- Nuclear weapons and the United Kingdom

-

United Kingdom Nuclear program start date 10 April 1940 First nuclear weapon test 2 October 1952 First fusion weapon test 15 May 1957 Last nuclear test 26 November 1991 Largest yield test 3 Mt (13 PJ) (28 April 1958) Total tests 45 detonations Peak stockpile 350 warheads (1970s) Current stockpile 225 warheads[1] Maximum missile range 13,000 km (7,000 nmi or 8,100 mi) NPT signatory Yes (1968, one of five recognised powers) Nuclear weapons

History

Warfare

Arms race

Design

Testing

Effects

Delivery

Espionage

Proliferation

Arsenals

Terrorism

Anti-nuclear oppositionNuclear-armed states United States · Russia

United Kingdom · France

China · India · Israel

Pakistan · North Korea

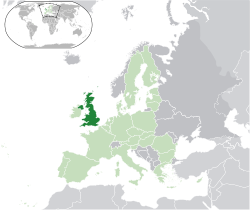

South Africa (former)The United Kingdom was the third country to test an independently developed nuclear weapon, in October 1952. It is one of the five "Nuclear Weapons States" (NWS) under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which the UK ratified in 1968. The UK is currently thought to retain a weapons stockpile of around 160 operational nuclear warheads and 225 nuclear warheads in total but has refused to declare exact size of its arsenal. [2]

Since the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement, the United States and the United Kingdom have cooperated extensively on nuclear security matters. The special relationship between the two countries has involved the exchange of classified scientific information and nuclear materials such as plutonium. The UK has not run an independent nuclear weapons delivery system development and production programme since the cancellation of the Blue Streak missile in the 1960s, instead it has pursued joint development (for its own use) of US delivery systems, designed and manufactured by Lockheed Martin, and fitting them with warheads designed and manufactured by the UK's Atomic Weapons Research Establishment and its successor the Atomic Weapons Establishment. In 1974 a US proliferation assessment noted that "In many cases [Britain's sensitive technology in nuclear and missile fields] is based on technology received from the US and could not legitimately be passed on without US permission."[3]

In contrast with the other permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, the United Kingdom currently operates only a single nuclear weapon delivery system since decommissioning its tactical WE.177 free-falling nuclear bombs in 1998. The present system consists of four Vanguard class submarines based at HMNB Clyde, armed with up to 16 Trident missiles, which each carry nuclear warheads in up to eight MIRVs, performing both strategic and sub-strategic deterrence roles.

While a firm decision has yet to be taken on the replacement of the UK's nuclear weapons, the manufacturer of the UK's warheads, AWE, is currently undertaking research which is largely dedicated to providing new warheads[4] and on 4 December 2006 the then Prime Minister Tony Blair announced plans for a new class of nuclear missile submarines.[5]

Number of warheads

Faslane Naval Base, HMNB Clyde, Scotland. Home of the Vanguard class submarines which carry the UK's current nuclear arsenal.

Faslane Naval Base, HMNB Clyde, Scotland. Home of the Vanguard class submarines which carry the UK's current nuclear arsenal.

In the Strategic Defence Review published in July 1998, the United Kingdom government stated that once the Vanguard submarines became fully operational (the fourth and final one, Vengeance, entered service on 27 November 1999), it would "maintain a stockpile of fewer than 200 operationally available warheads".[6] The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute has estimated the figure as about 165, consisting of 144 deployed weapons plus an extra 15 percent as spares.[7]

At the same time, the UK government indicated that warheads "required to provide a necessary processing margin and for technical surveillance purposes" were not included in the "fewer than 200" figure.[8] However, as recently declassified archived documents on Chevaline make clear, the 15% excess (referred to by SIPRI as for spares) is normally intended to provide the 'necessary processing margin', and 'surveillance rounds do not contain any nuclear material, being completely inert. These surveillance rounds are used to monitor deterioration in the many non-nuclear components of the warhead, and are best compared with inert training rounds. The SIPRI figures correspond accurately with the official announcements and are likely to be the most accurate. The Natural Resources Defense Council speculates that a figure of 200 is accurate to within a few tens.[9] In 2008 the National Audit Office stated that the UK stockpile was of fewer than 160 operationally available nuclear warheads.[10] During a debate on the Queen's Speech on 26 May 2010 Foreign Secretary William Hague reiterated that the UK has no more than 160 operationally available warheads, and announced that the total number will not exceed 225.[11]

Weapons tests

Different sources give the number of test explosions that the UK has conducted as either 44[12][13] or 45.[14][15] The 24 tests from December 1962 onwards were in conjunction with the United States at the Nevada Test Site[16][17] with the final test being the Julin Bristol shot which took place on 26 November 1991.[18] The apparently low numbers of UK tests is misleading when compared to the large numbers of tests carried out by the US, the Soviet Union, China, and especially France; because the UK has had extensive access to US test data, obviating the need for UK tests: and an added factor is that many tests required are for 'weapon effects tests'; tests not of the nuclear device itself, but of the nuclear effects on hardened components designed to resist ABM attack. Numerous such 'effects' tests were done in support of the Chevaline programme especially; and there is some evidence that some were permitted for the French programme to harden their RVs and warheads; because most French tests being under the ocean floor, access to measure 'weapon effects' was nigh impossible.[19] An independent test programme would see the UK numbers soar to French levels. The UK government signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty on 5 August 1963[20] along with the United States and the Soviet Union which effectively restricted it to underground nuclear tests by outlawing testing in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. The UK signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty on 24 September 1996[21] and ratified it on 6 April 1998,[22] having passed the necessary legislation on 18 March 1998 as the Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Act 1998.

Nuclear defence

Warning systems

This solid-state phased array radar at RAF Fylingdales in North Yorkshire is a UK-controlled early warning station and part of the American-controlled Ballistic Missile Early Warning System.

This solid-state phased array radar at RAF Fylingdales in North Yorkshire is a UK-controlled early warning station and part of the American-controlled Ballistic Missile Early Warning System. See also: Four minute warning, RAF Fylingdales, Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, and National Missile Defense

See also: Four minute warning, RAF Fylingdales, Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, and National Missile DefenseThe UK has relied on the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) and, in later years, Defense Support Program (DSP) satellites for warning of a nuclear attack. Both of these systems are owned and controlled by the United States, although the UK has joint control over UK based systems. One of the four component radars for the BMEWS is based at RAF Fylingdales in North Yorkshire.

In 2003 the UK government stated that it will consent to a request from the US to upgrade the radar at Fylingdales for use in the US National Missile Defense system.[23]

Nevertheless, missile defence is not currently a significant political issue within the UK. The ballistic missile threat is perceived to be less severe, and consequently less of a priority, than other threats to its security.[24]

Attack scenarios

During the Cold War, a significant effort by government and academia was made to assess the effects of a nuclear attack on the UK. A major government exercise, Square Leg, was held in September 1980 and involved around 130 warheads with a total yield of 200 megatons of TNT (840 PJ). This is probably the largest attack that the apparatus of the nation state could survive in some limited form. Observers have speculated that an actual exchange would be much larger with one academic describing a 200-megaton attack as an "extremely low figure and one which we find very difficult to take seriously".[25] In the early 1980s it was thought an attack causing almost complete loss of life could be achieved with the use of less than 15% of the total nuclear yield available to the Soviets.[25]

Civil defence

Main articles: civil defence and Protect and SurviveDuring the cold war, various governments developed civil defence programmes aimed to prepare civilian and local government infrastructure for a nuclear strike on the UK. A series of seven Civil Defence Bulletin films were produced in 1964; and in the 1980s the most famous such programme was probably the series of booklets and public information films entitled Protect and Survive.

