- Dominion

-

- This article is about the Dominions of the British Empire and of the Commonwealth of Nations. For other uses, see Dominion (disambiguation)

A dominion, often Dominion,[1] refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century.[2] They have included (at varying times) Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, the Union of South Africa, and the Irish Free State. Since 1948, the term "dominion" has been used to denote those independent nations of the British Commonwealth that shared with the United Kingdom the same person as their respective monarch. These have included (at varying times) Pakistan, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Kenya, and others, in addition to the earlier dominions. Many of the former British colonies that were granted independence in the decades following World War II were called "Dominions" in their constitutions of independence.[citation needed] In many cases, these countries soon became republics, thus ending their status as Dominions (for example, India, Pakistan, Kenya, and Nigeria). The United Kingdom and the other remaining monarchies are today referred to as Commonwealth realms.

Contents

Definition

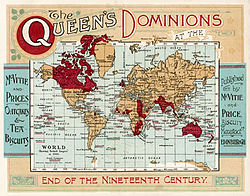

Map of the British Empire under Queen Victoria at the end of the nineteenth century. Note that "dominions" refers to all territories belonging to the Crown

Map of the British Empire under Queen Victoria at the end of the nineteenth century. Note that "dominions" refers to all territories belonging to the Crown

In English common law the Dominions of the British Crown referred to all the realms and territories under the sovereignty of the Crown. For example, the Order in Council that annexed the island of Cyprus in 1914 provided that:

the said Island shall be annexed to and form part of His Majesty's Dominions, and the said Island is annexed accordingly".[3]Use of the word Dominion, to refer to a particular territory, dates back to the 16th century, and was used to describe Wales from 1535 to around 1800.[4][5] Dominion, as an official title, was first conferred on Virginia, circa 1660 and the Dominion of New England in 1686. These dominions never had semi-autonomous or self-governing status. On the other hand, under the British North America Act 1867, eastern Canada received the status of "Dominion" upon the Confederation in 1867 of several British possessions in North America.

The Colonial Conference of 1907 was the first time that the self-governing colonies of Canada and the Commonwealth of Australia were referred to collectively as Dominions.[6] Two other self-governing colonies, New Zealand and Newfoundland, were also granted the status of Dominions that year. These were followed by the Union of South Africa (1910) and the Irish Free State (1922). At the time of the founding of the League of Nations, the League Covenant made specific provisions for the admission of any "fully self-governing state, Dominion, or Colony,"[7] the implication being that "Dominion status was something between that of a ‘Colony’ and a ‘State’."[8]

Dominion status was formally defined in the Balfour Declaration of 1926, which recognised these countries as "autonomous Communities within the British Empire", thus acknowledging them as political equals of the United Kingdom; the Statute of Westminster 1931 converted this status into legal reality, making them essentially independent members of what was then called the British Commonwealth.

Following the Second World War, the decline of British colonialism led to Dominions generally being referred to as Commonwealth realms, the use of the word gradually diminished within these countries after this time. Nonetheless, though disused, it remains Canada's legal title;[9] moreover, the phrase Her Majesty's Dominions is still used occasionally in current-day legal documents in the United Kingdom.[10]

Historical development

Overseas dominions

Dominions originally referred to any land in possession of the British Empire. Oliver Cromwell's full title in the 1650s was the "Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, and the dominions thereto belonging". In 1660, King Charles II gave the Colony of Virginia the title of "Dominion" (in name only) in gratitude for Virginia's loyalty to the Crown during the English Civil War.[citation needed] The Commonwealth of Virginia, a State of the United States still has "The Old Dominion" as one of its nicknames. The name "Dominion" also occurred in that of the short-lived Dominion of New England (1686 – 89). In all of these cases, the word Dominion implied being a subject of the Empire.[citation needed]

Responsible government

The New Zealand Observer (1907) shows Prime Minister Joseph Ward as a pretentious dwarf beneath a massive ‘dominion’ top hat. The caption reads: The Surprise Packet:

The New Zealand Observer (1907) shows Prime Minister Joseph Ward as a pretentious dwarf beneath a massive ‘dominion’ top hat. The caption reads: The Surprise Packet:

Canada: "Rather large for him, is it not?"

Australia: "Oh his head is swelling rapidly. The hat will soon fit."The foundation of "Dominion" status was the achievement of internal self-rule in the form of "responsible government". Responsible government in British colonies began to emerge in the 1840s—typically with Nova Scotia cited as the first colony to achieve it in early 1848—and then being granted to most of the major settler colonies—British North America, Australia, and New Zealand—by 1856. Most of the territories of British North America were joined in a federal union between 1867 and 1873 under the authority of the British North America Act of 1867, which called the new entity a "Dominion" (Section 3 of the British North America Act of 1867).

The Commonwealth of Australia, and New Zealand, were both designated as dominions in 1907. The Australian Constitutions Act 1850[11] established the machinery for the four then existing Australian colonies (namely New South Wales, Tasmania, Western Australia, and South Australia) to establish local parliaments and responsible governments once certain conditions had been met. This act also separated the State of Victoria from New South Wales and established it as a separate colony—carried out in 1851—with a similar capability to attain self-government. New South Wales,[12] Victoria,[13] South Australia,[14] and Tasmania,[15] along with New Zealand, attained responsible governments soon after in 1856. The self-government for Western Australia was delayed until 1891, mainly because of its continuing dependence, financially, on the government of the United Kingdom.[16] Queensland was separated from New South Wales and established as a separate colony in the year 1859.[17] These acts left a large piece of territory in northern Australia as being still part (technically) of New South Wales, though physically separated from it. This land was transferred in part to Queensland and in part to South Australia in 1863.[18] In 1911, the large area of its land that had been governed by South Australia was transferred to the direct control of the Commonwealth of Australia to form the Northern Territory.[19]

The Union of South Africa became a Dominion in 1910. It had contained several colonies that had become self-governing earlier, with the Cape Colony being the first in 1872. This was followed by Natal in 1893, Transvaal in 1906, and the Orange River Colony in 1907.

