- Dodona's Grove

-

Dodona's Grove (1640) is a historical allegory by James Howell, making extensive use of tree lore.[1]

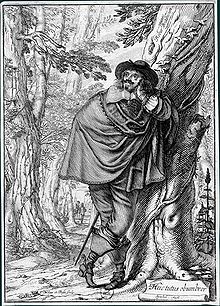

James Howell from Dodona's Grove (1641)

by Abraham BosseContents

Description

This curiosity purports to be a history of Europe since the accession of James I of England put into an allegorical form in which the roles of the various Kings, princes and nobles are taken by various trees. Its effect, however is not quite what that would imply, as the tree-allegory remains on the level of the emblem, whereas the action demands if not people, then at least anthropomorphs convincingly capable of some sort of agency. Before the book is properly underway there is already a tension between its tenor and supposed vehicle. Having set up an allegorical apparatus, with a comprehensive Clavis, or key of the significance of the various names which he uses, as well as illustrations of the various trees, the text itself, though conforming vaguely to an allegorical mode, is anything but smooth in its allegorical workings, anything but subtle in its jarring clashes of style and treatment, which take it far away from earlier, more consistently executed examples of the genre.

Publication

In England at the time of the publication of Dodona's Grove, the dominant paradigm for the writing of allegorical romance, particularly when of a political nature was John Barclay's Argenis, a work which told the story of the religious conflict in France under Henry III and IV. Both of the dedicatory poems which precede Dodona's Grove mention the volume, and indeed there are similarities between Barclay and Howell in their attitudes towards writing, but what they have to say equally points up their differences. In Barclay, the process is much more subtle, more comprehensively articulated as an allegory which is inclusive of all its aspects. Instead of putting forward any kind of manifesto himself, he lets one of the characters in the romance tell of "a new form of writing", which he intends to invent, and thus places the text's genesis within its own fictional space:

- ... I will compile some stately fable in manner of a history: in it will I fold vp strange events and mingle together arms, marriages, bloodshed, mirth with many and various successes... And that they may not say, they are traduced, no mans Character shall be simply set down: I shall find many things to conceal them, which would not agree with them if they were made knowne. I know the disposition of our countrey-men: because I seem to tell them tales, I shall haue them all. While they read, while they are affected with anger or favour, as it were against strangers, they shall meete with themselves; and find in the glass held before them, the shew and merit of their own fame. For, I that binde not myselfe religiously to the writing of a true History, may take this liberty.

Historical form

Like Barclay, Howell eschews conventional historical form, but the earlier writer's subtle combination of raison d'etat and moral considerations are quite distinct from Howell's intentions, or rather what he would like us to believe those intentions are. He writes as he does on the authority of the ancients, rather than political expedients he claims:

- Nor is the Author the first, though the first in this peculiar Mayden fancy, who deeming it a flat and vulgar task to compile a plain and downright story, which consists meerely of collections, and is as easie as walking horses or gleaning of corn hath under heiroglyphicks, allegories and emblems endeavour'd to diversifie and enrich the matter, to embroder it up and down with Apologs, Essays, Parables, and other flourishes; for we find this to be the ancient'st and most ingenious way of delivering truth, and transmitting it to posterity: Omnis fabula fundatur in Historia.

Styles

Epistemologically, therefore, what Howell will admit as truth is a broad spectrum of styles, and their heterogeneous nature, rather than undermining his viewpoint, confirms it in that the various styles that he uses do indeed clash with one another, demonstrating themselves as corollaries of the elemental conflicts in the extra-textual world, and upon which, as a neo-Stoic, he believed that world was based. This shall be discussed further below.

On a first reading, these clashing registers of discourse are particularly noticeable; set uncomfortably with the parergon of the allegory, the text's main framework, sit a variety of discourses: an exposition of the various lands of Europe strides the topoi and genres of travel narrative in the first section, whilst later, diplomatic history and the romance ideal chafe against one another when Prince Charles' visit to Spain is dealt with.

Main subject

The book's purported main subject, that of history, is often drowned out in the surface noise of the competing discourses in which it is expressed. The pulling of the text between narrative strategies, and between systems of mythology, medicine and philosophy can be arresting, and sometimes annoying, but these are disjunctions which are meant to be there, and the clashes and shifts in register which we see in this work are most probably intentional. Whether this makes good or bad historiography is another matter, and one I do not propose to investigate here. In this case, the results are not important in terms of success or failure, but in terms of their invention.

Rhetorical Structure

The rhetorical form of Dodona's Grove is based on a series of frames, and a series of concomitant modes. Within its allegorical world of trees, the book has two main frames: that of the syncretic Stuart myth, which fuses elements of Greek, Roman and ancient British myth with hermetic neoplatonism, and that of a specific view of Galenic medicine, altered by an interest in neo-Stoical philosophy to be a radically unstable phenomenon. In these two clashing frameworks must exist the various modes in which the events are narrated: travel narrative, romance, diplomatic report, encomium, and medical treatise.

See also

- Pembroke, William Herbert of Swansea

- Dodona — The place in Greece, the myth and the Oracle.

External links

- From The Abraham Cowley Text and Image Archive

- The Hywel dda (Howell the Good) garden at Whitland with an explanation of the Law and trees in 10th century Wales

- http://www.calvin.edu/academic/clas/pathways/dodona/ninf.htm

References

Categories:- English books

- 1640 books

- Allegory

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.