“ If the country was ever faced with an immediate threat of nuclear threat or complete annihilation, a copy of this booklet would be distributed to every household as part of a public information campaign which would include announcements on television and radio and in the press. The booklet has been designed for free and general distribution in that event. It is being placed on sale now for those who wish to know what they would be advised to do at such a time.[26] ” The booklet contained information on building a nuclear refuge within a so-called 'fall out room' at home, sanitation, limiting fire hazards and descriptions of the audio signals for attack warning, fallout warning and all clear. It was anticipated that families might need to stay within the fall-out room for up to fourteen days after an attack almost without leaving it at all.

The government also prepared a recorded announcement which was to have been broadcast by the BBC if a nuclear attack ever did occur.[27]

Sirens left over from the London Blitz during World War II[citation needed] were also to be used to warn the public. The system was mostly dismantled in 1993.

Weapons programmes

See also History of nuclear weapons

The United Kingdom worked in partnership with the United States and Canada on the Manhattan Project, resulting in the development of the first nuclear weapons, and the first-ever nuclear detonation at the Trinity test of 16 July 1945.

The United Kingdom worked in partnership with the United States and Canada on the Manhattan Project, resulting in the development of the first nuclear weapons, and the first-ever nuclear detonation at the Trinity test of 16 July 1945.

Tube Alloys and Manhattan Project

Main articles: Tube Alloys and Manhattan ProjectThe United Kingdom's nuclear weapons had their genesis in the Second World War when two recently exiled atomic scientists, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls wrote a memorandum on the construction of "a radioactive super-bomb". Forwarded to the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), the secret MAUD Committee to evaluate the possibilities was soon set up.[28] British scientists worked initially alone on the atomic bomb under the cover name of Tube Alloys, later becoming a partner in the tri-national Manhattan Project under the Quebec Agreement. The Manhattan Project resulted in the two nuclear weapons dropped over Japan.

Post-war development programme

The United Kingdom started independently developing nuclear weapons again shortly after the war. Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee set up a cabinet sub-committee, the Gen 75 Committee (GEN.75) (known informally as the "Atomic Bomb Committee"), to examine the feasibility as early as 29 August 1945. It was US refusal to continue nuclear cooperation with the UK after World War II (due to the McMahon Act of 1946 restricting foreign access to US nuclear technology) which eventually prompted the building of a bomb:

“ In October 1946, Attlee called a small cabinet sub-committee meeting to discuss building a gaseous diffusion plant to enrich uranium. The meeting was about to decide against it on grounds of cost, when [Ernest] Bevin arrived late and said "We've got to have this thing. I don't mind it for myself, but I don't want any other Foreign Secretary of this country to be talked at or to by the Secretary of State of the US as I have just been... We've got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs ... We've got to have the bloody Union Jack on top of it." [29] ” The committee, under pressure from Hugh Dalton and Sir Stafford Cripps to opt out of building the bomb due to its cost, eventually decided to go ahead not just because of considerations of Britain's prestige but also because of the likely industrial importance of atomic energy.[30]

A nuclear programme started in 1946 under the control of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment (incorporated into the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) in 1954), that was civilian in character, but was also tasked with the job of producing the fissile material, initially only plutonium 239, that was expected to be required for a military programme. It was based on a former airfield, Harwell, Berkshire; and a former Royal Ordnance Factory, Risley in Cheshire. Risley became the headquarters of the Industrial Division of UKAEA, and there were other sites under its control, notably the Calder Hall reactors at Windscale (later Sellafield) used to produce weapons grade Pu-239. The first nuclear pile in the UK, GLEEP, went critical at Harwell on 15 August 1947. AWRE was established at Aldermaston by the Ministry of Supply; later becoming the Weapons Division of the (civilian) UKAEA, before being subsumed into the Ministry of Defence in the 1970s.

William Penney, a physicist specialising in hydrodynamics was asked in October 1946 to prepare a report on the viability of building a UK weapon. Joining the Manhattan project in 1944, he had been in the observation plane Big Stink over Nagasaki, and had also done damage assessment on the ground following Japan's surrender. He had subsequently participated in the American Operation Crossroads test at Bikini Atoll. As a result of his report, the decision to proceed was formally made on 8 January 1947 at a meeting of the GEN.163 committee of six cabinet members, including Prime Minister Clement Attlee with Penney appointed to take charge of the programme.

The project was hidden under the name High Explosive Research or HER and was based initially at the Ministry of Supply's Armament Research and Development Establishment (ARDE) at Fort Halstead in Kent,[31] but in 1950 moved to a new site at AWRE Aldermaston in Berkshire. A particular problem was the McMahon Act. Although British scientists knew the areas of the Manhattan Project in which they had worked well, they only had the sketchiest details of those parts which they were not directly involved in. With the start of the Cold War there had been some warming of nuclear relations between the UK and US governments, which led to hopes of American cooperation. However these were quickly dashed by the arrest in early 1950 of Klaus Fuchs, a Soviet spy working at Harwell. Plutonium production reactors were based at Windscale, later known as Sellafield in Cumberland and construction began in September 1947, leading to the first plutonium metal ready in March 1952.

First test and early systems

The UK's first nuclear test, Operation Hurricane, in 1952.

The UK's first nuclear test, Operation Hurricane, in 1952.

A Blue Danube bomb. The airman that stood alongside to give the photograph some scale has been cropped from this picture. The girder from which the weapon is suspended would measure at least six feet (2 m) from ground level. The first Blue Danube weapons issued to the RAF were of 10–12-kiloton-of-TNT (42–50 TJ) yield, approximately the same yield as the Hiroshima bomb, although that was much smaller, being of a gun-type, whereas Blue Danube was of the implosion type similar to the Nagasaki bomb. This Blue Danube airframe design was used to house all the devices detonated at Christmas Island in the Operation Grapple tests.

A Blue Danube bomb. The airman that stood alongside to give the photograph some scale has been cropped from this picture. The girder from which the weapon is suspended would measure at least six feet (2 m) from ground level. The first Blue Danube weapons issued to the RAF were of 10–12-kiloton-of-TNT (42–50 TJ) yield, approximately the same yield as the Hiroshima bomb, although that was much smaller, being of a gun-type, whereas Blue Danube was of the implosion type similar to the Nagasaki bomb. This Blue Danube airframe design was used to house all the devices detonated at Christmas Island in the Operation Grapple tests.

The first UK weapon test, Operation Hurricane, was detonated below the frigate HMS Plym anchored in the Monte Bello Islands on 2 October 1952. This led to the first deployed weapon, the Blue Danube free-fall bomb, in November 1953. It was very similar to the American Mark 4 weapon in having a 60-inch (1,500 mm) diameter, 32 lens implosion system with a levitated core suspended within a natural uranium tamper. The warhead was contained within a bomb casing measuring 62 inches (1.6 m) diameter and 24 feet (7.3 m) long, and being so large, could only be carried by the V-Bomber fleet.

A nuclear landmine dubbed Brown Bunny, later Blue Bunny, and finally Blue Peacock that used the Blue Danube warhead was developed from 1954 with the goal of deployment in the Rhine area of Germany. The system would have been set to an eight-day timer in the case of invasion of Western Europe by the Soviets but was cancelled in February 1958 with only two built. It was judged that the risks posed by the nuclear fallout and the political aspects of preparing for destruction and contamination of allied territory were simply too high to justify. A more usual reason for cancellation revealed by numerous archived declassified documents was that the Army felt it was too unwieldy and diverted their efforts into a successor, Violet Vision, based on the smaller successor to Blue Danube, Red Beard. None were ever built, the Army instead receiving US ADMs or Atomic Demolition Munitions under the established procedures for supply of NATO allies from US stocks held in US custody in Europe. A sea mine based on the Blue Danube warhead and codenamed Cudgel was also envisaged for delivery by midget submarines, referred to by naval sources as "sneak craft"; perhaps reflecting a belief that these craft were really rather ungentlemanly methods of waging war. None were built.

