- Italian irredentism in Nice

-

Giuseppe Garibaldi, the most renowned Nizzardo Italian

Giuseppe Garibaldi, the most renowned Nizzardo Italian

Italian irredentism in Nice was the political movement supporting the annexation of Nice to the Kingdom of Italy. The term was coined by Italian Irredentists who sought the unification of all Italian peoples within the Kingdom of Italy. Italian and Ligurian speaking populations of the County of Nice (Nizza) formed the majority of the county's population until the mid-19th century.[1] During the Risorgimento, in 1860, the Savoy government allowed France to annex the region of Nice from the Kingdom of Sardinia in exchange for French support of its quest to unify Italy. Consequently, the Nizzardo Italians were shunned from the Italian unification movement and the region has since become primarily French-speaking.

Contents

History

The Contea di Nizza (as the area of Nice had been called since medieval times) was populated by Ligurian tribes up to the occupation by the Romans. These tribes were conquered by Augustus and were fully romanized (according to Theodore Mommsen) by the fourth century, when the barbarian invasions began.

The Franks conquered the region after the fall of Rome, and the local Romance language speaking populations became integrated within the County of Provence, with a period of independence as a maritime republic (1108–1176). In 1388, the commune of Nice fell under the protection of the Duchy of Savoy, and Nice continued to be controlled, directly or indirectly, by Savoy right up until 1860.

During this time, the maritime strength of Nice rapidly increased until it was able to cope with the Barbary pirates. Fortifications were largely extended by the rulers of Savoy and the roads of the city and surrounding region improved. Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, abolished the use of Latin and established the Italian language as the official language of Nice in 1561.[2]

Conquered in 1792 by the armies of the First French Republic, the County of Nice was part of France until 1814; but after that year it was placed under the protection of the Kingdom of Sardinia by the Congress of Vienna.

By a treaty concluded in 1860 between the Sardinian king and Napoleon III, the County of Nice was again ceded to France, along with Savoy, as a territorial reward for French assistance in the Second Italian War of Independence against Austria, which saw Lombardy unified with Piedmont-Sardinia.

Giuseppe Garibaldi, born in Nice, strongly opposed the cession to France, arguing that the plebiscite that ratified the treaty was not "universal" and contained irregularities. He was elected at the "French National Assembly" for Nice with 70% of the votes in 1871, and quickly promoted the withdrawal of France from Nice, but the elections were invalidated by the French authorities.[3]

In 1871/72 there were popular riots in the city (called by Garibaldi Vespri Nizzardi[4]), promoted by the "Garibaldini" in favour of unification with the Kingdom of Italy.[5] Fifteen Nizzardo Italians were processed and condemned for these riots, supported by the 'Nizzardo Republican Party'[6]

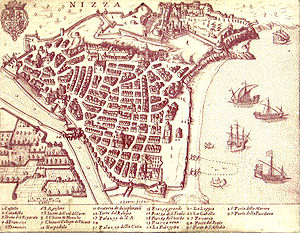

Nice in 1624, when it was called Nizza

Nice in 1624, when it was called Nizza

More than 11,000 Nizzardo Italians refused to be French and moved to Italy (mainly Turin and Genoa) after 1861. The French government closed the Italian language newspapers Diritto di Nizza and Voce di Nizza in 1861, and Il Pensiero di Nizza in 1895. In these newspapers wrote the most famous writers in Italian language of Nice: Giuseppe Bres, Enrico Sappia, Giuseppe André.

One of the most renowned Nizzardo Italians was Luciano Mereu, a follower of Garibaldi. On November 1870 he was temporarily exiled from Nice together with the "garibaldini" Adriano Gilli, Carlo Perino and Alberto Cougnet.[7] Later, Luciano Mereu was elected in 1871 as counselor of Nizza under Mayor Augusto Raynaud (1871–1876) and was member of the Commissione garibaldina di Nizza with Donato Rasteu, its President until 1885.

Italian irredentists long considered the annexation of Nice to be one of their main targets. In 1942, during the Second World War, the former County of Nice was occupied and administered by Italy until 1943.

