- Sarcosuchus

Taxobox

name = "Sarcosuchus"

fossil_range = Fossil range|115|110Aptian -Albian

image_width = 250px

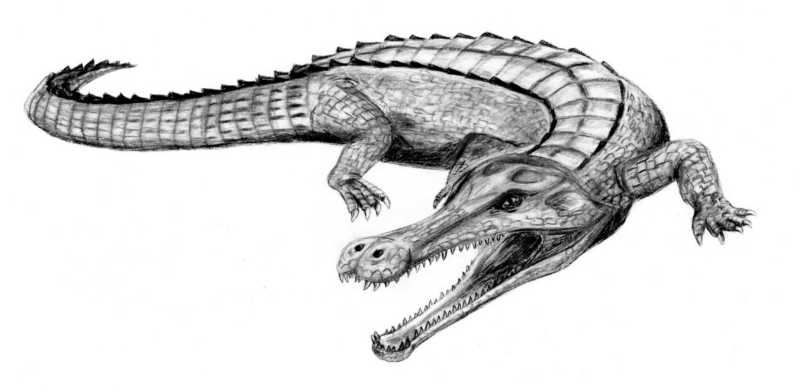

image_caption = Life restoration of "Sarcosuchus imperator"

regnum =Animal ia

phylum =Chordata

classis = Sauropsida

subclassis =Diapsida

infraclassis =Archosauromorpha

unranked_ordo =Mesoeucrocodylia

familia =Pholidosauridae

genus = "Sarcosuchus"

genus_authority = Broin & Taquet, 1966

subdivision_ranks =Species

subdivision =

* "S. imperator" Broin & Taquet, 1966 (type)

* "S. hartii" (Marsh, 1869 (originally "Crocodylus "))"Sarcosuchus" (pronEng|ˌsɑrkoʊˈsuːkəs), meaning 'flesh

crocodile ' and commonly called "SuperCroc", is anextinct genus ofcrocodilian and distant relative of thecrocodile . It dates from the earlyCretaceous Period of what is nowAfrica and is one of the largest giant crocodile-like reptiles that ever lived. It was almost twice as long as the modern saltwater crocodile and weighed approximately 8 to 10 tonnes.Until recently, all that was known of the genus was a few

fossil isedteeth and armour scutes, which were discovered in theSahara Desert by the Frenchpaleontologist Albert-Félix de Lapparent , in the 1940s or 1950s. However, in 1997 and 2000,Paul Sereno discovered half a dozen new specimens, including one with about half the skeleton intact and most of the spine. All of the other giant crocodiles are known only from a few partial skulls, so which is actually the biggest is an open question.Description

When fully mature, "Sarcosuchus" is believed to have been as long as a city

bus (11.2–12.2 meters or 37–40 ft) and weighed up to 8 tonnes (8.75 tons).cite web |url=http://www.supercroc.org/about.htm |title=Fact Sheet |accessdate=2007-09-22 |last=Lyon |first=Gabrielle |work=SuperCroc |publisher=Project Exploration] The largest living crocodilian, thesaltwater crocodile , is less than two-thirds of that length (6.3 meters or 20.6 ft is the longest confirmed individual) and a small fraction of the weight (1,200 kg, or 1.3 tons).The very largest "Sarcosuchus" is believed to have been the oldest. Osteoderm growth rings taken from an 80% grown individual (based on comparison to largest individual found) suggest that "Sarcosuchus" kept growing throughout its entire 50–60 yearaverage life span (Sereno et al., 2001). Modern crocodiles grow at a rapid rate, reaching their adult size in about a decade, then growing more slowly afterwards.Its

skull alone was as big as ahuman adult (1.78 m, or 5 ft 10 inches). The upper jaw overlapped the lower jaw, creating an overbite. The jaws were relatively narrow (especially in juveniles). The snout comprises about 75% of the skull's length (Sereno et al., 2001).The huge

jaw contained 132 thick teeth (Larsson said they were like "railroad spikes" Fact|date=May 2008). The teeth were conical being adapted for grabbing and holding; instead of being narrow, adapted for slashing (like the teeth of some land-dwelling carnivores), and more like that of true crocodilians. "Sarcosuchus" could probably exert a force of 80 kN (18,000 lbf) with its jaw, making it very unlikely that prey could escape. [Dr. Greg M. Erickson, Florida State University [http://www.bio.fsu.edu/faculty-erickson.php Greg Erickson, Faculty page] ]It had a row of bony plates or "

osteoderms ", running down its back, the largest of which were 1 m (3 ft) long. The scutes served as armour and may have helped support its great mass, but also restricted its flexibility Fact|date=May 2008."Sarcosuchus" also had a strange depression at the end of its snout. Called a bulla, it has been compared to the ghara seen in

gharial s. Unlike the ghara, though, the bulla is present in all "Sarcosuchus" skulls that have been found so far. This suggests it was not a sexually selected character (only the malegharial has a ghara). The purpose of this structure remains enigmatic. Sereno and others asked various reptile researchers what their thoughts on this bulla were. Opinions ranged from it being an olfactory enhancer to being connected to a vocalization device (Geology News, 2001).Behaviour and diet

Like true crocodiles, "Sarcosuchus" might have made a wide range of vocalisations, from grunts and squeaks to hisses, growls, barks, bellows and roars. These sounds may have been used by "Sarcosuchus" to stake out territory, attract mates and to communicate with their progeny.

