and that wherever his descendants met the children of Shem, the latter would enslave them.” [57][58]

- Tha'labī: "He prayed that Ham’s color would be changed and that his descendants would be slaves to the children of Shem and Japheth."[59]

- Tha'labī quotes 'Atā': “Ham is the father of the Blacks (al-sudan)… 'Atā' said that Noah cursed Ham that the hair of his descendants should not grow below their ears, and wherever his offspring be, they wouold be slaves to the descendants of Shem and of Yafeth.”[60]

- Musa Kamara (d. 1945) quotes Tha'labī, about the dual curse, in Zuhur al-basatin.[61]

In Islam, the view that Race has nothing to do with Ham, are presented by author Al-Jahiz, an Afro-Arab and the grandson of a Zanj (Bantu)[62][63][64] slave, author of the book: Superiority Of The Blacks To The Whites. He offers his theory, contraire to the racial interpretations of the curse of Ham, as to why the Zanj were black in the "On the Zanj" chapter of The Essays.[65]

Ibn Khaldun also disputed this story, pointing out that the Torah makes no reference to the curse being related to skin colour and arguing that differences in human pigmentation are caused entirely by climate[66] and environmental determinism, and not because of any curse.[67] Ahmad Baba agreed with this view, rejecting any racial interpretation of the curse.

Commentators

- Origen (ca. 185-254): “For the Egyptians are prone to a degenerate life and quickly sink to every slavery of the vices. Look at the origin of the race and you will discover that their father Cham, who had laughed at his father’s nakedness, deserved a judgment of this kind, that his son Chanaan should be a servant to his brothers, in which case the condition of bondage would prove the wickedness of his conduct. Not without merit, therefore, does the discolored posterity imitate the ignobility of the race [Non ergo immerito ignobilitatem decolor posteritas imitatur].” - Homilies on Genesis 16.1.

- Mar Ephrem the Syrian (ca. 306 – 373): "When Noah awoke and was told what Canaan did. . .Noah said, ‘Cursed be Canaan and may God make his face black,’ and immediately the face of Canaan changed; so did of his father Ham, and their white faces became black and dark and their color changed.”[68]

- The Cave of Treasures, 4th century Syriac work, gives the explanation that Canaan's curse was actually earned because he revived the sinful music and arts of Cain's progeny that had been before the flood.[69] "And Canaan was cursed because he had dared to do this, and his seed became a servant of servants, that is to say, to the Egyptians, and the Cushites, and the Mûsâyê, [and the Indians, and all the Ethiopians, whose skins are black]."[70]

- Ishodad of Merv, the Syrian Christian bishop of Hedhatha, (9th century): When Noah cursed Canaan, “instantly, by the force of the curse. . .his face and entire body became black [ukmotha]. This is the black color which has persisted in his descendants.”[71]

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, a Persian historian (c. 915), recounted a version of the story where Noah cursed both Canaan and Ham to slavery, on account of Ham's action of seeing his father naked and not covering him.[72]

- Eutychius, an Alexandrian Melkite patriarch, (d. 940): “Cursed be Ham and may he be a servant to his brothers… He himself and his descendants, who are the Egyptians, the Negroes, the Ethiopians and (it is said) the Barbari.”[73]

- Ibn al-Tayyib, an Arabic Christian scholar, Baghdad, (d. 1043): “The curse of Noah affected the posterity of Canaan who were killed by Joshua son of Nun. At the moment of the curse, Canaan’s body became black and the blackness spread out among them.” [74]

- Bar Hebraeus, a Syrian Christian scholar, (1226–86): “‘And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father and showed [it] to his two brothers.’ That is…that Canaan was cursed and not Ham, and with the very curse he became black and the blackness was transmitted to his descendants… And he said, ‘Cursed be Canaan! A servant of servants shall he be to his brothers.’” [75][76]

- Anne Catherine Emmerich, a Catholic mystic (1774-1824): "I saw the curse pronounced by Noah upon Ham moving toward the latter like a black cloud and obscuring him. His skin lost its whiteness, he grew darker. His sin was the sin of sacrilege, the sin of one who would forcibly enter the Ark of the Covenant. I saw a most corrupt race descend from Ham and sink deeper and deeper in darkness. I see that the black, idolatrous, stupid nations are the descendants of Ham. Their color is due, not to the rays of the sun, but to the dark source whence those degraded races sprang".[77]

