- Death and the King's Horseman

-

Death and the King's Horseman Written by Wole Soyinka Characters Elesin

Olunde

Iyaloja

Simon Pilkings

Jane Pilkings

AmusaDate premiered March 1, 1975 Place premiered Vivian Beaumont Theatre Original language English Setting Nigeria, 1944 Death and The King's Horseman is a play by Wole Soyinka based on a real incident that took place in Nigeria during British colonial rule: the ritual suicide of the horseman of an important chief was prevented by the intervention of the colonial authorities.[1] In addition to the British intervention, Soyinka calls the horseman's own conviction toward suicide into question, posing a problem that throws off the community's balance.

Contents

Plot

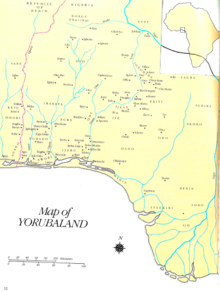

Death and The King's Horseman builds upon the true story to focus on the character of Elesin, the King's Horseman of the title. According to a Yoruba tradition, the death of a chief must be followed by the ritual suicide of the chief's horseman, because the horseman's spirit is essential to helping the chief's spirit ascend to the afterlife. Otherwise, the chief's spirit will wander the earth and bring harm to the Yoruba people. The first half of the play documents the process of this ritual, with the potent, life-loving figure Elesin living out his final day in celebration before the ritual process begins. At the last minute the local British colonial ruler, Simon Pilkings, intervenes, the suicide being viewed as barbaric and illegal by the British authorities.

In the play, the result for the community is catastrophic, as the breaking of the ritual means the disruption of the cosmic order of the universe and thus the well-being and future of the collectivity is in doubt. As the action unfolds the community blames Elesin as much as Pilkings, accusing him of being too attached to the earth to fulfill his spiritual obligations. Events lead to tragedy when Elesin's son, Olunde, who has returned to Nigeria from studying medicine in Europe, takes on the responsibility of his father and commits ritual suicide in his place so as to restore the honour of his family and the order of the universe. Consequently, Elesin kills himself, condemning his soul to a degraded existence in the next world. In addition, the dialogue of the native suggests that this may have been insufficient and that the world is now "adrift in the void".

Another Nigerian playwright, Duro Ladipo, had already written a play in the Yoruba language based on this incident, called Oba waja (The King is Dead).[2]

Yoruba Perception of the World Around Them

See also: Yoruba religion

The way in which the Yoruba peoples view the world must be understood before Death and the King’s Horseman can be accurately interpreted. Yoruba culture has several key ideas that are presented using language, imagery, and different behaviors. Thinking like a Yoruba individual requires that these three mediums be experienced, internalized and visualized within the “mind’s eye”.[4] When one experiences any one of these methods of expression, what is perceived within the mind, namely the iran (“mental image”) becomes closely linked to the perceiver's oju inu (“inner eye” or “insight”).[5] Experiencing words, images, and behaviors, the Yoruba believe, results in the interaction of two key Yoruba concepts, that of the iran and of the oju inu, the interaction of which is like a fusion—when the iran is perceived by the oju inu, it is as if that image remains with its perceiver. To put it into more Western terminology, it would be like saying, each event one experiences teaches a small lesson that will remain within the soul of the one who learned it forever.

The Two Worlds: Aye and Orun

The Yoruba believe that the world we live in is split into two parallel realms that are closely intertwined. The aye is the tangible, visible world that all sentient beings experience everyday; the orun is the spiritual invisible realm inhabited by: Gods, ancestors and spirits. This is often represented and conceptualized as a flat, circular divination tray, with a raised, fancifully engraved border. Often, the pictures and images along the circumference of the tray represent mythological events, people or can simply be related to quotidian events and affairs—the main take away is the symbolism of a complex world full of forces that are constantly interacting and competing with one another. Further, at the outset of a divination (the act of seeking knowledge of the future or the unknown via supernatural means) a diviner will inscribe intersecting lines on the flat surface of the divination tray. Such lines are referred to as orita meta, literally “the point of intersection between [both] cosmic realms.[6]” These lines are always drawn at the beginning of the divination ritual in order to open up spiritual channels of communication before the diviner can reveal the meaning of the lines.

