- Orientalism (book)

-

Orientalism

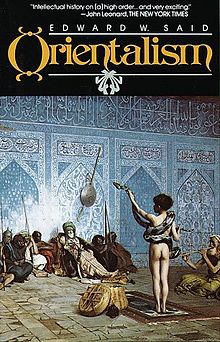

Author(s) Edward Said Country United States Language English Subject(s) Postcolonial studies Genre(s) Non-fiction Publisher Vintage Books Publication date 1978 Media type Print (Paperback) ISBN ISBN 0-394-74067-X OCLC Number 4831769 Dewey Decimal 950/.07/2 LC Classification DS12 .S24 1979 Orientalism is a book published in 1978 by Edward Said that has been highly influential and controversial in postcolonial studies and other fields. In the book, Said effectively redefined the term "Orientalism" to mean a constellation of false assumptions underlying Western attitudes toward the Middle East. This body of scholarship is marked by a "subtle and persistent Eurocentric prejudice against Arabo-Islamic peoples and their culture." He argued that a long tradition of romanticized images of Asia and the Middle East in Western culture had served as an implicit justification for European and American colonial and imperial ambitions. Just as fiercely, he denounced the practice of Arab elites who internalized the US and British orientalists' ideas of Arabic culture.

So far as the United States seems to be concerned, it is only a slight overstatement to say that Muslims and Arabs are essentially seen as either oil suppliers or potential terrorists. Very little of the detail, the human density, the passion of Arab-Moslem life has entered the awareness of even those people whose profession it is to report the Arab world. What we have instead is a series of crude, essentialized caricatures of the Islamic world presented in such a way as to make that world vulnerable to military aggression.[1]—Edward Said, The NationContents

Overview

Said summarised his work in these terms:

- My contention is that Orientalism is fundamentally a political doctrine willed over the Orient because the Orient was weaker than the West, which elided the Orient’s difference with its weakness....As a cultural apparatus Orientalism is all aggression, activity, judgment, will-to-truth, and knowledge (Orientalism, p. 204).

Said also wrote:

- My whole point about this system is not that it is a misrepresentation of some Oriental essence — in which I do not for a moment believe — but that it operates as representations usually do, for a purpose, according to a tendency, in a specific historical, intellectual, and even economic setting (p. 273).

Principally a study of 19th-century literary discourse and strongly influenced by the work of thinkers like Chomsky, Foucault and Gramsci, Said's work also engages contemporary realities and has clear political implications as well. Orientalism is often classed with postmodernist and postcolonial works that share various degrees of skepticism about representation itself (although a few months before he died, Said said he considers the book to be in the tradition of "humanistic critique" and the Enlightenment[2]).

A central idea of Orientalism is that Western knowledge about the East is not generated from facts or reality, but from preconceived archetypes that envision all "Eastern" societies as fundamentally similar to one another, and fundamentally dissimilar to "Western" societies. This discourse establishes "the East" as antithetical to "the West". Such Eastern knowledge is constructed with literary texts and historical records that often are of limited understanding of the facts of life in the Middle East.[3]

Following the ideas of Michel Foucault, Said emphasized the relationship between power and knowledge in scholarly and popular thinking, in particular regarding European views of the Islamic Arab world. Said argued that Orient and Occident worked as oppositional terms, so that the "Orient" was constructed as a negative inversion of Western culture. The work of another thinker, Antonio Gramsci, was also important in shaping Edward Said's analysis in this area. In particular, Said can be seen to have been influenced by Gramsci's notion of hegemony in understanding the pervasiveness of Orientalist constructs and representations in Western scholarship and reporting, and their relation to the exercise of power over the "Orient".[4]

Although Edward Said limited his discussion to academic study of Middle Eastern, African and Asian history and culture, he asserted that "Orientalism is, and does not merely represent, a significant dimension of modern political and intellectual culture." (p. 12) Said's discussion of academic Orientalism is almost entirely limited to late 19th and early 20th century scholarship. Most academic Area Studies departments had already abandoned an imperialist or colonialist paradigm of scholarship. He names the work of Bernard Lewis as an example of the continued existence of this paradigm, but acknowledges that it was already somewhat of an exception by the time of his writing (1977). The idea of an "Orient" is a crucial aspect of attempts to define "the West". Thus, histories of the Greco–Persian Wars may contrast the monarchical government of the Persian Empire with the democratic tradition of Athens, as a way to make a more general comparison between the Greeks and the Persians, and between "the West" and "the East", or "Europe" and "Asia", but make no mention of the other Greek city states, most of which were not ruled democratically.