A gaseous diffusion plant was built at Capenhurst, near Chester and started production in 1953 producing low enriched uranium (LEU). By 1957 it was capable of annually producing 125 kg of highly enriched uranium (HEU). The capacity was further increased and by 1959 it may have been producing as much as 1600 kg per year.[32] At the end of 1961, having produced between 3.8 and 4.9 tonnes of HEU it was switched over to LEU production for civil use. Additional plutonium production was provided by eight electricity generating Magnox reactors at Calder Hall and Chapelcross which started operating in 1956 and 1959 respectively.

Thermonuclear weaponry

The detonation by both the US and the Soviet Union of thermonuclear devices alarmed the UK government of Winston Churchill and a decision was made on 27 July 1954 to begin development of a thermonuclear bomb, making use of the more powerful nuclear fusion reaction rather than nuclear fission. There was little or no dissent in the House of Commons.

“ The press, including those papers often most critical of the government, also supported the government's policy. The Manchester Guardian thought the decision sound, and believed that the government was right to build up a powerful deterrent, especially in the absence of a close partnership with the United States. The paper did, however, criticise the government for relying on developing bombers rather than missiles to carry the weapons.[33] ”  A Blue Danube bomb released from a Valiant bomber at 500 knots (260 m/s) at 45,000 feet (14,000 m) would accelerate to a terminal speed of 2,100 feet per second (640 m/s or Mach 2.2). In this photo the fins are not yet extended to 1.6 times diameter to quickly stabilise the bomb into a predictable ballistic trajectory. Fuzing was by means of a barometric 'gate' to switch on the radar altimeter controlled firing circuit powered by 6-volt lead-acid accumulators. These bomb casings were used for all the air-drop tests at Christmas Island and Maralinga, Australia. Detonation was approximately 52 seconds after release from the aircraft.

A Blue Danube bomb released from a Valiant bomber at 500 knots (260 m/s) at 45,000 feet (14,000 m) would accelerate to a terminal speed of 2,100 feet per second (640 m/s or Mach 2.2). In this photo the fins are not yet extended to 1.6 times diameter to quickly stabilise the bomb into a predictable ballistic trajectory. Fuzing was by means of a barometric 'gate' to switch on the radar altimeter controlled firing circuit powered by 6-volt lead-acid accumulators. These bomb casings were used for all the air-drop tests at Christmas Island and Maralinga, Australia. Detonation was approximately 52 seconds after release from the aircraft.

The Economist, the New Statesman and many left-wing newspapers supported the government's policy of nuclear deterrence as a means of reducing the size of conventional forces. Their view (in 1954-55) is fairly summarised as being not opposed to nuclear deterrence and nuclear weapons, but in their view that of the United States would suffice, and that of the costs of the 'nuclear umbrella' was best left to be borne by the United States alone. Their attitudes to nuclear weapons have changed somewhat since then.[34]

The first prototype, Short Granite, was detonated on 15 May 1957 in Operation Grapple, with disappointing results at 300 kilotons of TNT (1.3 PJ), when the target requirement was 1 Mt (4.2 PJ). A further test of Purple Granite yielded less at 200 kt (0.84 PJ). Further testing in 1958 got performance up to the requirement, but none were ever deployed, because the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement intervened, making fully developed and Service engineered designs available more quickly, and more cheaply. The first of these was the US Mk-28 weapon which was anglicised and manufactured in the UK as Red Snow and quickly deployed as Yellow Sun Mk.2 in the V-bomber fleet. Red Snow became the warhead of choice for the Blue Steel stand-off missile and some of the Skybolt missiles intended for carriage by the V-bombers. Under the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement 5.4 tonnes of UK produced plutonium was sent to the US in return for 6.7 kg of tritium and 7.5 tonnes of HEU over the period 1960-1979, replacing Capenhurst production, although much of the HEU was used not for weapons, but as fuel for the growing UK fleet of nuclear submarines, both of the Polaris variety and others numbering approx twelve.

Fifty-eight Blue Danube bombs were produced, although archived declassified files indicate that only a small proportion of these were ever serviceable at any one time. It remained in service until 1963, when it was replaced by Red Beard, a smaller tactical boosted fission weapon that used the same fissile core as Blue Danube and was deployed on many smaller aircraft than the V-bombers, both ashore and at sea aboard five carriers. Stocks of Red Beard were maintained in Cyprus, Singapore, and a smaller number in the UK. After the detonation of US and Soviet thermonuclear weapons the UK deployed an Interim Megaton Weapon in the V-bomber fleet until a true thermonuclear weapon could be devised from the Christmas Island tests. This never tested interim weapon derived from the Orange Herald warhead tested at Christmas Island on 31 May 1957 yielding 720 kt (3.0 PJ)[35] known as Green Grass was merely a very large unboosted pure fission weapon yielding 400 kt (1.7 PJ). It was the largest pure fission weapon ever deployed by any nuclear state. Green Grass was deployed first in a modified Blue Danube casing and known as Violet Club. A later variant was deployed in a Yellow Sun Mk.1 casing. A true thermonuclear device was planned for the later Yellow Sun Mk.2 bomb, and after the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement the choice fell on a US Mk.28 warhead manufactured in the UK and known as Red Snow. This Red Snow warhead was also fitted in the Blue Steel, an air-launched stand-off missile which remained in service until Dec 1970. It was to have been replaced by Skybolt air-launched ballistic missiles purchased from the United States. In 1962 and 1960 respectively the UK cancelled their Blue Steel extended range upgrade (Blue Steel Mk2)and Blue Streak missile projects. It was asserted in Parliament at the time that the Blue Streak missiles were cancelled because of their vulnerability to Soviet attack as they were liquid fuelled an immobile, although this vulnerability was in fact negligible. However, the main aim in British policy had changed from one of independence to interdependence- subsequently the Macmillan Government favoured the purchase of Skybolt missiles from the United States to the continuation of an independent project. Similarly, reassessments of Soviet capabilities changed military perceptions and led to the removal of Thor IRBM missiles in the UK; and Jupiter IRBMs in Italy and Turkey; although the Turkish sites were implicated in an alleged deal following the Cuban Missile Crisis. To consternation, and considerable protests, the incoming Kennedy administration cancelled Skybolt at the end of 1962 because it was believed by the US Secretary of State for Defense, Robert McNamara, that other delivery systems were progressing better than expected, and a further expensive system was surplus to US requirements.

The Polaris A1 or A2 missile, seen here on a launch pad in Cape Canaveral, was a submarine-launched ballistic missile purchased from the US. The UK purchased the A3T variant, the final production model, that incorporated hardened missile electronic components to resist ABM attack in the boost phase, although neither the three re-entry vehicles or UK-manufactured warheads were hardened, leading to the Chevaline programme.

The Polaris A1 or A2 missile, seen here on a launch pad in Cape Canaveral, was a submarine-launched ballistic missile purchased from the US. The UK purchased the A3T variant, the final production model, that incorporated hardened missile electronic components to resist ABM attack in the boost phase, although neither the three re-entry vehicles or UK-manufactured warheads were hardened, leading to the Chevaline programme.