- John Brown, a Scottish Anglican Divine, published The Self-Interpreting Bible (1778). Genesis 9:25 footnote reads: “For about four thousand years past the bulk of Africans have been abandoned of Heaven to the most gross ignorance, rigid slavery, stupid idolatry, and savage barbarity.”[78]

Serfdom

The curse of Ham became used as a justification for serfdom during the medieval era. Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1100) was the first recorded to propose a caste system associating Ham with serfdom, writing that serfs were descended from Ham, nobles from Japheth, and free men from Shem. However, he also followed the earlier interpretation of 1 Corinthians 7:21 by Ambrosiaster (late 4th century), that as servants in the temporal world, these "Hamites" were likely to receive a far greater reward in the next world than would the Japhetic nobility.[79]

The idea that serfs were the descendants of Ham soon became widely promoted in Europe. At the height of the medieval era, it was a significant trend in Genesis exegesis to interpret that the descendants of Ham were serfs. Dame Juliana Berners (c. 1388) in a treatise on hawks, claimed that the "churlish" descendants of Ham had settled in Europe, those of Shem in Africa, and those of Japheth in Asia — a departure from normal arrangements — because she considered Europe to be the "country of churls", Asia of gentility, and Africa of temperance.[80] As serfdom waned in the late medieval era, the interpretation of serfs being descendants of Ham decreased as well.[81]

Proslavery

The curse of Ham has been used to promoted race and slavery movements as early as Classical antiquity. European biblical scholars of the Middle Ages supported the view that the "sons of Ham" or Hamites were cursed, possibly "blackened" by their sins.

Redemption of Ham illustrating the process of racial whitening (branqueamento) through miscegenation in Brazil

Redemption of Ham illustrating the process of racial whitening (branqueamento) through miscegenation in Brazil

Though early arguments to this effect were sporadic, they became increasingly common during the slave trade of the 18th and 19th centuries.[82] The justification of slavery itself through the sins of Ham was well suited to the ideological interests of the elite; with the emergence of the slave trade, its racialized version justified the exploitation of a ready supply of African labour.

In the parts of Africa where Christianity flourished in the early days, while it was still illegal in Rome, this idea never took hold, and its interpretation of scripture was never adopted by the African Coptic Churches. A modern Amharic commentary on Genesis notes the 19th century and earlier European theory that blacks were subject to whites as a result of the "curse of Ham", but calls this a false teaching unsupported by the text of the Bible, emphatically pointing out that this curse fell not upon all descendants of Ham but only on the descendants of Canaan, and asserting that it was fulfilled when Canaan was occupied by both Semites (Israel) and Japethites (ancient Philistines). The commentary further notes that Canaanites ceased to exist politically after the Third Punic War (149 BC), and that their current descendants are thus unknown and scattered among all peoples.[83]

Latter-day Saint movement

Main articles: Blacks and the Latter Day Saint movement and Blacks and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day SaintsAfter the death of Joseph Smith, Jr., Brigham Young, the church's second president, taught that Black Africans were under the curse of Ham, although the day would come when the curse would be nullified through the saving powers of Jesus Christ.[84] In addition, based on his interpretation of the Book of Abraham, Young believed that as a result of this curse Negroes were banned from the Mormon Priesthood,[85] but in 1978 Spencer W. Kimball claimed he received a revelation that extended the Priesthood to all worthy males.[86]

See also

- Curse and mark of Cain

- Ham (son of Noah)

- Hamitic

- Qumran 4Q252

- Sons of Noah

References

- ^ Alida C. Metcalf. Go-betweens and the colonization of Brazil, 1500-1600, (ISBN 0292712766, 9780292712768), 2005, p. 163-164

- ^ Goldenberg. The Curse of Ham, 2009, (ISBN 1400828546, 9781400828548), p. 157

- ^ Ellens & Rollins. Psychology and the Bible: From Freud to Kohut, 2004, (ISBN 027598348X, 9780275983482), p.51-59

- ^ a b Bassett, 1971, p.236

- ^ Cheesebrough, ed., “God Ordained This War.”

