- North American English regional phonology

-

North American English regional phonology is the study of variations in the pronunciation of spoken English by the inhabitants of various parts of North America. North American English can be divided into several regional dialects based on phonological, phonetic, lexical, and some syntactic features. North American English includes American English, which has several highly developed and distinct regional varieties, along with the closely related Canadian English, which is more homogeneous. American English (especially Western dialects) and Canadian English have more in common with each other than with the many varieties of English outside North America.

The most recent work documenting and studying the phonology of North American English dialects as a whole is the Atlas of North American English by William Labov, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg, on which much of the description below is based, following on a tradition of sociolinguistics dating to the 1960s; earlier large-scale American dialectology focused more on lexical variation than on phonology.

Contents

Defining regions of North American speech

Regional dialects in North America are most strongly differentiated along the Eastern seaboard. The distinctive speech of important cultural centers like Boston, Massachusetts (see Boston accent); Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and New Orleans, Louisiana imposed their marks on the surrounding areas. The Connecticut River is usually regarded as the southern/western extent of New England speech, while the Potomac River generally divides a group of Northern coastal dialects from the beginning of the Coastal Southern dialect area (distinguished from the Highland Southern or South Midland dialect treated below, although outsiders often mistakenly believe that the speech in these two areas is the same); in between these two rivers several local variations exist, most famous among them the variety that prevails in New York City.

Dialects on the East Coast of the continent are most diverse chiefly because the East Coast has been populated by English-speaking people longer than any other region. Western speech is much more homogeneous because it was settled by English speakers more recently, and so there has been less time for the West to diversify into a multiplicity of distinctive accents. A reason for the differences between (on the one hand) Eastern and (on the other hand) Midwestern and Western accents is that the East Coast areas were in contact with England, and imitated prestigious varieties of British English at a time when those varieties were undergoing changes. The interior of the country was settled by people who were no longer closely connected to England, as they had no access to the ocean during a time when journeys to Britain were always by sea, and so Western and inland speakers did not imitate the changes in speech from England.

African American Vernacular English contains many distinctive forms that are more homogeneous from region to region than the accents of white speakers, but African-American speakers are subject to regional variation also.

General American

Main article: General AmericanGeneral American is a notional accent of American English perceived by Americans to be most "neutral" and free of regional characteristics. A General American accent is not a specific well-defined standardized accent in the way that Received Pronunciation (RP) has historically been the standard, prestigious variant of the English language in England; rather, accents with different features can all be perceived as General American provided they lack certain non-standard features.

One feature that General American is generally agreed to include is rhotic pronunciation, which maintains the coda [ɹ] in words like pearl, car, and court. Unlike RP, General American is characterized by the merger of the vowels of words like father and bother, flapping, and the reduction of vowel contrasts before historic /ɹ/. General American also has yod dropping after alveolar consonants.

The widespread Mary–marry–merry merger and the wine–whine merger are complete in most regions of North America and very common at least in informal and semi-formal varieties of others; however, the most formal varieties tend to be more conservative in preserving these phonemic distinctions. Other phonemic mergers present in some speakers in certain regions include the cot–caught merger and the pin–pen merger (a conditional merger).

One phenomenon apparently unique to American accents is the irregular behavior of words that in RP have /ɒrV/ (where V stands for any vowel). Words of this class include, among others: origin, Florida, horrible, quarrel, warren, borrow, tomorrow, sorry, and sorrow. In General American there is a split: the majority of these words have /ɔɹ/, but the last four words of the list above have /ɑɹ/. In the New York accent, through New Jersey and Philadelphia, and in the Carolinas, most or all of these words are pronounced /ɑɹ/ by many speakers (Shitara 1993). In Canadian English, however, all of the words in this class are pronounced /ɔɹ/.

The Midland

Main article: Midland American EnglishThe region of the Midwestern United States west of the Appalachian Mountains begins the broad zone of what is generally called "Midland" speech. In older and traditional dialectological research, this is divided into two discrete subdivisions: the "North Midland" that begins north of the Ohio River valley area and the "South Midland" dialect area. In more recent work such as the Atlas of North American English, the former is designated simply "Midland" and the latter is reckoned as part of the South. The (North) Midland is arguably the major region whose dialect most closely approximates "General American".

The North Midland and South Midland are both characterized by having a distinctly fronter realization of the /oʊ/ phoneme (as in boat) than many other American accents, particularly those of the North; the phoneme is frequently realized with a central nucleus, approximating [əʊ]. Likewise, /aʊ/ has a fronter nucleus than /aɪ/, approaching [æʊ]. Another feature distinguishing the Midland from the North is that the word on contains the phoneme /ɔ/ (as in caught) rather than /ɑ/ (as in cot). (Obviously this only applies to Midland speakers not subject to the cot–caught merger, on which see below.) For this reason, one of the names for the North-Midland boundary is the "'On' line".