The Orun: The World of the Spirits, Gods and Ancestors

Oludumare (a.k.a. Odumare, Olorun, Eleda and Eleemi) would be the equivalent of God in Christianity. Oludumare is thus believed to be the creator of all things in existence. However, there is not a gender attached to this deity and it maintains a strictly laissez-faire relationship with respect to both human and divine affairs. More importantly, Oludumare is the source of each sentient beings’ ase, or life force.[6]

The orisa, namely the “deified ancestors and/or personified natural forces” fall into two categories.[4] They are either of the orisa funfun, the “cool, temperate and symbolically white” or of the orisa gbigbona, the “hot, temperamental gods.[4]" Those gods belonging to the orisa funfun are usually mild mannered, calm, “soothing, reflective” and consist of the following divinities [4]:

- Obatala/Orisanla: the divine sculptor

- Osoosi/Eyinle: hunter and water lord

- Osanyin: lord of leaves and medicines

- Oduduwa: first monarch at Ile-Ife, the cradle of the Yoruba civilization

- Yemoja, Osun, Yewa and Oba: queens of their respective rivers [8]

Many of the orisa gbigbona tend to be male, however, not all of them. They themselves include:- Ogun: god of iron

- Sango: former king of Oyo and lord of thunder

- Obaluaye: lord of pestilence

- Oya: Sango’s wife and queen of the whirlwind [9]

The division of the orisa has nothing to do with good and evil; rather, just as humans are believed to contain both good and bad attributes, the orisa themselves are viewed in this light. Even more interesting, the Yoruba pantheon is not a hierarchy. Therefore Oludumare, although creator of all things is not viewed as the King of orun in an absolutist sense; instead, the importance attached to any given orisa is more a reflection of their popularity in a given region.All deities contained within the Yoruba pantheon are believed to periodically enter the aye, and thus can interact and provide guidance, or interfere maliciously in human affairs. However, two important deities, Ifa and Esu/Elegba, are essentially the gatekeepers between orun and aye. Ifa, “actually a Yoruba system of divination, is presided over by Orunmila, its mythic founder” who also sometimes may be referred to as Ifa.[9] Esu/Elegba “is the divine messenger and activator.[9]” It is a central belief of the Yoruba people that Ifa provides them a means by which to understand the forces that influence their lives on a daily basis; this can be achieved in a variety of ways, most notably sacrifice and prayer. A diviner, known as babalawo, literally “father of ancient wisdom” will use a variety of methods to communicate with the inhabitants of orun, or to identify the “enemies of humankind,” namely: “Death, Disease, Infirmity, and Loss.[9]” The babalawo may also identify other entities for concern: egbe abiku literally “spirit children” that kill newborn babies, or aje and oso, literally “witches” and “wizards” respectively.[9] In contrast to Ifa, a being that can be identified, communicated and reasoned with, Esu/Elegba, is unpredictable. Esu is the keeper of all the sacrifices to orun and the enforcer of all ritual processes. If not properly acknowledged and worshipped, a common Yoruba expression warns, “life is the bailing of waters with a sieve.[9]”

Egungun masked dancers. They are believed to be able to communicate with ancestors by the Yoruba. [10]The ancestors, collectively known as “oku orun, osi, babanla and iyanla” are the other major group inhabiting orun.[9] Although they are no longer living in the realm of the living, they are not viewed as being deceased, as in Christianity. They can still be communicated with and are an important source of guidance within Yoruba culture. This can be achieved in one of two ways: (i) via masked diviners known as the egungun or (ii) or by speaking with living relatives who are often believed to be partial reincarnations of departed ancestors. As an example, consider a female child that a diviner realizes is an incarnation of her departed grandmother. She would be named Yetunde, literally “Mother-has-returned”—the grandmother is believed to remain in orun but part of her, her emi literally “spirit” or “breath” will reside within the child.[9]

Aye: The Tangible World

A good definition of aye is the world in which all sentient beings reside. However, this misses a key concept, namely that it is take as a given in Yoruba culture that the residents of orun regularly interact with the living. Thus, the aye also includes these interactions and at times can even contain, at different points in time, members of orun. The Yoruba saying, “Aye l’oja, orun n’ile" best capture this idea and it means, “The world is a marketplace we [all] visit, [and] the otherworld is home.[9]” Thus, the Yoruba believe that we all exist forever in the orun once we arrive there. The Yoruba also believe that human life is unpredictable and fleeting; another common saying, “Aye l’ajo, orun n’ile” meaning “The world [life] is a journey, the other world [afterlife] is home.[11]” During one's stay in aye, the Yoruba believe that one should strive to achieve: “long life, peace, prosperity, progeny, and good reputation.[11]” These are best achieved through seeking to obtain: “wisdom, knowledge” and “understanding.[11]”

From the standpoint of social organization and hierarchy, the Yoruba are very open, yet they still possess a monarchy and much social stratification. Just as in the orun there is no supreme ruler who dictates public policy; rather policy decisions are made between everyone willing to participate. Similar to the United States, there exists a system of checks-and-balances in order to ensure a fairly equal society. The reason that the Yoruba strive for equality stems from their belief system. Recall that each person is believed to possess an ase, or life force, given to them by Oludumare. Thus, each person is believed to be inherently equal and ranks exist because a person has striven to obtain “wisdom, knowledge” and “understanding” and has risen to their rank via their own merit.