Polaris

After the cancellation of Skybolt, the UK purchased Polaris missiles for use in UK-built ballistic missile submarines. The agreement between US President John F. Kennedy and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Harold Macmillan, the Polaris Sales Agreement, was announced on 21 December 1962 and HMS Resolution sailed on her first Polaris-armed patrol on 14 June 1968.[36] In the 1970s the UK Polaris RVs and warheads were vulnerable to the Soviet ABM screen concentrated around Moscow, and the UK developed a Polaris improved-front-end (IFE) codenamed Chevaline, designed to counter this ABM defence which threatened to completely nullify an independent UK deterrent posture. When Chevaline became public knowledge in 1980, it generated huge controversy as it had been kept secret by the four governments of Wilson, Heath, Wilson (again) and Callaghan, whilst costs rocketed; admittedly during a period of high inflation; until disclosed by the Thatcher government. By the time it entered service in 1982 it had cost approx £1bn. The final Polaris/Chevaline patrol took place in 1996, two years after the first Trident-carrying submarine sailed on its first patrol.

As well as the establishment at Aldermaston, the UK nuclear weapons programme also has a factory at Burghfield nearby which assembled the weapons and is responsible for their maintenance, and had another in Cardiff which fabricated non-fissile components and a 2000 acre (8 km²) test range at Foulness. Since 1993 the sites have been managed by private consortia. The Foulness and Cardiff facilities closed in October 1996 and February 1997 respectively.

Trident

Main article: UK Trident programme HMS Vanguard, one of four Vanguard class ballistic missile submarines of the Royal Navy, which serve as the UK's nuclear delivery system.

HMS Vanguard, one of four Vanguard class ballistic missile submarines of the Royal Navy, which serve as the UK's nuclear delivery system.

WE.177 air-launched nuclear bomb

WE.177 air-launched nuclear bomb

The UK currently has four Vanguard class submarines based at HMNB Clyde in Scotland, armed with nuclear-tipped Trident missiles. The principle of operation is based on maintaining deterrent effect by always having at least one submarine at sea, and was designed for the Cold War period. One submarine is normally undergoing maintenance and the remaining two in port or on training exercises. It has been suggested that the UK's ballistic missile submarine patrols are coordinated with those of the French.[37]

Each submarine carries 16 Trident II D-5 missiles, which can each carry up to twelve warheads. However, the UK government announced in 1998 that each submarine would carry only 48 warheads, an increase of 50% over the 32 warheads carried by Trident's predecessor, Chevaline, (halving the limit specified by the previous government), which is an average of three per missile. However one or two missiles per submarine are probably armed with fewer warheads for "sub-strategic" use causing others to be armed with more; but this is speculative.

The UK-designed warheads are thought to be selectable between 0.3, 5-10 and 100 kt (1.3, 21–42 and 420 TJ); the yields obtained using either the unboosted primary, the boosted primary, or the entire "physics package"; although it must be stressed that these yields and similar data are entirely speculative. The true position is unlikely to be known with certainty for many years; as was the case with the misplaced speculation about the earlier Chevaline programme; only now becoming publicly known. Although the UK designed, manufactured and owns the warheads, there is evidence that the warhead design is similar to, or even based on, the US W76 warhead fitted in some US Navy Trident missiles, with design data being supplied by the United States through the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement.[38][39] The United Kingdom owns 58 missiles which are shared in a joint pool with the United States government and these are exchanged when requiring maintenance with missiles from the United States Navy's own pool and vice versa.

Until August 1998, the UK also retained the WE.177 nuclear weapon manufactured in the mid-1960s to late 1970s, in air-dropped free-fall bomb and depth charge versions.[40] This left the four Vanguard class submarines, which replaced the Polaris ones in the early 1990s, as the United Kingdom's only nuclear weapons platform. It has been estimated by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that the United Kingdom has built around 1,200 warheads since the first Hurricane device of 1952. In terms of number of warheads, the UK arsenal was at its maximum size of about 350 in the 1970s, but this figure does not include the large numbers of US-owned warheads, bombs, nuclear depth bombs supplied from US stocks in Europe for use by NATO allies. At its peak, these numbered 327 for the British Army of the Rhine in Germany alone.

Replacement for Trident

Main article: British replacement of the Trident systemA decision on the replacement of Trident was made on 4 December 2006. Tony Blair (Prime Minister at that time) told MPs it would be "unwise and dangerous" for the UK to give up its nuclear weapons. He outlined plans to spend up to £20bn on a new generation of submarines for Trident missiles.

He said submarine numbers may be cut from four to three, while the number of nuclear warheads would be cut by 20% to 160. Mr Blair said although the Cold War had ended, the UK needed nuclear weapons, as no-one could be sure another nuclear threat would not emerge in the future.

Deployment of US tactical nuclear weapons

Until 1992 UK forces also deployed US tactical nuclear weapons as part of a US-UK dual-key NATO nuclear sharing role.[41][42] This arrangement commenced in 1958 as Project E to provide nuclear weapons to the RAF prior to a sufficient number of Britain's own nuclear weapons becoming available.

The weapons deployed included nuclear artillery, nuclear demolition mines and warheads for Corporal and Lance missiles in Germany; theatre nuclear weapons on RAF aircraft;[43] Mark 101 nuclear depth bombs on RAF Shackleton maritime patrol aircraft, later replaced by a modern successor, the B-57 deployed on RAF Nimrod aircraft.

The Lance missiles were purchased in 1975,[44] to replace Honest John missiles which had been bought in 1960;[45][46] and were themselves a replacement for the US Corporal missiles deployed in Germany by the Royal Artillery. Not generally recognised is the fact that the Royal Artillery deployed a numerically greater quantity of US nuclear weapons than the RAF and Royal Navy combined, peaking at 277 in 1976-78; with a further 50 ADMs deployed with another British Army unit, the Royal Engineers, peaking in 1971-81.[47] The dual-key agreement for controlling US tactical nuclear weapons, known as the Heidelberg Agreement, was made on 30 August 1961. The UK sponsored access for the Canadian Army Honest John missile deployments to the US/UK nuclear warhead storage sites.[48]

The UK continues to permit the US to deploy nuclear weapons from its territory, the first having arrived in 1954.[49] During the 1980s nuclear armed USAF Ground Launched Cruise Missiles were deployed at RAF Greenham Common and RAF Molesworth. As of 2005 it is believed that approximately 110 tactical B61 nuclear bombs are stored at RAF Lakenheath for deployment by USAF F-15E Strike Eagle aircraft.[50]

Research and development facilities

Atomic Weapons Establishment, Aldermaston

Main article: Atomic Weapons EstablishmentThe Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE), Aldermaston (formerly the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment, Aldermaston) is situated just 7 miles (11 km) north of Basingstoke and approximately 14 miles (23 km) south-west of Reading, Berkshire, near a village called Aldermaston, bordering with Tadley. It was built in 1949 on the site of a former World War II Royal Air Force base and converted to nuclear weapons research, design and development in the 1950s. Although some early test devices were probably assembled on this site, final assembly of Service-engineered weapons takes place at the nearby site of Burghfield.

Royal Ordnance Factories, Cardiff and Burghfield

Main articles: Royal Ordnance Factory, ROF Burghfield, and ROF CardiffOther nuclear weapons sites could be found in Cardiff and Burghfield near Reading, Berkshire. These were the only two Royal Ordnance Factories (ROFs) not privatised in the 1980s.

ROF Cardiff, which closed in 1997, was involved in nuclear weapons programmes since 1961. The site was used for the task of recycling old nuclear weapons and precisely shaping uranium 235 (U235) and metallic beryllium components for the boosted fission devices used as primaries or 'triggers' in modern thermonuclear weapons.[51] ROF Burghfield was a former Filling Factory, opened in 1942, and run as an Agency Factory, by Imperial Tobacco, to fill Oerlikon 20 mm ammunition.[52]

Politics, decision making and nuclear posture

Anti-nuclear movement

Main article: Anti-nuclear movement in the United Kingdom The now-familiar peace symbol was originally the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament logo.

