- Marsy's Law

-

Marsy's Law

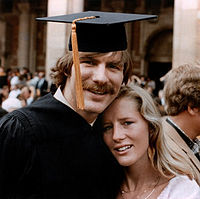

Marsy Nicholas, the inspiration of Marsy's Law

with her brother Henry Nicholas, who led the campaign to pass the Constitutional AmendmentWebsite http://ballotpedia.org/wiki/index.php/California_Proposition_9_(2008)

http://www.marsyslawforall.orgProposition 9 (or the Victims' Bill of Rights Act of 2008: Marsy's Law)[1] is an Amendment to the California Constitution enacted by California voters through the initiative process in the November 2008 state elections. The Act protects and extends the legal rights of victims of crime and, in so doing, amends not only the Constitution of California but the Penal Code.[2]

Marsy Nicholas was the sister of Henry Nicholas, the co-founder and former Co-Chairman of the Board, President and Chief Executive Officer of Broadcom Corporation. In 1983, Marsy, then a senior at UC Santa Barbara, was stalked and brutally murdered by her ex-boyfriend. Her murderer, Kerry Conley, died in prison one year before Marsy’s Law passed. Henry Nicholas became the main organizer and sponsor of the campaign to pass Marsy’s Law. Former California Gov. Pete Wilson calls Henry Nicholas the “driving force” behind the law.[3]

Since its passage, Marsy’s Law has had a major impact on the state’s judicial system, a critical result has been to dramatically increase the length of parole denials. Before Marsy’s Law, the maximum parole denial was five years for convicted murderers and two years for all other crimes. Now parole denials can be imposed for 7, 10 and even 15 years. Statistics show that last year 20% or 656 inmates received parole denials of 7 years or more. In 2009, only 3.5% received denials of two years or less.[4]

Law enforcement agencies now read victims their “Marsy Rights” just as the accused are read their Miranda Rights. Also, attorneys now receive training on Marsy’s Law, with the first such session taking place in January, 2010, at the University of California, Irvine, School of Law. Judges now rely on Marsy’s Law in making rulings and Marsy’s Law recently was cited in the mistrial of an elder abuse case because the judge found the victim had been denied due process. Marsy’s Law also has been the basis of two major lawsuits challenging the early release of prison inmates in California.[5]

Contents

Overview of the Proposal

This measure amends the state constitution and various state laws to (1) expand the legal rights of crime victims and the payment of restitution by criminal offenders, (2) restrict the early release of inmates, and (3) change the procedures for granting and revoking parole. These changes are discussed in more detail below.[6]

Expansion of the rights of victims and restitution

Background

In June 1982, California voters approved Proposition 8, known as the Victims Bill of Rights.[7]

Among other changes, the proposition amended the Constitution and various state laws to grant crime victims the right to be notified of, to attend, and to state their views at, sentencing and parole hearings. Other separately enacted laws have created other rights for crime victims, including the opportunity for a victim to obtain a judicial order of protection from harassment by a criminal defendant.

Proposition 8 established the right of crime victims to obtain restitution from any person who committed the crime that caused them to suffer a loss. Restitution often involves replacement of stolen or damaged property or reimbursement of costs that the victim incurred as a result of the crime. A court is required under current state law to order full restitution unless it finds compelling and extraordinary reasons not to do so.[8]

Sometimes, however, judges do not order restitution. Proposition 8 also established a right to “safe, secure and peaceful” schools for students and staff of primary, elementary, junior high, and senior high schools.