In some areas of the Midland, words like "roof" and "root" (which in many other dialects have the vowel uː) are pronounced with the vowel of "book" and "hoof" ʊ.[citation needed]

A common non-phonological feature of the greater Midland area is so-called positive anymore: it has become possible to use the word anymore with the meaning 'nowadays' in sentences without negative polarity, such as Air travel is inconvenient anymore.

North Midland

The North Midland region stretches from east to west across central and southern Ohio, central Indiana, central Illinois, Iowa, and northern Missouri, as well as Nebraska and northern Kansas where it begins to blend into the West. Major cities of this dialect area include Columbus, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis. This area is currently undergoing a vowel merger of the "short o" /ɑ/ (as in cot) and 'aw' /ɔ/ (as in caught) phonemes. Many speakers show transitional forms of this so-called cot–caught merger, which is complete in approximately half of the rest of North America.

The /æ/ phoneme (as in cat) shows most commonly a so-called "continuous" distribution: /æ/ is raised and tensed toward [eə] before nasal consonants and remains low [æ] before voiceless stop consonants, and other allophones of /æ/ occupy a continuum of varying degrees of height between those two extremes.

South Midland

The South Midland dialect region follows the Ohio River in a generally southwesterly direction, moving across from Kentucky, southern Indiana, and southern Illinois to southern Missouri, Arkansas, southern Kansas, and Oklahoma, west of the Mississippi river. Although historically more closely related to the North Midland speech, this region shows dialectal features that are now more similar to the rest of the South than the Midland, most noticeably the smoothing of the diphthong /ɑɪ/ to [aː], and the second person plural pronoun "you-all" or "y'all." Unlike the coastal South, however, the South Midland has always been a rhotic dialect, pronouncing /r/ wherever it has historically occurred. South Indiana is the northernmost extent of the South Midland region, forming what dialectologists refer to as the "Hoosier Apex" of the South Midland; the accent is locally known there as the "Hoosier Twang".

The phonology of the South Midland is discussed in greater detail in the section on the South below.

St. Louis and vicinity

St. Louis, Missouri is historically one among several (North) Midland cities, but it has developed some unique features of its own distinguishing it from the rest of the Midland.

- A historical feature of the St. Louis dialect is the merger of the phonemes /ɔɹ/ (as in for) and /ɑɹ/ (as in far), while leaving distinct /oɹ/ (as in four). This merger is less frequently found in younger speakers, and leads to jokes referring to "I farty-far" and "Farest Park".[1]

- Some speakers, usually older generations, have /eɪ/ instead of Standard English /ɛ/ before /ʒ/: thus measure is pronounced /ˈmeɪʒ.ɚ/. Wash (as well as Washington) gains a /ɹ/, becoming /wɔɹʃ/ ("warsh").

- The diphthong /ɔɪ/ in standard English becomes more like [ɑːɪ]. For example, words such as "oil" and "joint" are commonly pronounced awyul and jawynt, particularly among older speakers within the city and immediate suburbs.[citation needed]

- The phoneme /ð/ is often replaced with /d/, especially among the white working-class urban populace. For instance, Get in that car over there sounds like Get in dat car over dere. This speech characteristic is common in most large, old cities of the East and Midwest, reinforcing St. Louis's cultural evolution alongside other northern industrial urban centers.[citation needed]

- Some younger speakers have picked up features of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, which is discussed in detail below in the section on the Inland North. This vowel shift causes, among other changes, raising and tensing of the vowel /æ/, so that words like cat /kæt/ to become more like [kɛət]. A corridor of communities between Chicago and St. Louis is the only place that features of the Inland North have penetrated noticeably into the Midland, despite the long boundary the two regions share. However, St. Louis remains a Midland city in other respects. For example on rhymes with dawn rather than don, unlike the North. Indeed, the fact that on rhymes with dawn is more distinctive in St. Louis than in the rest of the Midland, since the cot–caught merger is prevented in St. Louis by the presence of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift.

- Another feature typical of St. Louis speech is the ostensibly unique pronunciation of sundae as sunda /ˈsʌndə/. This does not carry over to any other words, not even Sunday. Again, this feature is less common in the speech of younger generations.[citation needed]

Western Pennsylvania

The dialect of Western Pennsylvania is, for many purposes, an eastern extension of the North Midland. Like the Midland proper, the Western Pennsylvania accent features fronting of /oʊ/ and /aʊ/, as well as positive anymore. The chief distinguishing feature of Western Pennsylvania as a whole is that the cot–caught merger is complete here, whereas it is still in progress in most of the Midland. The merger has also spread from Western Pennsylvania into adjacent West Virginia, historically in the South Midland dialect region.

