- Massacre of the Latins

-

Massacre of the Latins

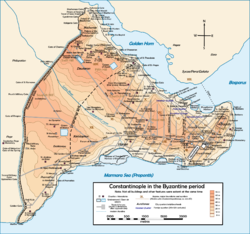

Map of Constantinople. The Latin quarters are captioned in purple.Location Constantinople, Byzantine Empire Date May 1182 Target Roman Catholics ("Latins") Attack type Massacre Death(s) Unknown, tens of thousands Perpetrator(s) Eastern Christian mob The Massacre of the Latins occurred in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, in May 1182.[1] It was a large-scale massacre of the Roman Catholic or "Latin" merchants and their families, who at that time dominated the city's maritime trade and financial sector. Although precise numbers are unavailable, the bulk of the Latin community, estimated at over 60,000 at the time,[2] was wiped out or forced to flee. The Genoese and Pisan communities especially were decimated, and some 4,000 survivors were sold as slaves to the Turks.[3]

The massacre further worsened relations and increased enmity between the Western and Eastern Christian and worlds,[4] and a sequence of hostilities between the two followed.

Contents

Background

Since the late 11th century, Western merchants, primarily from the Italian city-states of Venice, Genoa and Pisa, had started appearing in the East. The first had been the Venetians, who had secured large-scale trading concessions from Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Subsequent extensions of these privileges and Byzantium's own naval impotence at the time resulted in a virtual maritime monopoly and stranglehold over the Empire by the Venetians.[5] Alexios' grandson, Manuel I Komnenos, wishing to reduce their influence, began to reduce the privileges of Venice while concluding agreements with her rivals: Pisa, Genoa and Amalfi.[6] Gradually, all four Italian cities were also allowed to establish their own quarters in the northern part of Constantinople itself, towards the Golden Horn.

The predominance of the Italian merchants caused economic and social upheaval in Byzantium: it accelerated the decline of the independent native merchants in favour of big exporters, who became tied with the landed aristocracy, who in turn increasingly amassed large estates.[2] Together with the perceived arrogance of the Italians, it fueled popular resentment amongst the middle and lower classes both in the countryside and in the cities.[2] The religious differences between the two sides, who viewed each other as schismatics, further exacerbated the problem. The Italians proved uncontrollable by imperial authority: in 1162, for instance, the Pisans together with a few Venetians raided the Genoese quarter in Constantinople, causing much damage.[2] Emperor Manuel subsequently expelled most of the Genoese and Pisans from the city, thus giving the Venetians a free hand for several years.[7]

In early 1171, however, when the Venetians attacked and largely destroyed the Genoese quarter in Constantinople, the Emperor retaliated by ordering the mass arrest of all Venetians throughout the Empire and the confiscation of their property.[2] A subsequent Venetian expedition in the Aegean failed: a direct assault was impossible due to the strength of the Byzantine forces, and the Venetians agreed to negotiations, which the Emperor stalled intentionally. As talks dragged on through the winter, the Venetian fleet waited at Chios, until an outbreak of the plague forced them to withdraw.[8] The Venetians and the Empire remained at war, with the Venetians prudently avoiding direct confrontation but sponsoring Serb uprisings, besieging Ancona, Byzantium's last stronghold in Italy, and signing a treaty with the Norman Kingdom of Sicily.[9] Relations were only gradually normalized: there is evidence of a treaty in 1179,[10] although a full restoration of relations would only be reached in the mid-1180s.[11] Meanwhile, the Genoese and Pisans profited from the dispute with Venice, and by 1180, it is estimated that up to 60,000 Latins lived in Constantinople.[2]

Death of Manuel I and massacre

Following the death of Manuel I in 1180, his widow, the Latin princess Maria of Antioch, acted as regent to her infant son Alexios II Komnenos. Her regency was notorious for the favoritism shown to Latin merchants and the big aristocratic land-owners, and was overthrown in April 1182 by Andronikos I Komnenos, who entered the city in a wave of popular support.[2][12] Almost immediately, the celebrations spilled over into violence towards the hated Latins, and after entering the city's Latin quarter a raging mob began attacking the inhabitants.[4] Many had anticipated the events and escaped by sea.[3] The ensuing massacre was indiscriminate: neither women nor children were spared, and Latin patients lying in hospital beds were murdered.[4] Houses, churches, and charitable institutions were plundered.[4] Latin clergymen received special attention, and Cardinal John, the Pope's representative, was beheaded and his head was dragged through the streets at the tail of a dog.[3][13] Although Andronikos himself had no particular anti-Latin attitude, he allowed the massacre to proceed unchecked.[14] Ironically, a few years later, Andronikos I himself was deposed and handed over to the mob of Constantinople citizenry, and was tortured and summarily executed in the Hippodrome by Latin soldiers.

Impact

The massacre further worsened the image of the Byzantines in the West, and although regular trade agreements were soon resumed between Byzantium and Latin states, the underlying hostility would remain, leading to a spiraling chain of hostilities: a Norman expedition under William II of Sicily in 1185 sacked Thessalonica, the Empire's second largest city, and the German emperors Frederick Barbarossa and Henry VI both threatened to attack Constantinople.[15] The worsening relationship culminated with the brutal sack of the city of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204, which led to the permanent alienation of Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholics. The massacre itself however remains relatively obscure, and Catholic historian Warren Carroll notes that "Historians who wax eloquent and indignant - with considerable reason - about the sack of Constantinople ... rarely if ever mention the massacre of the Westerners in ... 1182."[13]

See also

- Venetian–Genoese Wars

External links

References

- ^ Gregory, Timothy (2010). A History of Byzantium. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 309. ISBN 978-1405184717.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 950-1250. Cambridge University Press. 1986. pp. 506–508. ISBN 9780521266451. http://books.google.com/books?id=1IhKYifENTMC.

- ^ a b c Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 107. ISBN 9780521428941. http://books.google.com/books?id=rymIUITIYdwC.

- ^ a b c d Vasiliev, Aleksandr (1958). History of the Byzantine Empire. 2, Volume 2. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 446. ISBN 978-0299809263.

- ^ Birkenmeier, John W. (2002). The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081–1180. BRILL. pp. 39. ISBN 9004117105.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780521428941. http://books.google.com/books?id=rymIUITIYdwC.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780521428941. http://books.google.com/books?id=rymIUITIYdwC.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–99. ISBN 9780521428941. http://books.google.com/books?id=rymIUITIYdwC.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780521428941. http://books.google.com/books?id=rymIUITIYdwC.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780521428941. http://books.google.com/books?id=rymIUITIYdwC.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2003). Enrico Dandolo & the Rise of Venice. JHU Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9780801873171. http://books.google.com/books?id=F5o3jlGTk0sC.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780521428941. http://books.google.com/books?id=rymIUITIYdwC.

- ^ a b Carroll, Warren (1993). The Glory of Christendom, Front Royal, VA: Christendom Press, pp. 157, 131

- ^ Harris, Jonathan (2006). Byzantium and the Crusades, ISBN 978-1-85285-501-7, pp. 111-112

- ^ Van Antwerp Fine, John (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780472082605. http://books.google.com/books?id=QDFVUDmAIqIC.

Categories:- 12th century in the Byzantine Empire

- Constantinople

- Massacres

- History of the Byzantine Empire

- Conflicts in 1182

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.