- Okun's law

-

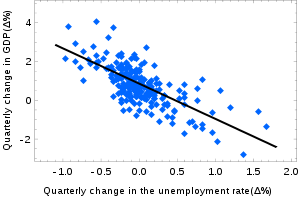

In economics, Okun's law is an empirically observed relationship relating unemployment to losses in a country's production first quantified by Arthur M. Okun. The "gap version" states that for every 1% increase in the unemployment rate, a country's GDP will be at an additional roughly 2% lower than its potential GDP. The "difference version" [1] describes the relationship between quarterly changes in unemployment and quarterly changes in real GDP. The accuracy of the law has been disputed. The name refers to economist Arthur Okun who proposed the relationship in 1962.[2]

Contents

Imperfect relationship

Okun's law is more accurately called "Okun's rule of thumb" because it is primarily an empirical observation rather than a result derived from theory. Okun's law is approximate because factors other than employment (such as productivity) affect output. In Okun's original statement of his law, a 3% increase in output corresponds to a 1% decline in the rate of unemployment; a .5% increase in labor force participation; a .5% increase in hours worked per employee; and a 1 % increase in output per hours worked (labor productivity).[3]

Okun's law states that a one point increase in the unemployment rate is associated with two percentage points of negative growth in real GDP. The relationship varies depending on the country and time period under consideration.

The relationship has been tested by regressing GDP or GNP growth on change in the unemployment rate. Martin Prachowny estimated about a 3% decrease in output for every 1% increase in the unemployment rate (Prachowny 1993). The magnitude of the decrease seems to be declining over time in the United States. According to Andrew Abel and Ben Bernanke, estimates based on data from more recent years give about a 2% decrease in output for every 1% increase in unemployment (Abel and Bernanke, 2005).

There are several reasons why GDP may increase or decrease more rapidly than unemployment decreases or increases. As unemployment increases,

- a reduction in the multiplier effect created by the circulation of money from employees

- unemployed persons may drop out of the labor force (stop seeking work), after which they are no longer counted in unemployment statistics

- employed workers may work shorter hours

- labor productivity may decrease, perhaps because employers retain more workers than they need

One implication of Okun's law is that an increase in labor productivity or an increase in the size of the labor force can mean that real net output grows without net unemployment rates falling (the phenomenon of "jobless growth").[4]

Mathematical statements

The gap version of Okun's law may be written (Abel & Bernanke 2005) as:

, where:

, where:

is potential output or GDP at full-employment

is potential output or GDP at full-employment- Y is actual output

is the natural rate of unemployment

is the natural rate of unemployment- u is actual unemployment rate

- c is the factor relating changes in unemployment to changes in output

In the United States since 1955 or so, the value of c has typically been around 2 or 3, as explained above.

The gap version of Okun's law, as shown above, is difficult to use in practice because

and

and  can only be estimated, not measured. A more commonly used form of Okun's law, known as the difference or growth rate form of Okun's law, relates changes in output to changes in unemployment:

can only be estimated, not measured. A more commonly used form of Okun's law, known as the difference or growth rate form of Okun's law, relates changes in output to changes in unemployment: , where:

, where:

- Y and c are as defined above

- ΔY is the change in actual output from one year to the next

- Δu is the change in actual unemployment from one year to the next

- k is the average annual growth rate of full-employment output

At the present time in the United States, k is about 3% and c is about 2, so the equation may be written

The graph at the top of this article illustrates the growth rate form of Okun's law, measured quarterly rather than annually.

Derivation of the growth rate form of Okun's law

We start with the first form of Okun's law:

Taking annual differences on both sides, we obtain

Putting both numerators over a common denominator, we obtain

Multiplying the left hand side by

, which is approximately equal to 1, we obtain

, which is approximately equal to 1, we obtainWe assume that

, the change in the natural rate of unemployment, is approximately equal to 0. We also assume that

, the change in the natural rate of unemployment, is approximately equal to 0. We also assume that  , the growth rate of full-employment output, is approximately equal to its average value, k. So we finally obtain

, the growth rate of full-employment output, is approximately equal to its average value, k. So we finally obtainNotes

References

- Abel, Andrew B. & Bernanke, Ben S. (2005). Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Pearson Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-321-16212-9.

- Baily, Martin Neil & Okun, Arthur M. (1965) The Battle Against Unemployment and Inflation: Problems of the Modern Economy. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.; ISBN 0393950557 (1983; 3rd revised edition).

- , Prueba de Causalidad y Determinación de la NAIRU, Dr. J F Bellod Redondo.

- Case, Karl E. & Fair, Ray C. (1999). Principles of Economics (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-961905-4.

- Knotek, Edward S. "How Useful Is Okun's Law." Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Fourth Quarter 2007, pages 73–103.

- Prachowny, Martin F. J. (1993). "Okun's Law: Theoretical Foundations and Revised Estimates," The Review of Economics and Statistics, 75(2), p p. 331-336.

- Gordon, Robert J., Productivity, Growth, Inflation and Unemployment, Cambridge University Press, 2004

- McBride, Bill. "Real GDP Growth and the Unemployment Rate." Calculated Risk. 11 Oct. 2010. Web. 05 Dec. 2010. <http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2010/10/real-gdp-growth-and-unemployment-rate.html>.

Categories:- Economics laws

- Rules of thumb

- Unemployment

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.