The city of Pittsburgh is considered a dialect of its own often known as Pittsburghese. This region is additionally characterized by a sound change that is unique in North America: the monophthongization of /aʊ/ to [aː]. This is the source of the stereotypical Pittsburgh pronunciation of downtown as "dahntahn". Pittsburgh also features an unusually low allophone of /ʌ/ (as in cut); it approaches [ɑ] (/ɑ/ itself having moved out of the way and become a rounded vowel in its merger with /ɔ/).

The North

The dialect area of the United States north of Pennsylvania and the Midland is distinguished from the Midland by a collection of linguistic features whose isoglosses all largely coincide, despite not being directly structurally related to each other. Dialectologists in the first half of the 20th century distinguished the North from the Midland on the basis of a large collection of lexical isoglosses, mostly dealing with differences in agricultural terms that are now largely obsolete (such as the use of ko-day in the north versus sheepie in the Midland to call sheep from the pasture). Despite the obsolescence of these lexical differences, the boundary between the North and Midland is maintained in the same place by phonological and phonetic isoglosses.

- Where the Midland has fronting of /aʊ/ and /oʊ/, in the North the nucleus of /aʊ/ is further back than that of /aɪ/ and /oʊ/ remains a back vowel. Similarly, although /uː/ is fronted to the point of being a mid or front vowel in most of the United States and Canada, in the North the allophone of /uː/ after non-coronal consonants remains back. Indeed, in part of the north (much of Wisconsin and Minnesota), /uː/ remains back in all environments.

- Where the Midland has /ɔ/ (as in dawn) in on, the North has /ɑ/.

- Canadian raising of /aɪ/—i.e., the use of a raised allophone such as [ʌɪ] or [əɪ] for /aɪ/ before voiceless consonants—is very common in the North but infrequent in most of the Midland.

- There is no cot–caught merger in the North (as defined in the Atlas of North American English), although the merger is in progress in the Midland.

The North is also separated from the Midland by the presence of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift (NCVS), on which see below; although the NCVS is not found in all parts of the North, it is present in the part of the North most closely adjacent to the Midland and thus helps to define the boundary.

Inland North

Main article: Inland Northern American EnglishThe Inland North dialect region was once considered the "standard Midwestern" speech that was the basis for General American in the mid-20th century. However, it has been recently modified by the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, which is the main feature of this dialect region. Today the Inland North proper is regarded as the sub-region of the North where the NCVS predominates.

The Inland North is centered on the area south of the Great Lakes, and consists of two components: to the east, central and western New York State (including Syracuse, Binghamton, Rochester, and Buffalo); and to the west, much of Michigan's Lower Peninsula (Detroit, Grand Rapids), Toledo, Cleveland, Chicago, Gary, and Southeastern Wisconsin (Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha).

These two regions are separated by a region of northwestern Pennsylvania, including the city of Erie, which is not today part of the linguistic Inland North. Although Erie was historically part of the greater Northern dialect region, and is on the southern shore of Lake Erie halfway between Buffalo and Cleveland, it has not undergone the NCVS; instead, as a result of heavy influence from Pittsburgh, the cot–caught merger has taken place in Erie.

This map shows the approximate extent of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, and thus the approximate area where the Inland North dialect predominates. Note that the region surrounding Erie, Pennsylvania is excluded.

This map shows the approximate extent of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, and thus the approximate area where the Inland North dialect predominates. Note that the region surrounding Erie, Pennsylvania is excluded.

The NCVS is not uniform throughout the Inland North; it is most advanced in Western New York and Michigan, and less developed in Cleveland. At the eastern fringes are areas in which most speakers display NCVS features only in weak forms if at all, including northeastern Pennsylvania and some communities in northern and eastern New York. Northern Indiana and part of Minnesota show the first stage of the NCVS, tensing of /æ/, without any of the other stages.

The Northern Cities Vowel Shift

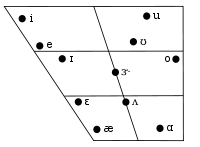

Main article: Northern Cities Vowel ShiftThe NCVS is a chain shift involving movements of six vowel phonemes:

- The first stage of the shift is the raising, tensing, and diphthongization of /æ/ towards [ɪə]. This results in words like "cat" being pronounced more like "kyat." This change occurs for the phoneme /æ/ in all contexts, in contrast with other American dialects in which phonetically similar "æ-tensing" occurs only before nasal consonants, or as part of a phonemic split of /æ/ into two phonemes, one tensed and the other still lax.

- The second stage is the fronting of /ɑ/ to [aː]. In some speakers this fronting is so extreme that their /ɑ/ phoneme can be mistaken for /æ/ by speakers of other dialects; thus for example block approaches the way other dialects pronounce black.