The now-familiar peace symbol was originally the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament logo.

The anti-nuclear movement in the United Kingdom consists of groups who oppose nuclear technologies such as nuclear power and nuclear weapons. Many different groups and individuals have been involved in anti-nuclear demonstrations and protests over the years.

One of the most prominent anti-nuclear groups in the UK is the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). CND's Aldermaston Marches began in 1958 and continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches. One significant anti-nuclear mobilization in the 1980s was the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp. In London, in October 1983, more than 300,000 people assembled in Hyde Park as part of the largest protest against nuclear weapons in British history. In 2005 in Britain, there were many protests about the government's proposal to replace the aging Trident weapons system with a newer model.

Nuclear posture

UK nuclear posture during the cold war was informed by interdependence with the United States. Operational control of the UK Polaris force was assigned to SACLANT, while targeting policy for its missiles was determined, as for the V-bomber force before it, by NATO's SACEUR, while maintaining an independent wholly UK targeting policy for some circumstances when a critical national emergency required it to be used alone, without the UK's NATO allies.[53][54] In these circumstances, the 'Moscow criterion' referred to the ability of the UK to strike back at the highly centralised Soviet decision-making apparatus concentrated in the Moscow area, intended to destroy the ability of the Soviet leadership to remain in control of a Soviet Union otherwise untouched. The early beginnings of studies to increase the likelihood of successful penetration of the Polaris warheads to Moscow can be traced back to 1964,[55] before the Polaris system was deployed, in order to preserve this capability in the face of anti-ballistic missile batteries around Moscow. These studies later materialised as Chevaline.[56][57]

The UK has relaxed its nuclear posture since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Labour government's 1998 Strategic Defence Review made a number of reductions from the plans announced by the previous Conservative government:[58]

- The stockpile of "operationally available warheads" was reduced from 300 to "less than 200"

- The final batch of missile bodies would not be purchased, limiting the fleet to 58.

- A submarine's load of warheads were reduced from 96 to 48. This reduced the explosive power of the warheads on a Vanguard class Trident submarine to "one third less than a Polaris submarine armed with Chevaline." However 48 warheads per Trident submarine represents a 50% increase on the 32 warheads per submarine of Chevaline. Total explosive power has been in decline for decades as the accuracy of missiles has improved, therefore requiring less power to destroy each target. Trident can destroy 48 targets per submarine, as opposed to 32 targets that could be destroyed by Chevaline.

- Submarines missiles would not be targeted, but rather at several days "notice to fire".

- Although one submarine would always be on patrol it will operate on a "reduced day-to-day alert state". A major factor in maintaining a constant patrol is to avoid "misunderstanding or escalation if a Trident submarine were to sail during a period of crisis."

Current UK posture as outlined in the Strategic Defence Review of 1998[59] is as it has been for many years. Only the delivery methods have changed. Trident SLBMs still provide the long-range strategic element as they have done for some years. Until 1998 the free-fall WE.177A, WE.177B and WE.177C bombs provided an aircraft-delivered sub-strategic option in addition to their designed function of tactical battlefield weapons. With the retirement of WE.177, a sub-strategic warhead is stated by Ministers to be incorporated into some (but not all) Trident missiles deployed. The exact mix of weapons on each submarine is unknown as is the numbers and warhead yield. Current UK thinking[citation needed] is that the capacity to launch a very limited strike is a more credible deterrent in the current world situation than use of a MIRVed strategic system.

Nuclear weapons control

The precise details of how a British Prime Minister would authorise a nuclear strike remain secret, although the principles of the Trident control system is believed to be based on the plan set up for Polaris in 1968, which has now been declassified. A closed-circuit television system was set up between 10 Downing Street and the Polaris Control Officer at the Northwood Headquarters of the Royal Navy. Both the Prime Minister and the Polaris Control Officer would be able to see each other on their monitors when the command was given. If the link failed – for instance during a nuclear attack or when the PM was away from Downing Street – the Prime Minister would send an authentication code which could be verified at Northwood. The Commander in Chief would then broadcast a firing order to the Polaris submarines via the Very Low Frequency radio station at Rugby. The UK has not deployed control equipment requiring codes to be sent before weapons can be used, such as the U.S. Permissive Action Link, which if installed would preclude the possibility that military officers could launch British nuclear weapons without authorisation.

Until 1998, when it was withdrawn from service, the WE.177 bomb was armed with a standard tubular pin tumbler lock (as used on bicycle locks) and a standard allen key was used to set yield and burst height. Currently, British Trident commanders are able to launch their missiles without authorisation, whereas their American colleagues cannot. At the end of the Cold War the U.S. Fail Safe Commission recommended installing devices to prevent rogue commanders persuading their crews to launch unauthorised nuclear attacks. This was endorsed by the Nuclear Posture Review and Trident Coded Control Devices were fitted to all U.S. SSBNs by 1997. These devices prevented an attack until a launch code had been sent by the Chiefs of Staff on behalf of the President. The UK took a decision not to install Trident CCDs or their equivalent on the grounds that an aggressor might be able to wipe out the British chain of command before a launch order had been sent.[60][61][62]

In December 2008 BBC Radio 4 made a programme titled The Human Button, providing new information on the manner in which the United Kingdom could launch its nuclear weapons, particularly relating to safeguards against a rogue launch. Former Chief of the Defence Staff (most senior officer of all British armed forces) and Chief of the General Staff (most senior officer in the British Army), General Lord Guthrie of Craigiebank, explained that the highest level of safeguard was against a prime minister ordering a launch without due cause: Lord Guthrie stated that the constitutional structure of the United Kingdom provided some protection against such an occurrence, as while the Prime Minister is the chief executive and so practically commands the armed services, the ultimate commander-in-chief is the Monarch, to whom the chief of the defence staff could appeal: "the chief of the defence staff, if he really did think the prime minister had gone mad, would make quite sure that that order was not obeyed... You have to remember that actually prime ministers give direction, they tell the chief of the defence staff what they want, but it's not prime ministers who actually tell a sailor to press a button in the middle of the Atlantic. The armed forces are loyal, and we live in a democracy, but actually their ultimate authority is the Queen."[63]

The same interview pointed out that while the Prime Minister would have the constitutional authority to fire the Chief of the Defence Staff, he could not appoint a replacement as the position is appointed by the monarch. During the Cold War the Prime Minister was also required to name a senior member of the cabinet as his/her designated-survivor, who would have the authority to order a nuclear response in the event of an attack incapacitating the Prime Minister, and this system was re-adopted after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States.