The eye sockets of "Sarcosuchus" rotated upwards and were somewhat telescoped (Sereno et al., 2001). This suggests that the animal probably spent most of its time with the majority of its body submerged, watching the shore for prey.

It seems likely that it ate the large

fish andturtle s of the Cretaceous. As the overhanging jaw and stout teeth are designed for grabbing and crushing, its primary prey may have been large animals and smallerdinosaur s, which it ambushed, dragged into the water, crushed, drowned and then tore apart.It may have come into conflict with "

Suchomimus ", an 11 m (36 ft) theropod dinosaur with a gharial-like snout, whose fossils were found in the same geological formation as "Sarcosuchus". According to Sereno Fact|date=May 2008, "because the ancient animal was so large, it could easily handle huge dinosaurs, including the massive long-necked, small-headedsauropod s that were common in thatAfrica n region". Other crocodilian biologists are skeptical of the animal's "giant killing" capabilities Fact|date=May 2008. The long, thin snout of "Sarcosuchus" was very similar to the thin snouts of the modern gharial, thefalse gharial and theslender-snouted crocodile , all of which are nearly exclusive fish-eaters and incapable of tackling large prey. This can be contrasted to both the modernNile crocodile and the extinct "Deinosuchus ", both of which exhibit very broad, heavy skulls, suitable for dealing with large prey. This, coupled with the abundance of large, lobe-finned fish in its environment, leads many to suggest that, far from being a dinosaur killer, "Sarcosuchus" was simply a large piscivore, a scaled-up version of the modern gharial.However, while the snout of juvenile "Sarcosuchus" strongly resembled modern narrow-snouted crocodiles in width, it expands dramatically in mature individuals (Sereno et al., 2001). While still comparatively narrower than the snout of a Nile crocodile, the snout is still much wider than the snouts of crocodilians like the

gharial . In addition, the teeth do not interlock Fact|date=May 2008, like those of mostly piscivorous crocodilians. This suggests that, like the Nile crocodile, it may have complemented a primarily fish diet with terrestrial animals, at least upon maturity Fact|date=May 2008.It is pertinent to note, though, that the lobe-finned fish that shared the waters with "Sarcosuchus" were often in excess of 1.8 m (6 ft) long and 90 kg (200 lb) in weight Fact|date=May 2008. This raises the possibility of those adaptations, which seem to indicate large or moderate-sized terrestrial prey, may instead have been adaptations for dealing with exceptionally large fish (many species of which possessed a layer of osteoderms, for protection).

Environment

110

million years ago , in the Early Cretaceous, the Sahara was still a great tropicalplain , dotted withlake s and crossed byriver s andstream s that were lined with vegetation. Based on the number of fossils discovered, the aquatic "Sarcosuchus" was probably plentiful in these warm, shallow,freshwater habitats.Unlike modern true crocodiles, which are very similar in size and shape to one another and tend to live in different areas; "Sarcosuchus" was just one of many Crocodyliformes, of different sizes and shapes, all living in the same area Fact|date=May 2008. Four other species of extinct Crocodyliformes were also discovered in the same rock formation along with the "Sarcosuchus", including a dwarf crocodile with a tiny, 8 cm (3 in) long skull Fact|date=May 2008. They filled a diverse variety of ecological niches, instead of competing with each other for resources.

Scientific study

The "Sarcosuchus" remains are from several individuals and include a spine (

vertebrae ), limb bones, hip bones (apelvic girdle ), the bony armored plates that ran down its back (scutes) and more than a half-dozenskull s. Many crocodyliform skulls are thick and heavy Fact|date=May 2008. They tend to be found more frequently than the rest of the body Fact|date=May 2008. This is quite a contrast with dinosaurs, whose relatively fragile skulls rarely become part of thefossil record Fact|date=May 2008.The osteoderms of ancient reptiles have been used to determine age (Erickson & Brochu, 1999). Since they retain