Taking a comparative and historical literary review of European, mainly British and French, scholars and writers looking at, thinking about, talking about, and writing about the peoples of the Middle East, Said sought to lay bare the relations of power between the colonizer and the colonized in those texts. Said's writings have had far-reaching implications beyond area studies in Middle East, to studies of imperialist Western attitudes to India, China and elsewhere. It was one of the foundational texts of postcolonial studies. Said later developed and modified his ideas in his book Culture and Imperialism (1993).

Many scholars now use Said's work to attempt to overturn long-held, often taken-for-granted Western ideological biases regarding non-Westerners in scholarly thought. Some post-colonial scholars would even say that the West's idea of itself was constructed largely by saying what others were not. If "Europe" evolved out of "Christendom" as the "not-Byzantium", early modern Europe in the late 16th century (see Battle of Lepanto (1571)) defined itself as the "not-Turkey."

Said puts forward several definitions of "Orientalism" in the introduction to Orientalism. Some of these have been more widely quoted and influential than others:[citation needed]

- "A way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the Orient's special place in European Western experience." (p. 1)

- "a style of thought based upon an ontological and epistemological distinction made between the Orient' and (most of the time) 'the Occident'." (p. 2)

- "A Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient." (p. 3)

- "...particularly valuable as a sign of European-Atlantic power over the Orient than it is as a veridic discourse about the Orient." (p. 6)

- "A distribution of geopolitical awareness into aesthetic, scholarly, economic, sociological, historical, and philological texts." (p. 12)

In his preface to the 2003 edition of Orientalism, Said also warned against the "falsely unifying rubrics that invent collective identities," citing such terms as "America", "The West", and "Islam", which were leading to what he felt was a manufactured "clash of civilisations."

The book by chapter

The book is divided into three chapters:

- The Scope of Orientalism

- Orientalist Structures and Restructures

- Orientalism Now

Chapter 1: The Scope of Orientalism

In this section Said outlines his argument with several caveats as to how it may be flawed. He states that it fails to include Russian Orientalism and explicitly excludes German Orientalism, which he suggests had "clean" pasts (Said 1978: 2&4), and could be promising future studies. Said also suggests that not all academic discourse in the West has to be Orientalist in its intent but much of it is. He also suggests that all cultures have a view of other cultures that may be exotic and harmless to some extent, but it is not this view that he argues against and when this view is taken by a militarily and economically dominant culture against another it can lead to disastrous results.

Said draws on written and spoken historical commentary by such Western figures as Arthur James Balfour, Napoleon, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Byron, Henry Kissinger, Dante and others who all portray the "East" as being both "other" and "inferior."

He also draws on several European studies of the region by Orientalists including the Bibliotheque Orientale by French author Barthélemy d'Herbelot de Molainville to illustrate the depth of Orientalist discourse in European society and in their academic, literary and political interiors.

One apt representation Said gives is a poem by Victor Hugo titled "Lui" written for Napoleon:

By the Nile I find him once again.

Egypt shines with the fires of his dawn;

His imperial orb rises in the Orient.Victor, enthusiast, bursting with achievements,

Prodigious, he stunned the land of prodigies.

The old sheikhs venerated the young and prudent emir.

The people dreaded his unprecedented arms;

Sublime, he appeared to the dazzled tribes

Like a Mahomet of the Occident. (Orientalism pg. 83)Chapter 2: Orientalist Structures and Restructures

Harem Pool by the Orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme c. 1876 (he also painted the cover illustration above); naked females in harem or bathing settings are a staple of much Orientalist painting, although this is not a subject covered by Said himself.

Harem Pool by the Orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme c. 1876 (he also painted the cover illustration above); naked females in harem or bathing settings are a staple of much Orientalist painting, although this is not a subject covered by Said himself.