- In the third stage, /ɔ/ lowers towards [ɑ], causing stalk to sound more like other dialects' stock. The lowering of the phoneme /ɔ/ is not unique to this region. However, in other regions where such a lowering occurs, it results in the cot–caught merger. The merger does not occur in the Inland North because NCVS speakers front the /ɑ/ phoneme to [a], thus maintaining the distinction between /ɑ/ and /ɔ/.

- The fourth stage is the backing and sometimes lowering of /ɛ/, toward either [ə] or [æ].

- In the fifth stage, /ʌ/ is backed towards [ɔ], so that stuck sounds like stalk in dialects that maintain a [ɔ] sound in the word stalk. In this regard, a sound change occurs in the Inland North that is the reverse of most other American dialects (including the Midland): /ʌ/ is backer than /ɑ/ rather than fronter.

- In the sixth stage, /ɪ/ is lowered and backed. However, it is kept distinct from [ɛ] in all contexts, so, the pin–pen merger does not occur.

This shift is in progress across the region, though not necessarily completed. So, any individual speaker may display some of these six shifts without displaying the others. On the whole, though, the shifts occur in the order listed above, so speakers who display advanced forms of the later changes will generally be advanced in the earlier changes as well.

North Central

Main article: North Central American EnglishThe North Central dialect region extends from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan westward across northern Minnesota and North Dakota and into eastern Montana. Although the Atlas of North American English does not include the North Central region as part of the North proper, it shares all of the features listed above as properties of the North as a whole. The North Central is a linguistically conservative region; it participates in few of the major ongoing sound changes of North American English.

The movie Fargo, which takes place in the North Central region, famously features an exaggerated version of this accent.[citation needed]

- Unlike most of the rest of the North, the cot–caught merger is prevalent in the North Central region.

- The North Central region is stereotypically associated with a "sing-songy" intonation which is said to derive from the pitch accent pattern of the Scandinavian languages, speakers of which were among the largest immigrant groups to this area during its early settlement. In urban Minnesota, this variation of NCAE is referred to as "Minnewegian," a portmanteau of Minnesota and Norwegian.[citation needed]

- Older speakers in the region may merge /w/ and /v/, making well sound like "vell".[citation needed]

- Older and rural speakers may also merge /ð/ into /d/ and /θ/ into /t/.[citation needed] This feature and the foregoing one are again associated with the Scandinavian linguistic substratum, in that most Scandinavian languages do not possess /w/, /ð/, or /θ/ phonemes.

Western New England

Western New England, encompassing most of Connecticut, western Massachusetts, and Vermont, has close historical ties to the Inland North: it is from Western New England that the westward migration began that led to the settlement of most upstate New York and the rest of the Inland North. The linguistic boundary between Western and Eastern New England has been recognized at least since the 1940s; Western New England differed from Eastern New England then in being rhotic, possessing the Mary–marry–merry merger, and not being subject to the caught–cot merger, among other features. Historically, Western New England is distinguished from Eastern New England in that it consists principally of communities settled from the Connecticut and New Haven colonies, rather than the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies.

Today, Western New England shares in the principal linguistic features listed above as characteristic of the North. Connecticut and western Massachusetts in particular show the same general phonological system as the Inland North, and some speakers show a general tendency in the direction of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift—for instance, an /æ/ that is somewhat higher and tenser than average, an /ɑ/ that is fronter than /ʌ/, and so on. The caught–cot merger has taken hold comparatively recently in Vermont, merging to an unrounded vowel [a] (unlike in Eastern New England, where the merged cot-caught vowel is back and rounded). In Connecticut /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ remain distinct, although the merger shows some evidence of being in progress advancing southward from Vermont.

Northeastern dialects

Most of the major cities of the Northeast Megalopolis have distinctive accents that cover smaller regions than the broad "North" and "Midland" categories of the Midwest, reflecting the greater dialect diversity of the Northeast. These dialects are not all closely related to each other, but subsets of them share several unusual features, such as non-rhoticity or a split of /æ/ into two separate phonemes.

One feature shared by all of them is resistance to the Mary–marry–merry merger. Similarly, these dialects retain a distinction between historical short o and long o before intervocalic /ɹ/, so that, for example, orange, Florida, and horrible have a different stressed vowel than story and chorus.

Eastern New England

Main article: Boston accentThe Eastern New England dialect area encompasses Maine, New Hampshire, and eastern Massachusetts (including Greater Boston). The dialect spoken here shares features with the greater North dialect region, including Canadian raising of /aɪ/ and minimal fronting of /aʊ/ and /oʊ/, but it possesses enough distinctive features of its own to distinguish it from the North as a separate dialect system. Southern New Hampshire has been reported as retreating from some of the more distinctive features of the Eastern New England dialect region.