Canada and Confederation

The 20th century usage of the term "Dominion" can be traced to a suggestion by Samuel Leonard Tilley at the London Conference of 1866 discussing the confederation of five of the British North American possessions, the Province of Canada (subsequently becoming the Province of Ontario and the Province of Quebec), New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island into "One Dominion under the Name of Canada", the first internal federation in the British Empire. Tilley's suggestion was taken from the 72nd Psalm, verse eight, "He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, and from the river unto the ends of the earth," which is echoed in the national motto, "A Mari Usque Ad Mare."[20] The new government of Canada under the British North America Act of 1867 began to use the phrase "Dominion of Canada" to designate the new, larger nation. However, neither the Confederation nor the adoption of the title of "Dominion" granted extra autonomy or new powers to this new federal level of government.[21][22] Senator Eugene Forsey wrote that the powers acquired since the 1840s that established the system of responsible government in Canada would simply be transferred to the new Dominion government:

- "By the time of Confederation in 1867, this system had been operating in most of what is now central and eastern Canada for almost 20 years. The Fathers of Confederation simply continued the system they knew, the system that was already working, and working well."[22]

The constitutional scholar Andrew Heard has established that Confederation did not legally change Canada's colonial status to anything approaching its later status of a Dominion.

- At its inception in 1867, Canada's colonial status was marked by political and legal subjugation to British Imperial supremacy in all aspects of government—legislative, judicial, and executive. The Imperial Parliament at Westminster could legislate on any matter to do with Canada and could override any local legislation, the final court of appeal for Canadian litigation lay with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, the Governor General had a substantive role as a representative of the British government, and ultimate executive power was vested in the British Monarch—who was advised only by British Ministers in its exercise. Canada's independence came about as each of these sub-ordinations was eventually removed.[21]

Heard went on to document the sizeable body of legislation passed by the British Parliament in the latter part of the 19th century that upheld and expanded its Imperial supremacy to constrain that of its colonies, including the new Dominion government in Canada.

- When the Dominion of Canada was created in 1867, it was granted powers of self-government to deal with all internal matters, but Britain still retained overall legislative supremacy. This Imperial supremacy could be exercised through several statutory measures. In the first place, the British North America Act of 1867 provided in Section 55 that the Governor General may reserve any legislation passed by the two Houses of Parliament for "the signification of Her Majesty's pleasure," which is determined according to Section 57 by the British Monarch in Council. Secondly, Section 56 provides that the Governor General must forward to "one of Her Majesty's Principal Secretaries of State" in London a copy of any Federal legislation that has been assented to. Then, within two years after the receipt of this copy, the (British) Monarch in Council could disallow an Act. Thirdly, at least, four pieces of Imperial legislation constrained the Canadian legislatures. The Colonial Laws Validity Act of 1865 provided that no colonial law could validly conflict with, amend, or repeal Imperial legislation that either explicitly, or by necessary implication, applied directly to that colony. The Merchant Shipping Act of 1894, as well as the Colonial Courts of Admiralty Act of 1890 required reservation of Dominion legislation on those topics for approval by the British Government. Also, the Colonial Stock Act of 1900 provided for the disallowance of any Dominion legislation the British government felt would harm British stockholders of Dominion trustee securities. Most importantly, however, the British Parliament could exercise the legal right of supremacy that it possessed over common law to pass any legislation on any matter affecting the colonies.[21]

Furthermore, for decades none of the Dominions was allowed to have its own embassies or consulates in foreign countries. All matters concerning international travel, commerce, etc., had to be transacted through British embassies and consulates. For example, all transactions concerning visas and lost or stolen passports by citizens of the Dominions were carried out at British diplomatic offices. It was not until the late 1930s and early 40s that the Dominion governments were allowed to establish their own embassies, and the first two of these that were established by the Dominion governments in Ottawa and in Canberra were both established in Washington, D.C. in the United States. Nowadays, it is hard to imagine the federal governments of the United States and of Canada not having their own embassies in Ottawa and in Washington.

However, as Heard later explained, the British government seldom invoked its powers over Canadian legislation. Indeed, in the Canadian context, British legislative powers over Canadian domestic policy were largely theoretical and their exercise was increasingly unacceptable in the 1870s and 1880s. The rise to the status of a Dominion and then full independence for Canada and other possessions of the British Empire did not occur by the granting of titles or similar recognition by the British Parliament but by initiatives taken the new governments of certain former British dependencies to assert their independence and to establish constitutional precedents.

- What is remarkable about this whole process is that it was achieved with a minimum of legislative amendments. Much of Canada's independence arose from the development of new political arrangements, many of which have been absorbed into judicial decisions interpreting the constitution—with or without explicit recognition. Canada's passage from an integral part of the British Empire to an independent member of the Commonwealth richly illustrates the way fundamental constitutional rules evolved through the interaction of constitutional convention, international law, and municipal statute and case law,[21] although British statutory law was also involved.

The Colonial Conference of 1907

Issues of colonial self-government spilled into foreign affairs with the Boer War (1899–1902). The self-governing colonies contributed significantly to British efforts to stem the insurrection, but assured that they set the conditions for participation in these wars. Colonial governments repeatedly acted to assure that they determined the extent of their peoples' participation in imperial wars in the military build-up to the First World War.

The assertiveness of the self-governing colonies was recognised in the Colonial Conference of 1907, which implicitly introduced the idea of the Dominion as a self-governing colony by referring to Canada and Australia as Dominions. It also retired the name "Colonial Conference" and mandated that meetings take place regularly to consult Dominions in the running the foreign affairs of the empire.

The Colony of New Zealand, which chose not to take part in Australian federation, quickly became the Dominion of New Zealand on 26 September 1907; Newfoundland became a Dominion on the same day. The newly-created Union of South Africa would also be referred to as a Dominion in 1910.