In this chapter Said outlines how Orientalist discourse was transferred from country to country and from political leader to author. He suggests that this discourse was set up as a foundation for all (or most all) further study and discourse of the Orient by the Occident.

He states that: "The four elements I have described - expansion, historical confrontation, sympathy, classification - are the currents in eighteenth-century thought on whose presence the specific intellectual and institutional structures of modern Orientalism depend” (120).

Drawing heavily on 19th century European exploration by such historical figures as Sir Richard Francis Burton and Chateaubriand, Said suggests that this new discourse about the Orient was situated within the old one. Authors and scholars such as Edward William Lane, who spent only two to three years in Egypt but came back with an entire book about them (Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians) which was widely circulated in Europe.

Further travelers and academics of the East depended on this discourse for their own education, and so the Orientalist discourse of the West over the East was passed down through European writers and politicians (and therefore through all Europe).

Chapter 3: Orientalism Now

This chapter outlines where Orientalism has gone since the historical framework Said outlined in previous chapters. The book was written in 1978 and so only covers historical occurrences that happened up to that date.

It is in this chapter that Said makes his overall statement about cultural discourse: "How does one represent other cultures? What is another culture? Is the notion of a distinct culture (or race, or religion, or civilization) a useful one, or does it always get involved either in self-congratulation (when one discusses one's own) or hostility and aggression (when one discusses the 'other')?" (325).

While there is much criticism centered on Said's book, the author himself repeatedly admits his study's shortcomings in this chapter, chapter 1 and in his introduction

Influence

Orientalism is considered to be Edward Said's most influential work and has been translated into at least 36 languages. It has been the focus of any number of controversies and polemics, notably with Bernard Lewis, whose work is critiqued in the book's final section, entitled "Orientalism Now: The Latest Phase." In October 2003, one month after Said died, a commentator wrote in a Lebanese newspaper that through Orientalism "Said's critics agree with his admirers that he has single-handedly effected a revolution in Middle Eastern studies in the U.S." He cited a critic who claimed since the publication of Orientalism "U.S. Middle Eastern Studies were taken over by Edward Said's postcolonial studies paradigm" (Daily Star, October 20, 2003). Even those who contest its conclusions and criticize its scholarship, like George P. Landow of Brown University, call it "a major work."[5] The Belgian-born American literary critic Paul De Man supported Said's criticism of such modern scholars, as he stated in his article on semiotic rhetoric: "Said took a step further than any other modern scholar of his time, something I dare not do. I remain in the safety of rhetorical analysis where criticism is the second best thing I do."[6]

However, Orientalism was not the first to produce of Western knowledge of the Orient and of Western scholarship: "Abd-al-Rahman al Jabarti, the Egyptian chronicler and a witness to Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, for example, had no doubt that the expedition was as much an epistemological as military conquest."[7] Even in recent times (1963, 1969 & 1987) the writings and research of V. G. Kiernan, Bernard S. Cohn and Anwar Abdel Malek traced the relations between European rule and representations.[8]

Nevertheless, Orientalism is cited as a detailed and influential work within the study of Orientalism. Anthropologist Talal Asad argued that Orientalism is “not only a catalogue of Western prejudices about and misrepresentations of Arabs and Muslims”,[9] but more so an investigation and analysis of the "authoritative structure of Orientalist discourse – the closed, self-evident, self-confirming character of that distinctive discourse which is reproduced again and again through scholarly texts, travelogues, literary works of imagination, and the obiter dicta of public men [and women] of affairs."[9] Indeed, the book describes how "the hallowed image of the Orientalist as an austere figure unconcerned with the world and immersed in the mystery of foreign scripts and languages has acquired a dark hue as the murky business of ruling other peoples now forms the essential and enabling background of his or her scholarship."[10]

Said does not include Orientalist painting or other visual art in his survey, despite the example on the book's cover, but other writers, notably Linda Nochlin, have extended his analysis to cover it, "with uneven results".[11]

