- Shoah (film)

-

This page is about the film by the name of Shoah. For other uses, see Shoah (disambiguation)

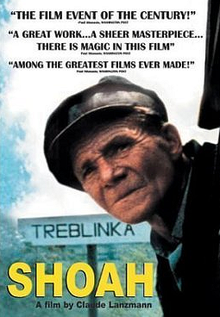

Shoah

film posterDirected by Claude Lanzmann Starring Simon Srebnik

Mordechaï Podchlebnik

Motke Zaidl

Hanna Zaidl

Jan Piwonski

Richard Glazar

Rudolf VrbaCinematography Dominique Chapuis

Jimmy Glasberg

William LubtchanskyEditing by Ziva Postec

Anna RuizDistributed by New Yorker Films Release date(s) 23 October 1985 Running time  613 mins (10 h 13 m)

613 mins (10 h 13 m)

503 mins.

503 mins.

566 mins.

566 mins.

544 mins.

544 mins.Language French

German

Hebrew

Polish

Yiddish

EnglishShoah is a 1985 French documentary film directed by Claude Lanzmann about the Holocaust (also known as the Shoah). The film primarily consists of interviews and visits to key Holocaust sites.

Contents

Synopsis

Although loosely structured, the film is concerned mainly with four topics: Chełmno, where gas vans were first used to exterminate Jews; the death camps of Treblinka and Auschwitz-Birkenau; and the Warsaw Ghetto, with testimonies from survivors, witnesses, and perpetrators.

The sections on Treblinka include testimony from Abraham Bomba, who survived as a barber, Richard Glazar, an inmate, and a rare interview with Franz Suchomel, an SS officer who worked at the camp who reveals intricate details of the camp's gas chamber. Suchomel apparently agreed to provide Lanzmann with some anonymous background details; Lanzmann instead secretly filmed his interview, with the help of assistants and a hidden camera. There is also an account from Henryk Gawkowski, who drove one of the trains while intoxicated with vodka. Gawkowski is portrayed on the photograph used on the poster.

Testimonies on Auschwitz are provided by Rudolf Vrba, who escaped from the camp before the end of the war and Filip Müller, who worked in an incinerator burning the bodies from the gassings. There are also accounts from various local villagers, who saw the trains heading daily to the camp and leaving empty; they quickly guessed the fate of those on board.

The only two Jews to survive Chelmno are interviewed: Simon Srebnik, who was forced to sing military songs to amuse the Nazis and Mordechaï Podchlebnik. There is also a secretly filmed interview with Franz Schalling, who was a guard.

The Warsaw ghetto is discussed toward the end of the film, and the conditions there are described by Jan Karski, who worked for the Polish government-in-exile and Franz Grassler, a Nazi administrator who liaised with Jewish leaders. Memories from Jewish participants in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising conclude the documentary.

Lanzmann also interviews Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg, who discusses the historical significance of Nazi propaganda against the European Jews and the Nazi invention of the Final Solution.

The complete text of the film was published in 1985.

Production

Shoah took eleven years to make, beginning in 1974.[1] The first six years of production were devoted to the recording of interviews with the individuals that appear in the film, which were conducted in 14 different countries.[1] After the shooting had been completed, editing for the film continued for five years where it was cut from 350 hours of raw footage down to the 91⁄2 hours of the final version.[1]

Archetypes in Shoah

Shoah consists of many hours of interviews with witnesses of the Holocaust. Lanzmann's style of interviewing, and his selection of interview footage divides his witnesses into three distinct archetypes: survivor, bystander and perpetrator. Lanzmann makes an effort to represent each archetype quite differently.

Survivors are those who directly experienced the persecution and horror of the Holocaust, and survived to tell their story. All of the survivors that Lanzmann interviews are Jewish. Lanzmann uses these survivors to present a historical record. Many survivors give long, detached descriptions of the events that they witnessed. For example, in Part 4, we hear Filip Müller and Rudolf Vrba describe the liquidation of the family camp at Auschwitz. Their testimonies form an historical narrative.

Other survivors tell of their own personal experiences of the Holocaust. Müller does not just describe the gassing of the prisoners from the family camp; he also talks about what the prisoners said to him, and describes the experience of going into the gas chamber himself. This testimony is a personal narrative. Lanzmann's survivors react emotionally to what they witnessed. Müller breaks down as he recalls the prisoners breaking into song while being forced into the gas chamber. The camera pulls in close, to capture every detail of his distress. Lanzmann also encourages his witnesses to act out their testimony.

In Part 3 Lanzmann interviews Abraham Bomba, a barber at Treblinka, while he cuts hair in a barber's shop. He breaks down while describing how a barber friend of his came across his wife while cutting hair outside the gas chamber. As the camera captures his anguish, Bomba's personal narrative is unspoken as well as spoken.