This region of the United States historically had more contact with British varieties of English (being nearer to the Atlantic coast) and looked to England as a standard of prestige for their speech. Hence, the Eastern New England dialect has in some respects more similarities with British English than many other dialects of American English have. Most famously, Eastern New England accents (with the exception of Martha's Vineyard) are traditionally non-rhotic.

The Eastern New England accent is seemingly unique in North America for not having undergone the so-called father–bother merger: in other words, the stressed vowel phonemes of father and bother remain distinct as /aː/ and /ɒː/, so that the two words do not rhyme as they do in most American accents. Many Eastern New England speakers also have a class of words with "broad A"—that is, /aː/ as in father in words that in most accents contain /æ/, such as bath, half, and can't. Broad A is another feature that Eastern New England shares with southern England. On the other hand, unlike dialects of England, the Eastern New England dialect is subject to the cot–caught merger, merging the cot and caught classes to a back rounded vowel, [ɒː].

As mentioned above, Eastern New England retains the distinction between the vowel phonemes of marry, merry, and Mary. Likewise, many Eastern New England speakers preserve the distinctions between /iː/ and /ɪ/ before intervocalic /ɹ/ (as in nearer and mirror), as well as the distinction between /ʌ/ and /ɝ/ before intervocalic /ɹ/ (as in hurry and furry).[citation needed]

The distinction between the vowels of horse and hoarse is maintained in traditional non-rhotic New England accents as [hɒːs] for horse (with the same vowel as cot and caught) vs. [hoəs] for hoarse. Thus, the horse–hoarse merger does not occur. Like some other east-coast accents as well as AAVE, some accents of eastern New England merge /oɹ/ and /uɹ/, making homophones of pairs like pour/poor, more/moor, tore/tour, cores/Coors etc.[citation needed] Eastern New England has a so-called nasal short-a system. In other words, the /æ/ phoneme has highly distinct allophones before nasal consonants.

Rhode Island

Rhode Island is traditionally grouped with the Eastern New England dialect region, both by the dialectologists of the mid–20th century and by the Atlas of North American English; it shares Eastern New England's traditional non-rhoticity and nasal short-a system. A key linguistic difference between Rhode Island and the rest of the Eastern New England, however, is that Rhode Island is subject to the father–bother merger and not the cot–caught merger. Indeed, Rhode Island shares with New York and Philadelphia an unusually high and back allophone of /ɔ/ (as in caught), even compared to other communities that do not have the cot–caught merger.

In the Atlas of North American English, the city of Providence (the only community in Rhode Island sampled by the Atlas) is also distinguished by having the backest realizations of /uː/, /oʊ/, and /aʊ/ in North America.

New York City

Main article: New York dialectAs in Eastern New England, the accents of New York City and adjoining New Jersey cities are traditionally non-rhotic. The vowels of cot /kɑt/ and caught /kɔt/ are distinct; in fact the New York dialect has the highest realizations of /ɔ/ in North American English, approaching [oə] or even [ʊə]. The vowel of cart is back and rounded [kɒːt] instead of fronted as it is in Boston.

The accent is well attested in American movies and television shows, especially ones about American mobsters. It is often referred to more narrowly as the "Bronx" or "Brooklyn accent", although in fact research has found no variation between the different boroughs of New York per se. Bugs Bunny and Groucho Marx both speak with a Brooklyn accent in their films. The accent is often exaggerated, but nevertheless still exists to some degree among Brooklyn natives. The English used in the popular television show The Sopranos, set in Essex County, New Jersey, is often more close to a Brooklyn accent, than that of New Jersey, mainly regarding the rhotic feature. Furthermore, the dialect portrayed on this television show does not apply to citizens of the entire state; it is a particular socio-ethnic accent.

New Jersey

Main article: New Jersey EnglishPennsylvania

Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley

Main article: Philadelphia accentThe accent of Philadelphia and nearby parts of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, is probably the original ancestor of General American. It is one of the few coastal accents that is rhotic, and one of the first to merge the historical /or/ of hoarse, mourning with the /ɔr/ of horse, morning. It also maintains the cot–caught contrast, unlike New England and western Pennsylvania. Nevertheless there are differences between modern Philadelphia speech and General American, some of which, as described in Labov, Ash, & Boberg (2006) and Labov (2001), will be outlined here.

- "Water" is sometimes pronounced [wʊɾər], that is, with the vowel of wood

- As in New York City, but unlike General American, words like orange, horrible, etc., are pronounced with /ɑr/. See English-language vowel changes before historic r: "Historic 'short o' before intervocalic r".

- On is pronounced /ɔn/, so that, as in the South and Midland (and unlike New York and the North) it rhymes with dawn rather than don.

- The /oʊ/ of goat and boat is fronted, so it is pronounced [əʊ], as in the Midland and South.

- The phoneme /æ/ undergoes tensing in some words. Fewer words have the tense variant in Philadelphia than in New York City; for instance, mad and sad have different vowels.