Criticism

Critics of Said's theory, such as the historian Bernard Lewis, argue that Said's account contains many factual, methodological and conceptual errors. Said ignores many genuine contributions to the study of Eastern cultures made by Westerners during the Enlightenment and Victorian eras. Said's theory does not explain why the French and English pursued the study of Islam in the 16th and 17th centuries, long before they had any control or hope of control in the Middle East. Critics[who?] have argued that Said ignored the contributions of Italian, Dutch, and particularly the massive contribution of German scholars (Said himself addressed and acknowledged the deficit of German academic scholarship in the book's introduction). Lewis claims that the scholarship of these nations was more important to European Orientalism than the French or British, but the countries in question either had no colonial projects in the Mideast (Dutch and Germans), or no connection between their Orientalist research and their colonialism (Italians). Said's theory also does not explain why much of Orientalist study did nothing to advance the cause of imperialism.

As Lewis asks,

What imperial purpose was served by deciphering the ancient Egyptian language, for example, and then restoring to the Egyptians knowledge of and pride in their forgotten, ancient past?[12]Lewis argued that Orientalism arose from humanism, which was distinct from Imperialist ideology, and sometimes in opposition to it. Orientalist study of Islam arose from the rejection of religious dogma, and was an important spur to discovery of alternative cultures. Lewis criticised as "intellectual protectionism" the argument that only those within a culture could usefully discuss it.[13]

In his rebuttal to Lewis, Said stated that Lewis's negative rejoinder must be placed into its proper context. Since one of Said's principal arguments is that Orientalism was used (wittingly or unwittingly) as an instrument of empire, he contends that Lewis' critique of this thesis could hardly be judged in the disinterested, scholarly light that Lewis would like to present himself, but must be understood in the proper knowledge of what Said claimed was Lewis' own (often masked) neo-imperialist proclivities, as displayed by the latter's political or quasi-political appointments and pronouncements.

Bryan Turner critiques Said’s work saying there were a multiplicity of forms and traditions of Orientalism. He is therefore critical of Said’s attempt to try to place them all under the framework of the orientalist tradition.[14] Other critics of Said have argued that while many distortions and fantasies certainly existed, the notion of "the Orient" as a negative mirror image of the West cannot be wholly true because attitudes to distinct cultures diverged significantly.

According to Naji Oueijan, Orientalism manifested in two movements: a genuine one prompted by scholars like Sir William Jones and literary figures such as Samuel Johnson, William Beckford, and Lord Byron; and a false one motivated by religious and political literary propagandists.[15] Another view holds that other cultures are necessarily identified by their "otherness", since otherwise their distinctive characteristics would be invisible, and thus the most striking differences are emphasized in the eyes, and literature, of the outsider.[16] John MacKenzie notes that the Western "dominance" critiqued by Said has often been challenged and answered, for instance in the ‘Subaltern Studies’ body of literature, which strives to give voice to marginalized peoples.[17] Further criticism includes the observation that the criticisms levied by Said at Orientalist scholars of being essentialist can in turn be levied at him for the way in which he writes of the West as a hegemonic mass, stereotyping its characteristics.[18]

Robert Irwin

In his book For Lust of Knowing, British historian Robert Irwin criticizes what he claims to be Said's thesis that throughout Europe’s history, “every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric.” Irwin points out that long before notions like third-worldism and post-colonialism entered academia, many Orientalists were committed advocates for Arab and Islamic political causes.

Goldziher backed the Urabi revolt against foreign control of Egypt. The Cambridge Iranologist Edward Granville Browne became a one-man lobby for Persian liberty during Iran’s constitutional revolution in the early 20th century. Prince Leone Caetani, an Italian Islamicist, opposed his country’s occupation of Libya, for which he was denounced as a “Turk.” And Louis Massignon may have been the first Frenchman to take up the Palestinian Arab cause.[19]

George P. Landow

While acknowledging the great influence of Orientalism on postcolonial theory since its publication in 1978, George P. Landow - a professor of English and Art History at Brown University in the United States - finds Said's scholarship lacking. He chides Said for ignoring the non-Arab Asian countries, non-Western imperialism, the occidentalist ideas that abound in East towards the Western, and gender issues. Orientalism assumes that Western imperialism, Western psychological projection, "and its harmful political consequences are something that only the West does to the East rather than something all societies do to one another." Landow also finds Orientalism's political focus harmful to students of literature since it has led to the political study of literature at the expense of philological, literary, and rhetorical issues [20] (see also the article Edward Said.)