growth ring s, like those found intree s (most other bones 'suffer' remodeling with age, which destroys former growth rings), it is theoretically possible to count the age of the individual that the bones belonged to. One 80% grown specimen was discovered with 40 rings, indicating that it had lived for 40 years. This form of growth rate calculation has been somewhat controversial. Others (Schwimmer, 2002) have criticised this form of growth measurement, as annular rings are harder to determine in a creature that lives in an environment that is without extreme seasonality (such as the Mesozoic). No skeleton was complete enough to measure directly, so the maximum length estimate was calculated by measuring the largest skull and comparing it to modern crocodiles. In modern crocodiles, the skull and body are the same proportion regardless of age or sex (Sereno et al., 2001). The primary difference is that species with a long snout have larger heads in proportion to their bodies than species with relatively broad snouts. The length of "Sarcosuchus" was the average of the expected length of the narrow-snouted gharial and the intermediate-snouted saltwater crocodile, while the mass was the expected mass of the latter. Sereno also measured living crocodilians inIndia andCosta Rica and used that data in his analysis.As part of a

National Geographic Special, Greg Erickson ofFlorida State University , Kent Vliet of theUniversity of Florida and Kristopher Lapping ofNorthern Arizona University provokedAmerican alligator s, at theSt. Augustine Alligator Farm and Zoological Park inFlorida , into biting a bar studded with piezoelectric sensors. The largest alligator they tested was able to exert a force of 9.45 kN (2,125 lbf). By comparing the force exerted by more than 60 animals, they were able to determine that the force exerted was proportional to the size of the animal, which allowed an estimate of the biting power of the "Sarcosuchus". This force was calculated to be 80 kN (18,000 lbf).The giant croc phenomenon

:"With today's crocs, you basically have a period of fast growth, then a little bit of growth — this guy wasn't slowing down."::—Paul C. Sereno Giant crocodiles seem to be a good example of convergence because, according to Schwimmer Fact|date=May 2008, "the idea of really big crocs is a repeat theme in evolution". This may in part be due to body design (the armoured plates of the back can provide structural support to a massive body Fact|date=May 2008) and in part due to environment (water can buoy up their massive bodies) ("See also:"

Cope's law ).A study of another giant crocodilian, "Deinosuchus", indicated that it grew at about the same rate as modern crocodiles, up to 0.5 m (1.5 ft) per year. It was larger because it kept growing, reaching full adulthood in 35 years, instead of 10. While there is a genetic component, growing that large also requires a rich diet. All the different giant crocodiles must have lived in near-perfect environments, with vast areas of warm, shallow water and abundant prey.

"Deinosuchus", which was from the

Late Cretaceous of what is nowNorth America , is also a good example of a giant crocodile that is only distantly related to "Sarcosuchus". "Deinosuchus", which is only known from skulls, had a smaller skull than "Sarcosuchus" Fact|date=May 2008, but a broad snout, like analligator . This means that the skull of the "Deinosuchus" is probably a smaller portion of its total body length than the skull of the long-snouted "Sarcosuchus", so its total size may be as large, or even larger Fact|date=May 2008. Other rivals in size of "Sarcosuchus" are "Purussaurus " from theMiocene of what is nowPeru andBrazil , and "Rhamphosuchus " from the Miocene andPliocene of what is nowIndia . However, their fossils are less complete.The relationship between the giant crocs can be seen in the following simplified evolutionary tree:

*Neosuchia

** "Sarcosuchus"

** OrderCrocodylia

*** SuperfamilyAlligatoroidea

**** "Purussaurus "

**** "Deinosuchus "

**** "Mourasuchus "

*** SuperfamilyGavialoidea

**** "Rhamphosuchus "Classification

"Sarcosuchus" is not an ancestor of modern crocodiles. Also it is not a crocodilian in the phylogenetic definition of the term. A crocodilian is any member of the

clade Crocodilia . Crocodilia includes all modern forms (such ascrocodile s proper,alligator s etc) and their immediate prehistoric relatives. "Sarcosuchus" is a member of the family Pholidosauridae, more distantly related to today's crocodilians."Crocodile" is a term commonly used in a much broader sense. The first 'crocodile-like reptiles' (the

Crocodylomorpha ), which split from the bird-line ofarchosaur s (the group of reptiles that include dinosaurs, pterosaurs and birds) about 230 million years ago (in theLate Triassic ), looked somewhat like modern crocodilians. They had long legs, long bodies covered with armour.Until the 1980s, the pholidosaurids were classified as part of the presumed suborder "

Mesosuchia ", within the orderCrocodylia . However, Benson and Clark determined in 1988 that Mesosuchia was aparaphyletic group, containing the ancestor of all modern crocodiles. A simplified evolutionary tree (Sereno, 1998):*

Crocodylomorpha

**Mesoeucrocodylia

***Metasuchia

****Neosuchia

*****Pholidosauridae

****** "Sarcosuchus"

***** Crocodylia (modern crocodiles)Teeth and osteoderms found in

Brazil belong to a close relative of "Sarcosuchus". This is possibly evidence that land bridges betweenAfrica andSouth America existed much later than was previously believed.On the other hand, based on the structure of the snout, the closest relative of "Sarcosuchus" is the pholidosaurid"