- As in New York City and Boston, there is a three-way distinction between Mary, marry, and merry. A recent development is a merger of the vowel of merry with Murray.

- Canadian raising occurs for /aɪ/ (price) but not for /aʊ/ (mouth)

- There is a split of /eɪ/ (face) so at the end of a word (for example, day) it is a wide diphthong similar to that of Australian English, while in any other position (for example, date) it is very narrow and resembles /i/. Commonly confused words include eight and eat, snake and sneak, slave and sleeve.

Other parts of Pennsylvania

See also: Pittsburgh dialect, Central Pennsylvania accent, Northeast Pennsylvania English, and Pennsylvania Dutch EnglishBaltimore, Maryland

Main article: Baltimore dialectSouthern American English

Main article: Southern American EnglishFew generalizations can be made about Southern pronunciation as a whole, as there is great variation between regions in the South (see different southern American English dialects for more information) and between older and younger people. Upheavals such as the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl and World War II have caused mass migrations throughout the United States. Southern American English as we know it today began to take its current shape only after World War II. Some generalizations include:

- The conditional merger of [ɛ] and [ɪ] before nasal consonants, the pin–pen merger.

- The diphthong /aɪ/ becomes monophthongized to /aː/.

- Lax and tense vowels often merge before /l/

The South Midland dialect follows the Ohio River in a generally southwesterly direction, moves across Arkansas and Oklahoma west of the Mississippi, and peters out in West Texas. It is a version of the Midland speech that has assimilated some coastal Southern forms, most noticeably the loss of the diphthong [ɑɪ], , which becomes [ɑː], and the second person plural pronoun "you-all" or "y'all."

South Midlands speech is characterized by:

- monophthongization of [ai] as [aː], for example, most dialects' "I" → "Ah" in the South.

- raising of initial vowel of [au] to [æu]; the initial vowel is often lengthened and prolonged, yielding [æːw].

- nasalization of vowels, esp. diphthongs, before [n].

- raising of [æ] to [e]; can't → cain't, etc.

- Unlike most American English, but like British English, glides ([j], the y sound) are inserted before [u] after the consonants [t], [d], [θ], [s], [z], [n], and [l]; that is to say, yod dropping does not occur.

- South Midlands speech is rhotic. This is the principal feature that distinguishes South Midland speech from the non-rhotic coastal Southern varieties.

Southern Drawl

The Southern Drawl, or the diphthongization/triphthongization of the traditional short front vowels as in the words pat, pet, and pit: these develop a glide up from their original starting position to [j], and then in some cases back down to schwa.

- /æ/ → [æjə]

- /ɛ/ → [ɛjə]

- /ɪ/ → [ɪjə]

Southern vowel shift

- [ɪ] moves to become a high front vowel, and [ɛ] to become a mid front unrounded vowel. In a parallel shift, the /i/ and /e/ relax and become less front.

- The back vowels /u/ in "boon" and /o/ in "code" shift considerably forward.

- The open back unrounded vowel /ɑr/ "card" shifts upward towards /ɔ/ "board", which in turn moves up towards the old location of /u/ in "boon". This particular shift probably does not occur for speakers with the cot–caught merger.

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina has a very distinctive southern accent that encompasses elements of standard British English and American Southern English, with additional French-Huguenot influences. However, given Charleston's high concentration of African-Americans that spoke the Gullah language, the speech patterns were more influenced by the dialect of the Gullah African-American community. The most distinguishing feature of this accent is the way speakers pronounce the name of the city, to which a standard listener would hear "Chahls-ton", with a silent r. Alone among the various regional Southern dialects, Charlestonian speakers inglide long mid vowels, such as the raising for /aj/ and /aw/. Some attribute these unique features of Charleston's speech to its early settlement by the French Huguenots and Sephardi Jews, both of which played influential parts in Charleston's development and history.

New Orleans

Parallels include the split of the historic short-a class into tense [eə] and lax [æ] versions, as well as pronunciation of cot and caught as [kɑt] and [kɔt]. The stereotypical New York curl–coil merger of "toity-toid street" (33rd Street) used to be a common New Orleans feature, though it has mostly receded today.

Perhaps the most distinctive New Orleans accent is locally nicknamed "yat", from a traditional greeting "Where y'at" ("Where are you at?", meaning "How are you?"). One of the most detailed phonetic depictions of an extreme "yat" accent of the early 20th century is found in the speech of the character Krazy Kat in the comic strip of the same name by George Herriman. While such extreme "yat" accents are no longer so common in the city, they can still be found in parts of Mid-City and the 9th ward, as well as in St. Bernard Parish, just east of New Orleans.

The novel A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole is generally considered the best depiction of New Orleans accents in literature.