Landow points out that Said completely ignores China, Japan, and South East Asia, in talking of "the East," but then goes on to criticise the West’s homogenisation of the East. Furthermore, Landow states that Said failed to capture the essence of the Middle East, not least by overlooking important works by Egyptian and Arabic scholars.

In addition to poor knowledge about the history of European and non-European imperialism, another of Landow’s criticisms is that Said sees only the influence of the West on the East in colonialism. Landow argues that these influences were not simply one-way, but cross-cultural, and that Said fails to take into account other societies or factors within the East.

He also criticises Said’s "dramatic assertion that no European or American scholar could `know` the Orient." However, in his view what they have actually done constitutes acts of oppression.[21] Moreover, one of the principal claims made by Landow is that Said did not allow the views of other scholars to feature in his analysis; therefore, he committed “the greatest single scholarly sin” in Orientalism.[20]

Bernard Lewis

Orientalism included much criticism of historian Bernard Lewis, which Lewis in turn answered. Said contended that Lewis treats Islam as a monolithic entity without the nuance of its plurality, internal dynamics, and historical complexities, and accused him of "demagogy and downright ignorance."[22] Said quoted Lewis' assertion that "the Western doctrine of the right to resist bad government is alien to Islamic thought". Lewis continued,

In the Arabic-speaking countries a different word was used for [revolution] thawra. The root th-w-r in classical Arabic meant to rise up (e.g. of a camel), to be stirred or excited, and hence, especially in Maghribi usage, to rebel.

Said suggests that this particular passage is "full of condescension and bad faith", that the example of a camel is selected deliberately to debase Arab revolutionary ambitions: "[I]t is this kind of essentialized description that is natural for students and policymakers of the Middle East." Lewis' writings, according to Said, are often "polemical, not scholarly"; Said asserts that Lewis has striven to depict Islam as "an anti-Semitic ideology, not merely a religion".[23]

[Lewis] goes on to proclaim that Islam is an irrational herd or mass phenomenon, ruling Muslims by passions, instincts, and unreflecting hatreds. The whole point of this exposition is to frighten his audience, to make it never yield an inch to Islam. According to Lewis, Islam does not develop, and neither do Muslims; they merely are, and they are to be watched, on account of that pure essence of theirs (according to Lewis), which happens to include a long-standing hatred of Christians and Jews. Lewis everywhere refrains himself from making such inflammatory statements flat out; he always takes care to say that of course the Muslims are not anti-Semitic the way the Nazis were, but their religion can too easily accommodate itself to anti-Semitism and has done so. Similarly with regard to Islam and racism, slavery, and other more or less "Western" evils. The core of Lewis's ideology about Islam is that it never changes, and his whole mission is now to inform conservative segments of the Jewish reading public, and anyone else who cares to listen, that any political, historical, and scholarly account of Muslims must begin and end with the fact that Muslims are Muslims.[23]

Rejecting the view that western scholarship was biased against the Middle East, Lewis responded that Orientalism developed as a facet of European humanism, independently of the past European imperial expansion.[13] He noted the French and English pursued the study of Islam in the 16th and 17th centuries, yet not in an organized way, but long before they had any control or hope of control in the Middle East; and that much of Orientalist study did nothing to advance the cause of imperialism. "What imperial purpose was served by deciphering the ancient Egyptian language, for example, and then restoring to the Egyptians knowledge of and pride in their forgotten, ancient past?"[12]

Daniel Martin Varisco

Another recent critical assessment of "Orientalism" and its reception across disciplines is provided by anthropologist and historian Daniel Martin Varisco in his "Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid" (University of Washington Press, 2007). Using judicious satirical criticism to defuse what has become an acrimonious debate, Varisco surveys the extensive criticism of Said's methodology, including criticism of his use of Foucault and Gramsci, and argues that the politics of polemics needs to be superseded to move academic discussion of real cultures in the region once imagined as an "Orient" beyond the binary blame game. He concludes (p. 304)

The notion of Oriental homogeneity will exist as long as prejudice serves political ends, but to blame the sins of its current use on hegemonic intellectualism mires ongoing mitigation of bad and biased scholarship in an unresolvable polemic of blame. It is time to read beyond "Orientalism."[24]

Ibn Warraq

In his criticism of Orientalism, author Ibn Warraq complains Said's belief that all truth was relative undermined his credibility.