The First World War and the Treaty of Versailles

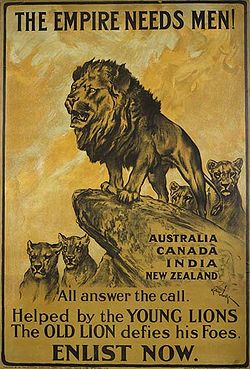

The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee produced this First World War poster. Designed by Arthur Wardle, the poster urges men from the Dominions of the British Empire to enlist in the war effort.

The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee produced this First World War poster. Designed by Arthur Wardle, the poster urges men from the Dominions of the British Empire to enlist in the war effort.

The initiatives and contributions of British colonies to the British war effort in the First World War were recognised by Britain with the creation of the Imperial War Cabinet in 1917, which gave them a say in the running of the war. Dominion status as self-governing states, as opposed to symbolic titles granted various British colonies, waited until 1919, when the self-governing Dominions signed the Treaty of Versailles independently of the British government and became individual members of the League of Nations. This ended the purely colonial status of the dominions.

- "The First World War ended the purely colonial period in the history of the Dominions. Their military contribution to the Allied war effort gave them claim to equal recognition with other small states and a voice in the formation of policy. This claim was recognised within the Empire by the creation of the Imperial War Cabinet in 1917, and within the community of nations by Dominion signatures to the Treaty of Versailles and by separate Dominion representation in the League of Nations. In this way the "self-governing Dominions", as they were called, emerged as junior members of the international community. Their status defied exact analysis by both international and constitutional lawyers, but it was clear that they were no longer regarded simply as colonies of Britain."[23]

The Irish Free State

The Irish Free State set up in 1922, after the Anglo-Irish War was the first Dominion to appoint a non-British, non-aristocratic Governor-General, when Timothy Michael Healy took the position in 1922. Dominion status was never popular in the Irish Free State where people saw it as a face-saving measure for a British government unable to countenance a republic in what had previously been the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Successive Irish governments undermined the constitutional links with Britain, until they were severed completely in 1949. In 1937 Ireland adopted, almost simultaneously, both a new constitution that included powers for a President of Ireland and a law confirming the king's role of head of state in external relations.

The Second Balfour Declaration and the Statute of Westminster

The Balfour Declaration of 1926, and the subsequent Statute of Westminster, 1931, restricted Britain's ability to pass or affect laws outside of its own jurisdiction. Significantly, Britain initiated the change to complete independence for the Dominions. World War I left Britain saddled with enormous debts, and the Great Depression had further reduced Britain's ability to pay for defence of its empire. In spite of popular opinions of empires, the larger Dominions were reluctant to leave the protection of the then-superpower. For example, many Canadians felt that being part of the British Empire was the only thing that had prevented them from being absorbed into the United States.

Until 1931, Newfoundland was referred to as a colony of the United Kingdom, as for example, in the 1927 reference to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council to delineate the Quebec-Labrador boundary. Full autonomy was granted by the United Kingdom parliament with the Statute of Westminster in December 1931. However, the government of Newfoundland "requested the United Kingdom not to have sections 2 to 6[—]confirming Dominion status[—]apply automatically to it[,] until the Newfoundland Legislature first approved the Statute, approval which the Legislature subsequently never gave." In any event, Newfoundland's letters patent of 1934 suspended self-government and instituted a "Commission of Government," which continued until Newfoundland became a province of Canada in 1949. It is the view of some constitutional lawyers that—although Newfoundland chose not to exercise all of the functions of a Dominion like Canada—its status as a Dominion was "suspended" in 1934, rather than "revoked" or "abolished".

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland and South Africa (prior to becoming a republic and leaving the Commonwealth in 1961), with their large populations of European descent, were sometimes collectively referred to as the "White Dominions." Today Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are sometimes referred to collectively as the "White Commonwealth."[citation needed]

The United Kingdom and its component parts never aspired to the title of "Dominion," remaining anomalies within the network of free and independent equal members of the empire and Commonwealth. However, the idea has on occasions been floated by some in Northern Ireland as an alternative to a United Ireland if they felt uncomfortable within the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

The Dominions

Australia

Four colonies of Australia had enjoyed responsible government since 1856: New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia.[24] Queensland had responsible government soon after its founding in 1859[25] but, because of ongoing financial dependence on Britain, Western Australia became the last Australian colony to attain self-government in 1890.[26] During the 1890s, the colonies voted to unite and in 1901 they were federated under the British Crown as the Commonwealth of Australia by the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act. The Constitution of Australia had been drafted in Australia and approved by popular consent. Thus Australia is one of the few countries established by a popular vote.[27] Under the second Balfour Declaration, the federal government was regarded as coequal with (and not subordinate to) the British and other Dominion governments, and this was given formal legal recognition in 1942 (when the Statute of Westminster was retroactively adopted to the commencement of the Second World War 1939). In 1930, the Australian Prime Minister, James Scullin, reinforced the right of the overseas Dominions to appoint native-born governors-general, when he advised King George V to appoint Sir Isaac Isaacs as his representative in Australia, against the wishes of the opposition and officials in London. The governments of the states (called colonies before 1901) remained under the Commonwealth but retained links to the UK until the passage of the Australia Act 1986 thus becoming fully independent.[28]

Canada

See also: Name of CanadaDominion is the legal title conferred on Canada in the Constitution of Canada, namely the Constitution Act, 1867 (British North America Acts), and describes the resulting political union. Specifically, the preamble of the BNA Act indicates:

- Whereas the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick have expressed their Desire to be federally united into One Dominion under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom ...

and, furthermore, sections 3 and 4 indicate that the provinces:

- ... shall form and be One Dominion under the Name of Canada; and on and after that Day those Three Provinces shall form and be One Dominion under that Name accordingly.