Changes made

Restitution. This measure requires that, without exception, restitution be ordered from offenders who have been convicted, in every case in which a victim suffers a loss. The measure also requires that any funds collected by a court or law enforcement agencies from a person ordered to pay restitution would go to pay that restitution first, in effect prioritizing those payments over other fines and obligations an offender may legally owe.[9]

Notification and participation of victims in criminal justice proceedings

As noted above, Proposition 8 established a legal right for crime victims to be notified of, to attend, and to state their views at, sentencing and parole hearings. This measure expands these legal rights to include all public criminal proceedings, including the release from custody of offenders after their arrest, but before trial. In addition, victims would be given the constitutional right to participate in other aspects of the criminal justice process, such as conferring with prosecutors on the charges filed. Also, law enforcement and criminal prosecution agencies would be required to provide victims with specified information, including details on victim’s rights.[10]

Other expansions of victims’ legal rights

This measure expands the legal rights of crime victims in various other ways, including the following:

- Crime victims and their families would have a state constitutional right to (1) prevent the release of their confidential information or records to criminal defendants, (2) refuse to be interviewed or provide pretrial testimony or other evidence requested in behalf of a criminal defendant, (3) protection from harm from individuals accused of committing crimes against them, (4) the return of property no longer needed as evidence in criminal proceedings, and (5) “finality” in criminal proceedings in which they are involved. Some of these rights now exist in statute.[11]

- The Constitution would be changed to specify that the safety of a crime victim must be taken into consideration by judges in setting bail for persons arrested for crimes.

- The measure would state that the right to safe schools includes community colleges, colleges, and universities.[12]

Restrictions on early release of inmates

Background

The state operates 33 state prisons and other facilities that had a combined adult inmate population of about 171,000 as of May 2008. The costs to operate the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) in 2008–09 are estimated to be approximately $10 billion. The average annual cost to incarcerate an inmate is estimated to be about $46,000. The state prison system is currently experiencing overcrowding because there are not enough permanent beds available for all inmates. As a result, gymnasiums and other rooms in state prisons have been converted to house some inmates.

Both the state Legislature and the courts have been considering various proposals that would reduce overcrowding, including the early release of inmates from state prison. At the time this analysis was prepared, none of these proposals had been adopted. State prison populations are also affected by credits granted to prisoners. These credits, which can be awarded for good behavior or participation in specific programs, reduce the amount of time a prisoner must serve before release.[13] Collectively, the state’s 58 counties spend over $2.4 billion on county jails, which have a population in excess of 80,000. There are currently 20 counties where an inmate population cap has been imposed by the federal courts and an additional 12 counties with a self-imposed population cap. In counties with such population caps, inmates are sometimes released early to comply with the limit imposed by the cap. However, some sheriffs also use alternative methods of reducing jail populations, such as confining inmates to home detention with Global Positioning System (GPS) devices.[14]

Changes made

This measure amends the Constitution to require that criminal sentences imposed by the courts be carried out in compliance with the courts’ sentencing orders and that such sentences shall not be “substantially diminished” by early release policies to alleviate overcrowding in prison or jail facilities. The measure directs that sufficient funding be provided by the Legislature or county boards of supervisors to house inmates for the full terms of their sentences, except for statutorily authorized credits which reduce those sentences.

Changes affecting the granting and revocation of parole

Background

The Board of Parole Hearings conducts two different types of proceedings relating to parole. First, before CDCR releases an individual who has been sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole, the inmate must go before the board for a parole consideration hearing. Second, the board has authority to return to state prison for up to a year an individual who has been released on parole but who subsequently commits a parole violation. (Such a process is referred to as parole revocation.) A federal court order requires the state to provide legal counsel to parolees, including assistance at hearings related to parole revocation charges.[15]

Changes made

Parole Consideration Procedures for Lifers. This measure changes the procedures to be followed by the board when it considers the release from prison of inmates with a life sentence. Specifically:

- Currently, individuals whom the board does not release following their parole consideration hearing must generally wait between one and five years for another parole consideration hearing. This measure would extend the time before the next hearing to between 3 and 15 years, as determined by the board. However, inmates would be able to periodically request that the board advance the hearing date.

- Crime victims would be eligible to receive earlier notification in advance of parole consideration hearings. They would receive 90 days advance notice, instead of the current 30 days.