In response to critics who over the years have pointed to errors of fact and detail so mountainous as to destroy his thesis, [Said] finally admitted that he had "no interest in, much less capacity for, showing what the true Orient and Islam really are." [25]

See also

References

- ^ Edward W. Said, "Islam Through Western Eyes," The Nation April 26, 1980, first posted online January 1, 1998, accessed December 13, 2010.

- ^ Orientalism 25 Years Later, by Said in 2003

- ^ Edward Said and The Production of Knowledge, by Sethi,Arjun (University of Maryland) accessed April 20, 2007.

- ^ Zachary Lockman, "Contending Visions of the Middle East: the History and Politics of Orientalism" (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004), p. 205.

- ^ Edward W. Said's Orientalism

- ^ Nosal, K R. American Criticism, New York Standard, New York. 2002

- ^ Prakash, G (Oct., 1995) “Orientalism Now” History and Theory, Vol. 34, No. 3, p 200.

- ^ Prakash, G (Oct., 1995) “Orientalism Now” History and Theory , Vol. 34, No. 3, p 200.

- ^ a b Asad, T (1980)English Historical Review p648

- ^ Prakash, G (Oct., 1995) “Orientalism Now” History and Theory , Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 199-200.

- ^ Tromans, Nicholas, and others, The Lure of the East, British Orientalist Painting, 6, 11 (quoted), 23-25, 2008, Tate Publishing, ISBN 9781854377333

- ^ a b Lewis, Bernard, Islam and the West, Oxford University Press, 1993, p.126

- ^ a b Kramer, Martin (1999). "Bernard Lewis". Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing. Vol. 1. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 719–720. http://www.martinkramer.org/sandbox/reader/archives/bernard-lewis/. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Turner, B.S., 1994, Orientalism, Postmodernism and Globalism, London, Routledge

- ^ The Progress of an Image: The East in English Literature (New York: Peter Lang,1996)

- ^ Ibn Warraq, "Edward Said and the Saidists: or Third World Intellectual Terrorism", Secular Islam[dead link]

- ^ MacKenzie, J.M., 1995, Orientalism: history, theory and the arts, Manchester, Manchester University Press, page 11

- ^ MacKenzie, J.M., 1995, Orientalism: history, theory and the arts, Manchester, Manchester University Press

- ^ Dangerous Knowledge by Robert Irwin Martin Kramer reviewing Dangerous Knowledge.

- ^ a b Landow, George P. Political Discourse — Theories of Colonialism and Postcolonialism. Edward W. Said's Orientalism

- ^ Edward W. Said's on Orientalist Scholarship

- ^ Said, Edward."The Clash of Ignorance," The Nation October 22, 2001, accessed April 26, 2007.

- ^ a b Orientalism, pp. 317-8

- ^ Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid by Daniel Martin Varisco. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2007.

- ^ Defending the West: A Critique of Edward Said's Orientalism, Ibn Warraq (2007) ISBN 1-59102-484-6

Further reading

- Balagangadhara, S. N. "The Future of the Present: Thinking Through Orientalism", Cultural Dynamics, Vol. 10, No. 2, (1998), pp. 101–23. ISSN 0921-3740.

- Benjamin, Roger Orientalist Aethetics, Art, Colonialism and French North Africa: 1880-1930, U. of California Press, 2003

- Biddick, Kathleen. "Coming Out of Exile: Dante on the Orient(alism) Express", The American Historical Review, Vol. 105, No. 4. (Oct., 2000), pp. 1234–1249.

- Fleming, K.E. "Orientalism, the Balkans, and Balkan Historiography", The American Historical Review, Vol. 105, No. 4. (Oct., 2000), pp. 1218–1233.

- Halliday, Fred. "'Orientalism' and Its Critics", British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2. (1993), pp. 145–163.