- Unless it is otherwise expressed or implied, the Name Canada shall be taken to mean Canada as constituted under this Act.

Usage of the term Dominion of Canada was sanctioned as the country's formal political name in 1867 and it predates the general use of the term 'dominion' as applied to the other autonomous regions of the British Empire in 1907.

Some still read the BNA Act passage as specifying this phrase – rather than Canada alone – as the name. The term Dominion of Canada does not appear in the 1867 act nor in the Constitution Act, 1982 but does appear in the Constitution Act, 1871, other contemporaneous texts, and subsequent bills. References to the Dominion of Canada in later acts, such as the Statute of Westminster, do not clarify the point because all nouns were formally capitalised in British legislative style. Indeed, in the original text of the BNA Act, "One" and "Name" were also capitalised.

Frank Scott theorised that Canada's status as a Dominion ended with the Canadian parliament's declaration of war on Germany on 9 September 1939.[29]

From the 1950s, the federal government began to phase out the use of Dominion, which had been used largely as a synonym of "federal" or "national" such as "Dominion building" for a post office, "Dominion-provincial relations", and so on. The last major change was renaming the national holiday from Dominion Day to Canada Day in 1982. Official bilingualism laws also contributed to the disuse of dominion, as it has no acceptable equivalent in French.

While the term may be found in older official documents, and the Dominion Carillonneur still tolls at Parliament Hill, it is now hardly used to distinguish the federal government from the provinces or (historically) Canada before and after 1867. Nonetheless, the federal government continues to produce publications and educational materials that specify the currency of these official titles.[30][31][32]

Defenders of the title Dominion—including monarchists who see signs of creeping republicanism in Canada—take comfort in the fact that the Constitution Act, 1982 does not mention and therefore does not remove the title, and that a constitutional amendment is required to change it.[33]

The word Dominion has been used with other agencies, laws, and roles:

- Dominion Carillonneur – official responsible for playing the carillons at the Peace Tower since 1916

- Dominion Day (1867–1982) – holiday marking Canada's national day; now called Canada Day

- Dominion Observatory (1905–1970) – weather observatory in Ottawa; now used as Office of Energy Efficiency, Energy Branch, Natural Resources Canada

- Dominion Lands Act (1872) – federal lands act; repealed in 1918

- Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1918–1971) – superseded by Statistics Canada

- Dominion Police (1867–1920) – merged to form the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

- Dominion Astrophysical Observatory (1918–1975); now operated as National Research Council (Canada) Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics

- Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory (1960–present); now operated by National Research Council (Canada)

- Dominion of Canada Rifle Association founded in 1868 and incorporated by an Act of Parliament in 1890

Toronto-Dominion Bank (founded as the Dominion Bank in 1871 and later merged with the Bank of Toronto), the Dominion of Canada General Insurance Company (founded in 1887), the Dominion Institute (created in 1997), and Dominion (founded in 1927, renamed as Metro stores beginning in August 2008) are notable Canadian corporations not affiliated with government that have used Dominion as a part of their corporate name.

Ceylon/Sri Lanka

Ceylon, which, as a crown colony, was originally promised "fully responsible status within the British Commonwealth of Nations", was formally granted independence as a Dominion in 1948. In 1972 it adopted a republican constitution to become the Free, Sovereign and Independent Republic of Sri Lanka. By a new constitution in 1978, it became the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

India and Pakistan

India acquired responsible government in 1909, though the first Parliament did not meet until 1919.[34] India and Pakistan separated as independent dominions in 1947. India became a republic in 1950[34] and Pakistan adopted a republican form of government in 1956.[35]

Irish Free State/Ireland

The Irish Free State was a British Dominion between 1922 and 1949. In 1937 the Irish people established a new state with the name of "Ireland" under a new constitution and ceased participating in Commonwealth conferences and events. However, the United Kingdom and other members of the Commonwealth continued to regard Ireland as being a dominion owing to the unusual role accorded to the British Monarch under the Irish External Relations Act. Ultimately, however, Ireland's Oireachtas passed the Republic of Ireland Act, which came into force in 1949 and unequivocally ended Ireland's links with the British Monarch and the Commonwealth.

On establishment of the Irish Free State on 6 December 1922, with dominion status to be in the likeness of Canada, provision was made for Northern Ireland to join the new dominion but with the right to opt out. However, as was widely expected at the time, on the day after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Parliament of Northern Ireland chose, under the terms of that treaty, to opt out.[36]

Newfoundland

The colony of Newfoundland enjoyed responsible government from 1855-1934.[37] It was among the colonies declared dominions in 1907. Following the recommendations of a Royal Commission, parliamentary government was suspended in 1934.[38] In 1949, the Dominion of Newfoundland joined Canada and the legislature was restored.[39]

New Zealand

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 gave the colony of New Zealand its own Parliament (General Assembly) and home rule in 1852.[40] In 1907 New Zealand was proclaimed the Dominion of New Zealand.[41] New Zealand, Canada, and Newfoundland actually used the word dominion in the official title of the nation, whereas Australia used the name Commonwealth of Australia and South Africa used the name Union of South Africa. New Zealand adopted the Statute of Westminster in 1947[41] and in the same year, legislation passed in London gave New Zealand full powers to amend its own constitution. In 1986, the New Zealand parliament passed the Constitution Act 1986, which repealed the Constitution Act of 1852 thus becoming fully independent of the United Kingdom.[42]

South Africa

The Union of South Africa was formed in 1910 from the four self-governing colonies of the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, the Transvaal, and the Orange Free State (the last two were former Boer republics).[43] The South Africa Act 1909 provided for a Parliament consisting of a Senate and a House of Assembly. The provinces had their own legislatures. In 1961, the Union of South Africa adopted a new constitution, left the Commonwealth, and became the present-day Republic of South Africa.[44]