- ^ Daly, John Patrick When Slavery Was Called Freedom: Evangelicalism, Proslavery, and the Causes of the Civil War (Religion in the South The University Press of Kentucky (31 Oct 2004) ISBN 978-0813190938 p.37

- ^ Taslitz, Andrew E. Reconstructing the Fourth Amendment: a history of search and seizure, 1789-1868 New York University Press (15 Oct 2006) ISBN 978-0814782637 p.99

- ^ a b Robertson. Christianity and mythology, 1900, p.44

- ^ a b Graves & Patai. Hebrew Myths. The Book of Genesis, 1964

- ^ Géza Vermès. The complete Dead Sea scrolls in English, (ISBN 0140449523, 9780140449525), 4Q252, fr. I (Gen. vi, 3 – xv, 17)

- ^ a b T. A. Bergren. Biblical Figures Outside the Bible, 2002, (ISBN 1563384116, 9781563384110), p. 139, See notation # 77

- ^ Oskar Skarsaune. The proof from prophecy, (ISBN 9004074686, 9789004074682), 1987, p. 341

- ^ Shotwell. Exegesis, p. 96

- ^ Goldenberg. The Curse of Ham, 2009, (ISBN 1400828546, 9781400828548), p. 158

- ^ Josephus. “Genesis and the “Jewish Antiquities”, p. 112-13

- ^ 4Q252, Fragment I, Column II, Line 8

- ^ Goldenberg, 2009, p. 158

- ^ About D. M. Goldenberg (2009); Reviews at: Goldenberg's Curse of Ham reviews

- ^ Goldenberg, 2009, p. 157

- ^ Ellens & Rollins. 2004, p.54

- ^ Stephen R. Haynes. Noah's curse: the biblical justification of American slavery, 2002, (ISBN 0195142799, 9780195142792), p. 184

- ^ Williams. The Bible, Violence and the Sacred, 14-15

- ^ Sarna, 1989, p. 66

- ^ Herbert Wolf. “An Introduction to the Old Testament Pentateuch”, (ISBN 0802441564, 9780802441560), p. 127

- ^ The Old Testament World second edition. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. 2005. pp. 121–122. ISBN 0-664-23025-3.

- ^ The Old Testament World second edition. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. 2005. p. 122. ISBN 0-664-23025-3.

- ^ a b T. A. Bergren. Biblical Figures Outside the Bible, 2002, (ISBN 1563384116, 9781563384110), p. 137

- ^ Philo, Abr. 34

- ^ Albeck. Buch der Jubiäen,p. 21, 33

- ^ VanderKam. Righteousness of Noah,p. 20, 76

- ^ T. A. Bergren, 2002, p. 139

- ^ Fröhlich. Narrative Exegesis, p. 67-90

- ^ Moshe J. Bernstein, 4Q252: From Re-written Bible to Biblical Commentary, 1994

- ^ J. Saukkonen. From the Flood to the Messiah: Is 4Q252 a History Book?, 2004

- ^ Fröhlich. Narrative Exegesis, p. 87-88

- ^ Dorothy M. Peters. Noah traditions in the Dead Sea scrolls, (ISBN 1589833902, 9781589833906 ), 2008, p. 165

- ^ Graves & Patai, 1964, Ch.21, Note 4

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 70a

- ^ Ellens & Rollins, 2004, p.53

- ^ Cole, 1959, p.43

- ^ Speiser, 1964, p.61

- ^ Ellens & Rollins, 2004, p.55

- ^ a b c Ellens & Rollins, 2004, p.56

- ^ R. Medlicott, ‘Lot and his Daughters’, Australian New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 1 (1967), p. 135

- ^ K. Horney, 1950, p.103

- ^ Why Was Canaan Cursed? by Pastor Bob Enyart, Denver Bible Church

- ^ a b Hamilton, Victor P. (2005). Handbook on the Pentateuch Second Edition. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. p. 73. ISBN 0-8010-2716-0.

- ^ Hamilton, Victor P. (2005). Handbook on the Pentateuch Second Edition. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. pp. 73–74. ISBN 0-8010-2716-0.

- ^ Hamilton, Victor P. (2005). Handbook on the Pentateuch Second Edition. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. p. 74. ISBN 0-8010-2716-0.

- ^ Solors, Werner, Neither Black nor White Yet Both: Thematic Explorations of Interracial Literature, 1997, Oxford University Press, p. 87

- ^ The Midrash: The Bereshith or Genesis Rabba

- ^ Solors, p. 87

- ^ Goldenberg. The Curse of Ham, 2009, (ISBN 1400828546, 9781400828548), p. 27

- ^ "The Sons of Noah and the Construction of Ethnic and Geographical Identities in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods". Doctrine and Covenants (The William and Mary Quarterly). Vol. 54, No. 1 (Jan., 1997). JSTOR 2953314.

- ^ Goldenburg, 2009, p. 170

- ^ Kisā’ī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā' , Isaac Eisenberg, p. 99; Trans. Thackston, Tales of the Prophets, p. 105.