Ogun: A closer look

As previously mentioned, Ifa, god of divination and Esu, the god who is responsible for carrying offerings unto the Yoruba pantheon inhabiting orun as well as protecting traditional rituals are "widely known and worshiped as Ogun.[12]" To get a sense of how important Ogun is in Yoruba culture, it is logical to explore the extent to which he was worshipped, since this is a direct measure of his significance. "Ogun" counts for "14 percent of all orisa reported" throughout Oyo.[13] He is third only to Ifa and Esu who account for 19 and 17 percent of orisa reported.[13] Further, when one considers the fact that the aforementioned deities are often collectively worshipped as Ogun it becomes even clearer that Ogun is a significant deity within the Yoruba pantheon.

Even more is revealed about Ogun when one analyzes the traditional Yoruba chants about him:

-

- On the days when Ogun is angered,

- There is always disaster in the world.

- The world is full of dead people going to heaven.

- The eyelashes are full of water.

- Tears stream down the face.

- A bludgeoning by Ogun causes a man's downfall.

- I see and hear, I fear and respect my orisa.

- I have seen your [bloody] merriment.[14]

Ogun is considered one of the most powerful deities but on a more fundamental level, he represents the duplicity of man. Ogun is endowed with many contradictory traits. He is either "fiery or cool," or can represent both "death and healing.[15]" Further, he is often begged for mercy or forgiveness:

-

- Ogun, here is your festival dog.

- Do us no harm.

- Keep us safe from death.

- Do not let the young have accidents

- * * * * * * *

- Let us have peace.[16]

Soyinka was deeply influenced by Ogun, "The philosophy that undergirds [Soyinka's] writings is derived as much from the legends of Ogun, the Yoruba god of war and creativity, as from the works of Nietzsche, the modern philosopher of antitradition [sic] and rebellion.[17]"

Ogun's many contradictory personality traits come out as a major theme within the novel, namely the duplicity of man and nature, which is exemplified in the struggle of the native Africans to carry out their ritual, while the British try as they might to stop them. Further, the intervention of the British into matters about which they understand little has unintended consequences; Olunde, the eldest of the horseman's sons, commits suicide in order to fulfill his father's obligation in the uncompleted ritual. This is an exact incarnation of Esu and Ogun within the play; they have literally entered aye and influenced the chain of human events, ensuring that the ritual was successfully performed and since Elesin was not complicit, they took away his son from him as punishment. This punishment ultimately drove him to commit suicide in shackles at the play's dramatic end.

Themes and Motifs

- Duty[1]

- Anti-colonialism is considered a theme by some scholars based on aspects of the text, but Soyinka specifically calls the colonial factors "an incident, a catalytic incident merely" in the "Author's Note" prepended to the play.

Human Understanding of Life and Death

In the play, the underlying theme of understanding shows how all humans struggle to comprehend each other, life and death. First, the theme of understanding is explored through the English colonists and their cultural tension with the native Yoruba people. In the Second Act, the District Officer, Pilkings, and his wife, Jane, first confront the theme of understanding when they dress up for a ball wearing native death costumes. They see no problem with it, but Mr. Pilkings’ employee, Amusa, a native policeman, is frightened by them wearing the costumes, believing it to be bad for people to touch this cloth of death. Although this situation could be looked at on the surface as "clash of cultures," a deeper conflict, involving understanding and respect relating to each other and to death, is also present.

Later in the play, Jane, who is still wearing the costume, meets with Elesin’s European educated son, Olunde who tells her that he has “discovered that you have no respect for what you do not understand". Jane is angry with his view, but they continue to visit. Olunde is frustrated at her inability to try to understand or at least to respect that someone else might have a different view of death from her own. While this scene seems well suited to a "clash of cultures" interpretation, it can also be seen as an examination of the basic human understanding of death, and the roadblocks humans encounter—both cultural (in Jane’s case) and spiritual (in the case of Elesin and the natives). The reader is shown that it is almost impossible for Jane, as a human, to understand and respect these ideas which she has been conditioned against.