The programme also addressed the workings of the system; detailing that two persons are required to authenticate each stage of the process before launching, with the submarine captain only able to access the firing trigger after two safes have been opened with keys held by the ship's executive and weapons engineering officers. It was explained that all prime ministers issue hand-written orders, termed the letters of last resort,[64] seen by their eyes only, sealed and stored within the safes of each of the four Royal Navy trident submarines: These notes instruct the captain of what action to take in the event of the United Kingdom being attacked with nuclear weapons that destroy Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom and/or the chain of command. Although the final orders of the Prime Minister are at his or her discretion, and no fixed options exist, four known options are often presented to prime ministers by military advisers when writing such notes of last resort: (i) Captain ordered to respond to the nuclear attack on the UK by launching submarine's nuclear weapons; (ii) Captain ordered not to respond with nuclear weapons; (iii) Captain ordered to use own judgement whether to return fire with nuclear weapons; (iv) Captain ordered to place himself and ship under the command of Her Majesty's Government in Australia, or alternatively of the President of the United States. This system of issuing notes containing orders in the event of the head of government's death is said to be unique to the United Kingdom (although the concept of written last orders, particularly of a ship's captain, is a naval tradition), with other nuclear powers using different procedures. Such orders are destroyed unopened whenever a prime minister leaves office, so the decision of its use or not by previous prime ministers are known only to them - however, all relevant former prime ministers have supported an "independent nuclear deterrent", as does incumbent David Cameron.[65] Only former prime minister Lord Callaghan has given any insight on his orders: Callaghan stated that, although in a situation where nuclear weapon use was required - and thus the whole purpose and value of the weapon as a deterrent had failed - he would have ordered use of nuclear weapons, if needed: ...if we had got to that point, where it was, I felt it was necessary to do it, then I would have done it (used the weapon)...but if I had lived after pressing that button, I could have never forgiven myself.[66]

The process by which a Trident submarine would determine if the British government continues to function includes, amongst other checks, establishing whether BBC Radio 4 continues broadcasting.[67]

The special relationship

Main article: Special relationshipThe 1958 'Agreement For Cooperation on the Uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defence Purposes' also known as the 'Mutual Defence Agreement' was renewed in 1994 and again in 2005.[68]

Cost

The current Trident system cost £12.6bn (at 1996 prices) and costs £280m a year to maintain. Options for replacing Trident range from £5bn for the missiles alone to £20-30bn for missiles, submarines and research facilities. At minimum, for the system to continue safely after around 2020, the missiles will need to be replaced.[69]

Legality

The Government of the United Kingdom has announced plans to renew the UK's only nuclear weapons system, the Trident missile system.[70] They have published a white paper The Future of the United Kingdom’s Nuclear Deterrent in which they state that the renewal is fully compatible with the United Kingdom's treaty commitments and international law.[71] These arguments are summarised in a question and answer briefing published by UK Permanent Representative to the Conference on Disarmament[72]

- Is Trident replacement legal under the Non Proliferation Treaty (NPT)? Renewal of the Trident system is fully consistent with our international obligations, including those on disarmament. ...

- Is retaining the deterrent incompatible with NPT Article VI? The NPT does not establish any timetable for nuclear disarmament. Nor does it prohibit maintenance or renewal of existing capabilities. Renewing the current Trident system is fully consistent with the NPT and with all our international legal obligations. ...

Against

The white paper The Future of the United Kingdom’s Nuclear Deterrent stands in contrast to two counsel's opinions. The first, commissioned by Peacerights,[73] was given on 19 December 2005 by Rabinder Singh QC and Professor Christine Chinkin of Matrix Chambers. It addressed '...whether Trident or a likely replacement to Trident breaches customary international law'[74]

Drawing on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) opinion, Singh and Chinkin advised that:

The use of the Trident system would breach customary international law, in particular because it would infringe the "intransgressible" [principles of international customary law] requirement that a distinction must be drawn between combatants and non-combatants.[74]

The second opinion was commissioned by Greenpeace[75] and given by Philippe Sands QC and Helen Law, also of Matrix Chambers, on 13 November 2006.[76] The opinion addressed

The compatibility with international law, in particular the jus ad bellum, international humanitarian law (‘IHL’) and Article VI of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (‘NPT’), of the current UK strategy on the use of Trident...The compatibility with IHL of deploying the current Trident system...[and] the compatibility with IHL and Article VI NPT of the following options for replacing or upgrading Trident: (a) Enhanced targeting capability; (b) Increased yield flexibility; (c) Renewal of the current capability over a longer period.[77]

With regards to the jus ad bellum, Sands and Law advised that

Given the devastating consequences inherent in the use of the UK’s current nuclear weapons, we are of the view that the proportionality test is unlikely to be met except where there is a threat to the very survival of the state. In our view, the ‘vital interests’ of the UK as defined in the Strategic Defence Review are considerably broader than those whose destruction threaten the survival of the state. The use of nuclear weapons to protect such interests is likely to be disproportionate and therefore unlawful under Article 2(4) of the UN Charter.[78]

The phrase "very survival of the state" is a direct quote from paragraph 97 of the ICJ ruling. With regards to international humanitarian law, they advised that

it [is] hard to envisage any scenario in which the use of Trident, as currently constituted, could be consistent with the IHL prohibitions on indiscriminate attacks and unnecessary suffering. Further, such use would be highly likely to result in a violation of the principle of neutrality.[79]

Finally, with reference to the NPT, Sands and Law advised that

A broadening of the deterrence policy to incorporate prevention of nonnuclear attacks so as to justify replacing or upgrading Trident would appear to be inconsistent with Article VI; b) Attempts to justify Trident upgrade or replacement as an insurance against unascertainable future threats would appear to be inconsistent with Article VI; c) Enhancing the targeting capability or yield flexibility of the Trident system is likely to be inconsistent with Article VI; d) Renewal or replacement of Trident at the same capability is likely to be inconsistent with Article VI; and e) In each case such inconsistency could give rise to a material breach of the NPT.[80]

Government defence

At the start of the House of Commons debate to authorize the replacement of Trident,[81] Margaret Beckett stated:

Article VI of the NPT imposes an obligation on all states: “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a Treaty on general and complete disarmament". The NPT Review Conference held in 2000 agreed, by consensus, 13 practical steps towards nuclear disarmament. The UK remains committed to these steps and is making progress on them. We have been disarming. Since the Cold War ended, we have withdrawn and dismantled our tactical maritime and airborne nuclear capabilities. We have terminated our nuclear capable Lance missiles and artillery. We have the smallest nuclear capability of any recognised nuclear weapon state accounting for less than one per cent of the global inventory. And we are the only nuclear weapon state that relies on a single nuclear system.

The subsequent vote was won overwhelmingly, including unanimous support from the opposition Conservative Party.[82]

The Government position remains that it is abiding by the NPT legally in renewing Trident and Britain has the right to possess nuclear weapons, a position reiterated by Tony Blair in PMQs on 21 February 2007.[83]

In contrast, the report by Sands was commissioned solely by Greenpeace and the report by Singh and Chinkin by the Peace Rights group,[84] both notable groups in opposition to renewal, use or proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Furthermore, the British Government and NATO do not recognise advisory opinion of the ICJ,[85] as interpreter of IHL and referred to by Sands et al., (see Advisory Opinion) with regard to use of nuclear weaponry as legally binding.[86]

This position is held in common with all five nuclear states as defined in the NPT.[citation needed] However, only the United Kingdom has expressed its opposition to the establishment of a new legally binding treaty to prevent the threat or use of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states[87] by its vote in the United Nations General Assembly in 1998.[88]

This legal position is further discussed in the article International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons.

See also

- Anti-nuclear movement in the United Kingdom

- Global Security Institute

- Letters of last resort

- Nuclear disarmament

- Nuclear testing

- The War Game (An earlier, documentary-style, TV film, also dealing with the effects of nuclear attack on the United Kingdom, that was made in 1965 and banned from being broadcast until the mid 1980s)

- Threads (A fictional film about the effects of nuclear war on the United Kingdom)

- United Kingdom and weapons of mass destruction

References

- ^ "UK to be "more open" about nuclear warhead levels". BBC News. 2010-05-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8706600.stm. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ "Federation of American Scientists :: Status of World Nuclear Forces". Fas.org. 2010-05-26. http://www.fas.org/programs/ssp/nukes/nuclearweapons/nukestatus.html. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ (PDF) Prospects for Further Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Special National Intelligence Estimate. CIA. 23 August 1974. p. 40. SNIE 4-1-74. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB240/snie.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ Woolf, Marie (2006-10-29). "So, minister, are we developing new nuclear weapons or not?; Scientists say they are designing a new warhead design, despite government denials". The Independent on Sunday (Newspaper Publishing plc): p. 6.