- Currently, victims are able to attend and testify at parole consideration hearings with either their next of kin and up to two members of their immediate family, or two representatives. The measure would remove the limit on the number of family members who could attend and testify at the hearing, and would allow victim representatives to attend and testify at the hearing without regard to whether members of the victim’s family were present.

- Those in attendance at parole consideration hearings would be eligible to receive a transcript of the proceedings.

- General Parole Revocation Procedures. This measure changes the board’s parole revocation procedures for offenders after they have been paroled from prison. Under a federal court order in a case known as Valdivia v. Schwarzenegger, parolees were entitled to a hearing within 10 business days after being charged with violation of their parole to determine if there is probable cause to detain them until their revocation charges are resolved. The measure extends the deadline for this hearing to 15 days. The same court order also required that parolees arrested for parole violations have a hearing to resolve the revocation charges within 35 days. This measure extends this timeline to 45 days. The measure also provides for the appointment of legal counsel to parolees facing revocation charges only if the board determines, on a case-by-case basis, that the parolee is indigent because of the complexity of the matter or because of the parolee’s mental or educational incapacity, the parolee appears incapable of speaking effectively in his or her defense. Because this measure does not provide for counsel at all parole revocation hearings, and because the measure does not provide counsel for parolees who are not indigent, a federal judge held it was in conflict with the Valdivia court order, which requires that all parolees be provided legal counsel. However, in March, 2010, the Federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, rejected the lower court ruling and directed it to reconcile its ruling with Proposition 9.[16]

Newspaper endorsements

Editorial boards opposed

The Los Angeles Times encourages a "no" vote on 9, saying, "If the concern is protection of families from further victimization, as proponents claim, that goal can be met without granting families a new and inappropriate role in prosecutions."[17]

Other editorial boards opposed:

- Pasadena Star News.[18]

- Press Democrat.[19]

- Press Enterprise.[20]

- Tracy Press.[21]

- San Diego Union Tribune.[22]

- Orange County Register.[23]

- Sacramento Bee.[24]

- San Francisco Chronicle.[25]

- Bakersfield Californian.[26]

- La Opinion.[27]

- Fresno Bee.[28]

- Woodland Daily Democrat.[29]

- San Jose Mercury News.[30]

- Chico Enterprise-Record.[31]

- Stockton Record.[32]

- New York Times.[33]

- Contra Costa Times.[34]

- San Gabriel Valley Tribune.[35]

- Napa Valley Register.[36]

- Salinas Californian.[37]

- Monterey County Herald.[38]

- Long Beach Press-Telegram.[39]

- Desert Dispatch.[40]

- The Vacaville Reporter.[41]

- Los Angeles Daily News.[42]

- Santa Cruz Sentinel.[43]

- The Modesto Bee.[44]

Editorial boards in favor

- The Eureka Reporter.[45]

Results

Proposition 9[46] Choice Votes Percentage  Yes

Yes6,682,465 53.84% No 5,728,968 46.16% Valid votes 12,411,433 90.31% Invalid or blank votes 1,331,744 9.69% Total votes 13,743,177 100.00% Voter turnout 79.42% References

- ^ Full text of Proposition 9

- ^ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/content/statement.php

- ^ http://www.ocregister.com/articles/nicholas-245053-marsy-victims.html

- ^ http://www.euroinvestor.co.uk/news/story.aspx?id=11018785&bw=20100426005708

- ^ http://www.marsyslawforall.org/news/jan/

- ^ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/content/statement.php

- ^ www3. thestar. com/ static/ PDF/ crime/Doob_Zimring_Cal ifornia. pdf

- ^ www3. thestar. com/ static/ PDF/ crime/Doob_Zimring_Cal ifornia. pdf

- ^ http://www.alcoda.org/victim_witness/marsys_law

- ^ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/notification.php

- ^ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/content/bill_of_rights.php

- ^ http://ag.ca.gov/victimservices/content/bill_of_rights.php

- ^ Lagos, Marisa (February 18, 2010). "Rapist Moved From School Area / Residents picketed boarding house". The San Francisco Chronicle. http://articles.sfgate.com/2010-02-18/bay-area/17926727_1_early-release-early-release-crime-victims-united.