Acadiana

English speakers in this specific region of southwest Louisiana (also referred to as Cajun country) have carried over many words and phrases from the colonial French (i.e. Newfoundland, Nova Scotia) because of the eviction and resettlement of early French colonials by the British. A number of people in this area speak a variety of Cajun French, although the number has been declining in recent years.

Miami accent

In Miami, a unique accent, commonly called the "Miami accent", is widely spoken. It developed mostly by second- or third-generation Hispanics whose first language was English. It contains a rhythm and pronunciation heavily influenced by Spanish.[2]

Western Dialect

The Western United States is the largest dialect region in the United States, and the one with the fewest distinctive phonological features. These facts can both be attributed to the fact that the West is the region most recently settled by English speakers, and so there has not been sufficient time for the region either to develop highly distinctive innovations or to split into strongly distinct dialectological subregions. There is some evidence, though, that some regions of the West are beginning to diverge from each other linguistically.[citation needed]

California English

Main article: California EnglishThere are several phonological processes which have been identified as being particular to California English. However, these shifts are by no means universal in Californian speech, and any single Californian's speech may have only some of the changes identified below, or even none of them. Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon often demonstrate this Californian shift. California English possesses a new chain vowel shift known as the California vowel shift:

The California vowel shift, based on a diagram at Penelope Eckert's webpage.

The California vowel shift, based on a diagram at Penelope Eckert's webpage.

- Before /ŋ/, /ɪ/ is raised to [i], so "king" has the same vowel of "keen" rather than "kin".[3]

- /æ/ is raised and diphthongized to [eə] or [ɪə] before nasal consonants. So "ban" is pronounced "bay-uhn".

- before /ŋ/ it may be identified with the phoneme /e/, so "thank" is pronounced "thaynk".

- Elsewhere /æ/ is lowered in the direction of [a], so "cat" sounds closer to "caht".

- /ʊ/ is moving towards [ʌ], so "put" sounds more like "putt".

- /ʌ/ towards [ɛ], so "putt" can sound slightly similar to "pet".

- /ɛ/ toward [æ], so "kettle" sounds like "cattle".

- /ɑ/ toward [ɔ]: "cot" and "caught" are moving closer to General American "caught".

- The vowels /uː/ ("blue") and /oʊ/ ("mope") are pronounced closer to the front of the mouth.

California English also possesses the following features:

- Traditionally diphthongal vowels such as [oʊ] as in boat and [eɪ], as in bait, have acquired qualities much closer to monophthongs.

- A notable exception to the cot–caught merger may be found within the city limits of San Francisco, especially by older speakers.

- The pin–pen merger is complete in Bakersfield, and speakers in Sacramento either perceive or produce the pairs /ɛn/ and /ɪn/ close to each other.[4]

Pacific Northwest English

Main article: Pacific Northwest EnglishPacific Northwest English is fairly similar to other areas of the West. It possesses features shared in common with California English and West/Central Canadian English, depending on the region. The accent of Southern Oregon shares several features of California English (such as the California vowel shift) , and Northern Washington has some features similar to West/Central Canadian English such as the Canadian Shift.[citation needed]

- [ɛ] as [eɪ] before /ɡ/, and [æ] as [eɪ] before /ɡ/ and /ŋ/: "leg" and "lag" pronounced [leɪɡ]; "tang" pronounced [teɪŋ].

- Further diphthongization of [ɛ] as [ɛɪ]: "egg" and "leg" are pronounced "ayg" and "layg".

- The Pacific Northwest also has some of the features of the California vowel shift and the Canadian vowel shift:

- /æ/ is raised and diphthongized to [eə] before nasals by some speakers.

- /æ/ is lowered in the direction of [a] by some.[citation needed]

- Other features of the California vowel shift are mostly found in Southern Oregon.

Canadian English

Main article: Canadian EnglishCanadian English (CanE) is the variety of North American English used in Canada. The phonetics and phonology for most of Canada are very similar to that of the Western and Midlands regions of the United States. Canada has relatively less dialectal diversity compared to the United States and other English-speaking countries.

West/Central Canadian English

Main article: West/Central Canadian EnglishThe most common variety of Canadian English the one spoken in West/Central Canada. Overall, the pronunciation of English in most of Canada, and especially in Central and Western Canada, is very similar to the pronunciation of English found in the Western United States; Canadian raising and the Canadian vowel shift are the most distinctive features.

Canadian raising

Main article: Canadian raisingA number of Canadians have a distinct feature called "Canadian raising" (Chambers 1973). This feature means that the nucleus of the diphthongs /aɪ/ and /aʊ/ are "raised" before voiceless consonants. In most varieties of American English pairs such as pouter/powder and rider/writer are pronounced exactly the same. In Canadian English, however, when a diphthong is followed by the voiceless consonants such as /p/ /t/ /k/ /f/ and some others, the starting point of the diphthong raises from an open central vowel to a mid one.