- ^ "Blair's Trident statement in full". BBC News. 2006-12-04. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/6207584.stm. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ^ Point 64, Strategic Defence Review, Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Defence, George Robertson, July 1998

- ^ SIPRI project on nuclear technology and arms[dead link]

- ^ House of Commons Written Answers, Hansard, 14 July 1998 : Column:171

- ^ Table of Global Nuclear Weapons Stockpiles, 1945-2002, National Resources Defense Council, 25 November 2002

- ^ Ministry of Defence: The United Kingdom’s Future Nuclear Deterrent Capability. National Audit Office. 5 November 2008. ISBN 9780102954364. http://www.nao.org.uk/pn/07-08/07081115.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "UK to be "more open" about nuclear warhead levels". BBC News. 2010-05-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8706600.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ Press Release, Verification Technology Information Centre, 17 August 1995

- ^ Weapons around the world, Jon Wolfsthal, physicsweb, August 2005

- ^ Nuclear Weapons Milestons (Part 1-B), compiled by Wm. Robert Johnston, 3 June 2005

- ^ History of Nuclear Weapons Testing, Greenpeace, April 1996

- ^ Database of nuclear tests, United Kingdom, compiled by Wm. Robert Johnston, last modified 19 June 2005

- ^ Office of the Deputy Administrator for Defense Programs (January 2001). Highly Enriched Uranium: Striking A Balance - A Historical Report On The United States Highly Enriched Uranium Production, Acquisition, And Utilization Activities From 1945 Through September 30, 1996 (Revision 1 (Redacted For Public Release) ed.). U.S. Department of Energy, National Nuclear Security Administration. http://fas.org/sgp/othergov/doe/heu. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ History of the British Nuclear Arsenal, Last changed 30 April 2002

- ^ Public Record Office, London, DEFE 19/180, E66. Declassified Jan 2006 using the FOI Act.

- ^ Inventory of International Nonproliferation Organizations and Regimes, Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

- ^ House of Commons Debate, Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Bill, Hansard, 6 Nov 1997 : Column 455

- ^ Status of CTBT Ratification, British American Security Information Council, last updated on 14 June 2001

- ^ Statement by the Secretary of State for Defence, Hansard 15 Jan 2003 : Column 697

- ^ Royal United Services Institute - Ballistic Missile Defence and the UK April 2005

- ^ a b Possible Nuclear Attack Scenarios on Britain, Paul Rogers, Proceedings of Conference on Nuclear Deterrence: Implications and Policy Options for the 1980s, September 1981

- ^ Protect and Survive, prepared for the Home Office by the Central Office of Information, May 1980

- ^ Britain planned taped messages after nuclear war, by Gregory Katz, Associated Press, 3 October 2008.

- ^ Peter Hennessy, "Cabinets and the Bomb", The British Academy/Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 31.

- ^ Sir M. Perrin, who was present, The Listener, 7 October 1982. Also quoted in How Nuclear Weapons Decisions are Made, p.137, 1986, Oxford Research Group.

- ^ Peter Hennessy, "Cabinets and the Bomb", The British Academy/Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 48.

- ^ Arnold, Lorna (2001).Britain and the H-Bomb: the official history. Published by Palgrave. ISBN 0-333-94742-8 in North America, ISBN 0-312-23518-6 elsewhere. p71

- ^ "Britain's Nuclear Weapons - British Nuclear Testing". Nuclearweaponarchive.org. http://nuclearweaponarchive.org/Uk/UKFacility.html. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ Lorna Arnold, Britain and the H-Bomb, the official history. Published 2001. Palgrave. ISBN 0-333-94742-8 and ISBN 0-312-23518-6 in North America, p65.

- ^ A.J.R.Groom, "British thinking about nuclear weapons", pps 131-154. Published Frances Pinter 1974. ISBN 0-903804-01-8. (Note that this is an old 10 digit ISBN, as used at publication in 1974)

- ^ Lorna Arnold p147, ibid

- ^ Amazon.co.uk review, The Impact of Polaris: The Origins of Britain's Seaborne Nuclear Deterrent, J.E. Moore.

- ^ Norris, Robert S. , William M. Arkin, Hans M. Kristensen, and Joshua Handler ,"British nuclear forces, 2001", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists , vol. 57, no. 06, pp. 78-79. ISSN 0096-3402 doi:10.2968/057006025 (November/December 2001)

- ^ "Britain's Next Nuclear Era". Federation of American Scientists. December 7, 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-02-06. http://web.archive.org/web/20070206035127/http://www.fas.org/blog/ssp/2006/12/britains_next_nuclear_era_1.php. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ "Stockpile Stewardship Plan: Second Annual Update (FY 1999)" (PDF). US Department of Energy. April 1998. http://www.fas.org/blog/ssp/images/W76req.pdf. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ "RAF nuclear frontline Order-of-Battle 1966-94". http://nuclear-weapons.info/images/RAF-nuclear-frontline-Order-of-Battle-1966-94.PNG. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ Nuclear Weapons - Mr. Hanley, Hansard, 22 June 1993 : Column 154

- ^ Operational Selection Policy OSP 11, Nuclear Weapons Policy 1967-1998, The National Archives, November 2005

- ^ Lord Garden, Lords Hansard, 24 Jan 2007 : Column 1179

- ^ Lance Chronology, Redstone Arsenal Historical Information

- ^ P G Barry (October 2001). Deployment of Lance, 50th Missile Regiment Royal Artillery. Royal Artillery. http://www.50missileclubra.com/lance.html. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ Honest John. Windscreen, Military Vehicle Trust. Summer 2006. http://www.50missileclubra.com/honestjohn.html. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ Norris, Burrows, Fieldhouse. Nuclear Weapons Databook Vol 5. British, French and Chinese Nuclear Weapons, p63. Published Westview Press, Oxford, 1994. ISBN 0-8133-1611-1

- ^ John Clearwater (1998). Canadian Nuclear Weapons: The Untold Story of Canada's Cold War Arsenal. Dundurn Press Ltd. p. 284. ISBN 1550022997. http://books.google.com/?id=5-R7EJ0r680C. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ Hans M. Kristensen (February 1978). History of the Custody and Deployment of Nuclear Weapons: July 1945 through September 1977. US Department of Defence. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/news/19991020/04-51.htm. Retrieved 2006-05-23.

- ^ Hans M. Kristensen (February 2005) (PDF). U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe. Natural Resources Defense Council. http://www.nrdc.org/nuclear/euro/euro.pdf. Retrieved 2006-05-23.

- ^ How Nuclear Weapons Decisions are Made, Scilla McClean (ed), Oxford Research Group, 1984, [ISBN 0-333-40583-8], p. 120

- ^ Cocroft, Wayne D. (2000). Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture. Swindon; English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-718-0.

- ^ PRO, London, DEFE 25/335, E93 classified until 2010, obtained Jan 2006 using the FOI Act.

- ^ PRO, London, T225/3280, E32.

- ^ Kate Pyne, The AWRE Contribution to Chevaline. Proceedings of the Royal Aeronautical Society Symposium on Chevaline, 2004. Published 2005 as ISBN 1-85768-109-6

- ^ PRO, London, DEFE 25/335, E44 Annex A, 'Unacceptable Damage', plus maps. Classified until 2010, and obtained Jan 2006 using the FOI Act.