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a special case in the British Empire. Although it was never a dominion, it was treated as a dominion in many respects. Southern Rhodesia was formed in 1923 out of the territories of the British South Africa Company and established as a self-governing colony with substantial autonomy on the model of the dominions. However, the imperial authorities in London continued to retain direct powers over native affairs. Southern Rhodesia was not included as one of the territories that were mentioned in the 1931 Statute of Westminster although relations with Southern Rhodesia were administered in London through the Dominion Office, not the Colonial Office. When the dominions were first treated as foreign countries by London for the purposes of diplomatic immunity in 1952, Southern Rhodesia was also included in the list of territories concerned. This semi-dominion status continued in Southern Rhodesia even for the ten years, 1953–1963, when it was joined with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland in the Central African Federation, even though the latter two continued with their own status as British protectorates. When Northern Rhodesia was given independence in 1964 it adopted the new name of Zambia, and Southern Rhodesia simply reverted to the name Rhodesia. Rhodesia declared unilateral independence from Britain in 1965 as a result of being pressed into accepting the principles of black majority rule. London regarded this state of unilateral declaration of independence as illegal. It applied sanctions and expelled Rhodesia from the sterling area. Nevertheless, Rhodesia continued with its dominion style constitution until 1970, and continued to issue British passports to its citizens. These Rhodesian-issued British passports were only recognised by Portugal and South Africa. In the period from 1965 to 1970, the Rhodesian government continued its loyalty to the Sovereign despite being in a state of rebellion against Her Majesty's government in London. However, in 1970, Rhodesia adopted a republican constitution and in 1980 it was finally granted legal independence by the UK following the transition to black majority rule. The new name of Zimbabwe was then adopted.

Foreign relations

Initially, the Foreign Office of the United Kingdom conducted the foreign relations of the Dominions. A Dominions section was created within the Colonial Office for this purpose in 1907. Canada set up its own Department of External Affairs in June 1909, but diplomatic relations with other governments continued to operate through the governors-general, Dominion High Commissioners in London (first appointed by Canada in 1880; Australia followed only in 1910), and British legations abroad. Britain deemed her declaration of war against Germany in August 1914 to extend to all territories of the Empire without the need for consultation, occasioning some displeasure in Canadian official circles and contributing to a brief anti-British insurrection by Afrikaner militants in South Africa later that year. A Canadian War Mission in Washington, D.C. dealt with supply matters from February 1918 to March 1921.

Although the Dominions had had no formal voice in declaring war, each became a separate signatory of the June 1919 peace Treaty of Versailles, which had been negotiated by a British-led united Empire delegation. In September 1922, Dominion reluctance to support British military action against Turkey influenced Britain's decision to seek a compromise settlement. Diplomatic autonomy soon followed, with the U.S.-Canadian Halibut Treaty (March 1923) marking the first time an international agreement had been entirely negotiated and concluded independently by a Dominion. The Dominions Section of the Colonial Office was upgraded in June 1926 to a separate Dominions Office; however, initially, this office was held by the same person that held the office of Secretary of State for the Colonies.

The principle of Dominion equality with Britain and independence in foreign relations was formally recognised by the Balfour Declaration, adopted at the Imperial Conference of November 1926. Canada's first permanent diplomatic mission to a foreign country opened in Washington, D.C. in 1927. In 1928, Canada obtained the appointment of a British high commissioner in Ottawa, separating the administrative and diplomatic functions of the governor-general and ending the latter's anomalous role as the representative of the British government in relations between the two countries. The Dominions Office was given a separate secretary of state in June 1930, though this was entirely for domestic political reasons given the need to relieve the burden on one ill minister whilst moving another away from unemployment policy. The Balfour Declaration was enshrined in the Statute of Westminster 1931 when it was adopted by the British Parliament and subsequently ratified by the Dominion legislatures.

Britain's declaration of hostilities against Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939 tested the issue. Most took the view that the declaration did not commit the Dominions. Ireland chose to remain neutral. At the other extreme, the conservative Australian government of the day, led by Robert Menzies, took the view that, since Australia had not adopted the Statute of Westminster, it was legally bound by the UK declaration of war—which had also been the view at the outbreak of World War I—though this was contentious within Australia. Between these two extremes, New Zealand declared that as Britain was or would be at war, so it was too. This was, however, a matter of political choice rather than legal necessity. Canada issued its own declaration of war after a recall of Parliament, as did South Africa after a delay of several days (South Africa on September 6, Canada on September 10). Ireland, which had negotiated the removal of British forces from its territory the year before, chose to remain neutral throughout the war. There were soon signs of growing independence from the other Dominions: Australia opened a diplomatic mission in the US in 1940, as did New Zealand in 1941, and Canada's mission in Washington gained embassy status in 1943.

From Dominions to Commonwealth realms

The prime ministers of Britain and the four major dominions at the 1944 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference. Left to right: William Lyon Mackenzie King (Canada); Jan Smuts (South Africa); Winston Churchill (UK); Peter Fraser (New Zealand); John Curtin (Australia).

The prime ministers of Britain and the four major dominions at the 1944 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference. Left to right: William Lyon Mackenzie King (Canada); Jan Smuts (South Africa); Winston Churchill (UK); Peter Fraser (New Zealand); John Curtin (Australia).

Initially, the Dominions conducted their own trade policy, some limited foreign relations and had autonomous armed forces, although the British government claimed and exercised the exclusive power to declare wars. However, after the passage of the Statute of Westminster the language of dependency on the Crown of the United Kingdom ceased, where the Crown itself was no longer referred to as the Crown of any place in particular but simply as "the Crown." Arthur Berriedale Keith, in Speeches and Documents on the British Dominions 1918-1931, stated that "the Dominions are sovereign international States in the sense that the King in respect of each of His Dominions (Newfoundland excepted) is such a State in the eyes of international law." After then, those countries that were previously referred to as "Dominions" became independent realms where the sovereign reigns no longer as the British monarch, but as monarch of each nation in its own right, and are considered equal to the UK and one another.