At the end of the story, when Pilkings is talking with Elesin in the cell, the theme of understanding is once more brought out. "You don’t quite understand it all but you know that tonight is when what ought to be must be brought about," Elesin tells Pilkings. In this sentence, Elesin alludes to both his death ritual and the cultural gap, uniting the threnodic and cultural themes into one of understanding. Finally, Olunde, talking with Pilkings—who he thinks has just come from witnessing Elesin’s death—sums up a main aspect of the theme of understanding which relates to both cultural differences and death, saying, "you must know by now there are things you cannot understand—or help".

The play is not completely just a struggle of understanding for the colonists. The larger struggle is inside the minds of Elesin and the Yoruba people as they try to understand death and the transition into death. In the first scene, this is especially apparent as Elesin prepares for death and the Praise-singer spouts a flood of questions aimed at finding answers to the mystery of death. "There is only one world to the spirit of our race," the Praise-singer says. "If that world leaves its course and smashes on boulders of the great void, whose world will give us shelter?" Here he is trying to gain understanding about what would happen if Elesin isn’t successful in carrying out his death ritual. He struggles to know what their fate would be. Later, as Elesin is further into his transition into death, the Praise-singer asks him questions about what he is experiencing, hoping to gain an understanding. "Is there now a streak of light at the end of the passage, a light I dare not look upon?" he asks. "Does it reveal whose voices we often heard, whose touches we often felt, whose wisdoms come suddenly into the mind when the wisest have shaken their heads and murmured; It cannot be done?" He continues, "Your eyelids are glazed like a courtesan’s, is it that you see the dark groom and master of life?" In these passages, the Praise-singer represents our "human" questions, and he hopes Elesin, in his half-earthly, half-heavenly state, will help him to understand. But Elesin cannot answer him, and all remains a mystery.

Near the end of the story, the theme of understanding again shows through when Elesin is pondering his failure to fulfil the death ritual. He laments his weakness but also his lack of understanding that led to his failure. He realizes that his failure was tied to a misunderstanding, believing that perhaps the intervention of the colonists was the work of the gods. He is frustrated at his weakness and the catastrophe that came to be as a result. Soon after this realization, Iyaloja reinforces the theme of understanding while arguing with Pilkings: "Child," she says, "I have not come to help your understanding. [Points to Elesin] This is the man whose weakened understanding holds us in bondage to you". The play ends with Iyaloja reminding Elesin’s new bride to "forget the dead, forget even the living. Turn your mind only to the unborn". Neither an understanding of people nor death has been reached, but considerable examination and contemplation have occurred. As Iyaloja suggests, one can only concentrate on the future and continue trying to understand the world and the world beyond life.

Yoruba Proverbs

Almost every character in Death and the King's Horseman at some point uses a traditional Yoruba proverb. Through his vast knowledge of Yoruba proverbs, Soyinka is able to endow his play with a strong Yoruba sentiment.

Characters often employ Yoruba proverbs primarily as a means of bolstering their opinions and persuading others to take their point of view.[18]

The Praise-singer gets annoyed with Elesin for his decision to take a new wife and tries to dissuade him:

-

- Because the man approaches a brand-new bride he forgets the long faithful mother of his children.

- Ariyawo-ko-iyale[19]

Similarly, Iyaloja tries to admonish Elesin against his earthly attachments and stay true to the ritual upon which the good of his society depended:

-

- Eating the awusa nut is not so difficult as drinking water afterwards.

- Ati je asala [awusa] ko to ati mu omi si i.[20]

Another common way in which Soyinka uses proverbs is with Elesin. Elesin himself uses several proverbs in order to convince his peers that he is going to comply with their ritual and thus join the ancestors in orun:

-

- The kite makes for wide spaces and the wind creeps up behind its tail; can the kite say less than thank you, the quicker the better?

- Awodi to'o nre Ibara, efufu ta a n'idi pa o ni Ise kuku ya.[21]

-

- The elephant trails no tethering-rope; that king is not yet crowned who will peg an elephant.

- Ajanaku kuro ninn 'mo ri nkan firi, bi a ba ri erin ki a ni a ri erin[21]

-

- The river is never so high that the eyes of a fish are covered.

- Odu ki ikun bo eja l'oju[21]

The final way in which proverbs appear in the play is when Iyaloja and the Praise-singer harass Elesin while he is imprisoned for failing to complete his role within the ritual:

-

- What we have have no intention of eating should not be help up to the nose.