Terminonaris ", with "Dyrosaurus " and "Pholidosaurus " as slightly more distant relatives. As a group, they are narrow-snouted fish-eaters from saltwater environments, except for the broader snouted, river-dwelling "Sarcosuchus".Desert discoveries

The fossils were discovered in

Gadoufaoua, Niger in theTénéré Desert , which is part of the Sahara. The first "Sarcosuchus" teeth and scutes were recovered by the French paleontologist Albert-Félix de Lapparent, in the 1940s or 1950s. It was 1964, however, before a skull was discovered bygeologist s and brought to the attention ofPhilippe Taquet . He shipped it to Paris, where it was examined byFrance de Broin . Together, they formally named and described the species, in 1966, before returning the specimen to Niger.The crocodile was given the name "Sarcosuchus imperator", which is dervived from "sarco" (meaning 'flesh'), "suchus" (meaning 'crocodile') and "imperator" (

Latin , meaning 'emperor'). Theholotype specimen is MNN 604, which indicates that it is 604th exhibit at theMusee National du Niger .The next major expedition was Paul C. Sereno's trip, in 1997 and the follow-up trip in 2000. He recovered partial skeletons, numerous skulls and 20 tons of assorted other fossils from the deposits of the El Rhaz Formation, which has been dated as

Aptian toAlbian stages of the late Cretaceous. It took about a year to prepare the "Sarcosuchus" remains. The discovery was then published onOctober 25 ,2001 , in the scientific journal "Science" by Paul C. Sereno of theUniversity of Chicago and National Geographic's Explorer-in-Residence, Hans C. E. Larsson fromYale University and theUniversity of Toronto (formerly a student at the University of Chicago), Christian Sidor of theNew York College of Osteopathic Medicine inOld Westbury, New York and Boubé Gado of theInstitut de Recherches en Sciences Humaines inNiamey ,Niger .References

*Erickson, G.M. and Brochu, C.A. 1999. How the "Terror Crocodile" Grew so Big. Nature. Vol. 398 pgs 205-206*" [http://www.geolsoc.org.uk/template.cfm?name=Saurosuchus Giant croc and a right load of bulla] ." Geology News. 2001, November (author unknown). Last accessed: 11 Apr 06

* Sereno, P.; Larsson, H.C.; Sidor, C.A.; Gado, B. 2001. " [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/294/5546/1516 The Giant Crocodyliform Sarcosuchus from the Cretaceous of Africa] ". "Science" Vol. 294, pgs 1516–1519. (published online on October 25, 2001). "See also:" " [http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/data/1066521/DC1/1 Supplementary Information for Sereno "et al."] ". (131 MB PDF)

*Schwimmer, D. 2002. King of the Crocodylians: The Paleobiology of "Deinosuchus". Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34087-X

* Sloan, C. 2002. "SuperCroc and the Origin of Crocodiles." National Geographic. ISBN 0-7922-6691-9. (children's book)

Footnotes

Further viewing

* "National Geographic Special on SuperCroc." National Geographic Channel, December, 2001.

External links

*imdb title|id=0304766|title=SuperCroc

* " [http://prehistoricsillustrated.com/dms_sarcosuchus.html "Sarcosuchus imperator] ". "Prehistorics Illustrated". (illustrations)

* " [http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn?pagename=article&node=&contentId=A53118-2001Oct25 African fossil find: 40-foot crocodile] ". Guy Gugliotta. "Washington Post", October 26, 2001. Retrieved November 17, 2004.

* " [http://www.supercroc.com/index.htm SuperCroc: Sarcosuchus imperator] ". Gabrielle Lyon. Retrieved November 17, 2004.

* " [http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/10/1025_supercroc.html 'SuperCroc' fossil found in Sahara] ". D. L. Parsell. "National Geographic News", October 25, 2001. Retrieved November 17, 2004.

* " [http://www.projectexploration.org/niger2000/index.htm Dinosaur Expedition 2000] ". Paul C. Sereno. Retrieved November 17, 2004.

* " [http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/04/0404_020408_supercrocbite.html SuperCroc's jaws were superstrong, study shows] ". John Roach. "National Geographic News", April 4, 2003. Retrieved November 17, 2004.

* " [http://chronicle.uchicago.edu/011101/supercroc.shtml Sereno, team discover prehistoric giant Sarcosuchus imperator in African desert] ." Steve Koppes. "The University of Chicago Chronicle", volume 21, number 4, November 1, 2001. Retrieved November 17, 2004.

* [http://www.staabstudios.com/portfolio/croc/croc1.html Making of the "Sarcosuchus" exhibit]

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.