Bystanders are those who were present during the events of the Holocaust without directly being part of it. Some were peripherally involved while others were witnesses. All of the bystanders that Lanzmann interviews are Polish. Lanzmann procures personal narratives from these bystanders. He interviews many of them in the same way that he interviews the survivors.

In Part 1 he takes Pan Falborski, a Polish bystander, on a train to Treblinka while we watch his reaction. Lanzmann also drives him along the streets of Wlodawa in a car while he talks about the Jews who used to live in the passing houses. In Part 2 Falborski talks about the gas vans and the mass graves. Karski returns and gives a detailed, emotional description of the ghetto.

Lanzmann interviews many bystanders in public groups. He does not ask for their names or for detailed testimony. Of many bystanders he asks what they saw or heard, and whether they knew what was going on in the death camps. Their answers reveal the complicated psychology of those who saw, heard, smelled—obviously knew what was going on, but were legitimately able to justify inaction by the threat of death. It becomes numbingly obvious over many interviews that everyone knew huge numbers of people were being systematically exterminated. Yet, as one Polish peasant puts it when asked if the non-Jewish Poles were afraid for the Jews, "Let me put it this way. When you cut your finger, does it hurt me?" This same Pole, who still lives near Treblinka, tells of how they would warn Jews in passing trains that they were to be killed, by making a slitting motion across his throat. This interview is riveting, as Lanzmann tries to clarify how often he made this gesture. He answers, "To all the Jews, in principle." The manner in which he demonstrates this gesture, and the futility of it in causing anything but more pain, leaves unanswered the question of whether he did this for his own amusement, or was trying to help in any legitimate way.

In Part 2 Lanzmann talks to a group of Polish women in Grabow; they reveal that they did not like the Jewish women who used to live in Grabow because they were rich and beautiful and did not have to work. Another bystander, a man, reveals that he is happy that the Jews are gone, but would rather they had gone to Israel voluntarily than be exterminated.

In an interview outside a Catholic church, with Simon Srebnik present, bystanders state the Holocaust in terms of justice for the biblical killing of Jesus by the Jews. Again, the image of this one survivor- one of only two to come out of Chelmno -surrounded by villagers who would now invoke the tired notion that antisemitism is a legitimate response to the killing of Jesus.... Mr. Srebnik maintains his composure admirably. It raises the question of how much has really changed.

Perpetrators are those who were directly involved in orchestrating the Holocaust. All of the perpetrators that Lanzmann interviews are German. From these perpetrators, Lanzmann establishes a historical narrative. They give detailed, detached accounts of the workings of the Holocaust.

In Part 2, Franz Schalling describes the workings of Chełmno where he served as a security guard. In Parts 1, 2 and 3, Franz Suchomel talks about the workings of Treblinka where he was an SS officer. In Part 3, Walter Stier, a former Nazi bureaucrat, describes the workings of the railways. Sometimes their testimony becomes more personal. Lanzmann is also concerned with establishing their knowledge of the Holocaust. Several of his perpetrators claim ignorance of the 'final solution': Suchomel states he did not know about extermination at Treblinka until he arrived there, Stier insists he was far too busy managing railroad traffic to notice his trains were transporting Jews to their deaths.

Some subjects fail to fit neatly into any of the these three categories, like the courier to the Polish Government in Exile, Jan Karski. Karski, a Christian, sneaks into the Warsaw ghetto and then escapes to England to try to convince the Allied governments to intervene more strongly on behalf of the Jews, but fails in doing so.

Notes

- ^ a b c Austin, Guy (1996). Contemporary French Cinema: An Introduction. New York: Manchester University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0719046106.

See also

References

- Felman, Shoshana (1994). "Film as Witness: Claude Lanzmann's Shoah". In Hartman, Geoffrey. Holocaust Remembrance: The Shapes of Memory. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 1557861250.

- Hirsch, Marianne; Spitzer, Leo (1993). "Gendered Translations: Claude Lanzmann's Shoah". In Cooke, Miriam; Woollacott, Angela. Gendering War Talk. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691069808.

- Lanzman, Claude (1985). Shoah. New Yorker Films.

- Loshitzky, Yosefa (1997). "Holocaust Others: Spielberg's Schindler's List verses Lanzman's Shoah". In Loshitzky, Yosefa. Spielberg's Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler's List. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 025333232X.

External links

- Official website

- Shoah at AllRovi

- Shoah at Box Office Mojo

- Shoah at the Internet Movie Database

- Shoah at Metacritic

- Shoah at Rotten Tomatoes

- SHOAH - Claude Lanzmann's revised 2007 edition

- Ziva Postec - Lanzmann's Editor of Shoah

- [1] Extracts from Shoah footage

Categories:- 1985 films

- Documentary films about the Holocaust

- Films directed by Claude Lanzmann

- French documentary films

- 1980s documentary films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.