- ^ Ṭabarī, Tarikh. M. J. de Goeje, 1:223. Trans. Brinner. “The History of al-Tabari”, 2:21

- ^ Adang. Muslim Writers on Judaism, p. 39ff, 120ff

- ^ Tha'labī. Tarikh, 1:215; Trans. Brinner, The History of al-Tabari, 2:14

- ^ Tha'labī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā' , p. 61

- ^ Translated by Constance Hilliard. J.R.Willis. Slaves and Slavery in Muslim Africa, 1:165

- ^ F.R.C. Bagley et al., The Last Great Muslim Empires, (Brill: 1997), p.174

- ^ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.13

- ^ Bethwell A. Ogot, Zamani: A Survey of East African History, (East African Publishing House: 1974), p.104

- ^ "Medieval Sourcebook: Abû Ûthmân al-Jâhiz: From The Essays, c. 860 CE". Medieval Sourcebook. July 1998. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/860jahiz.html. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ^ Solors, Werner, Neither Black nor White Yet Both: Thematic Explorations of Interracial Literature, 1997, Oxford University Press, p. 90

- ^ El Hamel, Chouki (2002). "'Race', slavery and Islam in Maghribi Mediterranean thought: the question of the Haratin in Morocco". The Journal of North African Studies 7 (3): 29–52 [41–2].

- ^ Paul de Lagarde. Materialien zur Kritik und Geschichte des Pentateuchs,(Leipzig, 1867), part II

- ^ This sentiment also appears in the later Syriac Book of the Bee (1222).

- ^ Cave of Treasures, E. Wallis Budge translation from Syriac

- ^ C. Van Den Eynde, Corpus scriptorium Christianorum orientalium 156, Scriptores Syri 75 (Louvain, 1955), p. 139.

- ^ Tabari's Prophets and Patriarchs

- ^ Patrologiae cursus completes…series Graeca, ed. J.P. Migne (Paris, 1857–66), Pococke’s (1658–59) translation of the Annales, 111.917B (sec. 41-43)

- ^ Joannes C.J. Sanders, Commentaire sur la Genèse, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 274-275, Scriptores Arabici 24-25 (Louvain, 1967), 1:56 (text), 2:52-55 (translation).

- ^ Sprengling and Graham, Barhebraeus’ Scholia on the Old Testament, pp. 40–41, to Gen 9:22.

- ^ See also: Phillip Mayerson, “Anti-Black Sentiment in the Vitae Patrum”, Harvard Theological Review, vol. 71, 1978, pp. 304–311.

- ^ All-jesus.com

- ^ David M. Whitford . “The curse of Ham in the early modern era: the Bible and the justifications for slavery”, (ISBN 0754666255, 9780754666257), 2009, p. 171

- ^ Paul H. Freedman, 1999, Images of the mediaeval peasant p. 291; Whitford 2009 pp. 31-34.

- ^ Whitford 2009 p. 38.

- ^ David Mark Whitford (21 October 2009). The curse of Ham in the early modern era: the Bible and the justifications for slavery. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7546-6625-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=hMb7_SL-OJYC&pg=PA173. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Benjamin Braude, "The Sons of Noah and the Construction of Ethnic and Geographical Identities in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods, "William and Mary Quarterly LIV (January 1997): 103–142. See also William McKee Evans, "From the Land of Canaan to the Land of Guinea: The Strange Odyssey of the Sons of Ham,"American Historical Review 85 (February 1980): 15–43

- ^ ኦሪት ዘፍጥረት ት.መ.ማ. (Commentary on Genesis) p. 133-142.

- ^ Simonsen, Reed, If Ye Are Prepared, pp. 243-266.

- ^ Bush, Lester E. Jr; Armand L. Mauss, eds. (1984). Neither White Nor Black: Mormon Scholars Confront the Race Issue in a Universal Church. Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books. p. 70. ISBN 0-941214-22-2. http://www.signaturebookslibrary.org/neither/cover.htm.

- ^ "Official Declaration—2". Doctrine and Covenants. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 30 September 1978. http://scriptures.lds.org/od/2. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

External links

- Messenger and Advocate

- Sermon on separate heavens and race relations in Mississippi

- Jasher 7 An account of the theft of the garment by Ham is found in Jasher 7:24-29.

Categories:- Latter Day Saint doctrines, beliefs, and practices

- Historical definitions of race

- Racism

- Religion and race

- Slavery and religion

- Ham (son of Noah)

- Criticism of Judaism

- Book of Genesis

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.