World War II, which fatally undermined Britain's already weakened commercial and financial leadership, further loosened the political ties between Britain and the Dominions. Australian Prime Minister John Curtin's unprecedented action (February 1942) in successfully countermanding an order from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill that Australian troops be diverted to defend British-held Burma (the 7th Division was then en route from the Middle East to Australia to defend against an expected Japanese invasion) demonstrated that Dominion governments might no longer subordinate their own national interests to British strategic perspectives. To ensure that Australia had full legal power to act independently, particularly in relation to foreign affairs, defence industry and military operations, and to validate its past independent action in these areas, Australia formally adopted the Statute of Westminster in October 1942[45] and backdated the adoption to the start of the war in September 1939.

The Dominions Office merged with the India Office as the Commonwealth Relations Office upon the independence of India and Pakistan in August 1947. The last country officially made a Dominion was Ceylon in 1948. The term "Dominion" fell out of general use thereafter. Ireland ceased to be a member of the Commonwealth on 18 April 1949, upon the coming into force of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948. This formally signaled the end of the former dependencies' common constitutional connection to the British crown. India also adopted a republican constitution in January 1950. Unlike many dependencies that became republics, Ireland never re-joined the Commonwealth, which agreed to accept the British Monarch as head of that association of independent states.

The independence of the separate realms was emphasised after the accession of Queen Elizabeth II in 1952, when she was proclaimed not just as Queen of the UK, but also Queen of Canada, Queen of Australia, Queen of New Zealand, and of all her other "realms and territories" etc. This also reflected the change from Dominion to realm; in the proclamation of Queen Elizabeth II's new titles in 1953, the phrase "of her other Realms and Territories," replaced "Dominion" with another mediaeval French word with the same connotation, "realm" (from royaume). Thus, recently, when referring to one of those sixteen countries within the Commonwealth of Nations that share the same monarch, the term Commonwealth realm has come into common usage instead of Dominion to differentiate the Commonwealth nations that continue to share the monarch as head of state (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Jamaica, etc.) from those that do not (India, Pakistan, South Africa, etc.). The term "Dominion" is still found in the Canadian constitution where it appears numerous times; however, it is largely a vestige of the past, as the Canadian government does not actively use it (see Canada section). The term "realm" does not appear in the Canadian constitution. Present-day general usage prefers the term realm because it includes the United Kingdom as well, emphasising equality, and no one nation being subordinate to any other. Dominion, however, as a title, technically remains a term that can be used in reference those self-governing countries within the Commonwealth of Nations, other than the United Kingdom itself, that share the same person as monarch.

The generic language of dominion, however, did not cease in relation to the Sovereign. It was, and is, used to describe territories in which the Monarch exercises her sovereignty. The phrase Her Majesty's dominions being a legal and constitutional term that refers to all the realms and territories of the Sovereign, whether independent or not. Thus, for example, the British Ireland Act, 1949 recognised that the Republic of Ireland had "ceased to be part of His Majesty’s dominions." When dependent territories that had never been annexed (that is, were not colonies of the Crown), but were protectorates or trust territories (of the United Nations) were granted independence, the United Kingdom act granting independence always declared that such and such a territory "shall form part of Her Majesty’s dominions"; become part of the territory in which the Queen exercises sovereignty, not merely suzerainty.

Many distinctive characteristics that once pertained only to Dominions are now shared by other states in the Commonwealth, whether republics, independent realms, self-governing colonies or Crown colonies. Even in a historical sense the differences between self-governing colonies and Dominions have often been formal rather than substantial.

See also

Notes

- ^ Merriam Webster's Online Dictionary (based on Collegiate vol., 11th ed.) 2006. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- ^ Hillmer, Norman (2001). "Commonwealth". Toronto: Canadian Encyclopedia. http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0001798. "... the Dominions (a term applied to Canada in 1867 and used from 1907 to 1948 to describe the empire's other self-governing members)"

- ^ Cyprus (Annexation) Order in Council, 1914, dated 5 November 1914.

- ^ The Laws in Wales Act 1535 applies to the Dominion, Principality and Country of Wales

- ^ "Parliamentary questions, Hansard, 5 November 1934". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. 1934-11-05. http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1934/nov/05/wales-title-of-dominion. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Roberts, J.M; The Penguin History of the World; Penguin Books; London; 1995; p. 777; ISBN 357910864

- ^ League of Nations (1924). The Covenant of the League of Nations. Article 1: The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/leagcov.asp. Retrieved 20 April 2009

- ^ Crawford, James (1979). The Creation of States in International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0199228423.

- ^ "Dominion". Youth Encyclopedia of Canada (based on Canadian Encyclopedia). Historica Foundation of Canada, 2008. Accessed 20 June 2008. "The word "Dominion" is the official status of Canada. ... The term is little used today."

- ^ National Health Service Act 2006 (c. 41), sch. 22

- ^ Link to the Australian Constitutions Act 1850 on the website of the National Archives of Australia: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the New South Wales Constitution Act 1855, on the Web site of the National Archives of Australia: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the Victoria Constitution Act 1855, on the Web site of the National Archives of Australia:Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the Constitution Act 1855 (SA), on the Web site of the National Archives of Australia: Foundingsdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the Constitution Act 185 (Tasmania), on the Web site of the National Archives of Australia: Foundingsdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the Constitution Act 1890, which established self-government in Western Australia: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the Order in Council of 6 June 1859, which established the Colony of Queensland, on the Web site of the National Archives of Australia: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the "Letters Patent annexing the Northern Territory to South Australia, 1863" on the Web site of the Australian National Archives: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ Link to the Northern Territory Acceptance Act 1910 (Cth), which transferred the Northern Territory from South Australia to Federal government, on the Web Site of the Australian National Archives: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ "The London Conference December 1866 – March 1867". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/webarchives/20061122121516/http://www.lac-bac.gc.ca/confederation/023001-2085-e.html. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ a b c d Andrew Heard (2008-02-05). "Canadian Independence". http://www.sfu.ca/~aheard/324/Independence.html.