- Irwin, Robert. For lust of knowing: The Orientalists and their enemies. London: Penguin/Allen Lane, 2006 (ISBN 0-7139-9415-0)

- Kabbani, Rana. Imperial Fictions: Europe's Myths of Orient. London: Pandora Press, 1994 (ISBN 0-04-440911-7).

- Kalmar, Ivan Davidson & Derek Penslar. Orientalism and the Jews Brandeis 2005

- Klein, Christina. Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945–1961. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003 (ISBN 0-520-22469-8; paperback, ISBN 0-520-23230-5).

- Knight, Nathaniel. "Grigor'ev in Orenburg, 1851–1862: Russian Orientalism in the Service of Empire?", Slavic Review, Vol. 59, No. 1. (Spring, 2000), pp. 74–100.

- Kontje, Todd. German Orientalisms. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 (ISBN 0-472-11392-5).

- Little, Douglas. American Orientalism: The United States and the Middle East Since 1945. (2nd ed. 2002 ISBN 1-86064-889-4).

- Lowe, Lisa. Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992 (ISBN 978-0-8014-8195-6).

- Macfie, Alexander Lyon. Orientalism. White Plains, NY: Longman, 2002 (ISBN 0-582-42386-4).

- MacKenzie, John. Orientalism: History, theory and the arts. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995 (ISBN 0-7190-4578-9).

- Murti, Kamakshi P. India: The Seductive and Seduced "Other" of German Orientalism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001 (ISBN 0-313-30857-8).

- Noble dreams, wicked pleasures: Orientalism in America, 1870–1930 by Holly Edwards (Editor). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000 (ISBN 0-691-05004-X).

- Orientalism and the Jews, edited by Ivan Davidson Kalmar and Derek Penslar. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2004 (ISBN 1-58465-411-2).

- Oueijan, Naji. The Progress of an Image: The east in English Literature. New York: Peter Lang Publishers, 1996.

- Peltre, Christine. Orientalism in Art. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group (Abbeville Press, Inc.), 1998 (ISBN 0-7892-0459-2).

- Prakash, Gyan. "Orientalism Now", History and Theory, Vol. 34, No. 3. (Oct., 1995), pp. 199–212.

- Rotter, Andrew J. "Saidism without Said: Orientalism and U.S. Diplomatic History", The American Historical Review, Vol. 105, No. 4. (Oct., 2000), pp. 1205–1217.

- Varisco, Daniel Martin. "Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid." Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007. (ISBN 978-0-295-98752-1).

External links

- Orientalism 25 Years Later, by Said in 2003

- An Introduction to Edward Said, Orientalism, and Postcolonial Literary Studies, by Amardeep Singh

- Said's Splash, by Martin Kramer, on the book's impact on Middle Eastern studies.

- Malcolm Kerr's review of the book.

- The Edward Said Archive, articles by and about Edward Said and his works.

- Encountering Islam, a critique of Said's Orientalism by Algis Valiunas, in the Claremont Review of Books.

- Review by William Grimes, of Grimes' "Dangerous Knowledge," [a critique of 'Orientalism'] in the New York Times, November 1, 2006.

Articles

- "China in Western Thought and Culture" Dictionary of the History of Ideas, etext, University of Virginia

- John E. Hill, translation, Hou Hanshu

- Brian Whitaker, "Distorting Desire", review, Joseph Abbad, Desiring Arabs, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, from Al-Bab.com, on Reflections of a Renegade blog site

- Iskandar, Adel (July 2003). "Whenever, Wherever! The Discourse of Orientalist Transnationalism in the Construction of Shakira". http://ambassadors.net/archives/issue14/selected_studies4.htm.

- Martin Kramer, "Edward Said's Splash", from his book, Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in America, Washington: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2001, pp. 27–43.

- Andre Gingrich, "Frontier Orientalism", Camp Catatonia blog

- "Edward Said and the Production of Knowledge", CitizenTrack

- "Orientalism as a tool of Colonialism", Citizen Track

Categories:- 1978 books

- Political books

- Books about the Middle East

- Postcolonial literature

- Sociology books

- Islam-related literature

- Works by Edward Said

- Books of literary criticism

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.