The Italian occupation of France was far less severe than the German. Therefore thousands of Jews (some speaking Italian) took refuge there. For a while the city became an important centre for various Jewish organizations, especially after the landing of the Allies in North Africa (November 1942). However, when the Italians signed the armistice with the Allies, German troops invaded the former Italian zone (Sept. 8, 1943) and initiated brutal raids. Alois Brunner, the SS official for Jewish affairs, was placed at the head of units formed to search out Jews. Within five months, 5,000 Jews were caught and deported.[8]

The area was returned to France following the war and in 1947, the areas of La Brigue and Tende, which had remained Italian after 1860 were ceded to France. Thereafter, a quarter of the Nizzardo Italians living in that mountainous area moved to Piedmont and Liguria in Italy (mainly from Val di Roia and Tenda).[9]

Today, after a sustained process of Francization conducted since 1861, the former county is predominantly French-speaking. Only along the coast around Menton and in the mountains around Tende there are still some native Italian speakers of the original Intemelio ligurian dialect.[10]

Currently the area is part of the Alpes-Maritimes department of France.

Language

In Nice the language of Church, Municipality, Law, School, Theatre was always the Italian language....From 460 AD to mid XIX century the County of Nice counted 269 writers, not including the still living. Of these 269 writers, 90 used Italian, 69 Latin, 45 Italian and Latin, 7 Italian and French, 6 Italian with Latin and French, 2 Italian with Nizzardo dialect and French, 2 Italian and Provençal.[11]Augustus conquered the Nizzardo, populated by Ligures, and left a monument (Trophy of the Alps) with the names of the Ligurian tribes: these names are the first evidence of the Italic language spoken in the County of Nice. The Ligurians were fully Romanized in the following centuries and their Latin language became an Italic, Western Romance language during the Middle Ages.

A map of the County of Nice (Nizza in Italian) showing the area of the Kingdom of Sardinia and annexed in 1860 to France (light brown) and to Italy (yellow)

Before the year 1000 the area of Nice was part of the Ligurian League, under the Republic of Genoa, and the population spoke the dialect common to western Liguria that today is called Intemelio[12] . The medieval writer Dante Alighieri wrote, in his Divine Comedy, that the river Var, near Nice, was the western limit of the Italian Liguria.

Around the twelfth century Nice came under the French House of Anjou, who favoured the immigration of peasants from Provence who brought their Occitan language.[13] In those years, the people of the mountainous areas of the upper Var valley started to lose their Ligurian linguistic characteristics and began to adopt Provençal influences. From 1388 to 1860 the County of Nice was under the Savoyard rule and remained connected to the Italian dialects and peninsula. In those centuries the local dialect of Nice, known as Niçard, was similar to Monégasque (of the Principality of Monaco) but with more Occitan influences.

Most scholars today classify Niçard as a dialect of Occitan and Monégasque as a dialect of Ligurian, but Sue Wright wrote that, prior to when the Kingdom of Sardinia ceded the County of Nice to France, Nice was not French-speaking before the annexation but underwent a shift to French in a short space of time...and is surprising that the local Italian dialect, the Nissart, disappeared quickly from the private domain". [14]

She also wrote that one of the main reasons of the disappearance of the Italian language in the County was because "(m)any of the administrative class under Piedmont-Savoy ruler, the soldiers, jurists, civil servants and professionals who used Italian in their working lives, moved after annexation to Piedmont. Their places and roles were taken by incomers from France".

Indeed, immediately after 1861, the French government closed all the newspapers in Italian and more than 11,000 Nizzardo Italians moved to the Kingdom of Italy. The dimension of the "exodus" can be deducted by the fact that in the Savoy census of 1858, Nice had only 44,000 inhabitants. In 1881 the New York Times wrote that before the French annexation the Nizzards were quite as much Italians as the Genoese, and their dialect was, if anything, nearer the Tuscan than is the harsh dialect of Genoa.[15]

In twenty years the Nizzardo Italians were reduced to a small minority and even Niçard was increasingly assimilated by Occitan, with many French loanwords. (Modern-day linguists usually hold that Niçard is an Occitan dialect.)[16]

Giuseppe Garibaldi defined his "Nizzardo" as an Italian dialect, albeit with strong similarities to Occitan and with some French influences, and for this reason promoted the union of Nice to the Kingdom of Italy.

Even today some scholars (like the German Werner Forner, the French Jean-Philippe Dalbera and the Italian Giulia Petracco Sicardi) agree that the Niçard has some characteristics (phonetical, lexical and morphological) that are typical of the western Ligurian language. The French scholar Bernard Cerquiglini pinpoints in his Les langues de France the actual existence of a Ligurian minority in Tende, Roquebrune and Menton, a remnant of a bigger mediaeval "Ligurian" area that included Nice and most of the coastal County of Nice.