- ^ British Nuclear Doctrine: The 'Moscow Criterion' and the Polaris Improvement Programme, John Baylis, Contemporary British History, Vol. 19, No. 1, Spring 2005, pp.53-65

- ^ http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyes/65F3D7AC-4340-4119-93A2-20825848E50E/0/sdr1998_complete.pdf

- ^ http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyre/65F3D7AC-4340-4119-93A2-20825848E/0?sdr1998_complete.pdf

- ^ Ministry of Defence (UK) (15 November 2007). "Nuclear weapons security - MoD statement". BBC Newsnight. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/newsnight/7097121.stm. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ British nuclear weapon control (streaming video), Susan Watts, BBC Newsnight, November 2007

- ^ "BBC press release November 2007". Bbc.co.uk. 2007-11-15. http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2007/11_november/15/newsnight.shtml. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ "Whose hand is on the button?". BBC News. 2 December 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/7758314.stm. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Ron (January 2009). "The Letter of Last Resort". Slate Magazine. http://www.slate.com/id/2208219/pagenum/all. Retrieved 2009-05-18. "In the control room of the sub, the Daily Mail reports, "there is a safe attached to a control room floor. Inside that, there is an inner safe. And inside that sits a letter. It is addressed to the submarine commander and it is from the Prime Minister."

- ^ "Brown backs Trident replacement". BBC News. 21 June 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/5103764.stm. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Finger on the nuclear button". BBC News. 2 December 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_7758000/7758347.stm. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Peter Hennessy. The Secret State: Whitehall and the Cold War, 1945-1970. Allen Lane, The Penguin Press. 256 pages. ISBN 0-713-99626-9

- ^ US-UK nuclear weapons collaboration under the Mutual Defence Agreement, Nigel Chamberlain, Nicola Butler and Dave Andrews, British American Security Council, June 2004

- ^ "Trident: the done deal". New Statesman. http://www.newstatesman.com/Economy/200506130008. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ Memoranda on the Future of the UK's Strategic Nuclear Deterent: the White Paper to the House of Commons Defence Committee

- ^ The Future of the United Kingdom’s Nuclear Deterrent(pdf) December 2006:

- ^ Britain's Nuclear Deterrent by UK Permanent Representative to the Conference on Disarmament

- ^ Peacerights Memorandum from Peacerights

- ^ a b Singh, Rabinder; and Chinkin, Christine; The Maintenance and Possible Replacement of the Trident Nuclear Missile System Introduction and Summary of Advice for Peacerights (paragraph 1 and 2)

- ^ Greenpeace Trident replacement may be illegal under international law

- ^ Sands, Philippe; and Law, Helen; The United Kingdom's nuclear deterrent:Current and future issies of legality (see References)

- ^ Sands, Philippe; and Law, Helen; References, paragraph 1

- ^ Sands, Philippe; and Law, Helen; References, paragraph 4(i)

- ^ Sands, Philippe; and Law, Helen; References, paragraph 4(iii)

- ^ Sands, Philippe; and Law, Helen; References, paragraph 4(iv)

- ^ "Trident". Hansard. 14 March 2007. http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2007-03-14c.298.0.

- ^ "Trident plan wins Commons support". BBC NEWS. 15 March 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/6448173.stm.

- ^ "Blair wins Trident vote after telling UK Parliament that the NPT gives Britain the Right to have nuclear weapons". Disarmament Diplomacy. Spring 2007. http://www.acronym.org.uk/dd/dd84/84news01.htm.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard (20 December 2005). "Use of Trident 'would be illegal'". London: The Guardian. http://politics.guardian.co.uk/homeaffairs/story/0,11026,1671191,00.html.

- ^ "Legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons". International Court of Justice. 8 July 1996. http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/95/7495.pdf?PHPSESSID=9272f93615543b6fc6d7703ca7b34811.

- ^ "Q&A: Nuclear disarmament". BBC NEWS. 11 December 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/6103398.stm.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Resolution 77 session 53 Operative Paragraph 17, Resolution Y page 42

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Verbotim Report meeting 79 session 53 page 27 on 4 December 1998 (retrieved 2008-03-11)

Further reading

- Arnold, Lorna (2001). Britain and the H-Bomb. The official history up to the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement. Copyright MoD. Published Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-23518-6 in North America, ISBN 0-333-94742-8 outside North America.

- Gowing, Margaret and Arnold, Lorna (1974). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945-1952. Volume 1: Policy Making. London: The Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-15781-8.

- Gowing, Margaret and Arnold, Lorna (1974). Independence and Deterrence: Britain and Atomic Energy, 1945-1952. Volume 2: Policy Execution. London: The Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-16695-7.

- Denys Blakeway and Sue Lloyd-Roberts (1985). Fields of Thunder: Testing Britain's Bomb London, Unwin.

- Wynne, Humphrey (1997). RAF Strategic Nuclear Deterrent Forces, their origins, roles and deployment, 1946-69. The documentary history. Copyright MoD. Published by The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-772833-0.

- Paul Rogers, "Possible Nuclear Attack Scenarios on Britain", Proceedings of the Conference on Nuclear Deterrence, Implications and Policy Options for the 1980s, International Standing Conference on Conflict and Peace Studies, London, 1982.

- Roy Dommett, "The Blue Streak Weapon". Prospero, refereed journal of the BROHP, Spring 2005.

- George Hicks and Roy Dommet, "History of the RAE [Farnborough] and Nuclear Weapons". Prospero, refereed journal of the BROHP, Spring 2005.

- Proceedings of the Royal Aeronautical Society, Symposium on Chevaline 2004, ISBN 1-85768-109-6. See note on sources at Talk:Nuclear weapons and the United Kingdom

- Dr Peter Jones, Director AWE (Ret), "The Chevaline Technical Programme". Prospero, the refereed journal of the BROHP, Spring 2005.

- Peter Nailor, The Nassau Connection: the organisation and management of the British POLARIS project, London: H.M.S.O, (1988).

- Dr Frank Panton, "The Unveiling of Chevaline". Prospero, the refereed journal of the BROHP, Spring 2005.

- Dr Frank Panton, "Polaris Improvements and the Chevaline Programme". Prospero, the refereed journal of the BROHP, Spring 2004.

External links

- Video archive of the UK's Nuclear Testing at sonicbomb.com

- British Nuclear Policy, BASIC

- Table of UK Nuclear Weapons models

- Trident: the done deal, Robert Fox, New Statesman, 13 June 2005

- Text of the Nuclear Explosions (Prohibition and Inspections) Act 1998

- Nuclear Notebook: British nuclear forces, 2001, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Nov/Dec 2001.

- The United Kingdom's Defence Nuclear Programme, UK Ministry of Defence, 4 September 2001

- British Nuclear Forces, 2005, by Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 2005.

- Britain's secret nuclear blueprint The Sunday Times, 12 March 2006

- Revealed: UK develops secret nuclear warhead by Michael Smith, The Sunday Times, 12 March 2006

- Government White Paper Cm 6994 The Future of the United Kingdom’s Nuclear Deterrent (December 2006)

- Richard Moore (March 2004) (PDF). The Real Meaning of the Words: a Pedantic Glossary of British Nuclear Weapons. Mountbatten Centre for International Studies, University of Southampton. http://www.mcis.soton.ac.uk/Site_Files/pdf/nuclear_history/Working_Paper_No_1.pdf.

- http://www.nuclear-weapons.info/

- Annotated bibliography for the British nuclear weapons program from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

Categories:- Nuclear history of the United Kingdom

- Nuclear weapons programme of the United Kingdom

- Nuclear weapons

- Nuclear weapons policy

- Nuclear proliferation

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.