- ^ http://nicic.gov/features/statestats/?state=ca

- ^ "Marsy's Law: Crime Victims' Bill of Rights Act of 2008 Campaign Announcement". Business Wire. April 16, 2008. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0EIN/is_2008_April_16/ai_n25332817/.

- ^ http://www.cjlf.org/releases/10-10.htm

- ^ Los Angeles Times, "No on Proposition 9", September 26, 2008

- ^ Pasadena Star News, "Vote 'no' on props. 6 and 9", October 6, 2008

- ^ Press Democrat, "Wrong Way," September 8, 2008

- ^ Press Enterprise, "No on 9," September 12, 2008

- ^ Tracy Press, "Proposition 9 has victims as a concern, but it would put too much burden on our prison system if it passes," September 23, 2008.

- ^ San Diego Union Tribune, "No on Prop 9: Measure is poorly drafted and wrongheaded," September 25, 2008

- ^ Orange County Register, "California Prop. 9 Editorial: Unnecessary tinkering with constitution," October 2, 2008

- ^ Sacramento Bee, "Proposition 9", October 9, 2008

- ^ San Francisco Chronicle, "Props. 6 and 9 are budget busters," October 9, 2008.

- ^ Bakersfield Californian, "Ballot-box budgeting: Vote NO on Props 6 and 9," October 9, 2008

- ^ La Opinion, "Two Measures to Reject," October 12, 2008

- ^ Fresno Bee, "Vote 'no' on Proposition 9, an ill-considered crime victims bill," October 13, 2008.

- ^ Woodland Daily Democrat, "Voters should turn down Props. 5, 6, and 9", October 14, 2008.

- ^ San Jose Mercury News, "Editorial: Proposition 9 would increase prison costs; vote no," October 14, 2008.

- ^ Chico Enterprise-Record, "Flawed measures should be rejected," October 16, 2008.

- ^ Stockton Record, "Proposition 9 – No," October 16, 2008.

- ^ New York Times, "Fiscal Disaster in California," October 9, 2008.

- ^ Contra Costa Times, "Times recommendations on California propositions," October 19, 2008.

- ^ San Gabriel Valley Tribune, "Propositions in Review," October 19, 2008.

- ^ Napa Valley Register, Vote No On Proposition 9, October 16, 2008

- ^ Salinas Californian, "Vote no on state Props. 5, 6 and 9," October 18, 2008.

- ^ Monterey County Herald, "Proposition endorsements," October 17, 2008.

- ^ Long Beach Press-Telegram, "No on Proposition 9," October 4, 2008.

- ^ Desert Dispatch, "Victims' Rights Yes, Amendment No," October 8, 2008

- ^ The Reporter, "Vote No on Prop. 9," October 22, 2008.

- ^ Los Angeles Daily News, "No on Props. 5, 6, and 9.

- ^ Santa Cruz Sentinel, "As We See It: Vote No on Props. 6 and 9," October 15, 2008.

- ^ Modesto Bee, "Prop. 9 is too ambitious," October 9 2008.

- ^ Eureka Reporter, "The Eureka Reporter recommends," October 14, 2008

- ^ "Statement of Vote: 2008 General Election" (PDF). California Secretary of State. December 13, 2008. http://www.sos.ca.gov/elections/sov/2008_general/sov_complete.pdf.

External links

(2007 ←) California elections, 2008 (→ 2009) February primary election June primary election November general election Presidential · United States House of Representatives · State Senate · State Assembly · Propositions: 1A, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12Special elections Local elections San Francisco general (February) · San Francisco general (June) · San Francisco general (November) · San Francisco Board of SupervisorsCategories:- California ballot propositions, 2008

- Amendments to the California constitution

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.