Another reduction in the number of the Nizzardo Italians happened after World War II, when the defeated Italy was forced to surrender to France the small mountainous area of the County of Nice that had retained in 1860. From the Val di Roia, Tenda and Briga one quarter of the local population moved to Italy in 1947.

In the century of nationalism between 1850 and 1950, the Nizzardo Italians were reduced from the 70% majority [17] of the 125,000 living in the County of Nice at the time of the French annexation to the actual minority of nearly two thousand (in the area of Tende and Menton) today.

Nowadays, Nizzardo Italians are fluent in French, but a few of them still speak the original Ligurian-influenced language of Nissa La Bella.

See also

- Italia irredenta

- Giuseppe Garibaldi

- Monegasque

- Mentonasque

- Intemelio

- Ligurian language

- Italian irredentism in Corsica

- Italian occupation of France during World War II

References

- ^ Amicucci, Ermanno. Nizza e l’Italia. p 64

- ^ Amicucci, Ermanno. Nizza e l’Italia. Introduction

- ^ The Times on the 1871 riots in Nice

- ^ "Vespri Nizzardi" (in Italian) in Nizza, negli ultimi quattro anni of Giuseppe André

- ^ Stuart, J. Woolf. Il risorgimento italiano p.44

- ^ André, G. Nizza, negli ultimi quattro anni (1875) p. 334-335

- ^ Letter of Alberto Cougnet to Giuseppe Garibaldi, Genova, 7 dicembre 1867,"Archivio Garibaldi", Milano, C 2582)

- ^ Italians and Jews in Nice 1942/43

- ^ Intemelion

- ^ Intemelion 2007

- ^ Fancesco Barberis: "Nizza Italiana" p.51

- ^ Werner Forner.À propos du ligurien intémélien - La côte, l'arrière-pays, Travaux du Cercle linguistique de Nice, 7-8, 1986, pp. 29-62.

- ^ Gray, Ezio. Le terre nostre ritornano... Malta, Corsica, Nizza. Chapter 2

- ^ Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe

- ^ http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9800E5DE133CEE3ABC4151DFB566838A699FDE&oref=slogin New York Times, 1881

- ^ Bec, Pierre. La Langue Occitane. pag 58

- ^ Amicucci, Ermanno. Nizza e l’Italia. pag 126

Bibliography

- André, Giuseppe. Nizza, negli ultimi quattro anni. Editore Gilletta. Nizza, 1875

- Amicucci, Ermanno. Nizza e l’Italia. Ed. Mondadori. Milano, 1939.

- Barelli Hervé, Rocca Roger. Histoire de l'identité niçoise. Serre. Nice, 1995. ISBN 2-84410-223-4

- Barberis, Francesco. Nizza italiana: raccolta di varie poesie italiane e nizzarde, corredate di note. Editore Tip. Sborgi e Guarnieri (Nizza, 1871). University of California, 2007

- Bec, Pierre. La Langue Occitane. Presses Universitaires de France. Paris, 1963

- Gray, Ezio. Le terre nostre ritornano... Malta, Corsica, Nizza. De Agostini Editoriale. Novara, 1943

- Holt, Edgar. The Making of Italy 1815–1870, Atheneum. New York, 1971

- Stuart, J. Woolf. Il risorgimento italiano. Einaudi. Torino, 1981

- Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, Centre Histoire du droit. Les Alpes Maritimes et la frontière 1860 à nos jours. Actes du colloque de Nice (1990). Ed. Serre. Nice,1992

- Werner Forner. L’intemelia linguistica, ([1] Intemelion I). Genoa, 1995.

External links

- (Italian) Nice and Italian Irredentism

- (French) Map of the Languages of France, with reference to the Niçard and Genoese

- (Italian) Magazine about Briga and Tenda

- (Italian) Fancesco Barberis: "Nizza Italiana" (Google Book)

Italian irredentism by region

Italian diaspora By Country AfricaAmericasAsiaIndia · Lebanon · Turkey · United Arab EmiratesEuropeOceania

See also 1 former Italian colonies and protectorates Categories:- Italian people

- Italian irredentism

- Political history of France

- Ligurian language (Romance)

- History of Nice

- History of Italy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.