- Ohun ti a ki i je a ki ifif run imu[21]

-

- We said you were the hunter returning home in triumph, a slain buffalo pressing down on his neck; you said wait, I first must turn up this cricket hole with my toes.

- A ki i ru eran erin lori ki a maa f'ese wa ire n'ile[22]

-

- The river which fills up before our eyes does not sweep us away in its flood.

- Odo ti a t'oju eni kun ki igbe 'ni lo[21]

Performances

Written in five acts, it is performed without interruption.[23] "The play is seldom performed outside of Africa. Soyinka himself has directed important American productions, in Chicago in 1979 and at Lincoln Center in New York in 1987, but these productions were more admired than loved. Although respected by critics, Soyinka’s plays are challenging for Westerners to perform and to understand, and they have not been popular successes."[1]

The play was performed at London's Royal National Theatre beginning in April 2009, directed by Rufus Norris, with choreography by Javier de Frutos and starring Lucian Msamati. It was also performed at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival from February 14 to July 5, 2009.[24]

Reviews

Death and The King's Horseman "forge[s] out of this story a metaphor not just for the whole history of Africa and its collision with colonial Europe but a profound meditation on the nature of man, . . . the relationship of life with death and the power of religion, ritual and spirituality in human existence."[25] It is probably Soyinka's greatest work for the theatre and remains one of his most universal and accessible dramatic statements.[citation needed]

One of the play's interpretive problems is Elesin's attempt to commit suicide. As Soyinka conceals the moment when Elesin is interrupted, we do not know whether the interruption prevented his follow through, whether he could not bring himself to commit the act, or whether he just did not know how to perform it. He himself gives conflicting explanations, at one time telling his bride that his attraction to her made him long to stay in the world a while longer ("...perhaps your warmth and youth brought new insights of this world to me and turned my feet leaden on this side of the abyss"), while a few moments later telling the village matriarch that he thought the white man's intervention "might be the hand of the gods".[26]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Gale (January 2006). Marie Rose Napierkowski. ed. "Death and the King's Horseman: Introduction. Drama for Students.". eNotes (Detroit) 10. http://www.enotes.com/death-kings/introduction. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ Soyinka, Wole (2002). Death and the king's horseman. W.W. Norton. p. 5. ISBN 0393322998.

- ^ Henry John Drewal, John Pemberton III, and Rowland Abiodun, Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought (New York: The Center for African Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1989). © The Center for African Art.

- ^ a b c d (id. at 14)

- ^ (id. at 14).

- ^ a b (id. at 14)

- ^ (id. at 23)

- ^ (id at 14,15.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i (id. at 15)

- ^ (id. at 177)

- ^ a b c (id. at 16)

- ^ Barnes, Sandra. Africa's Ogun: Old World and New (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press). Pp 106. © Indiana University Press.

- ^ a b (id. at 266)

- ^ (id. at 129)

- ^ (id. at 145)

- ^ (id. at 110)

- ^ Gikandi, Simon. Introduction of: Death and the King's Horseman: A Norton Critical Edition New York: Norton & Company, 2003. © Norton & Company.

- ^ Richards, David. Death and the King's Horseman and the Masks of Language. Excerpt from: Soyinka, Wole. Death and the King's Horseman: A Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton & Company, 2003. © Norton & Company. Pp196-207.

- ^ (id. at 201)

- ^ (id. at 201)

- ^ a b c d e (id. at 202)

- ^ (id. at 202

- ^ "The Literary Encyclopedia". http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=5727. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ "Death and the King's Horseman". Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Ashland, OR. 2009. http://www.osfashland.org/browse/production.aspx?prod=160. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ "Death and the King's Horseman". 3RC: 3rd Row Center. St. Louis, MO. 2008. http://www.3rdrowcenter.com/productions.php?prodId=277. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Both passages come from Act 5.

External links

Plays The Swamp Dwellers · The Lion and the Jewel · The Trials of Brother Jero · A Dance of the Forests · The Strong Breed · Before the Blackout · Kongi's Harvest · The Road · The Bacchae of Euripides · Madmen and Specialists · Camwood on the Leaves · Jero's Metamorphosis · Death and the King's Horseman · Opera Wonyosi · Requiem for a Futurologist · A Play of Giants · A Scourge of Hyacinths · The Beatification of the Area Boy · King Baabu · Etiki Revu Wetin · Sixty Six

See also Categories:- 1975 plays

- Plays by Wole Soyinka

- Plays set in Africa

- Yoruba culture

- History of Nigeria

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.