- ^ a b Eugene Forsey (2007-10-14). "How Canadians Govern Themselves". http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/library/idb/forsey/parl_gov_01-e.asp.

- ^ F. R. Scott (January 1944). "The End of Dominion Status". The American Journal of International Law (American Society of International Law) 38 (1): 34–49. doi:10.2307/2192530. JSTOR 2192530.

- ^ B.Hunter (ed), The Stateman's Year Book 1996-1997, Macmillan Press Ltd, pp.130-156

- ^ Order in Council of the UK Privy Council, 6 June 1859, establishing responsible government in Queensland. See Australian Government's "Documenting a Democracy" website at this webpage: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ Constitution Act 1890 (UK), which came into effect as the Constitution of Western Australia when proclaimed in WA on 21 October 1890, and establishing responsible government in WA from that date; Australian Government's "Documenting a Democracy" website: Foundingdocs.gov.au

- ^ D.Smith, Head of State, MaCleay Press 2005, p.18

- ^ D.Smith, Head of State, MaCleay Press 2005, p.102

- ^ Scott, Frank R. (January 1944). "The End of Dominion Status". The American Journal of International Law (American Society of International Law) 38 (1): 34–49. doi:10.2307/2192530. http://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/ajil38&div=8&id=&page=.

- ^ "National Flag of Canada Day: How Did You Do?". Department of Canadian Heritage. http://www.pch.gc.ca/special/flag-drapeau/defi-challenge/reponses-answers_e.cfm. Retrieved 2008-02-07. "The issue of our country's legal title was one of the few points on which our constitution is not entirely homemade. The Fathers of Confederation wanted to call the country “the Kingdom of Canada”. However the British government was afraid of offending the Americans so it insisted on the Fathers finding another title. The term “Dominion” was drawn from Psalm 72. In the realms of political terminology, the term dominion can be directly attributed to the Fathers of Confederation and it is one of the very few, distinctively Canadian contributions in this area. It remains our country's official title."

- ^ "The Prince of Wales 2001 Royal Visit: April 25 - April 30; Test Your Royal Skills". Department of Canadian Heritage. 2001. http://www.canadianheritage.gc.ca/special/royalvisit/royal-quiz-answers.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-07. "As dictated by the British North America Act, 1867, the title is Dominion of Canada. The term is a uniquely Canadian one, implying independence and not colonial status, and was developed as a tribute to the Monarchical principle at the time of Confederation."

- ^ "How Canadians Govern Themselves". PDF. http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/library/idb/forsey/PDFs/How_Canadians_Govern_Themselves-6ed.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-06. Forsey, Eugene (2005). How Canadians Govern Themselves (6th ed.). Ottawa: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. ISBN 0-662-39689-8. "The two small points on which our constitution is not entirely homemade are, first, the legal title of our country, “Dominion,” and, second, the provisions for breaking a deadlock between the Senate and the House of Commons."

- ^ J. E. Hodgetts. 2004. "Dominion". Oxford Companion to Canadian History, Gerald Hallowell, ed.(ISBN 0-19-541559-0) p. 183: "... Ironically, defenders of the title dominion who see signs of creeping republicanism in such changes can take comfort in the knowledge that the Constitution Act, 1982, retains the title and requires a constitutional amendment to alter it."

- ^ a b The Statesman's Year Book, p.635

- ^ The Statesman's Year Book, p.1002

- ^ On 7 December 1922 (the day after the establishment of the Irish Free State) the Parliament resolved to make the following address to the King so as to opt out of the Irish Free State: ”MOST GRACIOUS SOVEREIGN, We, your Majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the Senators and Commons of Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled, having learnt of the passing of the Irish Free State Constitution Act, 1922, being the Act of Parliament for the ratification of the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, do, by this humble Address, pray your Majesty that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland". Source: Northern Ireland Parliamentary Report, 7 December 1922 and Anglo-Irish Treaty, sections 11, 12

- ^ The Statesman's Year Book, p.302

- ^ The Statesman's Year Book, p.303

- ^ The Statesman's Year Book

- ^ "History, Constitutional - The Legislative Authority of the New Zealand Parliament - 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 2009-04-22. http://www.teara.govt.nz/1966/H/HistoryConstitutional/TheLegislativeAuthorityOfTheNewZealand/en. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ a b "Dominion status". NZHistory. http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/politics/dominion-status. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Axel Tschentscher, LL.M.. "ICL - New Zealand - Constitution Act 1986". Servat.unibe.ch. http://servat.unibe.ch/icl/nz00000_.html. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ The Stateman’s Year Book p.1156

- ^ Wikisource: South Africa Act 1909

- ^ Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 (Act No. 56 of 1942). The long title for the Act was "To remove Doubts as to the Validity of certain Commonwealth Legislation, to obviate Delays occurring in its Passage, and to effect certain related purposes, by adopting certain Sections of the Statute of Westminster, 1931, as from the Commencement of the War between His Majesty the King and Germany." Link: Foundingdocs.gov.au

References

- Choudry, Sujit. 2001(?). "Constitution Acts" (based on looseleaf by Hogg, Peter W.). Constitutional Keywords. University of Alberta, Centre for Constitutional Studies: Edmonton.

- Holland, R.F., Britain and the Commonwealth Alliance 1918-1939, MacMillan, 1981

- Forsey, Eugene A. 2005. How Canadians Govern Themselves, 6th ed. (ISBN 0-662-39689-8) Canada: Ottawa.

- Hallowell, Gerald, ed. 2004. The Oxford Companion to Canadian History. (ISBN 0-19-541559-0) Oxford University Press: Toronto; p. 183-4.