For example, ride is pronounced [raɪd] but with write, because the diphthong is followed by a /t/, the diphthong raises and the word is pronounced [rəɪt]. Most other speakers of American English do not possess these allophonic sounds ([əʊ] and [əɪ]) but the pronunciation is still marked. The Canadian pronunciation of "about the house" may sound like "a boat the hoas" to speakers of dialects without the raising, and in many cases is misheard (or deliberately exaggerated) as "aboot the hoos". Some stand-up and situation comedians, as well as television shows (such as South Park) exaggerate the pronunciation to *"aboot the hoos" for comic effect. True Canadian raising affects both /aʊ/ and /aɪ/, but a related phenomenon, of much wider distribution throughout the United States, affects only /aɪ/. So, whereas the General American pronunciations of rider and writer are identical ([ɹaɪɾɚ]), those American English speakers whose dialects include either the full or restricted Canadian raising will pronounce them as [ɹaɪɾɚ] and [ɹəɪɾɚ], respectively. Canadian raising is quite strong in most of Ontario and the Maritimes as well as in the Prairies. It is receding in British Columbia, and many of these speakers do not raise /aɪ/ before voiceless consonants. Younger speakers in the Lower Mainland do not even raise /aʊ/.[citation needed]

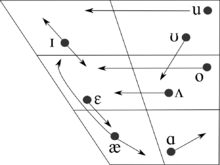

Canadian Vowel Shift

Main article: Canadian ShiftThe cot–caught merger creates a hole in the short vowel sub-system[5] and triggers a sound change known as the Canadian Shift, mainly found in Ontario, English-speaking Montreal and further west, and led by Ontarians and women; it involves the front lax vowels /æ/, /ɛ/, /ɪ/. It is also found scattered throughout the Western United States.

The vowels in the words cot and caught merge to [ɒ], a low back rounded vowel. The /æ/ of bat is retracted to [a] (except before nasals). Indeed, /æ/ is lower in this variety than almost all other North American dialects;[6] the retraction of /æ/ was independently observed in Vancouver[7] and is more advanced for Ontarians and women than for people from the Prairies or Atlantic Canada and men.[8] Then, /ɛ/ and /ɪ/ are lowered in the direction of [æ] and [ɛ] and/or retracted; studies actually disagree on the trajectory of the shift.[9]

References

Bibliography

- Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. p. 68. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- Shitara, Yuko (1993). "A survey of American pronunciation preferences". Speech Hearing and Language 7: 201–32.

- Mencken, H. L. (1936, repr. 1977). The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States (4th edition). New York: Knopf.

- Rainey, Virginia, (2004) Insiders' Guide: Salt Lake City (4th ed.), The Globe Pequot Press, ISBN 0-7627-2836-1

- Brigham Young University Linguistics Department Research Teams

- BYU "Utah English" Research Team's Homepage

- "How We Talk: American Regional English Today" by Allan A. Metcalf, 2000, Houghton Mifflin.

- "Utahnics", segment on All Things Considered, National Public Radio February 16, 1997.

- Chambers, J. K. "Canadian raising". Canadian Journal of Linguistics 18.2 (1973): 113–35.

- Dailey-O'Cain, J. "Canadian raising in a midwestern U.S. city". Language Variation and Change 9,1 (1997): 107-120.

- Labov, W. "The social motivation of a sound change". Word 19 (1963): 273–309.

- Labov, William (2001). Principles of Linguistic Change: Social Factors. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17916-X.

- Wells, J. C. Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- McCarthy, John (1993). A case of surface constraint violation. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 38. 169–95.

- Metcalf, Allan (2000), How We Talk, Houghton Mifflin, Boston.

- George Mason University. The Speech Accent Archive, 22 September 2004.

- Walsh M: Vermont Accent: Endangered Species? Burlington Free Press February 28, 1995

- Walt Wolfram and Ben Ward, editors (2006). American Voices: How Dialects Differ from Coast to Coast. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Footnotes

- ^ Wolfram and Ward, p. 128.

- ^ `Miami Accent' Takes Speakers By Surprise - Sun Sentinel

- ^ Penny Eckert, California vowels. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- ^ Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter. p. 68. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- ^ Martinet, Andre 1955. Economie des changements phonetiques. Berne: Francke.

- ^ Labov p. 219.

- ^ Esling, John H. and Henry J. Warkentyne (1993). "Retracting of /æ/ in Vancouver English."

- ^ Charles Boberg, "Sounding Canadian from Coast to Coast: Regional accents in Canadian English."

- ^ Labov et al. 2006; Charles Boberg, "The Canadian Shift in Montreal"; Robert Hagiwara. "Vowel production in Winnipeg"; Rebecca V. Roeder and Lidia Jarmasz. "The Canadian Shift in Toronto."

See also

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.