- Marsh, James H., ed. 1988. "Dominion" et al. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Hurtig Publishers: Toronto.

- Martin, Robert. 1993(?). 1993 Eugene Forsey Memorial Lecture: A Lament for British North America. The Machray Review. Prayer Book Society of Canada.—A summative piece about nomenclature and pertinent history with abundant references.

- Rayburn, Alan. 2001. Naming Canada: stories about Canadian place names, 2nd ed. (ISBN 0-8020-8293-9) University of Toronto Press: Toronto.

British Empire and Commonwealth of Nations Legend

Current territory · Former territory

* now a Commonwealth realm · now a member of the Commonwealth of NationsEurope18th century

1708–1757 Minorca

since 1713 Gibraltar

1763–1782 Minorca

1798–1802 Minorca19th century

1800–1964 Malta

1807–1890 Heligoland

1809–1864 Ionian Islands20th century

1921-1937 Irish Free StateNorth America17th century

1583–1907 Newfoundland

1607–1776 Virginia

since 1619 Bermuda

1620–1691 Plymouth Colony

1629–1691 Massachusetts Bay Colony

1632–1776 Maryland

1636–1776 Connecticut

1636–1776 Rhode Island

1637–1662 New Haven Colony

1663–1712 Carolina

1664–1776 New York

1665–1674 and 1702-1776 New Jersey

1670–1870 Rupert's Land

1674–1702 East Jersey

1674–1702 West Jersey

1680–1776 New Hampshire

1681–1776 Pennsylvania

1686–1689 Dominion of New England

1691–1776 Massachusetts18th century

1701–1776 Delaware

1712–1776 North Carolina

1712–1776 South Carolina

1713–1867 Nova Scotia

1733–1776 Georgia

1763–1873 Prince Edward Island

1763–1791 Quebec

1763–1783 East Florida

1763–1783 West Florida

1784–1867 New Brunswick

1791–1841 Lower Canada

1791–1841 Upper Canada19th century

1818–1846 Columbia District / Oregon Country1

1841–1867 Province of Canada

1849–1866 Vancouver Island

1853–1863 Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands

1858–1866 British Columbia

1859–1870 North-Western Territory

1862–1863 Stikine Territory

1866–1871 Vancouver Island and British Columbia

1867–1931 *Dominion of Canada2

20th century

1907–1949 Dominion of Newfoundland31Occupied jointly with the United States

2In 1931, Canada and other British dominions obtained self-government through the Statute of Westminster. see Canada's name.

3Gave up self-rule in 1934, but remained a de jure Dominion until it joined Canada in 1949.Latin America and the Caribbean17th century

1605–1979 *Saint Lucia

1623–1883 Saint Kitts (*Saint Kitts & Nevis)

1624–1966 *Barbados

1625–1650 Saint Croix

1627–1979 *St. Vincent and the Grenadines

1628–1883 Nevis (*Saint Kitts & Nevis)

1629–1641 St. Andrew and Providence Islands4

since 1632 Montserrat

1632–1860 Antigua (*Antigua & Barbuda)

1643–1860 Bay Islands

since 1650 Anguilla

1651–1667 Willoughbyland (Suriname)

1655–1850 Mosquito Coast (protectorate)

1655–1962 *Jamaica

since 1666 British Virgin Islands

since 1670 Cayman Islands

1670–1973 *Bahamas

1670–1688 St. Andrew and Providence Islands4

1671–1816 Leeward Islands

18th century

1762–1974 *Grenada

1763–1978 Dominica

since 1799 Turks and Caicos Islands19th century

1831–1966 British Guiana (Guyana)

1833–1960 Windward Islands

1833–1960 Leeward Islands

1860–1981 *Antigua and Barbuda

1871–1964 British Honduras (*Belize)

1882–1983 *Saint Kitts.2C 1623 to 1700|St. Kitts and Nevis

1889–1962 Trinidad and Tobago

20th century

1958–1962 West Indies Federation4Now the San Andrés y Providencia Department of Colombia

AfricaAsiaOceania18th century

1788–1901 New South Wales19th century

1803–1901 Van Diemen's Land/Tasmania

1807–1863 Auckland Islands7

1824–1980 New Hebrides (Vanuatu)

1824–1901 Queensland

1829–1901 Swan River Colony/Western Australia

1836–1901 South Australia

since 1838 Pitcairn Islands

1841–1907 Colony of New Zealand

1851–1901 Victoria

1874–1970 Fiji8

1877–1976 British Western Pacific Territories

1884–1949 Territory of Papua

1888–1965 Cook Islands7

1889–1948 Union Islands (Tokelau)7

1892–1979 Gilbert and Ellice Islands9

1893–1978 British Solomon Islands1020th century

1900–1970 Tonga (protected state)

1900–1974 Niue7

1901–1942 *Commonwealth of Australia

1907–1953 *Dominion of New Zealand

1919–1942 Nauru

1945–1968 Nauru

1919–1949 Territory of New Guinea

1949–1975 Territory of Papua and New Guinea117Now part of the *Realm of New Zealand

8Suspended member

9Now Kiribati and *Tuvalu

10Now the *Solomon Islands

11Now *Papua New GuineaAntarctica and South Atlantic17th century

since 1659 St. Helena1219th century

since 1815 Ascension Island12

since 1816 Tristan da Cunha12

since 1833 Falkland Islands1320th century

since 1908 British Antarctic Territory14

since 1908 South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands13, 1412Since 2009 part of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; Ascension Island (1922—) and Tristan da Cunha (1938—) were previously dependencies of St Helena

13Occupied by Argentina during the Falklands War of April–June 1982

14Both claimed in 1908; territories formed in 1962 (British Antarctic Territory) and 1985 (South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands)Categories:- British Empire

- Commonwealth realms

- Governance of the British Empire

- Legal history of Canada

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.